| ||||

Chinese in North America Research Committee

VIOLENCE 排华暴力事件

There is already a large literature on anti-Chinese violence in North America during the 19th and early 20th centuries: an important recent example is Jean Pfaelzer's Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans (2007). We do not propose to recaptulate this literature here, and in any case we feel that Chinese-American historiography is not greatly in need of still more victim narratives. And yet we also feel that modern residents of our liberal, ethnically sensitive, politically correct region must be reminded that the Pacific Northwest has not always been that way. As the following map shows, in the late 19th century our northwstern region was in the forefront of American intolerance and vicious persecution of non-white peoples, especially the Chinese.

The 1886 anti-Chinese riot in Seattle saw many white Seattlites behave shamefully while some, like Judge Thomas Burke, behaved heroically.

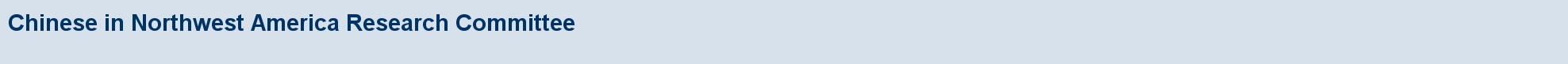

Drawing from Harper's Magazine

Detail of picture on left: The fleeing Chinese,presented as comically wringing their hands and falling down, are protected by Governor Squire's resolute Home Guard, composed of local citizens and University of Washington students

Detail from picture on right. More than half of Seattle's Chinese was forced onto ships before the city government can intervene

All Chinese in Seattle are told they will be expelled from the city the next day. They will be allowed to take only what they can carry. As in Tacoma the year before, actual violence is minimized at this stage, although those refusing are threatened with death. Drawing from West Shore Magazine.

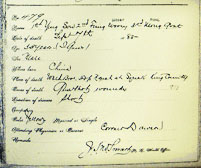

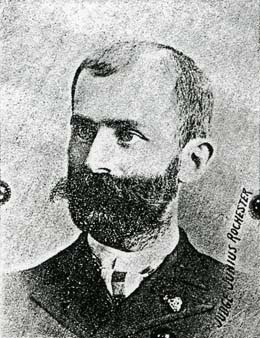

One of the heroes of the day was Judge Thomas Burke, who stood between the angry mob and their would-be Chinese victims with a shotgun (here, a revolver) in his hands. He gave at least three speeches to the mob, saying that he was an Irishman just like them, that he sympathized, and that he was sure they would respect the law unlike the hooligans of Tacoma. West Shore Magazine .

Along with Judge Burke, about 150 armed citizens stood guard to protect the Chinese since February 7.

The Seattle Anti-Chinese Riot, February 1886 西雅图唐人街华人受辱

The attempt to expel all Chinese from Seattle was orchestrated by the Knights of Labor, who hoped to repeat their success at Tacoma in December of the previous year. In Seattle,the attempt was only partially successful. Whereas in Tacoma the mayor and many of the leading citizens had helped in expelling the Chinese, and even took pride in what they called the "Tacoma Solution," Seattle's leaders opposed the idea, partly from principle and partly out of fear of what else a rioting mob might do. These pictures are from Harper's Magazine and West Shore Magazine. In both cases the artist must have worked partly from photographs. (No.16 in the map above).

Judge Burke, two decades later

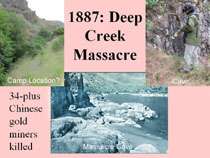

The Deep Creek Massacre, 1887 俄勒冈州蛇河深渊34华人矿工浴血

34 Chinese gold miners were slaughtered by a gang of outlaws at Deep Creek on the Snake River, at the border between Idaho and Oregon. Some of the horror was captured in a letter to the U.S. Secretary of State in February 1888, by the Chinese Minister, Chang Yen Hoon (Pinyin: Chang Yinheng) 張蔭桓. Chang reported that "three bodies of Chea-po's party floating down the river . . ., and upon a search being made further found Chae-po's boat stranded on some rocks in the bar, with holes in the bottom, bearing indications of having been chopped with an axe, and its tie-rope cut and drifting in the water ...; on examining the three bodies found a number of wounds inflicted by an ax and bullets; theat the bodies of theothers that had been murdered have not yet been found ...."

In June 2009, 2010, and 1011, the editors took part in river trips organized by the Historical Museum of St. Gertrude in Cottonwood, Idaho, to visit the massacre site. Several of the participants knew far more about the massacre than we, including Greg Nokes, one of the world's leading researchers on the subject. Those interested should look at Nokes' website, http://www.rgregorynokes.com, and at his book:

R Gregory Nokes, Massacred for Gold, The Chinese in Hells Canyon, Oregon State University Press, 2009

Subsequently, the editors made a case for the idea that a contemporary burst of rebuilding and rededicating the Beuk Aie Taoist Temple in Lewiston 噜士顿北帝庙 , fifty miles downstream from Deep Creek, was meant to commemorate the massacre. Click here for the Memorial for a Massacre article.

A second new book on the massacre has now been published: Dana Hand's Deep Creek: A Novel, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010. Dana Hand is in reality the pen name of a two-person team of well known teacher-writers from Princeton University, Will Howarth and Anne Matthews. For more information, see http://www.dana-hand.com/

There are a number of articles on the massacre and at least one other book (which we have not seen): Mark Highberger, Snake River Massacre, Bear Creek Press, Wallowa, Or., 2000, 48 pages.

Anti-Chinese incidents in the Pacific Northwest: a new map [posted 08/04/10; last updated 07/31/12]

President Taft's list of incidents [posted 10/8/11]

The Anti-Chinese conspirators 1885-1887 [posted 01/20/10]

The trial of the murderers and records of the Chinese victims [posted 01/14/10]

Later Issaquahans minimize the crime [posted 02/20/2012]

Profiting from expulsion: white ladies and teapots [posted 10/18/11]

An honor roll of the victims [posted 02/20/11]

Chinese traders' reaction and Tacoma's defiance [posted 07/08/11, updated 10/17/11]

"Reconciliation" and the Park [posted 02/25/11, updated 10/17/11]

The Tacoma Art Museum sells off collection memorializing the expulsion (posted 03/03/2013)

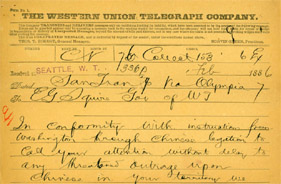

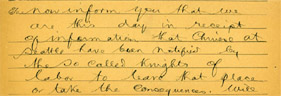

Chinese officials warn Governor Squires [posted 10/10/11]

Woo Gen remembers losing his Chinese business [posted 01/07/10]

Mrs. H. Scovile remembers "buying" a Chinese business [posted 03/10/10]

The Chinese victims [posted 02/14/11]

Mrs. Chin Gee Hee miscarries due to the riot [updated 10/9/11]

Members of the anti-Chinese mob [posted 02/14/11]

Chin Bong remembers [posted 01/07/10]

Ambassador Chang Yen Hoon protests [posted 10/04/10]

New data: Chinese names and home village of the victims [posted 10/5/11]

Finally: the victims' names in Chinese characters. Can their families be found now?:[posted 03/24/17]

Finding Xialiang, the victim's village in China [posted 12/14/11]

The role of Portland's Chinese [posted 10/5/11]

Plans: a memorial for a massacre [updated 11/5/11]

Dedicating the Memorial [posted 06/26/12]

What did Chinatown leaders do to avert violence? Did they succeed? 侨领的贡献[posted 04/06/11]

The Chelan Massacre: The worst incident of anti-Chinese violence in U.S. history [posted 04/21/2013]

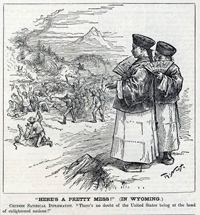

The Rock Springs Massacre, 1885 怀俄明州石泉28华矿工遭毒手

Wikipedia has just produced an excellent brief description of the massacre, its causes, and its consequences. See No. 8 in the map above, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock_Springs_massacre

We will not attempt for now to improve on the Wiki version, which estimates that at least 28 Chinese miners were killed by the rioters on September 2, 1885, in a coal mining area owned by the Union Pacific Railroad in southwestern Wyoming. The Wiki version may be overcautious when it tries to deflect blame from the national Knights of Labor organization. We ourselves see no reason to try to protect the thuggish reputation of the Knights, who were behind so much anti-Chinese violence in the late 19th and even early 20th century.

A few photographs of that part of Wyoming will be

added here in due course. For an image of the massacre

it is hard to beat this picture from Harpers Weekly:

Contrary to the cartoon above which shows two Chinese officials watching over the massacre in a detached way, the Chinese government was very concerned about Rock Sprimgs from the beginning. After much diplomatic haggling, the U.S. Congress paid an indemnity of $147,748.74 in 1887. Zhang Yinheng, the Chinese ambassador who concluded the claim, made this point in his diary.

“the indemnity for the Rock Spring case (洛士丙冷案), compensates only for the property loss but not for the

injustice of the loss of Chinese lives...” “This indemnity was acquired through exhausting the blood in my

heart…”.

.

"Feeling against the Chinese was strong in all northwestern coastal cities at that time, so local residents did not hesitate to pick up arms and turn back a group of about 30 of these foreigners before they even entered the valley. Another larger party had already set up camp at the hop yards, however, and would not leave under threats, so on the next night a posse of five whites and two Indians entered the area and shot up the tents, killing and wounding several Chinese. This strong approach to the situation accomplished the desired result in a hurry, because all the Orientals were gone by the next day. Some half-hearted legal action was later attempted in Seattle against the assailants. but it never came to anything ..."

On September 7 1885, only five days after the massacre at Rock Springs, a group of Washington whites and Indians decided to copy their peers in Wyoming by eliminating Chinese laborers from competition, this time as pickers in the hop fields of the rich Squak Valley, which was then called Gilman and is now Issaquah (see SQ on the map above). How many joined the anti-Chinese mob is unclear: about 10 started out at night from the store of George Tibbets, the local justice of the peace. A few seem to have dropped out while several Indian hop pickers decided to take part and 20-odd onlookers trailed along behind. Everyone had brought guns. The Chinese, who had already put in a day or two of picking in the hop fields of the Wold brothers, were asleep in their tents. There were about 30 Chinese in all.

The Squak (Issaquah) Massacre, 1885

华盛顿州槐花园三华工帐篷遇害

At about 9:30 the group reached the Chinese camp, spread out to surround it on three sides, and opened fire. The tents were riddled with bullets. Those Chinese who were not dead or badly wounded fled across the creek. When they came back 15 minutes later they found the attackers gone, three of their compatriots seriously wounded, and three others dead or dying. The names of the dead were Fung Yue (Fung Wai), Mong Gow (Mock Goat), and Yeng San (Ying Sun). The latter said to Gong Heng San, "I am sorry. Got a son home. Too young. No one to send him money," before he died. Mon Gee and Ah Chow were among the wounded.

Indians Picking Hops on Wold' Brothers Farm

Possible massacre site: between 4th Ave and Issaquah Creek, north of Holly St.

Issaquah Creek at the possible mass-

acre site, south of Juniper St Bridge

Fish's attitude toward his fellow townsmen's atrocity may seem strange, And yet other Issaquahans too continued for decades to minimize or even justify the crime. An example is the account given by Bessie Crane, a lifelong resident of what in 1963 she still called the Squak Valley. Although only three years old at the time of the massacre, she seems to have heard much about it from her parents and neighbors.

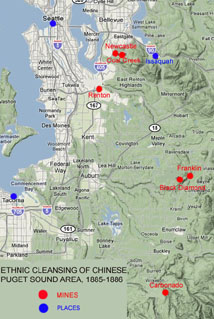

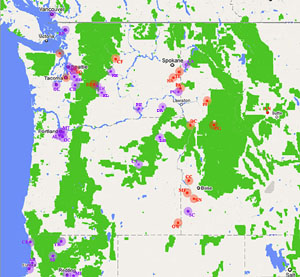

Anti-Chinese Violence, Pacific Northwest (Last revised 10/25/2011)

Incidents shown in red involved killings; those in purple were expulsions, often violent but without recorded deaths. All were at least in part what we now call hate crimes. Crimes committed mainly for profit or personal reasons have been excluded from the list.

1850-1907 美洲西北角发生排华事件地点

-1855 Rogue River, OR. Large party of Chinese miners killed by Indians (The Oriental, quoted by Chung p 47)

-1865-06. Miners of Montana and Idaho bar all Chinese from entering their territories (NYT 1866-06-12)

-1866-06 OW Owyhee River, SE Oregon. 49 Chinese miners killed by Shoshone or Paiute Indians; one boy survives.

-1867-04 SN Undetermined location, Snake River, ID. 62 Chinese killed by Indians (Walla Walla Statesman

-1873. SC Silver City, ID. Labor unions drive out Chinese (Wells, p 43)

-1875. CH Near Methow & Chelan Falls along Columbia River, WA. Indian followers of Chief Moses kill many

-1877 Jackson County, OR. Chinese miners attacked, robbed, and their homes burned. (Chung, p43)

Jackson County, OR. Chinese miners attacked, robbed, and their homes burned. (Chung, p43)

-1878-07 MF Munday’s Ferry, Snake River, ID. 4 Chinese killed by Indians (NYT 1878-08-04, p 1)

-1879. OG Oro Grande, Loon Creek (nr Salmon River), ID. 5 Chinese miners killed. Perhaps by whites, though

-1880 SS Salmon le Sac (Roslyn), WA. 25 Chinese miners massacred (Gaylord p 79)

-1882-04 CC Camas Creek, ID. Three Chinese miners murdered by whites, for gold. (NYT 1882-04-11:1)

-1884. CA Coeur d’Alene, ID mining area. Chinese forbidden to enter “on pain of death.” (NYT-08-04:2)

-1884. PA Palouse River, WA,12 mi. E of Palouse. 3 Chinese miners murdered (Gaylord, p 66)

-1884 SW Swauk (Cle Elum), WA. All Chinese miners expelled Gaylord, p 33).

-1885. BE Bellingham, WA. Chinese expelled. (Bellingham Herald 2003-10-20)

-1885-02 CC Canyon City, OR. Chinatown burned and 1000 Chinese driven out. (Barlow & Richardson, p 12)

-1885-02 EU Eureka, CA. Chinese made to leave in 24 hours, Chinatown destroyed. (Pfaelzer)

-1885-04 AN Anaconda, MT. 5-6 Chinese murdered by explosives placed under cabin (Butte (Montana) Daily Miner,

-1885-06 SQ Squak (Issaquah), WA. 3 Chinese hop pickers murdered & 4 wounded by whites and Indians in Sept.

-1885-07 PI Pierce on Clearwater River, ID. 5 Chinese miners lynched. (NYT 1885-09-23; SF Chron 1886-07-25)

-1885-08 Rock Springs, WY. 怀俄明州石泉28+ Chinese coal miners murdered. (see CINARC website)

-1885-09 CC Newcastle and Coal Creek, WA. Chinese coal miners’ dwellings burnt. (Sacramento Daily Record

1885-09-25: 1)

-1885-10 BD Black Diamond and Franklin, WA. Chinese coal miners expelled on 10/12. (Gov Rept, p 866)

-1885-10 Renton, WA. Chinese coal miners terrorized. (Tacoma News Tribune 1972-02-08, p 2)

-1885-11. Tacoma, WA. Chinese in Tacoma driven out on Nov 3; two-three Chinese die of exposure that night.

-1885-11 Puyallup, WA. Chinese driven out, shortly after those of Tacoma. (Index 1885-6, p 185)

Puyallup, WA. Chinese driven out, shortly after those of Tacoma. (Index 1885-6, p 185)

-1886. MI Millville, CA (E of Redding). Chinese homes and persons attacked. (Pfaelzer, p 270)

-1886. SB Sawyer’s Bar CA (in Siskiyous, N of Weaverville). Chinatown burned; location claimed by whites.

(Pfaelzer p 270)

-1886-01. Redding, CA. Chinatown burned; all Chinese driven out, 01/26. (Pfaelzer, p 270)

-1886-02 CA Carbonado, WA. Chinese expelled on 02/13. (Gov Rept p 866)

-1886-02 OL Olympia, WA. Chinese attacked; many leave for Vancouver BC (NYT 1886-04-12: 2)

-1886-02 OC Oregon City, OR. 40 Chinese robbed and driven out. (NYT 1886-02-23: 2)

-1886-02. Seattle, WA. 西雅图唐人街 Many Chinese forced to leave town; one white rioter killed by militia in Feb.

-1886-03. AL Albina, OR. 180 Chinese woodcutters driven out by masked whites. (NYT 1886-03-02: 1)

-1886-03. AR Arcata, CA. All Chinese purged by end of March (Pfaelzer, p 269)

-1886-03 MT Mt. Tabor, OR. 100 Chinese wood-choppers expelled. (NYT 1886-04-12: 2)

-1886-03. Portland, OR. Chinatown buildings burnt in failed driving out campaign fails 1886. (see CINARC website)

-1886-03 PT Port Townsend, WA. One Chinese attacked & killed. (Chicago Tribune 1886-03-06: 1)

-1886-04 CR Crescent City CA. All Chinese expelled by April (Pfaelzer, p 269)

-1886-08 YR Yreka, CA.. Chinatown burned, 5 Chinese children die, Aug. (Pfaelzer, p 273)

-1886-08 Juneau, AK. 100 whites brutally force a large number of Chinese miners from Douglas Island onto two

Juneau, AK. 100 whites brutally force a large number of Chinese miners from Douglas Island onto two

-1887.  Vancouver, BC. Anti-Chinese riot.

Vancouver, BC. Anti-Chinese riot.

-1887-05 DC Deep Creek, Snake River, OR. 俄勒冈州蛇河 In May, about 34 Chinese miners slaughtered. (Nokes 2009)

-1888. TE Tekoa, WA. Chinese driven out; one lynched for not leaving (Gaylord, p 84-5)

-1890 MA Malden, WA. One Chinese lynched for ignoring "No Chinese Allowed" sign (Gaylord, p 60)

-1891-01 MI Milton, OR. Chinese escorted out of town with ropes around their necks (East Oregonian 1891-01-23)

-1892 DA Dayton, WA. Chinese ordered out at gunpoint; not all go (Gaylord, p 44)

-1892 EL Ellensburg, WA Many Chinese expelled (Ellensburg Daily Record 1989-08-8, 18)

-1892 WE Wenatchee, WA Committee of Six "appointed" to expel Chinese (Gaylord, p 95

-1892 PU Pullman, WA Chinese homes stoned, Chinese told to leave (Gaylord, p 77)

-1892 Bonner's Ferry, ID. All Chinese driven out. (Post-Intelligencer 1892-06-09 & 10)

Bonner's Ferry, ID. All Chinese driven out. (Post-Intelligencer 1892-06-09 & 10)

-1893 LG La Grande & Union, OR. Chinese expelled; 10 local whites indicted, tried, and cleared of any crime. (La

-1895 PS Pascoe, WA. Chinese railroad workers expelled (Gaylord, p 70)

-1905-06 JD John Day, OR. Mob raids Kam Wah Chung store, tells all Chinese in town to leave (letter in KWC Museum)

-1907 VA Vancouver, BC, Anti-Chinese & Japanese riot; much damage and many injuries.

Sources:

Cited newspapers, plus

> Report of the Governor of Washington Territory to the Secretary of the Interior. Gov't Printing Office, 1886

> Papers Relationg to the Foreign Relations of the United States ... December 3, 1888. Gov't Printing Office, 1889

> Index to the Executive Documents of the House of Representatives for the 1st Session of the 49th Congress, 1885-

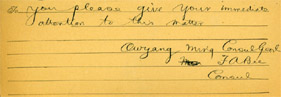

1886, p 197 (Letter from Owyang Ming, Chinese Consul General kin San Francisco)

> Jeffrey Barlow & Christine Richardson, China Doctor of John Day. Binford & Mort, 1979.

> Sue Fawn Chung, In Pursuit of Gold, 2011

> Mary Gaylord, Eastern Washington’s Past, Chinese and other Pioneers 1860-1910. U. S. Dept of Agriculture, 1992.

> R Gregory Nokes, Massacred for Gold, The Chinese in Hells Canyon. Oregon State University Press, 2009

> Jean Pfaelzer, Driven Out: The Forgotten War against Chinese Americans. Random House, 2007

> Fern Coble Trull, The History of the Chinese in Idaho from 1864 to 1910. U. of Oregon MA Thesis, 1946

> Merle G. Wells, Gold Camps and Silver Cities. U of Idaho Press, 2002

> Data on the La Grande expulsions was generously shared with us by Tim Greyhavens (www.what-you-

> CH and SS Although previously doubtful, we are not convinced that the Chelan Massacre actually happened. The

only source we have found for the Salmon le Sac massacre is Mary Gaylord's book. Perhaos some skepticism is

called for in that regard.

Anti-Chinese Violence in the Northwest: New Map & List

| ||||||

版权 Copyright is free for non-profit use: : click here for more information

Portland Tries (and Fails at) Purging All Chinese, March 1886

俄勒岗州钵仑排华无效

Woo Gen's memories of the riot: a 1924 interview

" ... And then when these China riots came I got to give up my business because I cannot sell my cigars. During that time the China riot ruined every Chinaman, including some of the finest residences in Seattle. They have some good citizens in Seattle. I think the big work was done by Mr. Dave Kellog. His brother used to be fire marshall. He get up in the morning and he see this China riot and he went to the fire engine at Columbia Street. He went in and the fire men try to stop him from ringing the bell. He says, "I got orders from my brother." He called all this home guard so the home guard is turn out all over in town and protect the Chinese if he can. The only thing I see in the street I see from my window. I see Mr. William H. White. He was United States Attorney then. He says to the mob, "as long I am prosecuting attorney in this city, you people have to get back to Tacoma." He fight hard. On account of that they didn't drive all the Chinaman out of Seattle. But they did in Tacoma."

"... Judge Burke and Judge Harris said, "... You stay in Seattle. We try to protect all you people as we can. If anyone tries to break your door you just kill him." I get my gun ready and my axe ready and if anyone come, why, I try to kill him. So these mob drove all the other Chinese out from other Chinese houses, but they didn't come near me. I think I am one of the very few to stay here. ..."

Survey of Race Relations [27-183], University of Chicago, July 1924.

Racist elements in Portland attempted to drive all Chinese out of the city in March of 1886, as they had already done in Tacoma and Seattle a month or so before. In Portland the anti-Chinese gangs did not succeed, although many Chinese in and around the city were beaten and robbed. Whether the white citizens of Portland were more tolerant than those of Tacoma and Seattle is debatable. However, the chief Portland newspaper, the Oregonian, followed a generally tolerant line, in sharp contrast with the scurrilously racist Tacoma Ledger. Portland's mayor, John Gates, offered even more of a contrast with Tacoma's mayor, R. Jacob Weisbach. Whereas Weisbach was a ringleader in the anti-Chinese events of October 1885 (and indeed took credit as a deviser of the infamous "Tacoma Solution"), Gates ignored the threats of the mob, reputedly affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan as well as the Knights of Labor, and instructed the police and militia to defend the Chinese, by armed force if necessary.

Chin Bong remembers 1886 in Portland: a 1924 interview

"...Few years after I come, they drive out Chinese out of Portland. When I in Portland, I stayed very close to my store. My store outside Chinese town, in white district, so when they drive Chinese out of Portland, they no touch me, they forget all about I in Portland. But they very cruel, very mean to Chinaman at that time in Portland. And they drive them out. I was glad that I was in American district."

..." Chin Bong, Survey of Race Relations [27-172], University of Chicago, Aug.1924

The result, commemorated by one of Thomas Nast's superb cartoons for Harper's Weekly, was protection for the Chinese and a reputation for fairness and safety that drew many Chinese to Portland over the next decade.

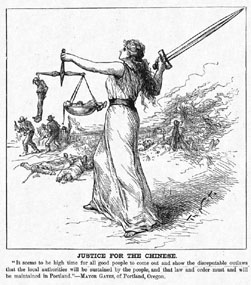

A single death record was prepared for all three Chinese killed at Squak. "Cause of Death: Gunshot Wounds. Duration of Illness: Short" The certificate was made out by King County's Health Officer, based on information supplied by the County Coroner, Dawson. From King County Archives, Seattle

Haskell came to the Congress at the invitation of one of his IWA followers, Daniel Cronin. An official Knights of Labor organizer, Cronin had been involved in the driving-out of Chinese from Eureka in February 1885. The Eureka events, the first of their kind on the continent, became a model for many similar expulsions during the next two years. Cronin was given to citing his experience in Eureka as a credential for his activity in Washington. In September 1885, a few days after the Rock Springs Massacre, he presented a copy of the Knights' anti-Chinese "charter" to Mayor R. Jacob Weisbach of Tacoma, a German immigrant who was already a member of the Knights. Two months later, Weisbach would become a leader in Tacoma's Chinese expulsion, the so-called Tacoma Method. Whether Cronin advised Weisbach during the expulsion is not clear, but Cronin was one of the Seattle-based anti-Chinese leaders who were indicted together with Weisbach and his henchmen by a federal grand jury in Vancouver (Washington). This added to his prestige among delegates to the Anti-Chinese Congress, who hailed him as a martyr to their cause.

Neither Haskell nor Cronin seem to have had a taste for the violence they preached. Haskell went back to California shortly after the Congress ended in mid-February, 1886. Cronin stayed on for a while but, perhaps due to the danger of rearrest, remained behind the scenes during the anti-Chinese riots in Seattle and Portland of March, 1886. In April he was in San Francisco, where he gave a speech at a meeting of the International Workmen's Association and several other labor groups, including the Knights of Labor-affiliated Coast Seamen's Union. In it he revealed that the real target of his activities in the Northwest had been not the Chinese but the capitalist system itself: "There is a greater evil than the Chinese. Although there is not a Chinese at present in the town of Tacoma, the people there have discovered no radical change in the workingmen's condition. It is, therefore, plain that an evil more deep-seated than the Chinese must be sought, namely the present system of labor." (see Chronicle article cited below).

Openly revolutionary rhetoric like this may have displeased Grand Master Powderly, and no one in the Knights can have been happy that their efforts in Seattle, Tacoma, and Portland resulted in repeated intervention by the U.S. Army. Many Knights must also have been angered at Cronin's public admission that competition by Chinese laborers was not such a serious problem after all. Whatever the reason, Powderly soon withdrew Cronin's commission as organizer for the Knights. Cronin disappears from history after that.

Haskell too, by then a vociferous critic and bitter enemy of Powderly, had been forced out of the Coast Seamen's Union and the Knights by 1888. He lost interest in union politics at about that time, allowed the IWA to disintegrate, and for the next five years devoted his energies to a utopian community he had founded in the Sierras, the Kaweah Colony. Whether Kaweah was anti-Chinese, like the contemporary utopian community of Port Angeles in Washington, is not clear. Perhaps Haskell, like Cronin, had discovered that he too did not dislike Chinamen all that much anyway.

Powderly, less mercurial in temperament and more steadfast in his hatreds, was appointed Commissioner General of Immigration by President McKinley in 1897. Continuing to work at the Bureau of Immigration until 1921 gave him ample scope to become one of the worst enemies that Chinese in the United States would ever know.

On Haskell Kevin Star, Endangered dreams: the Great Depression in California, 1996; Craig Phelan, Grand Master Workman: Terence Powderly and the Knights of Labor, 2000; Miriam Allen De Ford, They Were San Franciscans, 1941; New York Times 1886-02-12 p 5, 1886-02-13, p 1, 1886-02-14 p2; for Haskell in Eureka, Jean Pfaelzer, Driven Out, 2008, pp 14-7

On Cronin -- Wikipedia; Carlos A Schwantes, "Protest in a Promised Land: Unemployment, Disinheritance, and the Origin of Labor Militancy in the Pacific Northwest, 1885-1886;" The Western Historical Quarterly, Vol. 13, No. 4. (Oct., 1982), pp. 373-390; C. J. Lind, The Chinese Must Go," Tacoma News-Tribune, 1972-02-08; San Francisco Chronicle 1886-04-11 p 10

Note: the editors were not aware at the time of writing of Marie Wong's discussion of Haskell and Cronin in her book, Sweet Cakes nd Long Journey, the Chinatowns of Portland, Oregon (2004, pp 45-47). Her conclusions are similar to ours --- 07/02/2010..

The Anti-Chinese Conspirators 煽动排华主谋人

Considering that so much violence against Chinese occurred in so many parts of California and the Northwest during the years 1875-1877, anyone would think that there was a connection -- that the similarity of scenarios and speeches by anti-Chinese elements points to central planning and control. But who were these planners? The obvious candidates are the leaders of the Knights of Labor, an organization with a strongly racist ideology and the influence, size, and geographic reach needed to pull such a conspiracy off.

The only problem with such a theory is the Knights' long-standing distaste for actual violence. Grand Master Workman Terence Powdermaker, the leader of the Knights, was strongly opposed to the dynamite-throwing favored by radical socialists and nihilists. Most authorities agree that he was effective in suppressing the violent tendencies of his more extreme followers.

But then how to explain the many riots, killings, and drivings-out of the Chinese in 1885-1887?. One explanation is that they were planned by a secretive, violent extremist group, the International Workingmen's Association, operating within the larger Knights of Labor. The West Coast (and only active American) branch of the IWA, originally British, was founded by one Burnette Haskell, a California lawyer. He set it up as a series of cells, much like those favored by European radicals, and seems to have maintained a high level of internal secrecy. Curiously, in view of the internationalist ideology of his movement, he adopted the anti-Chinese stance of rank-and-file members of the Knights. In 1883-84 he organized a IWA affiliate in Eureka, where it played a key role in driving out Chinese in February, 1885. In February, 1886 he appeared as a leader at the Knights of Labor's Anti-Chinese Congress in Portland, where he was acclaimed as the Chairman of the key Committee on Resolutions and gave interviews to the press describing how Chinese would soon be driven out of Portland.

Burnette Haskell

Terence V Powderly

"Anaconda Letter: Four Chinamen Blown into Eternity (04-16, p 4)

"Following upon the heels of this __ event was one of the most dastardly, diabolic and successful attempts upon human life ever made in Montana. A little after __ o'clock a loud explosion startled the whole town. This was followed in four or five minutes by another, still louder and, as it proved, more destructive in its character. The place was now thoroughly aroused and men flocked from every direction to the point __ which the explosions __ __. Your correspondent was among the first upon the ground. A heart sickening scene presented itself. Two dead Chinamen blown out of shape and beyond recognition, another in the agonies of death, a fourth mortally wounded, and four others more of less wounded were lying among the logs and debris of a completely demolished building.

"The facts as I gathered them are as follows. The building which was situated on front street two blocks below Main was used as a wash house, and at the time of the explosion contained eight Chinamen.

"Some FIEND OF FIENDS in human shape had placed two sticks of giant powder [a dynamite-like high explosive – eds.] under the building—one near its front and the other near its rear. The fuses to each were cut at different lengths, the one near the rear of the structure being the shorter. At this end of the building a Chinaman was over the tub washing clothes. At the first explosion the unfortunate heathen was blown out and struck the ground dead. The others were sleeping in the front room of the building. One of them immediately arose and struck a match. He had just lighted a lamp when the second explosion occurred, killing him and wounding the others as above noted. Drs. Gleason and Hardenbrook who were soon upon the ground took one of the poor unfortunates into an adjoining building and, while they were dressing his wounds, his spirit took its everlasting flight to the boson of Confucius. Another of the victims is probably dead by this time while two others may live a day or two longer.

"CORONER M ____ came up from Deer Lodge on the evening train to hold an inquest upon the remains of the dead Chinamen, At this writing, the verdict of the jury is not known. But it is questionable whether any facts will be elicited which may lead to the apprehension of the perpetrators of this most dastardly and unprovoked murder. The building and the one adjoining it, which is also run by Chinamen, are owned by Joe Loong. The restaurant was not injured.

"A narrow alley separates these buildings from a fine large brick structure owned by Mr. Quigley. This building is used as a saloon. At the time of the explosion a __ lively stud poker game was running in it and several men were leaning __ the bar. The shock broke every glass in the double door and front windows. The inmates instead __ running out __ __ the rear __ __. this act doubtless saved the lived of many of them. Had they run out and back to the alley when the second explosion took place a larger death toll would be recorded. [1½ more paragraphs; unintelligible]"

"Anaconda Explosion (04-17,p 4)

"Since the letter of yesterday morning, published in the Miner, no new facts have been developed in regard to the cause of the explosion in Anaconda. There are several theories concerning the affair—one that the deed was done by friends of two men who were sent to the country jail recently for breaking into the house which was blowing up, pillaging it, throwing beer kegs through the window, and beating one of the inmates unmercifully. Another theory is that the place was an opium joint, and that one or two young white girls had been induced to enter it; that while there they were persuaded into smoking opium, and that other and greater evils resulted; that it was for this reason that the place was blown up. There is no positive evidence in regard to either of these theories, and the last one mentioned seems hardly probable, as the Chinamen could not but know that such an act in Montana would surely result in their death. Parties who were in Anaconda since the explosion say the men killed were horribly mangled and that the two men yet living are expected to die. As first they were not supposed to be much hurt, as no wounds were apparent, but it has since been ascertained that they are seriously injured internally."

The Anaconda Explosions, April 1885: The First Organized Labor Murders or Private Revenge? 蒙大拿州阿纳孔达五華工遇害-是谋杀?是报复?

The following two articles appeared in the Butte (Montana) Daily Miner on April 16 and 17, 1885. By far the most complete descriptions of the explosions, they have not been republished since 1885. The only available on-line images of the newspaper, made from bad microfilms, are very difficult to read. Anaconda, incidentally, is about 30 miles from Butte.

The great smelter smoke stack at Anaconda, said to be the tallest free-standing masonry structure in the world, surrounded by slag and mining debris. Built in 1911, the stack postdates the Chinese period at Anaconda. Photo from Wikipedia Commons

Were the killings connected with organized labor's anti-Chinese movement, which was already active in much of the West? Possibly. The early stages of the West Coast anti-Chinese campaign were widely reported in Montana, and five months later, the local Knights of Labor ordered all Chinese to leave Butte and Anaconda by October 1. Those in Anaconda left immediately, although at least some of those in Butte stayed. Chinese cooks and waiters in Anaconda were all replaced by Knights (New York Times 1885-09-21, p 1; 1885-11-07, p 3 )

Most newspapers mention a detail that was skipped by the Miner: that the murderers were professional wood choppers, producing firewood for sale. There had been previous trouble between white and Chinese wood choppers. In 1881, according to the Helena (MT) Daily Independent (1881-12-20), "a band of over a hundred Chinamen were chopping wood near Blacktail gulch at seventy-five cents per cord. This was less than half the price charged by the whites. It was understood that on Saturday about one hundred wood-choppers near Butte banded together and started for the Chinese camp with the avowed purpose of 'seeing it out.' " Hence, it seems possible that labor issues did play a role in the killings, although personal motives seem also to have been involved.

A later article by the Times (1901-07-10, p 1) states that the Chinese government was seeking compensation for the killing and expulsion of Chinese that took place in Butte in 1886. Those killings may actually have been those that occurred at Anaconda in April, 1885.

That a total of four Chinese were killed at Anaconda is confirmed by no less an authority than William Howard Taft, former President of the United States and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. See W. H. Taft, "The Unprotected Alien and our National Responsibility," The Independent, vol 77, p 204

The Chinese were not all driven out of Butte. They stayed until the 1970s or 80s, producing both the noted Chinese-American historian, Rose Hum Lee, and also a Chinatown that included this building, now the home of the Mai Wah Museum.

The story was picked up in brief notices by a number of national and regional newspapers, including the New York Sun (1885-04-17, p 2); the San Francisco Chronicle (1885-04-21, p 3), the Maysville (KY) Daily Evening Bulletin (1885-04-18, p 1), and the Syracuse (NY) Standard (1885-04-19, p 2). The New York Times, on the other hand, did not pay attention until September 1886, when the Chinese government claimed indemnity for the killings (1886-09-04, p 5). Interestingly, the Times stated that only two Chinese laundrymen were killed.

The non-Montana newspapers seem to have accepted the theory that the attackers were seeking revenge for their imprisonment, paying no attention to the Daily Miner's enticingly racist fantasy about white girls lured into smoking opium and experiencing "other and greater evils."

Coal and Ethnic Cleansing: Driving Chinese from Washington's Mines

华盛顿州煤矿工会组织排华运动

Coal was a more dangerous ethnic flashpoint than was gold during the driving-out years in the Pacific Northwest, 1885 and 1886. For one thing, coal was of much more interest to the Knight of Labor. Coal mines tended to be bigger than gold mines, to employ more men, and to be owned and run by big-city corporations, all of which made them optimal targets for organizing by labor unions. From the 1880s onward, the owners/managers of such mines regularly sought to hire Chinese. Just as regularly, the unions objected, often violently. Wyoming's Rock Creek Massacre, supported by (and probably organized by elements within) the Knights of Labor, featured white and Chinese coal miners employed by the mining division of the Union Pacific Railroad.

In Washington State too, much anti-Chinese violence in 1885 and 1886 was coal mine-related. All of it took place at mines in the Pacific Coal Region of Washington State, on the western flanks of the Cascades: at Coal Creek, Newcastle, Renton, Black Diamond, Franklin, and Carbonado. Together with coalmines at Nanaimo and Cumberland on Vancouver Island, those Washington mines fueled most steam ships on the West Coast, as well as the majority of railroad locomotives and coal gas plants west of the Sierras and Cascades

It is interesting to note that that Coal Creek and Issaquah, the site of the Squak Massacre, are on opposite sides of Cougar Mountain and less than five miles apart. The first attacks on Chinese miners at Coal Creek and Newcastle, one mile further downhill, were made on September 11, four days after the Squak shootings of September 7. Whether any of the same people were involved is unclear [but now it is quite clear--click here for article], but there can be no doubt that whites and Chinese at Coal Creek-Newcastle were intimately familiar with the Squak events.

The Coal Creek-Newcastle attack was carried out by heavily armed, masked

white men: “They came to the place where he [Robert Wood, a white employee of the mine who became a witness for the government] was at work and took hold of a Chinaman employed there and took him away with them towards the house, which was soon thereafter destroyed. Violence was used against the Chinese, and one of them was choked by a person in a mask.” [Note 1] . Chin Poy Hug was one of the victims who were forced out of the house before it was set on fire. Chin Gee Hee 陈宜禧of Wa Chong & Co, who was the Chinese labor contractor for Coal Creek, made a claim of loss for $1,506.

By September 29, according to the New York Times, all Chinese workers at coal mines in the Coal Creek-Newcastle-Renton area had been discharged. The cause was threats against both Chinese and mine owners. On the same day, delegates from several mining areas, including Renton, Black Diamond, Newcastle. and—perhaps significantly—Squak/Issaquah attended a widely publicized anti-Chinese meeting in Seattle, sponsored by the Knights of Labor. [Note 2]

On October 12, "strong efforts" were made to intimidate Chinese employed at the Franklin (and presumably the neighboring Black Diamond) coal mines. At Franklin, a building from which the Chinese had been expelled was burned. [Note 3]

By February 13, 1886, the expulsion gangs having moved further south, Chinese had also been driven from the Southern Paciifc Railroad's coal mines at Carbonado.

Chinese coal sorters at Newcastle Mine, Washington, 1884

Note 1: "Report of the Governor of Washington Territory," in Report of the

Secretary of the Interior for ... 1886. Washington: Government Printing

Office, 1886, Vol II, pp 52, 901, 911

Note 2: New York Times 1885-09-30, p 1; Sacramento Record-Union 1885-09-24 p 1

Note 3: "Governor's Report" 1886, p 866.

Note 4 Squire to Endicott, Sec''y of War. "Governor's Report" 1886: p 859

For a summary of the coal-related geology of western Washington, see http://www.washington.edu/uwired/outreach/cspn/Website/Course%20Index/Lessons/15/15.html

The Newcastle mine picture is from Ernest Ingersoll, "From the Fraser to the Columbia," Harper's Monthly, May 1884, p 875

It is usual to consider that the killing of the Squak hop-pickers was an isolated rural event, with local causes and, in spite of the Chinese-depriving-us-of-jobs rhetoric used, unconnected with the contemporary anti-Chinese campaign of the Knights of Labor. Most historians have discounted the idea of a connection even though the expulsion of Chinese from Coal Creek, unquestionably carried out by the Knights, happened only five days after the Squak Massacre and only five miles away.

Now, however, there is direct evidence of a connection. The following article appeared in the anti-Chinese and pro-labor Sacramento Daily Record-Union on September 11, 1885, the same day as the Coal Creek events.

"The Attack on the Chinese Hop-Pickers

"Seattle, September 10th -- Five white men--Percy Bayne, Sam Robertson, Jos. Day, M. D.Rumsey, and D. W. Hughes--and two Indians were arrested and brought to this city this morning, charged with conspiracy in the massacre of the Chinese at Squak. It appears that a regular conspiracy had been formed to drive the Chinese from Squak Valley. The plan was first to visit the Chinese camp at the mines and Coal Creek, and then to attack those in the hop field. This plan partially failed through the weakening of some of the conspirators, and the hop-pickers' camp only was attacked..." (Record-Union, 1885-09-11, p 4)

Though based far away in California, the newspaper seems to have had excellent sources in Washington. Its staff may have known in advance that another attack on Coal Creek was planned for the day the above article was published.

Mrs. H. Scovile's memories of the riot: a 1938 interview

"What I remember best about the early days in Seattle in the Chinese riots in 1886.

"My husband came home one Sunday morning and told me an officer from the Home Guards had come into the church and commanded all the men to report for duty at once.

"There were a number of Chinese in Seattle then, some running laundries, others having cigar stores, and so on. The people of the town had become incensed at the idea of Orientals being allowed to carry on business when Americans needed work.

"The Committee of Fifteen had told the Chinese that they must go, get out of town, by a certain date. A steamer from San Francisco would be in the harbor on that date, and they must go aboard.

"The Chinese began selling off their goods and equipment. My husband and I decided to buy a laundry. We knew nothing about the laundry business but we thought we could learn.

"We bought the laundry and all the equipment for almost nothing, and opened for business. We prospered, the business grew fast, and we never regretted buying a laundry at a bargain sale."

Mrs. Scovile, described as "an English type; stoutish, round-faced, rosy complexion. Interested in everything going on," was interviewed by Verna L. Stamolis as part of a WPA project. Mrs. Scovile seems to have remembered her takeover of a Chinese business as just luck on her and her husband's part. However, they would have had to move fast to choose a particular laundry and then "buy" it from the owner as he left, on one or two days' notice. The Scoviles may well have joined in driving the owner out.

Library of Congress American Memory files, http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?wpa:5:./temp/~ammem_gggc::

The Connection between the Squak Massacre and the Coal Creek Expulsion 华盛顿州槐花园与煤矿渊两地暴力排华的渊源

Ford Slope entrance of Coal Creek mine, ca. 1910

Rebuilt mining car at Coal Creek, ca. 1890

The Chinese left Coal Creek after the September 11 attack (see http://www.cinarc.org/Violence.html#anchor_173) However, as this sign in the present-day Cougar Mountain Park in Coal Creek shows, their former presence has not been entirely forgotten.

Click on map to enlarge

Click on map to enlarge

The outbreak of anti-Chinese violence in 1885 and 1886 had been politically motivated. Much of it was organized by loose groupings of labor unions under the leadership of the Knights of Labor. The Deep Creek Massacre, by contrast, seems to have been motivated chiefly by a desire for gold, although the events of 1885-6 undoubtedly helped to convince the perpetrators that they could get away with it. (See map above - 1887-05).

Ambassador Chang Yen Hoon Protests 驻美公使張蔭桓的第一反应

In February 1888, the Chinese Legation in Washington DC felt it had enough information about the massacre to lodge a formal protest with the U. S. State Department. A copy of the protest is included here for those interested in seeing evidence that the imperial government was well-informed about events in the U. S. and that it consistently tried to protect its overseas citizens. This contradicts claims of anti-Chinese writers that the rulers of China were indifferent to the sufferings of their overseas countrymen.

Chang Yen Hoon's letter of protest includes certain details that are included by Greg Nokes in his Massacred for Gold book, including the names of some of the local Chinese who testified about the killings and their aftermath. To view the letter, click here.

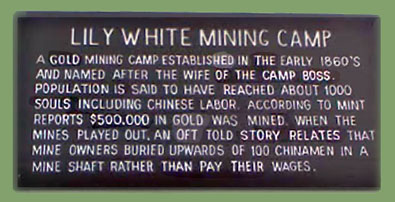

Myths of Violence: Lily White

Legends about killings of Chinese can be a problem. Many are wildly implausible. We have been told, for instance, of burials of murdered Chinese workers next to railroad tracks deep beneath an Ontario lake, in an area where no Chinese ever laid track and where the lake existed in its present form long before the arrival of either trains or Chinese.

Why worry about such absurdities? Because of why non-Chinese so often feel that legends of this kind are believable: because they are told that in China, in the past, life was cheap, and that Chinese North Americans were invisible to and ignored not only by white lawmen but also by the Chinese government and even by other Chinese immigrants. The belief that no one cared about Chinese can still be found among European North Americans. It was formerly accepted by numerous white Northwesterners and helps to explain why so many white thugs, not to mention stone-throwing white children, felt that violence against local Chinese could be indulged in without consequences.

It is easy to dismiss the legend of the railroad at the bottom of the Ontario lake. Other legends, set in a more credible historical context, cannot be so readily dismissed without further study. There are many such legends, and most turn out on examination to be unprovable or entirely mythical. One example, that of Oregon's Lily White mine, is discussed here. The main myth-buster in this case is Dr. Priscilla Wegars, the founder of the Asian American Comparativer Collection at the University of Idaho in Moscow, with a comment by Dr. Chuimei Ho, co-editor of the Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee.

From Steve Wood, Walla Walla, September 22. 2009

Over 30 years ago there was a National Forest history sign in the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest up out of Medical Springs, Oregon that detailed a Chinese Labor Massacre at the Lily Creek Mine. It stated that over 300 Chinese Labors were herded into the mine and then it was blown up. The sign was removed by the Forest Service over 20 years ago. Can you shed any light on this dark event?

From Priscilla Wegars, Asian American Comparative Collection, Moscow, ID, November 26, 2010

I saw [the above] post in the Comments section of the CINARC Web site. The following is from a slide talk on the Chinese in northeastern Oregon that I presented in 2003:

One thing that historians and archaeologists do is to try to separate myth from reality. For example, a site on the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest, at Lily White, has recently been the subject of some controversy. A former Forest Service interpretive sign there stated, in part, that "an oft told story relates that mine owners buried upwards of 100 Chinamen (I see that the number has now inflated to 300, above!) in a mine shaft rather than pay their wages."

Such "Chinese massacre" legends are common in mining country where the Chinese are known to have worked. It is true that many Chinese in the West were badly treated, and it is also true that some were murdered by Caucasians. However, unlike the 1887 Snake River massacre, for which ample newspaper and other documentation exists, the supposed Lily White incident has no basis in fact, and so far, no Chinese are known to have worked as lode miners in the vicinity.

You will notice that, near the end, this sign uses the word "Chinamen." In the past, that word was often used by Caucasians in a derogatory way when speaking of the Chinese. Today that word is best not used, because it recalls those days of anti-Chinese prejudice. The term "Chinese person" is a better choice. The sign has now been replaced with a different one, and no longer contains the word, "Chinamen."

If the Lily White massacre did happen, then where is the corroborating information? Any of the following would help verify the legend:

1. newspaper accounts of the slayings, or

2. census records for Chinese at Lily White, or

3. any documentation for Chinese lode miners at Lily White (Chinese lode miners were extremely rare

4. archaeological remains of the large Chinese living camp that would have been associated with such a

5. records of investigations by the Chinese government, which would have been conducted if 100 Chinese

6. the 100 skeletons.

Here's a YouTube video that shows the old sign and has some people singing a song about the legend:

I didn't watch/listen to the video but part of the "legend" supposedly states that at the full moon the ghosts come out of the mine to sing and dance.

Richard Harris of Baker City, Oregon, believed strongly in the legend. He offered $10,000 to anyone who could prove it. No takers. He wasn't interested in my evidence, above, for their NOT being such a massacre.

He ended up spending his $10,000 for a pavilion imported from China and placed in the Baker City Chinese Cemetery.

You can see the pavilion here:

It was a nice gesture, but was it an appropriate addition to the historic Baker City Chinese Cemetery? Just asking.

From Chuimei Ho, CINARC, Bainbridge Island. WA, December 2, 2010

The way we heard it, the Chinese were not miners but ditch/canal diggers, who were forced into the Lily White mine and murdered so that the mine owner would not have to pay them for the job they had just completed. But I agree that the story is almost certainly a myth.

To my mind, the decisive piece of evidence is the non-reaction by the Chinese government and the relevant Chinese regional and family name associations, not to mention the Chinese labor contractors who would have hired them. It is not at all true that no one in the American Chinese community was keeping track of miners and others in the interior West. After the mid-1860s, when telegraph lines and more or less passable roads and trails had reached most parts of the interior, it would have been impossible for any group of people, whether Chinese or white, to have vanished without anyone commenting on it.

You're quite right about the relevance of the Deep Creek massacre. In that case, the reaction of Chinese in Lewiston and San Francisco was quick and commented upon repeatedly by the white media. The disappearance of a hundred plus Chinese at the Lily White mine would surely have been noticed.

Another myth, we think, is the supposed massacre of 25 Chinese gold miners at Salmon le Sac near Roslyn, Washington, in 1880. [Mary Gayford mentions it without references on page 79 of her generally accurate Eastern Washington's Past: Chinese and Other Pioneers] As in the case of Deep Creek / Snake River, the disappearance of so many, even in an area as virulently anti-Chinese as Roslyn-Cle Elum, could not possibly have escaped notice by the regional Chinese community and the white media.

Would you let us put your email onto the CINARC website? Letting more people read it might help to put the legend to rest.

From Priscilla Wegars, AACC, Moscow, December 2, 2010

It is interesting how the story becomes embellished in the retelling. There were Chinese ditch diggers in eastern Oregon but they would not have been needed for a lode (underground) mine. (You probably know that Chinese dug the El Dorado Ditch and the Sparta Ditch in eastern Oregon.)

You probably also know (but in case you don't) that a placer mine is above ground and needs water to wash the dirt and gravel to recover the gold flakes and nuggets; the water is brought from the nearest creek via a ditch system. A lode (underground) mine doesn't use water because the gold is contained in quartz rock (ore) which must be brought up to the surface in an ore cart (on rails) and taken to an ore crusher of some sort - often an arrastra (huge grinding stones) or a stamp mill (metal weights that crush the ore).

So if the deceased Chinese were thrown down the mine shaft, it would have been a lode mine and therefore doesn't follow that the mine owner would have hired them to dig ditches.

I have never heard about the supposed Salmon le Sac massacre but it, too, sounds dubious for the reasons you suggest.

Sure, you can add my email to your comments section (or wherever you want.)

I love myth-busting!

Former Forest Service sign, Wallowa-Whitman National Forest, Oregon

Mrs. Chin Gee Hee miscarries three days after the riot 陈宜禧夫人早产

"During the riotous proceedings the residence of Mr. Chan Yee He [Chen Yixi] was invaded by the mob and his wife was dragged downstairs from the second story and out on the street by the hair of her head. The fright and bodily injuries received made her seriously ill, and three days afterwards she was prematurely delivered of a child. After a long sickness and intense pain for several months she finally recovered her health... ."

Quotation from Mr. Chang Yen Hoon's [Engliosh-language] letter to Mr. Bayard, Washington, March 3, 1888, in Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Part I. 1889. No. 254, pp.389-90.

"Chin Gee Hee's wife was pregnant, and because of the disturbanceas she fell from the second floor. Three days afterward she had a miscarriage. I have not mentioned this detail to Bayard before, Now I willl bering it up."

Quotation from: Zhang Yinhuan's (Chang Yen Hoon's) published [Chinese language] diary, Sanzhou Riji,1896.

The anti-Chinese mob - who were they? 西雅图排华主谋

List of persons kept by Provost Marshal K.E. Alden, who were arrested during

martial law in Seattle, February 10-17, 1886.

- W. H. Pinckney. A Seattle policeman, was arrested on February 14 for "dereliction of duty as police officer and affiliating with the mob." He appears to have lost his job as in 1890 he went to Blaine and opened a real estate office in the Steaubli building. But he joined the police force there in 1905 as a wharfinger, a position appointed by the mayor and confirmed by the city council.

- J. T. Winscott. Arrested on February 14 for being a "prominent Chinese agitator using incendiary language."

- Louis R. Kidd. Arrested on Feb 16 for being a"prominent agitator leader in forcibly on ejecting chinamen on Sunday 7th inst.and using loud and treasonable language since the declaration of martial law."

Extracts from the diary of Chang Yen Hoon, Chinese Minister 張蔭桓日记

May 2, 1886. The new Chinese Minister (Ambassador), who had barely arrived in the U.S. for a month, received a cable directly from Chin Gee Hee in Seattle, reporting that the Federal troop was about to leave but the local Seattlites were still plotting to expel the Chinese residents there.

May 4, 1886. Cabled to Wah Chong [i.e. Chin Gee Hee's company in Seattle], regarding Federal troop's postponed departure, copy sent to the San Francisco Consulate.

Sept 26, 1886. Reporting from Yao Zhupeng that the Federal troops left Seattle in August and now only several tens of Chinese stayed in Seattle. [212 of the Seattle Chinese landed in San Francisco on February 11 on steamship Queen of the Pacific].

Oct 8, 1886. Correspondence from the Chinese community in Seattle reporting that the arrested ring leaders were discharged .... Will follow up with Bayard [the Secretary of State] when he returns.

March 3, 1888, Bayard cited Chin Gee Hee's case as an example of over-claiming compensation. Explained to him that my letter focused on the sufferings of the victims...Source: Sanzhou Riji [Three Continents Diary], by Zhang Yinhuan [Chang Yen Hoon] 1896.

- Junius Rochester. A lawyer from a well-known family, he was arrested on Feb 17 for being a "prominent agitator leader in expelling chinamen forcibly on the morning of Sunday 7th inst.and using loud and treasonable language since the declaration of martial law."

- John Keane. Arrested on Feb 17 for being a "prominent agitator and leader in expelling chinamen forcibly on the morning of Sunday 7th inst. and using loud and treasonable language since the declaration of martial law." Said, when arrested, "This is poor coin to be paid in for all my work in preserving the peace."

Junius Rochester

- William Murphy. Chief of Police in Seattle, was arrested on February 12 for being also "a leader in Chinese agitation." He nonetheless was re-elected in July 1886 and 1887 to the same position. In 1900 he was elected 9th ward councilman, a position he held until 1911.

- George Venable Smith. A Seattle city attorney who was arrested on February 13 for being "a leader in Chinese agitation." He was one of the founders of the utopian Puget Sound Cooperative Colony that in 1887 developed Port Angeles to be a Chinese-free city.

The Chinese Victims - Who Were They? 西雅图受害者名单

Among the 350 rounded-up Chinese residents, some worked for these laundries:

some worked for these restaurants:

Foo Kee, Hong Fong Low, Gim Lee, Jake Lee, Moy Foy,

some worked for these groceries or import-exporters:

other individuals:

Mrs. Chin Toy and her 4-year old son Chin Shug, 陈灼, Chin Kee, Jimmy Gon Gan (a

Sources: Willard G. Jue Papers, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collection; Seattle City Directory, 1887; NARA Archive RS 26312 "Chin Shug", RS 17422 "Kie Qua".

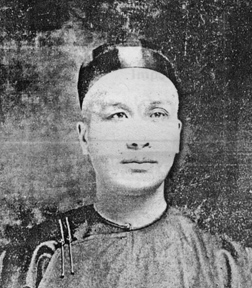

Chang Yen Hoon, Chinese Minister. 驻美公使張蔭桓

Chin Shug in 1900

Chin Kee in 1901

G. Venable Smith

Some were jailed for a few days and then discharged on a $1000 bond. While a few were were indicted by a grand jury, none were ever convicted. G. Venable Smith was disbarred.

Other anti-Chinese leaders are mentioned by Roger Sale in his Seattle, Past and Present (1976). The book is a credible source because its author, a University of Washington professor, sympathized with the anti-Chinese movement. As shown by writings of Issaquahans and Tacomans in the 1930s, such sentiments were common enough before World War II. Many Washingtonians probably still felt that way in the 1970s, but few except Sale seem to have said so in print. Sale was sharply critical of the extreme pro-Chinese "Law and Order people," including David Kenny and those who displayed the "moral arrogance of George Kinnear, R.S. Greene, and Cornelius Hansford," not to mention "the pugnacious obtuseness of Thomas Burke." He wrote approvingly of such "sensible" individuals as Sheriff John McGraw, J. C. Haines, John Keane, G. Venable Smith, and Mary Kenworthy -- people who "were artisans and bourgeois, not themselves threatened by coolie labor, but caring nonetheless" about the (In Sale's eyes, justifiable) anger of white workers faced with Chinese competition. [Sales 1976: 47-48

Hence, we may reasonably add Haines and Kenworthy to the roster of the anti-Chinese mob although they are not mentioned by Provost Marshal Alden. And, of course, we must not forget the professional agitators sent to Seattle by the Knights of Labor -- Daniel Cronin and, according to Sale, James McMillan.

Mary Kenworthy, "a fiery, resolute Seattle widow" and also a noted Socialist and suffragette, is thought to have been the main drafter of the resolutions passed by Seattle's Anti-Chinese Congress in the fall of 1885. She not only saw Chinese competition with white workers as "threats to homes, families, decency, and morality" but went so far as to 'organize [white] women to go around house to house insisting that all Chinese domestic help be let go." (Sale 1976: p 41)

Sources: University of Washington Libraries, Digital Collection.

Report of the governor of Washington territory, made to the secretary of the Interior 1886 .

What Did Chinatown Leaders Do to Avert Anti-Chinese Violence? Did They Succeed? 侨领对保护华侨的贡献

It is noteworthy that certain cities and regions suffered less than others during the years of violent anti-Chinese agitation in the late 19th century. The Boise Basin in southern Idaho and most of British Columbia were examples. Others were Chicago and New York. So were Portland, Oregon and, in the 20th century, Seattle.

Another example is Seattle. In 1886, Chin Gee Hee's close business connections with such figures as Judge Thomas Burke, along with his influence at the Chinese ministry in Washington, was a key factor in persuading the white establishment to intervene against attempts to drive out Chinese residents [Note 6]. Goon Dip, 阮洽. one of Chin Gee Hee's successors as leader of the Seattle Chinese community, played a similar role in the early 1900s. Goon's friendship with J. A. Chilberg, important businessman and president of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, is mentioned elsewhere on this website. In Chilberg's words, "We [Goon and I] became great and good friends until his passing, and to him I am indebted for most of my knowledge of Confucius and his teachings." [Note 7]

---------------------------------------------

Image Credits: The photo of Goon Dip is by courtesy of Steve Goon of Seattle. The drawings of Moy Back Hin and Chin Gee Hee are from the International Chinese Directory for 1901 (San Francisco: Chinese Ditrectory Co.), loaned to us by Phil Choy of San Francisco, The drawing of Wu Ting Fang is from the San Francisco Chronicle 1895-04-02. The drawing of Wong Chin Foo is from the 1877-05-26 issue of Harper's Weekly.

Note 1. Even-handed courts: see Liping Zhu, Chinaman's Chance, 1997, pp 134-146; for the role of the Idaho and Chin Gee Hee Supreme Court, see also the permanent Chinese exhibit in the Idaho State Historical Museum,

Note 2. Chinese just one among many ethnic immigrants: interview with Moy Dong Chew, printed by Tin-Chiu Fan, Chinese Residents of Chicago, 1926 MA Thesis, U. of Chicago

Note 3. Chin Foin and Chicago bosses: see http://www.ccamuseum.org/Research-2.html#anchor_139

Note 4. Wong Chin Foo and Tom Lee: for relevant news stories, see ProQuest's on-line historical New York Times--for example Lee's and Wong's banquet for city officials in NYT 1888-09-14, p 5

Note 5. Moy Back Hin and Seid Back: See Marie Rose Wong, Sweet Cakes, Long Journey, 2004, pp 175-197. Moy's close relations with Justice Matthew Deady. mentioned by Wong, parallels the Chin-Burke connection.

Note 6. Chin Gee Hee and Thomas Burke: For their friendship, see the unpublished Willard Jue Papers, University of Washington Library

Note 7. Goon Dip and Chilberg: see this website, http://www.cinarc.org/AYPE.html#anchor_165

Note 8. Goon Dip in Wu Chang's report: Academia Sinica Archives, 03-12-003-05-013, Taiwan

Note 9. Goon Dip and Ella McBride: Willard G Jue and Silas G Yue, "Goon Dip: Entrepreneur, Diplomat, and Community Leader," Chinese Historical Society of the Pacific Northwest, ca. 1990

Goon Dip, ca. 1905.

Community leaders in Portland, Victoria, and Vancouver, and later in Seattle too, seem to have built bridges more often and effectively. Coming from the same backgrounds as their East Coast counterparts, with only modest educations but much experience in buying from and selling to European-Americans, the fact that some were forced to maintain personal connections with white businessmen may have averted some of the violence that plagued most of the West. One example is Portland, where such figures as Seid Back and Moy Back Hin maintained consistently cordial relations with the neutral, rather than anti-Chinese, city government [Note 5]

With regard to Chicago, several instances are cited on the website of the Chinese American Museum of Chicago http://www.ccamuseum.org , of Moy and Chin family members who in the 1880s and 1890s became friendly with the Irish-American and Italian-American establishments and who were skilled enough at intercultural communication to gain the support of the local English-American media [Note 3]. In 19th century New York, the presence of well-connected Chinese figures like Honorary Deputy Sheriff Tom Lee and the pioneering civil rights advocate Wong Chin Foo gave the Chinese community there a very different public image from that of Chinese in Sacramento or San Francisco [Note 4].

Chinese leaders in the big California cities had different backgrounds than Chinese leaders elsewhere in North America. While in Chicago and New York, community leadership came from merchants and other businessmen, in California it was in the hands of diplomats and high-status scholars brought specially from China to head the various regional associations. Such leaders, legitimized by Chinese law and traditional attitudes, must often have worked effectively among their countrymen. They also could use their high-level connections in China to mobilize the imperial government on the behalf of Chinese in and outside California. On the other hand, knowing little English and with minimal experience in coping with North American conditions, imported leaders of this kind could rarely serve as bridge-builders to the non-Chinese world.

The reasons varied. In Idaho, the unusual even-handedness of the state courts, including the Idaho Supreme Court, played a major role [Note 1]. In British Columbia, violence was tempered by the fact that most courts and enforcement agencies were under central, rather than local, government control. In Chicago and New York, an important factor was the presence of numerous other immigrant ethnic groups, many of them as exotic and as seemingly non-assimilable as the Chinese [Note 2]. And in Portland and Seattle, and in Chicago and New York as well, another moderating influence was the presence of local Chinese leaders with the political and social skills needed to work closely with the European-American elite.

A tribute to Goon's perceived influence in forwarding the interests of local Chinese comes from a previously unrecognized source, the diplomatic archives of China as preserved at the Academia Sinica in Taiwan. In a report by Wu Chang, a young diplomat sent out to Seattle from the embassy in Washington, Goon received full credit for this: "As far as the issue of the [Chinese] being poorly treated, this city does not seem to see many such instances. This is because Honorary Consul Goon has been good at protecting [them].” A complete translation of the relevant part of Chang's report will be found elsewhere on this website. [Note 8]

Chang may have been exaggerating the personal abilities of one individual. And yet, judging by attitude of the white press in the above-cited cities -- New York, Chicago, Portland, and Seattle --, one finds that transcultural social skills on the part of local Chinese leaders did play a role in helping their communities resist hostility from elements in the white population.

Were such skills common? They cannot have been rare, although appointed community leaders may not always to have possessed them. After all, emigrants and sojourners in similar situations must have self-selected for such qualities as linguistic skill and cultural flexibility, just as diplomats were sometimes (but not always) chosen for similar qualities. One thinks of the remarkable case of Sam Moy in Chicago, who in the 1880s and 1890s became known for such popular but very un-Chinese activities as playing practical jokes on white residents of the tough Levee District. An even more remarkable case was that of Wu Ting Fang [Cantonese: Ng Choy], the great Chinese diplomat born in Taishan, Along with Wu's intelligent defense of Chinese interests, his acerbic wit gained him real popularity with the American press. Both Moy and Wu showed that a Chinese sense of humor, suitably translated, could be a real asset in dealing with members of the white elite in North America.

Did Goon Dip exhibit such skills? Surviving sources do not mention his sense of humor. However, he does seem to have been a likable individual by American standards. As attested by Chilberg, at least some white Seattlites enjoyed his company, and others--like the woman for whom he named his daughter, Ella McBride--became close friends [Note 9]. Did transcultural personal connections of this kind make a practical difference? We cannot prove they did. And yet how could they not make a difference, in a world where westerners were told repeatedly that all Chinese were hopelessly alien?

Chin Gee Hee, 1901.

陈宜禧

| ||||

Moy Back Hin, 1901

梅伯显

Wong Chin Foo, 1877.

王清福

| ||||

Wu Ting Fang, 1897

伍廷芳

Colonel F. A. Bee, a European-American who served as consul under the Chinese consul-general in San Francisco, was one of those assigned to investigate the massacre. His comments show that he was not only an effective spokesman and propagandist but also not immune to ethnic prejudices of his own. The article itself, being published in Oregon, also shows that Northwestern agitators would have been well aware of the Rock Springs precedent when they began planning for Tacoma, Seattle, and other anti-Chinese violence in the Pacific Northwest

[Daily Astorian (Astoria, Oregon), October 8, 1885, page 3]

"THE WYOMING MASSACRE. Americans Had Nothing to Do With It.

"Colonel F. A. Bee, resident consul for China at San Francisco, has returned to that place from an investigation of the Chinese massacre at Rock Springs, Wyoming. In an interview with the Alta [a San Francisco newspaper] Colonel Bee relates what he found:

" 'Were any of the white men engaged in this butchery Americans?' basked the reporter.

" 'Americans!' exclaimed Colonel Bee, as if struck by a thunderbolt. 'Americans! Don't disgrace your

country by asking such a question as that. Thank God, no! Most of them were laborers brought from Europe by the Union Pacific company to operate the mines. Cornwall and Wales furnished the major share. Brutes who have lived underground from boyhood were the assassins. Low-browed, square-jawed, ignorant and villainously visaged men, men whom you would fear to meet on a crowded street even if you were armed on both hips. Clubs and rocks aided the murderers, for when they found a wounded and helpless Chinaman, they dashed out his brains with the clubs or crushed in his skull with rocks. While the men were shooting the Chinese and firing cabins, the women were looting the vacated dwellings. There are, I should think about four hundred white men in the settlement. The women are bold and rude, and if a soldier strays away from camp the women stone him and howl at him until he is glad to beat a retreat.' "

Murder of Chinese at Deception Pass

In the 1880s, legend claims, the notorious Benjamin Ure drowned numerous Chinese on occasions when his smuggling boat was about to be captured by the U. S. Revenue Service. The scene of the crimes is said to have been Deception Pass, a strait between Whidbey and Fidalgo Islands about forty miles south of the Canadian border.

The horrifying legend and Wikipedia's joking reference to it are discussed elsewhere on this website. To see this, click here.

Deception Pass.

Ambassador Chang's official protest (see above) gave the names of eleven of the miners killed at Deep Creek. He spelled their names in English as Chea-po, Chea Suu, Chea Yow, Chea Shun, Chea Cheong, Chea Ling, Chea Chow, Chea Liu, Chung Kong, Mun Kow, and Kong Ngan. Their leader was Chea-po. Chang added that all eleven were from Panyu 番禺 county in Guangdong province and that San Francisco's Sam Yup ("Three Counties") Association 三邑会馆 , which covered Panyu as well as two other counties, had carried out an investigation at the orders of the Chinese Consul General in San Francisco. Although the Consul General was a subordinate of Chang and reported regularly to him, Chang's published diary does not confirm that he had been informed about the massacre much before January 28, 1888, when he discussed the matter with an American lawyer (Note 1). He sent his formal protest to Bayard shortly after that.

Now more details have been found in an official history of the Sam Yup Association, written in 1999 but based on an earlier history, the authors of which had access to even earlier records preserved at the Sam Yup headquarters in San Francisco (Note 2). Whether those records are still in existence is uncertain. Because of the Association's documents and the ambassador's diary, we now know that Deep Creek was called Muddy Water Creek [濁水坑] in Chinese in those days.

Entrance to Sam Yup headquarters inSan Francisco, 2011

The Role of Portland's Chinese Community 钵崙华埠也曾相助

The present-day Chinese Conso-lidated Benevolent Association building in Portland, 2011

Memorial for a Massacre 蛇河深渊屠杀纪念碑

As of November 2011, plans have been nearly finalized for placing a memorial, an inscribed piece of granite, at the massacre site, now officially called Chinese Massacre Cove. The committee behind the plans has decided on appropriate texts (in Chinese, English, and Nez Perce), obtained the support of the Oregon State Park system, begun raising the necessary funds, and gained the backing of numerous people in the Lewiston area.

The Committee hopes that the memorial can be ready by June of next year. A special website for the project has just gone on line

Committee members checking possible

sites for the memorial at Massacre Cove.

Photo by Garry Bush, 10/2011

New Data on the Victims 蛇河深渊遇害苦主

"This list, it seems to me, is a sufficient answer to the suggestion made to the committee that such events do not occur with sufficient frequency to require this legislative action."

"OUR DISHONORABLE RECORD 我们不光荣的纪录

.

"The second objection was that in more than a century only seven cases have occurred to which by any possibility this legislation could apply. In answer to this I can only set out an official list of the outrages committed in recent years.

"At Rock Springs, Wyoming, on November 30. 1885, there was an armed attack by one hundred men on a

Chinese settlement in a mining town in which all the houses were burnt and in which twenty eight Chinamen

lost their lives and sixteen were wounded, and all their property was destroyed

In a similar attack in Squak Valley, Washington. three lives were lost and four wounded

At Orofino in Idaho. five lives were lost

At Anaconda in Montana, four lives were lost

At Snake River, Oregon, ten lives were lost

In Juneau, Alaska, 100 Chinese were expelled by lawless violence from their homes and the territory

"Nine Italians were lynched in New Orleans in 1891.

In August, 1895, one Mexican was lynched in California.

In October, 1895. one Mexican was lynched in Texas.

In 1895, three Italians were lynched at Walsenberg, Colorado.

In 1896, three Italians were lynched at Hahnville, Louisiana.

In 1899, three Italians were lynched at Tallulah, Louisiana.

In 1901, three Italians were lynched at Erin, Mississippi.

In 1910, one Italian was lynched in Florida.

President Taft's 1914 incident list: Chinese were not the only aliens to be targets of ethnic violence. Italians and Mexicans were too.

排挤华, 麦, 意, 非,裔移民风潮 – 美总统有数

In 1914, ex-President and future Supreme Court Justice William Taft wrote two articles for Independent Magazine outlining the need for laws to correct a serious problem: that the federal government had no jurisdiction over racist murders, even when those killed were supposedly protected by international treaties. As current efforts by states and cities to enact their own laws against Mexicans show, the problem is still with us.

Taft was also deeply opposed to the unlawful killing of American citizens, including the lynching of blacks. However, he saw that in constitutional terms, as a matter for state rather than federal law. In contrast, he felt that the murder of non-citizens protected by treaties was clearly a federal offense and that new laws were needed (see W. H. Taft, The United States and Peace, 1914, p 49)

William H. Taft, “The Unprotected Alien and Our National Responsibility.” The Independent, Feb 9, 1914, pp 204-208

"In an official note of February 15, 1886, there was a statement of riots at Bloomfield, Redding Creek, Eureka, and other towns in California involving murder, arson, robbery, and expulsion; also a statement that a great many thousand Chinese had been driven from their homes.

William Howard Taft, 1911

Chinese Officials Warn Governor Squires 西雅图侨领呼救