Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee (CINARC)

BUSINESS & BUSINESSMEN 商业

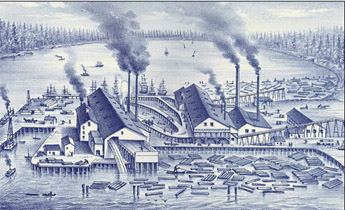

For decades, the San Francisco-based Alaska Packers Association operated more canneries (see the map on the

labor page) and produced more cans of salmon than any other company in the world.

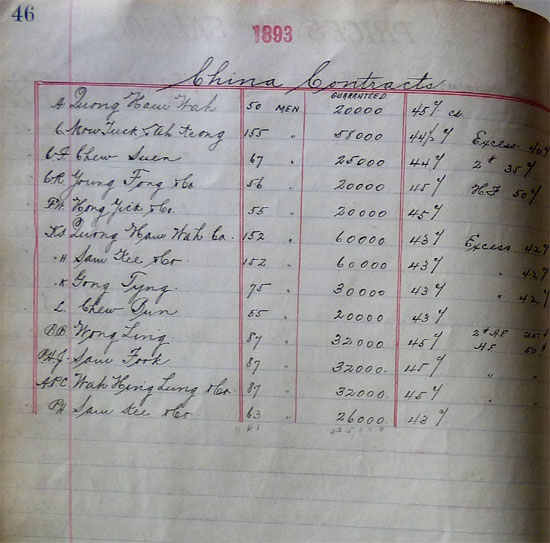

During the period 1892-1908, the APA worked with a total of 46 Chinese contractors to recruit workers for its canneries. Some only lasted a year or two but others enjoyed stable long-term relationships with the APA which could last a decade or more.

Who were those 46 Chinese contractors? Since the APA’s headquarter were in San Francisco, naturally their contractors were based in that city. A few were Portland-based. A couple could have been in Seattle or Astoria, OR.

Among them, Quong Ham Wah & Co in San Francisco was the most frequent contractor; it did not miss a single year. On Hing & Co. 安兴 of Portland, specializing in the Puget Sound canneries, was another regular after 1895. Chew Bun of San Francisco may have had an especially close relationship with the APA. When he died in 1903, his partner, Ah Ho, carried on the contract business with the Association. Like Chew Bun, Mow Tuck & Co began working with the APA as a contractor from the very beginning and did not end its relationship until 1903.

A Chinese contractor with the un-Chinese name of John Quinn contracting business as a separate company in the first years of APA business. After that he worked in partnership with Kwong Ying Kee & Co, Low Soon, and Lee Yuen.

It should be mentioned that the two decades discussed here saw two major innovations that affected the number of Chinese workers at each cannery. The first was the adoption at all APA canneries in or about 1904 of the so-called "Iron Chink" salmon butchering machine, which greatly reduced the demand for a highly paid group of workers. The second was the listing of Japanese workers and Japanese labor contractors after 1905. Filipinos must have joined the APA work force by then, but were probably listed as "other" ethnic groups.

Cannery Contractors for the APA, 1892-1908. 亚拉斯加罐头鱼业华工头

Becoming a contractor for Chinese labor must have been the ambition of many Chinese immigrants. That was where the big money was. Most Chinese who became truly wealthy in North America before the 1950s acquired much of their wealth through labor contracting: by hiring Chinese laborers and arranging with (usually) white employers for those laborers to do a set amount of work for a fixed sum of money, the wages and board of individual laborers to be paid by the contractor rather than the employer.

A similar system is quite common at present among employers who need work done but wish to avoid the complications of paying workers' benefits. In the past, when certain groups of laborers -- for instance, Chinese -- were competent, motivated, but not able to find work on their own, labor contracting was an obvious solution. Most railroads that used Chinese laborers used the contracting system. So did developers of canals in mining districts and farmers wishing to drain fields in flooded delta areas.

But of all labor contracting situations, that involving canneries may have been the most prevalent and profitable. Demand for workers was stable but seasonal. The tasks involved required some workers with experience and many without. Those tasks were unpleasant enough that most white Americans refused to do them. Contracting for Asian laborers, first Chinese and then Japanese and Filipinos, was a natural solution.

Relations between contractors and cannery owners or "packers" on the one hand and between laborers and contractors on the other, were complex. There was much exploitation and some outright oppression. On the other hand, workers often formed friendly relations with contractors, and it was almost essential for an aspiring contractor to be able to work smoothly with cannery owners, especially if he hoped to continue working with the same owners year after year.

For labor perspectives on railroad work, click here. For labor perspectives on canneries, click here.

Labor Contractors 包工头

Ah Gow and Ah Sing.

Ah Ho (San Francisco).

Chang Gow.

Chew Bun 赵柄枢 (San Francisco).

Chew Suen.

Chew Suen and John How.

Chin Quong (San Francisco).

Chin Quong and Ah Gow.

Chong Yick & Co. 昌益?/双益? (San Francisco).

Fook Sang Lung & Co.

Gong Tyng (San Francisco).

Him Yick Lung & Co.

Hong Fok Tong 同福堂 (Portland).

Hong Tong Chew & John How.

Hong Yick & Co. 恒益/同益 (with Chew Chew,

Chew Fung, Chew Mock)(Astoria)

Hop Wo Lung & Co.合和隆 (with Low Dong) (San

Francisco, Portland).

Hop Yik & Co 合益? (San Francisco).

John How and Ham Fon.

John Quinn & Co. (San Francisco)

Kwong Chong Lung & Co. 广昌隆(with Cn Lung?,

Chin Oy) (Portland),

Kwong Chun Yuen & Co 广春源 (San Francisco).

Kwong Lun Tai & Co. 广联泰 (Portland).

Kwong On Lung & Co. 广安隆 (Victoria BC and

San Francisco).

Kwong Ying Kee (same company as Quong Ying Kee?)

(with John Quinn). (San Francisco)

Lee Young.

Low Soon and John Quinn (San Francisco).

Low Yuen and Low Dong.

Mow Tuck & Co (with Ah Keong/Ah Kong)(San Francisco).

On Hing & Co 安兴 (with Chin Wing)(Portland)

Oy Wo Lung Sing Kee & Co. 会和隆 (San Francisco).

Pak Sing.

Quan Shing Lung & Co. 均盛隆 (with Lee You Ng) (San

Francisco)

Quong Chun Yuen & Co. (same as Kwong Chun Yuen?)

Quong Fat & Co. 广发 (San Francisco? Seattle?)

Quong Ham Wah & Co. 广谦和 (San Francisco).

Quong Mow Lung & Co. 广茂隆 (San Francisco).

Quong Tai Jan .

Quong Ying Kee 广英记 (with Yuen Lee, John Quinn)

(San Francisco).

Sam Fook.

Sam Kee & Co. 三记 ( Astoria)

or 森记 (Victoria BC?)

Tuck Lung Ching & Co.

Wah Hing Lung 华兴隆(San Francisco).

Wing Chong Wo & Co. 永昌和( San Francisco).

Wing Lun On & Co. 永联安 (San Francisco).

Wing On Wo & Co. 永安和(San Francisco).

Wing Sang Chung & Co.

Wong Ling.

Woo On Hai & Co..

Young Fong & Co.

Geo Aoki & Co. (with Geo Masui).

Komada & Co. (with Geo Tanaka, K Sadama & G.

Curtow)

References: International Chinese Directory, 1901.; Chung Sai Yat Po, March 21, 1902.

Merchants as Contractors 华人商家兼职工头

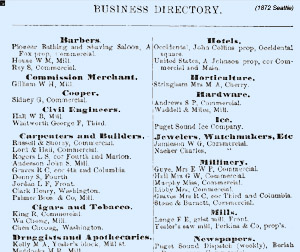

Most labor contractors did not advertise in print, either in English or Chinese. Presumably this was because their clients already knew them and because they recruited their laborers through posters on Chinatown walls or by word of mouth. Many also did business as merchants, however. In that role, they showed as much awareness of the value of advertising in newspapers and directories as did their white competitors.

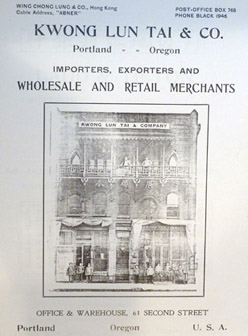

Kwong Lun Tai & Co 广联泰 was a contractor in Portland for the Alaska Packers Association between 1901 and 1904, for canneries at Ugashek and Nushagak in Alaska and at Anacortes in Washington. Kwong Lun Tai probably hired 100 to 300 workers for each of the Alaskan canneries. It is not clear how many were hired to work at Anacortes, which in 1904 was a new cannery site for the APA. Based in Portland, Kwong Lun Tai occupied two adjacent buildings for its office and warehouse, and was located on Second Street. It advertised itself as an importer and exporter as well as a wholesaler and retailer of general merchandise. In Kwong Lun Tai's full-page advertisement in a 1901 business directory, there is no mention of its being a labor contractor..

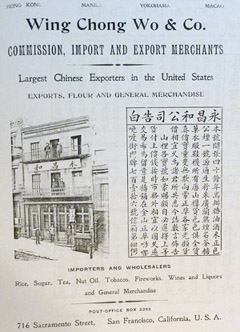

Another contractor was Wing Chong Wo & Co. 永昌和 of San Francisco. The company was new to the APA, active only in 1901 when it provided 105 Chinese workers for Ugashek. Based in a 3-story building on Sacramento Street, the heart of San Francisco's Chinatown, it had sold a variety of foodstuffs since 1860s. In a one-page advertisement in the 1901 business directory (left), it did not mention the labor contracting business. It describes itself as follows

“Our company has been in business for more than 4 decades, specializing in sugar, oil, alcohol, authentic licensed opium, top quality yuan-tong flower, tobacco from Zhu-guang-lan, well-reputed teas, candies, clothing, shoes, socks – all kinds of goods from China that we have gathered. The prices are not inflated and we treat children and seniors in the same honest way. It has long been known among our customers that we have maintained good business in San Francisco for good prices and quality. We have now more announcements: Companies in the interior who want to buy goods from us will receive the best quality but pay at lower than the advertised market price. This is our interest to build up a long-term business exchange. We pray to have your attention about this.”

Wing On Wo & Co. 永安和 was yet another similarly low-key labor contractor in San Francisco. The company too worked for APA for only one year in 1903, hiring 102 workers for a cannery at Cooks Inlet. Wing On Wo did the same kind of business as its competitor Wing Chong Wo and additionally provided banking and mailing services for immigrants from Taishan county. A business partner in Hong Kong helped to facilitate international remittances. Apparently Wing On Wo was run by men with the family name of Louie [Lei in pinyin], whose home town was in Taishan county. Lei Jia-he 雷家和 and Lei Jia-an 雷家安 were two of the key owner-managers at Wing On Wo.

Kwong Lun Tai advertisement, 1901

Wing Chong Wo

advertisement, 1901

Wing On Wo advertisement, 1903

References

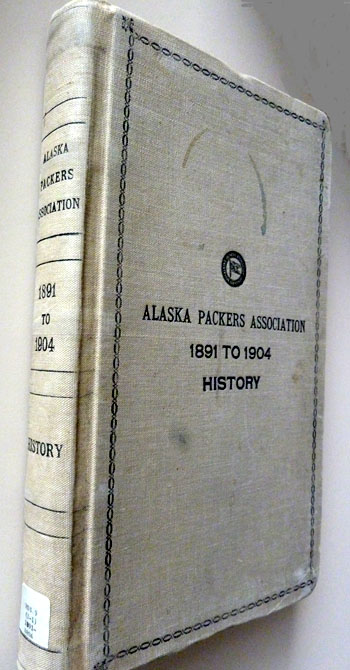

- Alaska Packers Association 1891-1904 History. Alaska State Library (Historical Collections), Juneau.

- Robert N. Nash, "The 'China Gangs' in the Alaska Packers Association Canneries, 1892-1935" , in The Life, Influence and the Role of the Chinese in the United Sates, 1776-1960, Chinese Historical Society of America, 1976, pp. 257-283.

- Thomas W. Chinn, "Chin Quong, Contractor," in Bridging the Pacific, San Francisco Chinatown and Its People, Chinese Historical Society of America, 1989, pp.80-84.

In 1893 thirteen Chinese contractors were listed in the handwritten APA "History" ledger, Alaska State Library, Juneau.

The "Gallant, Gentlemanly Oriental" Contractor

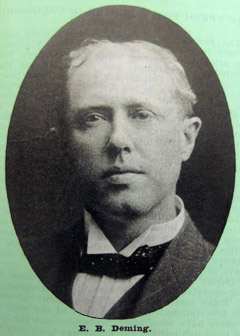

The Radtkes say that Goon Dip 阮洽 a Chinese resident of Portland, began supplying cannery labor to E. B. Deming, the most important salmon packer in Puget Sound, as early as 1900. HistoryLink says that Deming and Goon Dip did not meet until 1909, in connection with the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. Whenever they met, the two became not only business associates but also fast friends. In 1918, The Shield, published by Deming's Pacific American Fisheries, printed an appraisal of Goon Dip that must have been dictated by Deming himself:

"No history of the phenomenal growth and present day greatness of the Pacific American Fisheries would be complete, did it not include and give credit to the important part in that development played by that gallant, gentlemanly Oriental, Goon Dip... A business man par excellence--shrewd, astoundingly so--generous to the supreme and everlasting hilt--a good winner and a better loser, above all, Goon Dip is what is known as a "damned fine friend" His contracts covering all the company's canning operations since its very birth, have been always fair, always just, and by the same token, always very businesslike." Quoted in Radtke and Radtke, Pacific American Fisheries, Inc., 2002: p 64

Bellingham-based Pacific American Fisheries (PAF) was second in size only to the San Francisco-based Alaska Packers Association. At one time, PAF had thirty canneries in Washington, Alaska, and British Columbia. Its workers, at first mainly Chinese and then increasingly Japanese and Filipino, must sometimes have numbered in the thousands. If Goon Dip's contracts did indeed cover all of the company's canning operations, this alone was enough to make him a very wealthy man.

Other European-Americans too found Goon Dip to be exceptionally likeable: for instance, his mentor Ella McBride and the AYPE President, J. E. Chilberg

Goon Dip with wife and daughter, Seattle, 1911. Photo from Goon Dip's grandson, Dick Kay

The Advantages of Cross-Cultural Social Skills: Goon Dip and E. B. Deming become friends as well as business associates 砵倫-西雅图 阮洽受人尊重

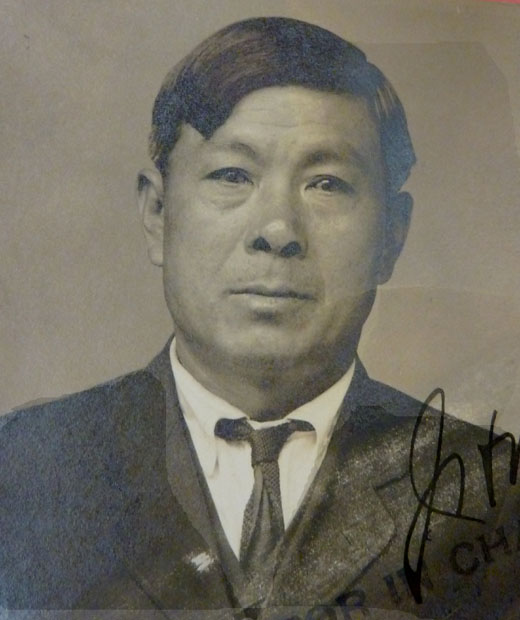

Ah King: Showman and Cannery Contractor, Seattle 西雅图阿倾工约

Ah King (Ng Hock Moy) made his name as the sole Chinese-American vendor for the 1909 AYPE (Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. Although he died mysteriously in 1915, his son continued the labor contracting business under the name of the Ah King Company, also known as Ken Chung Lung & Co. 乾昌隆. The bilingual pamphlet shown on the Labor page, detailing rules for workers and issued in the 1920s, cannot have been read or understood by the average worker, who was likely to be illiterate in both English and Chinese. It must have been intended as a reminder to supervisors and as a legal basis for disciplinary action. The document emphasizes that laborers were expected to work hard and that they would get little or no protection in the event of illness, accident, or labor disputes..

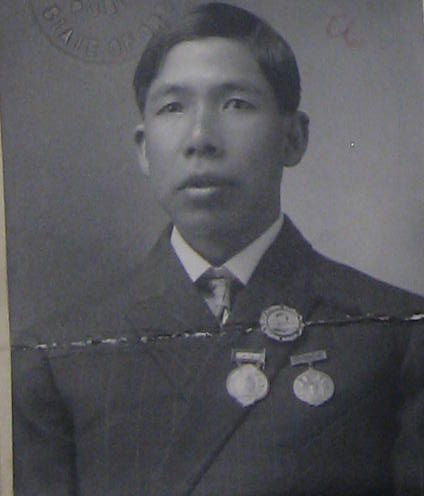

Ah King, Seattle, ca. 1910

E. B. Deming. Photo from Pacific Fisherman 1910-3 p. 11

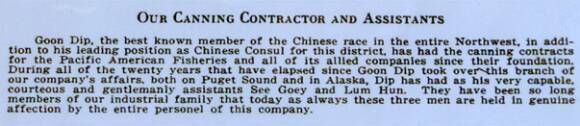

A Contractor's Capable Assistants 西雅图阮洽得力助手

The ability to maintain long-term relationships with clients was evidently the key to success for a labor contractor, and big contractors needed assistants who could help with this. A major problem for those contractors, one imagines, was finding assistants whose English and interpersonal skills were good enough. Goon Dip 阮洽 seems to have solved that problem, however. His two assistants in carrying out the Pacific American Fisheries (PAF) contracts at Bellingham were regarded as exceptionally competent. So was his principal assistant, his son-in-law Lew Kay. Kay ran Goon's contracting and mining empire successfully for a number of years after his father-in-law's death.

In connection with one of Goon's cannery assistants, G. Biery, a long-term PAF employee in Bellingham, wrote: "See Goey was our local boss, who got to know all the local high school girls and boys by name." The caption below, from an issue of the PAF house magazine, The Shield, vol. 1, No. 8, 1918 confirms that both See Goey and Lum Hum got along well with white Americans.

Dick Kay, the son of Lew Kay, informs us that See Goey kept on working in the Goon Dip Co.'s Seattle office as a general helper after the company and the PAF parted ways in the 1940s-1950s. Willard G. and Silas G. Jue, in their influential mini-biograhy of Goon Dip (in the Annals of the Chinese Historical Society of the Pacific Northwest, 1984, pp 46-50), state that See Goey (whom they call Lum See Goey) and Lum Hum became foremen for Goon at E. B. Deming's Bellingham canneries about a year after Goon became sole labor contractor for Deming. However, the Jues believed that Deming and Goon first met at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909, an idea picked up by HistoryLink. This is incorrect. In fact, Deming and Goon had been working together for nine years by then, and both Lum Hun and See Goey had been Goon's foremen for almost that long.

A Chinese social system with businessmen on top [03-18-2013]

Seeking status by purchasing official honors [03-18-2013]

Labor contractors 包工头[05-30-2012]

Merchants as contractors 华人商家兼职工头 [05-30-2012]

Cannery contractors for the APA, 1892-1908. 亚拉斯加罐头鱼业华工头 [05-30-2012]

Cannery contractors in Northwestern Oregon 砵仑地区罐头鱼工头 [08-26-2012, revised

In Portland [10/03/2012]

阮洽受人尊重 [06-23-2012, revised 07-20-2012]

Goon Dip's "capable, courteous, gentlemanly" assistants: 西雅图阮洽得力助手 [08-13-2012, revised 09-09-2012]

Chin Gee Hee seeks a railroad labor contract [09-02-2012]

Chin Gee Hee builds his own railroad [09-03-2012]

The True Strory of Chin Gee Hee's Past? [06-30-2013]

Young Chin Gee Hee as "Ah Ham" in California [06-30-2013]

Merchant-manufacturers 商人.企业家

Merchants as opium refiners in Victoria, BC [08-20-2012]

A public-spirited narcotics cartel? The modest profits of Victoria's opium makers 域多厘烟商利润低 [08-21-2012]

Victoria merchants win an opium price war against a giant Macao exporter 域多厘商人压倒澳门烟商 [08-22-2012]

Ah King was probably no tougher with his workers than any other labor contractor. By the 1920s, after his death, his company seems positively benevolent--it was even paying overtime. And yet Ah King was no saint. Like his fellow contractors, he cannot have been all that concerned about the long-term welfare of his workers. The main exception to a typical contractor's exploitative attitude may have involved kinsmen and others with the same family name from the same home district in China. In Ah King's case, he seems to have made an effort to hire men named Ng from his home town, Taishan, to serve as staff for the Chinese Village at the AYPE. Oppressing workers who were home town kinsmen, one imagines, could have led to real trouble for contractors, both in the U.S. and back in China.

This page was last updated: August 30, 2018

Goon Dip: Contractor, Mine Owner, Merchant: Seattle & Portland 阮洽生平事迹

The fullest and most influential biography of Goon Dip is that of Willard G. Jue and Silas G. Jue ("Goon Dip: Entrepreneur, Diplomat, and Community Leader," Annals of the Chinese Historical Society of the Pacific Northwest, 1984, 14 pages). As grandsons of their subject, the Jues had access to family traditions and oral data but did not examine all available documents or, understandably, take a critical approach. Frank Chesley's on-line article for HistoryLink, which depends heavily on the Jues' treatment, has similar limitations. For instance, it skates over the delicate issue of Goon's relations with his early patron, the young Ella McBride, and accepts that his founding of garment workshops in Portland's Chinatown represent charity rather than exploitation. HistoryLink also follows the Jues in stating that Goon first met E. B. Deming of the Pacific American Fisheries at the AYP Exposition in 1909, whereas by then Goon had already been working with Deming for about a decade. And both sources fail to ask several key questions: how Goon Dip managed to

Other Mentions of Goon Dip in this website

from a neutral Chinese diplomat

Merchants & Manufacturers 商人.企业家

Many labor contractors also owned stores. While they often made most of their money from contracting, many undoubtedly derived significant parts of their income from retail and wholesale operations. This was especially true when some of the goods to be bought and sold could be manufactured by the store keepers themselves.

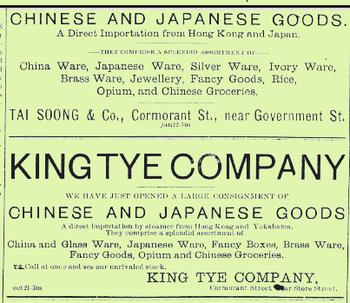

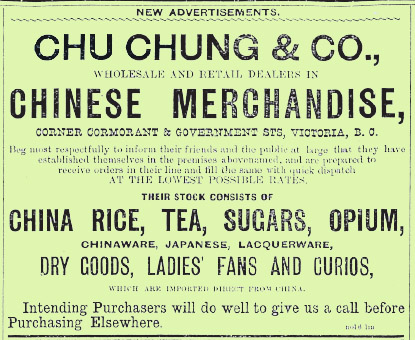

Noteworthy examples were the opium refiners of Victoria. Most of the larger merchants of that city produced opium for smoking, buying raw Indian opium through Hong Kong and selling refined opium for a substantial profit. Several did other business on an equally large scale. For instance, on December 12, 1879, Tai Soong was advertising 100 tons of Peruvian sugar from Callao (in Peru) and in 1887-8 placed numerous advertisements for "Chinese and Japanese fancy goods" in English-language newspapers (see below).

Opium Refiners in Victoria that Lasted More Than Five Years 域多厘烟商

Chu Chung, & Co. 兆昌 [PY: Zhao Chang] 1882-1899, Cormorant & Government Sts.

Fook Yuen/Yen & Co. 福源 [PY: Fu Yuan] 1884-1896, 103 Fisgard St.

Hip Lung & Co, 協龍? [PY: Xie Long] 1889-1901, 22 Cormorant St.

King Tye Co. 乾泰 [PY: Qian Tai] 1884-1892, Cormorant near Store Sts

Kung Wong On Lung & Co 1901-1908

Kwong Chung & Co. 廣昌号[PY: Guang Chang] 1883-1889, Cormorant St. btw Government & Store Sts.

Kwong Lee & Co. 廣利 [PY: Guang Li] 1860-1904, Cormorant St. btw Government & Douglas

Kwong On Lung & Co. 廣安隆 [PY: Guang An Long] 1884-1924, 32 Cormorant St.

Kwong On Tai. 廣安泰 [PY: Guang An Tai] 1885-1890

Lun Chung & Co. 聨昌号 [PY: Lian Chang] 1881-1908, Cormorant St btw Government & Store Sts.

Quong Man Fung & Co. 廣萬蘴 [PY: Guang Wan Feng] 1894-1920, 20 Cormorant St.

Shon Yuen, 信源 [PY: Xin Yuan] 1905-1926

Sing Wo Chan. 成和棧 [PY: Cheng He Zhan] 1886-1889 (not a merchant: a specialized opium refiner)

Tai Soong. 泰巽号 [PY: Tai Xun] 1862-1902), Cormorant nr Government Sts.

Tai Yune/Yuen & Co. 泰源 号[PY: Tai Yuan] 1875-1908), 135 Government St, 14 Cormorant St.

Yan Wo Sang 1860-1865

Note: Romanized names are those used by these firms in English-language documents and advertisements. Pinyin (PY) names are in parentheses. In some cases we do not know the names in Pinyin or Chinese characters.

Display advertisement from Daily Colonist 1888-02-05

Display advertisement from Daily Colonist 1888-02-05

Only Sing Wo Chan, to be discussed presently, specialized in opium. The others were general merchants for whom opium was a significant but hardly all-important part of their businesses. As the next article shows, the profits from opium refining were quite modest. For most shops, opium was a sideline which, though it did not produce profit margins as enormous as those of the modern tobacco and liquor industries, did at least help to keep wholesale and retail customers coming through the door. The fact that some of those customers were (mostly white) smugglers who bought large amounts of opium each time, was an added reason for refining the drug rather than just selling it. (For more opium data click here)

The Modest Profits of Victoria's Opium Refiners 域多厘烟商利润低

One is used to the idea that dope means big money. In our present world, producers, smugglers, wholesalers and retailers of opiate narcotics, cocaine, amphetamines, and even marijuana are reputed to make profits of several hundred percent at each stage of the producer-to-user pipeline. .Even alcohol offers healthy margins. Bar owners routinely mark up their alcohol by several hundred percent, and alcohol makers expect a profit of at least 85% on beer and 90% on distilled liquor (www.probrewer.com/resources/distilling).

Seen in this modern light, one is surprised to learn that 19th century opium refiners in Victoria worked with much tighter margins. In the 1890-1 fiscal year, Chinese refiners in that city imported 125,411 pounds of raw opium, which was valued at $296,764 (S.F. Call 1891-10-18). A customs duty of approximately $1 per pound (I.e., $160/case for a 140-160 pound case--British Colonist 1888-05-08) should be added, bringing the cost to $3.37 per pound. The per-pound cost was doubled by the refining process, which reduced the weight of opium by about 50%. Hence, the raw material for each pound of finished product came to roughly $6.75. Allowing for labor, overhead, and packaging, the total cost to the refiner cannot have been less than about $7.00 per pound or $2.86.per standard 5-tael (6.54 ounce avoirdupois) can.

The refiner could expect to get $4.25 per can at wholesale, yielding a profit of 48.6%. Naturally, he could increase this profit by using smuggled raw opium, by cutting corners on the refining process, or by mislabeling his product to look like one of the high-grade Hong Kong-refined opiums, which in the U.S. retailed for as much as $11-12 per pound. All those dodges undoubtedly were tried. On the other hand, opium smokers were a knowledgeable and choosy clientele. A refiner who tried too many tricks could hardly hope to stay in business for long. (For more opium data click here).

Victoria merchants win an opium price war against a giant Macao exporter

域多厘商人压倒澳门烟商

"The Sing Wo Co. are an immensely wealthy firm and manufacture at Macoa [sic] the finest opium, known in the commercial world as the 'Tai Yuen brand' [a typo for Lai Yuen brand--eds.]. It obtains a higher figure than any other brand of the seductive drug.

"A few years after the Chinese arrived in this province the manufacture of opium was begun in Victoria, and for many years was a very profitable business to both the manufacturer and the "exporter" [i.e., the smuggler--eds.]

"The Sing Wo Co. started a branch in Victoria three years ago under the name of the Sing Wo Chang Co., with the avowed object of driving the other firms from the trade. To accomplish this they reduced the price from $10 to $7 per pound. However, they did not succeed, the other factories having a general business to aid them in fighting the Sing Wo, who manufacturer opium exclusively...

"It is stated that the Sing Wo Chang Co. have lost $40,000 during the three years of warring against the other firms, and are likely to lose more if they keep up the fight, for the local firms show no sign of giving up." (Victoria Colonist 1888-05-08; see also 1888-06-21)

An opening salvo in Sing Wo Chan's war: its first ad in the English-language press, from the Victoria British Colonist

The advantage of having other income sources during a price war is vividly illustrated by the following article on an attempt by a large, rich Macao-Hong Kong firm to muscle into the Canadian opium refining business. The article also shows that opium refining, though profitable, was not so important to Victoria's general merchants that they could afford to neglect trade in other commodities such as rice, tea, sugar, chinaware, ivory, silver, brass, silk, Chinese groceries, and Japanese lacquer (see the Chu Chung, King Tye, and Tai Soong ads under "Merchant Manufacturers" above).

"Sing Wo Chan" ( 成和棧, Cheng He Zhan) seal on an opium can from a 19th century Chinese mining site in central British Columbia

Sing Wo Chan had first opened its doors in 1886. By 1890, it was gone. For more on the opium business in Victoria and nearby areas, see the relevant parts of the main opium pages of this website.

The above photograph was taken from an issue of The Shield preserved in the Photo Archive of the Whatcom County Museum, Bellingham. We thank archivist Jeff Jewell for leading us to this source.

The northwestern corner of Oregon was second only to San Francisco in the number of cannery labor contractors based there. Many provided labor for canneries along the nearby Columbia River but others sent laborers to canneries as distant as western Alaska. The following list is compiled from the Oregonian, records of the Alaska Packers Association (APA--see above), the Pacific American Fishery (PAF) in Bellingham's Western Washington University library, the Columbia River Packers Association (CRPA) in Astoria's Maritime Museum, the Astoria city directories in the Astoria Public Library, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Seattle, and Chris Friday's seminal book Organizing Asian American Labor, published in 1994.

Not surprisingly, many of the individuals involved were leaders of the Chinese community in the region; cannery contracting could yield substantial fortunes. The big three contracting companies appear to have been Twin Wo, Wing Sing, and Kwong Man Yuen. The numbers in brackets are years when cannery activities were noted in the consulted sources.

-- Woo Tai Co, 31.5 North Third St. (1897-1907). Manager: Ding Wing 邓荣. Ding had lived

in Portland since 1877 and died in 1933, making him one of the most senior Chinese residents

of that city. His son, Harry Ding, performed in Seattle's 1909 AYP Exposition.

-- Hong Fook Tong 同福堂 (1895-96)

-- Hong Yick & Co, 恒益/同益?, 81 Second St. (1893-94). Manager: Chew Fung.

-- Hop Chong Lung Kee & Co合昌隆记, 60-62 Second St. (1905). Managers:

Louis Kin雷健, Louie Seid.

-- Hop Wo Lung & Co 合和隆 (1899)

-- Hop Yick Wo & Co 合益和杂货, 85 Second St. (1905). Manager: Charles B. Young.

Young, of Chinese ancestry and the husband of husband of Mary Byl since 1893, was

associated with the Kwong Sue Co. in 1909.

-- Jim Whalen (1894). A child of a cross-ethnic union, Whalen was in Portland in the1880s

and had more than one brush with the law. In 1894 he appears to have done some

contracting business, according to the Oregonian.

-- Kwong Chong Lung & Co 广昌隆, 89 Second St. (1894).

-- Kwong Lun Tai & Co广联泰, 61 Second St. (1901-09). Manager: Lee ? 李美近.

-- Kwong Man Yuen Co 广万源, 93 N Fourth St.(1907-17). Manager: Wong On 黄安.

Wong was portrayed as an evil contractor in a 1917 federal hearing. A resident of

Portland between 1885 and 1944, he also owned the Hung Far Low and Burnside

restaurants in later days, as well as a branch of Kwong Man Yuen Co. in Seattle.

-- Lau Fong, (1933).

-- On Chung Wa & Co 安昌和号140 Second Street (1881-1904). Managers: Lee

Foo 李辅, Chan Kee Dan 陈基典. Lee was among the few native born contractors.

He was born in Portland in 1879 and joined On Chung Wa at he age of 18.

-- On Hing & Co 安兴 66 Second St. (1895-1912). Manager: Chin Wing 陈荣;

Secretary: Gen Wing. Chin was a founder of Portland's Chinese Consolidated

Benevolent Association (CCBA) in the late 19th century and in 1909 became a board

director for Portland's new Chinese School. Among the longest lasting Chinese cannery

contractors for the Alaska Packers Association, Chin was at odds with his competitor,

Seid Back of Wing Sing & Co.

-- On Kee Co, (1910)

-- Wing Sing & Co (Wing Sing Long Kee & Co) 永盛, 308 Front St,(1886-1930).

Managers: Seid Back 薛柏 and his son Seid Gain Back 薛天眷; Other Positions: Sit

Que, Lang Bone, Suill Duck; Foremen: (1934): Seid Sing Don & Seid Fook Gee

薛福如. The Seids was among the few Chinese who owned or were major stockholders in

canneries, including the Fidalgo Island Co. in Anacortes, Washington.

Cannery Labor Contractors in Northwest Oregon 1898-1935

砵仑地区罐头鱼工头

Mo Chung Way

Ding Wing in 1923

Lee Foo in 1917

Seid Gain Back in 1910

Wong Onin 1914

Seid Chuck in 1912

Chin Wing in the 1900s

Canneries Past and Present - Fred Wong's story 砵仑黄国民 三代罐头鱼业

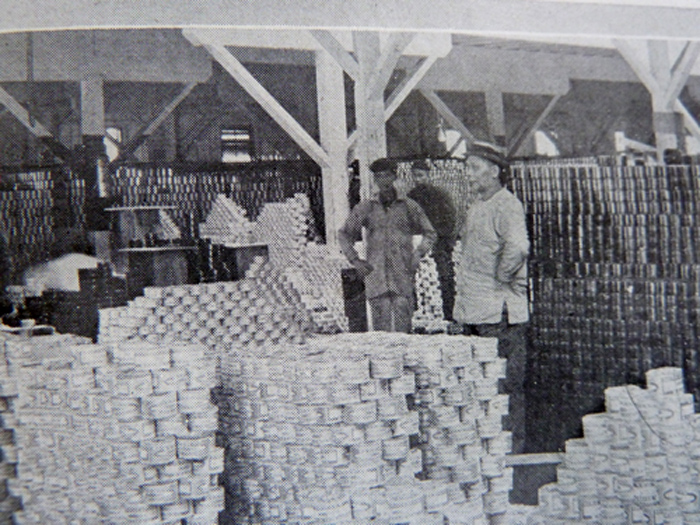

Chinese butchers at the PAF (Pacific American Fisheries) cannery, Bellingham, Pacific Fisherman, 1906.

Chinese foremen? on a PAF packing line. The Shield, 1918.

The sorters separate types of fish in bins ready for butchering, 2008

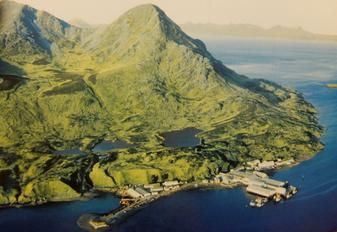

Alitak Cannery, Kodiak Bay, AK. Built in 1917 and still in operation, owned by Ocean Beauty Seafood.

Foreman Fred Wong, second from left, with his assembly line, Alitak Cannery, 2008. Fred is also a director for Portland's CCBA.

In 2008 Fred Wong of Portland retired from Ocean Beauty Seafood as a foreman at their cannery in Lazy Bay, Kodiak Island, AK, after working in canneries for almost 50 years. He began as a teenager, left cannery work briefly while in the army, but continued afterward. He went back to the canneries every summer, first as a college student and then as a high school teacher. Canning salmon was a family tradition. His uncle William worked in an Alaskan cannery in the 1920s. His father, Herbert Wong, became a cannery contractor in the 1920s. And his three daughters all had summer jobs in canneries while young. Canneries are a good place to work, Fred says, "They paid for my college, and much more."

Photo credits: We thank Fred Wong for the interview and color photographs. His father's photograph comes from the Portland CCBA .

Herbert Wong Deyao was a major donor to the building of the CCBA's auditorium in Portland in the 1930s

(UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED ALL DATA ON THIS PAGE COMES FROM THE EDITORS' OWN RESEARCH ON PRIMARY SOURCES & ARTIFACTS)

Goon Dip, Seattle, 1905?

Chin Gee Hee 陈宜禧 (Pinyin: Chen Yixi): Railroad Contractor, Merchant, Visionary Capitalist

Chin Gee Hee may have been the most intelligent Chinese businessman in the early history of the Pacific Northwest. He is also the best-studied and, thanks to the extensive collection of papers he left behind, one of the best-documented. An excellent biography is available on Wikipedia. Here we have only sought to fill in a few gaps in what is known about his history.

Chin Gee Hee Seeks a Railroad Labor Contract

Personal

Seattle Wash, March 14th 1895

A. H. Warren, Esq. General Manager St. Paul

Dear Sir I beg to thank you for the box of cigars which you sent to me through Mr. Stevens, which were most highly appreciated and enjoyed. I have the labor contract matter up with Mr. Barr, having called on him while in Spokane and think that it will be arranged satisfactorily. I don’t think he has determined the question of rate of wages that would be proper, the Northern Pacific paying $1.05 and $1.10 and the O. R. & N. [Oregon Railroad & Navigation Co.] 95 cents. There are reasons for this low rate on the O. R. & N. which may not at first be apparent. They have the cooperation of the management, close to the base of supplies and what is better still a very large number employed. While on your line I have to bear the expense of the establishment and introduction of our men, I have to provide for their safety and overcome any ill feeling that might break out. I assure you there is no trouble in doing this and doing it thoroughly, but not without the use of money and of course I would be the one to bear this expense. However, I have no doubt that you will treat us fairly. Our export flour business is suffering greatly from lack of steamer space, it seems almost impossible for us to get more than three or four hundred tons space in each steamer, very often not more than 200 tons. This is on the N. P. S. S. Co. [Northern Pacific Steam Ship Co.] The situation with the Empresses [ships of the Canadian Pacific] seems to be no better. So you think likely that Mr. Hill will be out this way very soon. If we don’t get relief from your people I don’t know where it will come from. The N. P. S. S. Co. have put on another boat being due here July 21st on its initial trip, but it will take several more to fill the demand at the $6.00 rate.

Yours respectfully

Quong Tuck by Chin Gee Hee

Seattle Wash. March 14th 1895

J. M. Barr, Esq. General Superintendent, Great Northern Ry., Spokane, Wash.

Dear Sir I find your favor of the 6th inst. on my return from Spokane. In case your decision is favorable to us, I would like to ask that you inform me at your earliest convenience for the reason that the season of the year is now approaching when there is considerable demand for our men on farms and in fishing industries and while of course this will not entail any inconvenience to you, it means some little expense to me should they become scattered before you need them. However, this is a matter for my own look-out as of course I will furnish the men promptly whenever called for, but I merely write to inform you that anything in the way of an idea or opinion as to your probable action, would be of great value to me and would be highly appreciated. I send you under separate cover a small package which I beg you will accept with my compliments,

Yours respectfully

Quong Tuck Co.

These two letters have survived in the Willard G. Jue Papers in the University of Washington Library Special Collections. They depict an ambitious entrepreneur who is already moving in high-level American business circles. James Hill, whom he mentions in the first letter and was one of the country's leading railroad magnates, would later get to know Chin personally and take a friendly interest in his Chinese railroad plans.

It will be seen that both letters are structured similarly, with first a request and then a mention of a reward: in Warren's case, of contracts for the trains and ships of the Great Northern to handle Chin's extensive wheat flour exports to Asia and, in Barr's case, what sounds very much like a veiled offer of a bribe. The letter to Warren artfully brings in all three of the GN's main rivals in the flour export trade: the Northern Pacific, the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Co. (already closely cooperating with, and in 1898 taken over by, the Union Pacific), and the Canadian Pacific. Was Chin hinting that he might give his freight work to one of them if he did not get the Great Northern labor contract? Probably.

Chin Gee Hee: a modern statue in Taishan city, Guangdong province. It does not look much like him

secure the Chinese honorary consulship in Seattle when Chin Gee Hee wanted the job, what his connections were with the secret societies that then dominated Portland's and Seattle's Chinatowns, and why he did not become immensely wealthy, rather than just well-to-do, through his management of (and ownership of a major share in) the Hirst-Chichagof Mine, at that time the richest gold mine in Alaska and one of the richest anywhere.

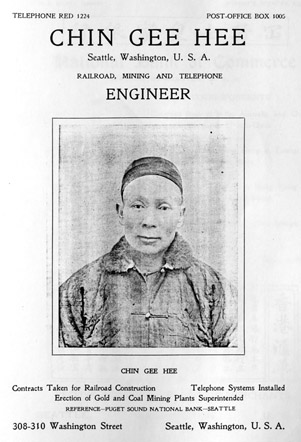

Chin Gee Hee advertises as an engineer, not a merchant

Probably no other early Chinese businessman in North America had acquired enough technological expertise to call himself an engineer. Chin, however, had. Due to restless curiosity and an exceptionally high IQ, he overcame a complete lack of formal education to absorb enough of the leading-edge technologies of his day not only to bid for contracts in those fields but to supervise the building of entire high-tech systems.

Thus far, we know nothing about the telephones he installed or the mining plants he erected. With regard to railroads, however, the records show real expertise. He began as a labor contractor for railroad construction projects, playing a major role in the building of the Seattle and Walla Walla Railroad as early as 1876 (C. Bagley, History of Seattle, 1916: p 246). Later he worked extensively with the Northern Pacific and Great Northern before building a railroad of his own.

As indicated in the following Wikipedia quote, there is disagreement over the extent of non-Chinese involvement in the Sun Ning project. The next quotation, from the Railway Age Gazette, resolves this issue. Railway Age was the leading professional railroad publication of its day, and exceptionally well informed. If James Hill or his peers had invested money in the Sun Ning railroad, Railway Age's editors would have known.

Chin's crowning achievement was the construction of the Sun Ning (Xinning) Railway in southern China, giving his home town of Toisan (Taishan) access to a river port on the Pearl River estuary. Chin bought mainly American equipment and rolling stock of the kind he was familiar with. But in spite of this, his funding was Chinese-American, not European-American. How many design details were his own is not clear, but he clearly had much of the needed expertise.

His company, Quong Tuck, was still a mercantile firm that handled ordinary retail and wholesale transactions, the importing and exporting of goods, cannery contracting, and finding Chinese domestic servants for white households. Interestingly, the Chin Gee Hee papers show that, while working on more glamorous projects, he continued to deal personally with routine business--for instance, he put substantial effort into the buying and selling of soap.

"In order to fund the railway, Chin raised $2.75 million, mainly from overseas Chinese; some sources say that further investment came from James J. Hill, but others say that at a time when railway development in China was dominated by European nations,he 'vowed not to sell shares to foreigners, to borrow money from them, or to use their engineers.' "

(Wikipedia, "Xinning Railway")

"The (Sun Ning) railroad was constructed by Chin Gee Hee, who acquired his knowledge of the railway business by active construction work on the Northern Pacific and other northwestern railways of the United States many years ago, and who constructed this line largely with money subscribed by Chinese now in the United States."

Railway Age Gazette 1912, vol 53, p 888

The only surviving locomotive of the Sun Ning/Xinning Railroad, now in the Wuyi Museum, Jiangmen, Guangdong

Sun Ning/Xinning Railroad logo

Display Ad from the International Chinese Directory, 1901, San Francisco

Chin Gee Hee Elsewhere on this Website

1844-73 The True Story of Chin Gee Hee's Past: part of the accepted biography is false

西雅图早期华侨陈宜禧商业档案中的医方

unpublished notes 西北角中文地名

陈宜禧夫人早产

Consolidated Benevolent Association in Seattle

to Seattle

不倔不挠话曾爱

Chin Gee Hee Builds His Own Railroad

Chin Gee Hee monument in Taishan city, Guangdong province.

Yip Sang: Merchant, Railroad Contractor, Family Founder in Vancouver

The Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online includes a solid brief biography of him by Timothy J. Stanley, based partly on a Chinese-language biography published in Hong Kong and on archival records in the Vancouver Museum and Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria. The following paragraphs are quoted from the Dictionary. It will be noted that, contrary to what is sometimes written, Yip arrived in Canada too late to be a contractor for the Canadian Pacific's first transcontinental line, completed in 1885. Hence he was not responsible for the harsh treatment that Chinese contract laborers received under the notorious Andrew Onderdonk.

"Yip came to Canada in 1881 to work on the Cariboo goldfields. Unsuccessful there, he moved to what would become Vancouver and sold coal door to door until he was employed by the Canadian Pacific Railway Supply Company on a construction gang. He became the company’s bookkeeper, timekeeper, and paymaster, and eventually its superintendent of Chinese labour. In 1885 he returned to China and took a fourth wife.

"In 1888 Yip founded the Wing Sang Company in Vancouver. Like many Chinese firms at this time, Wing Sang engaged in a variety of enterprises. In addition to labour contracting, the company ran a transpacific import and export business, pioneering the export of salt fish to various points on the Pacific rim, including Japan. It also played an important role in forwarding remittances from workers to their families in China and serving as a contact point for correspondence. Yip became the Chinese agent for the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, supplying its railway with construction labourers and its steamships with sailors and fresh produce."

Yip Sang (葉春田, Ye Chuntian) was the Canadian counterpart of Goon Dip. Like Goon, and unlike Chin Gee Hee, he committed himself to life in Canada. His four wives all came from China to Vancouver where they lived with him, his many children (including at least 18 sons), and several generations' worth of nephews and cousins (click here for more data). Numerous family members were employed in his various enterprises. Unusually for that period, he gave educations to his nieces and daughters and encouraged them to play public roles in such organizations as the Empire Reform, Association (click here for more data).

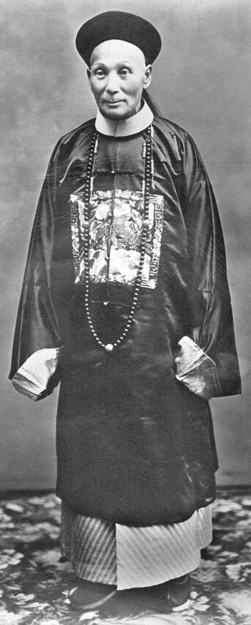

Yip Sang, ca. 1920, from portrait photo in the Vancouver Museum.

Yip Sang in 1909. Immig-ration Service photo in NARA, Seattle.

The editors believe that Yip Sang Sang owned shares in a number of canneries. Counting in his salt fish business, Yip may have had a direct financial interest in more seafood processing operations than any other North American Chinese,

-- Ah Kow (1878)

-- Charley Koe (1940)

-- Chong & Wo Co. 368 Bond St. (1906)

-- Chong Chong. 314 Bond St. (1902)

-- Dark Lung & Co. 德隆 310 Bond St. (1902)

-- Hong Yick & Co. 同益/恒益. 340 Bond St.

Partners: Chew Mock, Chew Chew, Chew Sun,

Chew Sam, C.W. Wong. (1902)

-- Hop Hing Lung & Co. 合兴 376 Bond St.

Partners: Chin (or Chan) Ah Dogg. Other

partners: Go Yen, Wong Ming Ho, Leong Yick,

Jeong Joe, Chew Nung, Yee Chew, Lee Chee,

Lum On, Chew Que. Chin Ah Dogg was also a

partner in On Hing & Co, another contracting

company in Portland.

Photo credits: The images of Mo Chong Way and Chin Wing are from Portland's CCBA photographic records. We thank Victor Leo and Marcus Lee of the CCBA for their help. The other images are from the Chinese Exclusion Files, National Archives & Records Administration, Seattle: Ding Wing (File 5016-306) , Wong On (5009-206), Lee Foo (5009-15), Seid Gain Back (5017-148), Seid Chuck (5010-494), Chin Ah Dogg (Van 507), Go Yen (Sumas 1017), Lum Chack (Portland 3134), Wong Yuen (RS 18386).

Portland 砵仑

-- Chan Yuen (1901)

-- Chin Jim (1914-1927).

-- John Wo & Co 进和杂货, 82 Second St.(1887-1909). Manager: Mo

Chung Way 巫昌渭.(a.k.a. Mo Lee Tong 理唐, the volunteer accountant

for Portland's Chinese School in 1909, a major donor for the construction

of' Portland's CCBA auditorium in later years.

-- Dai Kan (1901)

-- Seid Bing (1909). Seid's brutal murder in Seattle in 1912 became

headline news in many Northwestern newspapers. .

-- Seid Chee, 287 Flanders St, (1921)

-- Seid Chuck 薛泽, (1908). Seid Chuck was probably a one-time

contractor (see Seufert Brothers Cannery records, Mss 1102-18/-18. in

the Oregon Historical Society). He was a cannery foreman in the 1930s.

-- Twin Wo & Co 聚和号, 244 Yamhill St/233 Second St, (1889-1913).

-- Wing Ah Chung (1910)

-- Wing Wa Lung Co 永华隆, (1898)

-- Wong Yuen, (1920s).

Astoria 挨市左利埠

Most Chinese contractors in Astoria seem to have come from Xinhui County in Guandong, then famous for its high level of education.

Chin Ah Dogg, 1911

Wong Yuen, 1906.

Lum Chack, 1913

Go Yen, 1908.

-- Kong Lee Wo & Co. 公利和. 351 Bond St.

-- Kung (Kwong) Wing & Co. 广荣杂货, 318 Bond St. Partner: Lum Dong.

-- Leong Yip. Contractor for the CRPA in 1899

-- Mee Gin Jan & Co. 美珍栈. 354 Bond St. Partners: Lum Lop Wy, Lum

Shin Yuen, Lum Dock Tse, Lum Yoke, Kong Sai Get, Lum Lun, Lum Duck

Gam, Lum Bong, Lum Chack 林焯, Lum Chew, Lum Loy.

-- Quong Chong 广昌. 314 Bond St.

-- Sam Kee & Co 三记 (1892). 116 9th St.

-- Sun Yuen Lung & Co. 新源隆. 125 9th Street. Partner: Go Yen 高恩

-- Wah Hing Jan & Co. 华兴栈. 360 Bond St.

-- Wing Chin Chong. 78 8th St.

-- Wing Sang & Co. 永生. 372 Bond St.

-- Wing Yuen Co. 125 9th St. Partners: Go Yen, Go Fan, G.J. Howe,

Go Lock, Go You, Bow King, Lum Long, Go Sing, Hip King, Chun Chai.

Go Yen had interests in several companies. He was also the secretary for

Astoria's Chinese Empire Reform Association or Baohuanghui.

-- Wo Tai Lung & Co. 和泰隆. 368 Bond St. Partners: Chin Ah Dogg,

Lum Shin Yuen.

-- Wong Chew

-- Wong Get & Co.

-- Wong Yuen 黄元. Contractor for the CRPA in 1899, 1900. Wong later

ran a successful American style restaurant in town, the "Astoria."

-- Wong Kee Brown

A Chinese Social System with Businessmen on Top

In China, before the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911, businessmen ranked quite low in the social hierarchy. Very wealthy businessman could buy limited influence, but the levers of power were firmly in the hands of a largely Manchu military and a prestigious and mainly Han Chinese civil service bureaucracy. The situation in overseas Chinese communities was different. In the Western Hemisphere and Southeast Asia as well, individuals who were called merchants but were actually general businessmen played roles that were just as central to overseas Chinese society as were the roles of their counterparts in the United States and Canada to the sociopolitical system of the white majority. In North America, unlike Europe and China, the bourgeoisie were in charge.

A major problem for successful Chinese businessmen in North America was that Chinatowns were small arenas for competition and status display. Unable to enter the world of white business except in a very limited way, and culturally committed to plan for retirement back in his home town, an ambitious Chinese merchant was forced to depend for recognition of his achievements on the overseas Chinese community and on the people of China itself. One way of seeking such recognition was to buy honorary (or even actual) positions within the home-country hierarchy. That option, involving the right to call oneself a ranked Chinese official and to wear the appropriate dragon robes and rank badges ("mandarin squares") is explored on another page of this website.

Chin Gee Hee in 1905. Holding a 3rd grade official rank, he was one of the highest-ranking businessman in the Americas.

5th grade official

6th grade official

Two figures dominate the pre-Expulsion history of Seattle, the merchant contractors Chin Gee Hee, to be discussed presently, and his senior partner, Chin Chun Hock. Because the active career of the former bridges the 1886 Expulsion gap and because family members, acquaintances, and newspapers in both Guangdong and Washington recorded information about him, Chin Gee Hee's life is comparatively well known. However, the same is not true of Chin Chun Hock's life. He remains a shadowy figure in spite of his importance in the history of the region.

Until very recently, almost all published biographical facts about Chin Chun Hock came from a single source: the notebooks of Mrs. Ruth Price, the executive secretary of Seattle's China Club in the early 1950s. Having been assigned by the Club to conduct preliminary research on pioneer Chinese Americans, Mrs. Price took the bit in her teeth and plunged forward on a major research project, filling an "impressive stack of notebooks" with data from library sources plus interviews "with members of the Chinese colony." At least some of the older members of that colony would have known associates of Chin Chun Hock: Chin Gee Hee (1844-1929), Chin Quong (1857-1935; arrived 1868) and Woo Gen (active until at least 1924; his son, David H. Woo, lived until 1992). They could have heard stories about Chin Chun Hock from these or others who knew him. Mrs. Price's notebooks have now disappeared, and she was not a trained researcher. Yet we feel that her description, as recorded by Lucile McDonald in a Seattle Times article, is plausible and worth repeating:.

"Mrs. Price tracked down the story of Chin Chun Hock, whose Wa Chong Co. existed until a couple of years ago. Its proprietors then said it was the oldest business house in Seattle.

"Chin, born in 1844, arrived in Seattle from China in 1860 and eight years later organized the company. Advertisements in 1873 listed its location as Mill [now Yesler] Street. It manufactured cigars, sold tea, and did tailoring. Chin engaged in various other enterprises, though he continued for a quarter of a century using as a symbol of his business the figure of a Chinese weighing tea.

Chin Chun Hock 陳程學 1844–1927

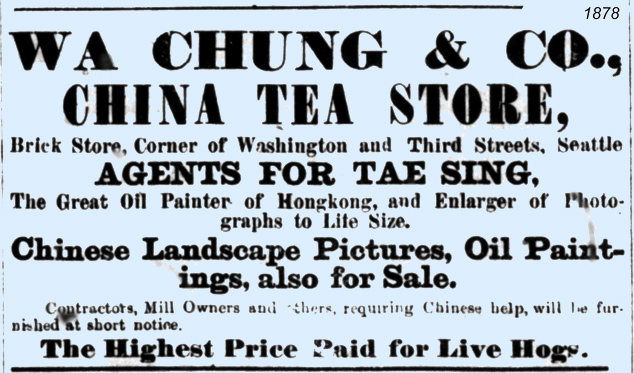

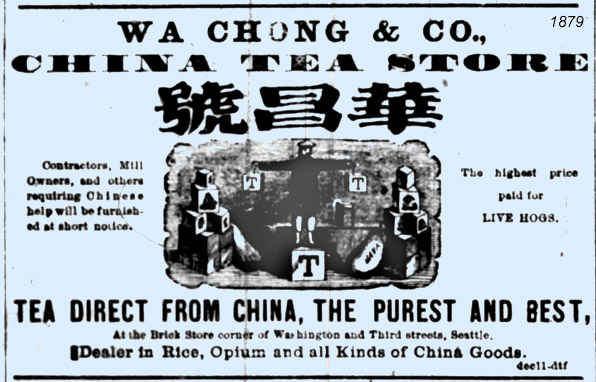

An important part of Chin's business philosophy was to advertise regularly in the English-language press. From the mid- 1870s until the 1885-6 expulsion years, his Wa Chong/ Wa Chung ads appeared almost daily in the Post-Intelligencer and probably in other newspapers, now vanished, as well. These advertisements may or may not have paid for themselves by increasing business. However, then as now, newspaper owners looked favorably on frequent advertisers. The fees involved must have moderated editors' attitudes toward Wa Chung (and other local Chinese) in an age of increasing anti-Chinese sentiment.

1876-12-11 Post-Intelligencer advertisement

1878-01-10 Post-Intelligencer advertisement

1879-08-10 Post-Intelligencer advertisement;

1883-07-06 Post-Intelligencer advertisement

1872 Puget Sound Business Directory: Wa Chong is one of three Chinese shops listed under Cigars & Tobacco

"Chin once remarked that there was a swamp behind his first store and he shot wild ducks there. The wooden structure built on stilts over the march stood on the later site of the Pacific Building.

"Contracting was one of Chin's activities. He supplied labor for building the coal railroad to Newcastle [i.e., the Seattle and Walla Walla Railroad, begun in 1874] and was quoted as saying 'I graded Pike, Union, Washington and Jackson Streets. At one time the city owed me $60,000 for six months. I had to sue to recover it.'

"Chin also exported Pacific Northwest products to China, as much as 4,000 barrels of flour to Hongkong in one shipment." (Seattle Times Sunday Magazine1955-9-11, p 2)

(Both of these show the Wa Chong logo mentioned by Ruth Price, of a Chinese man weighing tea)

Much more information on Chin's large family (he had 12 or 13 wives, including a Native American, Mary Carey, called "an Indian princess") is available in a blog by various descendants (see Wikipedia's "Chin Chun Hock" entry, External Links) and on a new Facebook page. Details about his business life are scarce, partly because his junior partner (and cousin) Chin Gee Hee was given much of the public credit for construction projects handled by the Wa Chong firm.

Newspapers in Seattle and Victoria recorded that Chin Chun Hock returned to Seattle from San Francisco (and China?) with a (unnamed) wife in February of 1878 (Post-Intelligencer 1878-02-23 & -26), that he made two other trips to San Francisco in the same year (PI 1878-09-16 & -11-26), and that he went back to San Francisco with his wife in 1879 (PI 1879-06-27). During part of 1879 and 1880 he was in China, perhaps accompanied by the same wife (Note 1).

In years other than 1877 and 1878, there is little data about his West Coast movements, as local newspapers ceased publishing lists of (first-class only) passengers. However, we may assume he continued traveling frequently. In 1903, the San Francisco Call (1903-07-04) noted that he was stuck at Port Townsend by new immigration rules while returning from Victoria.

Chin Gee Hee played a much more visible role in defending the Chinese community during the frightening Expulsion years,1885 and 1886 (click here). The fact that Chin Chun Hock backed away from taking a leadership role then may have been connected with his and Gee Hee's subsequent divorce in 1888, when the latter left Wa Chong to found a new firm, Quong Tuck & Co. Due to Gee Hee's extensive contacts within the white business community, Chun Hock must have found Quong Tuck to be a formidable competitor. Bad feelings were the result.

The following is by an anonymous contributor to the above-mentioned Wikipedia blog. Although he/she does not provide references, there is no reason to think that the quotation is not accurate or that the feelings involved were not actually felt.

新宁铁路的建成,全县人民皆大欢喜,唯独陈宜禧的叔父、

美国铁路工程师陈程学深感内疚。因为早在陈宜禧行动回乡筑路之前,

曾诚邀陈程学协助。陈程学蔑视陈宜禧的能力,不仅不允,反嘲笑说:

“有尾狗亦跳,冇尾狗亦跳。你如果筑得成铁路,我永远不坐你的火车!

”如今铁路筑成了, 陈程学无颜以对,每次返乡都只好乘船或坐轿。

(Translation) With the completion of the Sun Ning Railroad, the people of the entire county were overjoyed, except for Chin Gee Hee’s ‘uncle’, the American railroad engineer Chin Chun Hock, who felt regretful. Because even before Chin Gee Hee went home to build his railroad, he had invited Chin Chun Hock to help. Chin Chun Hock looked unfavorably on Chin Gee Hee’s capability, however – not only did he disapprove, but he even ridiculed with, “A dog with a tail jumps, and a dog without a tail also jumps. If you build this railroad, I promise never to ride your train!” Now that the railroad had been completed, Chin Chun Hock felt he had lost face, so he resigned himself to taking a boat or carriage when he went home.

Note 1. Chin Chun Hock's 1879-80 visit to China is mentioned by Chin Gee Hee in a letter to his former employer, Ms. John Brown of San Juan, California (Letter book, page 162; Chin Gee Hee Archive, University of Washington Library). In the letter, Gee Hee complains that his partner's stay in China is preventing him (Gee Hee) from gong back to China himself.

The Browns appear as residents of North San Juan, Nevada County, California, in both the 1880 and 1870 U.S. censuses. In 1880, the household included six persons: W. John Brown (40), H. Adeline (34), A. Alice (13), Herbert (11) and R. Joseph (4). Alice must be Allie, and Herbert, Butie. John Brown is listed as a miner. In 1870, the household was comprised of five persons: John H. Brown (31), Adeline Brown (26), Alice Brown (3), William Brown (1), and a cook, Ah Mary (15), born in China. In spite of his name, Ah Mary was male.

Could Ah Mary have been Ah Ham? And only 15 years old in 1870? It seems unlikely. Chin Gee Hee/Ah Ham, if really born in 1844, would have been 26 in 1870. It is hard to believe that the census canvasser, who in those days was supposed to see and count each resident personally, could have mistaken a 26 year-old for a 15 year-old. Perhaps Ah Mary was a substitute servant hired for the period Ah Ham was visiting China and marrying a new (his first?) wife. That visit, which resulted in Ah Ham discovering that his pans had been lost, perhaps by Ah Mary, and Ah Ham's bringing a shawl back for Ms. Brown, cannot have been long before his departure for Seattle in 1873.

The 1860 census lists several Ah Hams, all of them gold miners, in that part of California. One, at Fosters Bar in Yuba county (about ten miles from North San Juan in Nevada county), was recorded as being "ca.17." Conceivably, this was Chin Gee Hee. Like other ambitions Chinese teenagers (for instance, Goon Dip), he might have seen the possibilities in temporarily becoming a servant so as to learn the English language and Euro-American ways.

The True Story of Chin Gee Hee's Past?

The exchange was initiated by Chin on September 16, 1880, writing from Seattle. In that letter, he says "Dear Friends Mr. and Mrs. John Brown, It has been seven years since I left your place. I look back with a great deal of pleasure- all time and would like to see you very much. . . You received my letter please to acknowledged, Ah Ham Gee Hee " [ALB p 159]

Ms. Brown replied on November 1st,1880, writing from North San Juan. "Dear Ah Ham: We were very pleasantly surprised a few weeks ago by receiving a letter from you. I have often thought you must have gone to China to live with your wife. . . Butie and Allie are almost grown . . .You would feel badly to see how hard we all have to work now. Just think of us doing all the washing ironing and cooking for six of us. . . You would sorld [?] around worse than you did to find the pans all lost when you came back from China. . .Your well wisher + friend, Mrs. A[deline] H.Brown.

P.S. I wear your shawl you bought me from China + think a great deal of it." [ALB p 160-1]

Chin's answer of November 24th, 1880, did not reject Ms. Brown's implication that he had worked for her as a cook before going to China and finding on his return that his pans all had been lost. Instead, he wrote "Dear Friend Mrs. Brown. . . Was very much pleased to hear from you. I am . . .very glad to know that Butie and Allie all growing be gentleman and lady and I have been home to China three years ago. Then I like go to China again but my partner he is gone China last years and I have to with [wait?] my partner come back intered [entered] business. I will go I have had three girls + two boys + two wife all living in China, and my children as growing to + our store name Wa Chung. I am owning ¼ one share + my partner he is owning ¾ three shares. . . I think just enough at present. A. H. Gee Hee" [ALB p 162]

Note 1. Chin Lem appears five times (in 1897, 1908, 1813, 1918, and 1923) on U. S. government passenger lists published by Ancestry.com, returning from Hong Kong and (in 1897) from Victoria. On each occasion he gave his birth date as 1877 or 1878, but never as 1875. We have not been able to find an official record of his birth. In any case, his sister Chin Fong See was born in the U.S. in 1871, well before Chin Lem (Chicago Tribune 1888-01-08 p 6)

Note 2. Willard G. Jue, "Chin Gee-hee, Chinese Pioneer Entrepreneur in Seattle and Toishan", Annals of the Chinese Historical Society of the Pacific Northwest, 1983, pp 31-8.

Note 3. Judy Yung, Gordon Chang, & Him Mark Lai, eds., Chinese American Voices From the Gold Rush to the Present. 2006: p 125

Note 4 Doug Chin, Seattle's International District. 2009, pp 38-9

Note 5. Wikipedia, main entry as of 6/2013, "Chin Gee Hee"

Note 6 University of Washington Library, Special Collections: Willard G.Jue Papers, Accession No. 5191-001, Box #1, Folder 12. 69.

The accepted version of the life of Chin Gee Hee, the most important Chinese figure in early Seattle, is incorrect in several important ways.

Many writers accept that Chin was born in China in 1844 and that he arrived at the lumber mill town of Port Gamble, west of Seattle, in 1862. He is supposed to have lived there for 11 years, learning English, working as a laundryman, cook, and/or regular mill laborer; becoming friends with the family of Chief Seattle and with Henry Yesler, one of Seattle's founders; and saving enough money to bring a wife to the U.S. from China. In 1873, he moved over to Seattle and became a junior partner in the Wa Chong 華昌 company at the invitation of the senior partner, Chin Chun Hock 陳程學, who came from the same place in Taishan county, a hamlet called Langmei 朗美 in the village of Liucun (Luk-choon) 六村. In 1875 or perhaps 1878, his wife delivered a son, Chin Lem, claimed (inaccurately) to be the first Chinese born in Washington State [Note 1].

The main source of this version is Willard Jue [Note 2], a relative of Chin's and a former president of the Chinese Historical Society of the Pacific Northwest, who published an account of Chin's life in the Annals of that organization. At the time, Jue owned the selection of Chin Gee Hee's own papers that is now housed in the Special Collections of the University of Washington Libraries. He based his account on those papers and, acording to his footnotes, on information provided by Margaret Chinn, Chin's granddaughter. It is not clear that Margaret (or Maggie) knew too much about her grandfather who, as noted elsewhere on this website, cut her and her mother off from his family while she was only a girl.

Most later accounts have followed Yue's, including those of Yung, Chang, and Lai (2006) [Note 3] , Doug Chin (2009) [Note 4], and Wikipedia [Note 5.

So. Chin Gee Hee was then known as Ah Ham. He worked as a domestic servant in North San Juan, a California gold mining town about 20 miles up the Yuba River from Marysville, for a number of years previously to his arrival in Seattle. During that time he traveled to China, presumably to be with the wife whom Ms. Brown mentions, and then returned to work for the Browns. All sources agree on the year he arrived in Seattle and became a partner of Chin Chun Hock: 1873.

But Chin Gee Hee's letter of September 1880 says he left the Browns' place "seven years before" the date of writing; that is, in 1873. This did not leave him much time to work in Port Gamble: certainly not the eleven years given by Jue's account. Chin can only have been in Port Gamble for a few months at most. Could a newly arrived Chinese laborer have managed to make friends with prominent people like Chief Seattle and Henry Yesler in such a short time? It is possible but not likely. One suspects a chronological error in this part of the Chin life story. He may have met those men after, not before, his move to Seattle.

We have no reason to doubt that much of the accepted version is true. But the earliest part of his career poses a problem. The Account and Letter Book, which forms the centerpiece of the Chin Gee Hee papers, tells a quite different story [Note 6] .

That story can be extracted from an exchange of letters between Chin and Mrs. John Brown of North San Juan, California. He recopied them himself into the Account and Letter Book [ALB], in which he was collecting important documents of his past, perhaps for his descendants to read or perhaps even for a future biographer. The letters evidently still meant much to him when he put the book together in the early 1900s. For fuller versions of the Brown letters, click here

Young Gee Hee as "Ah Ham" in California

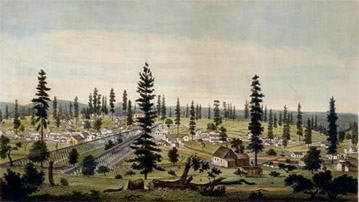

Pope & Talbot Mill, Port Gamble WA, 1880s. From History of the Pacific Northwest, Oregon, and Washington, vol. 2 Portland, 1889. All Chinese were fired from the mill itself in 1877, though a few stayed on as cooks.

North San Juan (CA) in 1858. From a printed poster of which several copies exist; this one is reprod-uced by www.northsanjuan.com. The trestle-like structures on the left are placer miners' flumes