| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

This page and the Reburial page focus on how and why early North American Chinese died and on the ways in which their countrymen handled those deaths, the rituals they followed, how the dead were buried, and why and how they were dug up again later and sent back to China.

A. Causes of Chinese Deaths 早期華裔死因

Three articles on causes of death among Chinese migrants will be found here:

(1) Violent deaths in British Columbia, 加拿大卑斯省早期鲜有自然死 Updated 01/04/2010

(2) Chinese suicide in Washington State. 華裔自殺比率 01/04/2010

(3) Causes of Chinese deaths in Washington State. 華州-死亡因素 01/09/2010 [revised 12/08/2015]

(4) Deaths and the fate of the deceased in Alaskan Canneries 06/04/2013

The articles introduce two major historical problems: the high incidence of tuberculosis and the high rate of suicide among early Chinese in North America.

B. Chinese Funerals in North America 北美洲的华人葬礼

Ceremonies for death and burial were great events for Chinese in the U.S. and Canada. Along with Lunar New Year, due to the processions, firecrackers, and sacrificial food involved, funerals were highly visible aspects of Overseas Chinese life. As such, they were frequently discribed in English-language books and newspapers.

(1) Funerals in San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle, ca. 1900 出殡, 上山, 入土12/29/2011, revised 03/20/2012

Because Chinatown funerals have so often been desribed, we will not devote much space to them here. Interested readers should look at the articles in Sue Fawn Ching and Priscilla Wegars eds., Chinese American Death Rituals: Respecting the Ancestors (AltaMira Press, 2005). The article by Linda Sun Crowder on San Francisco's Chinese mortuary tradition (pages 195-240) is especially useful.

C. North American Chinese Cemeteries 北美洲華人坟场

The bodies of the dead were buried in or near the communities where they lived at the time of death. Here are articles on four cemeteries,

(1) Lone Mountain in San Francisco. 12/29/2011

(2) an unidentified early cemetery in Portland. 俄勒岗州钵仑华人墓地 10/13/2009

(3) Spokane's Fairmount. 華州士卜顷坟场纪录 12/13/2010

In all these cases. many or all of the deceased were buried with the intention of digging them up after a few years and shipping their bones back to China. In other cases, as at Walla Walla and with the Goon family in Seattle, the deceased may have been intended to rest permanently in that spot.

(5) Mountain View in Walla Walla. 落叶不归根 : 華州抓李抓嚹早期华人墓地 09/21/2009

(6) Seattle's Goon Dip 衣锦不还乡:西雅图阮洽家族墓冢 decides that his body will not be returned to China 12/27/2011

Birthplace played a crucial role in determining one's final burial place:

(7) Language Divisions at Harling Point, Victoria. 从墓碑认识移民故里05/14/2010

Those wishing to pursue further the subject of Chinese cemeteries in North America should look at Terry Abraham's on-line cemetery list, http://www.uiweb.uidaho.edu/special-collections/papers/ch_cem.htm and his Chinese Cemeteries Study Discussion Listserve (see http://www.uiweb.uidaho.edu/special-collections/cemintro.htm)

Walla Walla: many Chinese dead were not exhumed and sent home to China 落叶不归根 : 华州抓李抓嚹早期华人墓地

It is a truism among historians that before World War II the bodies of deceased Chinese were almost always shipped back from America to China. Indeed, the cemeteries of many U.S. cities contain very few Chinese graves earlier than 1940. And yet there are exceptions -- enough to raise doubts about the usual explanation, that all Chinese felt they must be buried at home in order to receive offerings from their descendents.

One such exception may be found in Wall Walla's Mountain View Cemetery, where a good many early Chinese graves exist at the northeast corner of the cemetery's Palm and Poplar Streets. More than 70 Chinese and six Japanese tombstones survive, arranged in six North-South rows. The earliest grave belongs to a Japanese lady of Buddhist faith, bearing a Meiji date equivalent to 1909. There is only one Chinese woman in the plot. She died in 1947.

Interestingly, about 30 of the burials occurred before 1940. Considering that Walla Walla cannot have had more than several hundred Chinese residents in the 1920s and 1930s (note 1), such a large number of Chinese graves seems to show that, in Walla Walla, a fairly large percentage of deceased Chinese stayed where they were first buried. While many must have been exhumed and sent back to their home towns in Guangdong, many others were not. Why? Not because of poverty. Mountain View is a middle-class cemetery without a charitable potter's field area for the very poor. Did most of the deceased not have families in Guangdong to take care of their graves? That is possible. It is also possible that Walla Walla, as a small city distant from the major Chinese population centers, lacked the usual sojourners' institutions charged with ensuring that the dead, after a suitable time in an American grave, would be dug up again and sent to China.

Today a stone monument, probably erected after the 1980s and engraved in both English and Chinese, stands next to an older brick burner for offerings [Note 2]. The latter was mentioned in a September 1952 issue of the Walla Walla Union-Bulletin.

Note 1. Acording to the Union-Bulletin (02/09/1947), Walla Walla' s Chinese population had declined from 800, presumably in the late19th century,

to about100 in the 1940s.

Note 2. A comprehensive list of offering burners in Overseas Chinese cemeteries has been compiled by Terry Abraham, at

In Nevada, graves of Chinese who seem not to have intended that their bodies be returned to China are fairly common. See Sue Fawn Chung, Fred P. Frampton, and Timothy W. Murphy, "Venerate these bones ...", in Sue Fawn Chuing and Priscilla Wegars eds., Chinese American Death Rituals. AltaMira Press p 110

Chinese graves in Mountain View Cemetery, Walla Walla,

Washington State

The earliest Chinese grave in the cemetery, dated April 1919, is that of Mr. Wei En 魏恩. Wei was a Taishanese from Guangdong. In fact, every Chinese buried at Mountain View Cemetery came from the Four Counties (= Siyi or Siyap) area of Guangdong: from Taishan 台山, Xinhui 新會, Kaiping 開平, and Heshan 鹤山. Taishan was the most popular place of origin, with Xinhui in second place. Like most other early Chinese immigrants to North America, all would have spoken the Taishan (= Toisan) dialect of Cantonese.

Tombstone of Japan-

ese woman, 1909

Tombstone of Wei En, 1919

Portland 1908: A Long-Gone Memorial Stone

俄勒岗州.钵仑:华人传统墓地

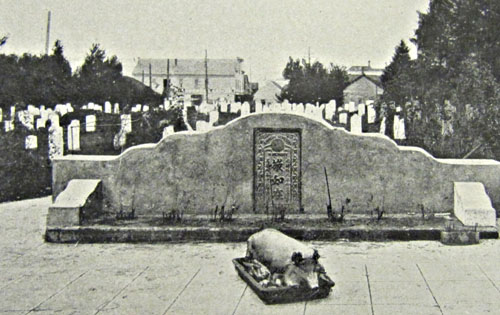

The black and white photograph was published in Pacific Monthly, July-Dec 1908, a popular monthly magazine from Portland. The caption reads, "Chinese Cemetery in Portland. Though callous as to the living, the Chinese are extremely regardful of the dead."

The three characters on the stone reads "敬如在" [we honor you as though you were present]. The English inscriptions above and below the big round dot reads, "Chinese cemetery" "In Memory". The text (and the sacrificial roast pig in the foreground) may be meant for all Chinese buried there rather than for one important man. The stone was carved in Guangxu the 28th year, or 1902, and was placed in this cemetery, which is probably the Lone Fir. The memorial does not exist any more.

Harling Point Chinese Cemetery, Victoria, B.C.

加拿大.域多利:哈宁角华人坟场

The historical data that follows is taken largely from the writings of the University of Victoria's David Chuenyan Lai, who not only played a leading role in preserving the cemetery but has studied it intensively (note 1), supplemented by personal communication with him. Data on individual tombs are from the editors' own observations

Encroachment by the sea had made Victoria's old Chinese cemetery at Ross Bay unusable by the end of the 19th century. So in 1903, deceased Chinese began to be buried at Harling Point, where the local Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) owned a vacant headland property of 3.5 acres. As elsewhere in Canada and the U.S., most Chinese burials at Harling Point were intended to be temporary. The dead usually were exhumed after a suitable number of years and “repatriated” to China for permanent burial. The last group repatriation was made in1937, after which the Japanese War made repatriation impossible. Hence, remains of BC Chinese began to accumulate in a storage vault at the cemetery until a permanent mass burial took place at Harling Point in 1961. The cemetery had already been closed to new individual burials since 1950, although a few tombstones bear early 1950s dates.

The layout is symmetrical around a central axis. At the base of the axis are the twin furnace towers, for burning paper offerings, and an altar; both made of concrete in 1903. The burials spread out on the East and West wings of the cemetery grounds. It is not clear if the cemetery was planned to be segregated by gender and place of origin. At present, judging by tombstones that are currently readable, most burials of women seem to be located in the northwest quarter. The southeast quarter seems to have been used by individuals from the Sze Yup (Mandarin Siyi, “Four Counties) area, while the northeast quarter contains a number of individuals from Panyu in the Sam Yup (Sanyi; “Three Counties”) area as well as Sze Yup individuals and others. [Note: the next article on this web page contains more data on ethnic subdivisions at the cemetery]

The oldest tombstone for a man is dated October 3, 1928, and belongs to Cheng Hing Yueng (鄭慶仰, pinyin: Zheng Qingyang). Cheng was the president of the Victoria's Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Associaation between 1917 and 1920. In 1918, an issue of the Tai Hon Kong Bo 大汉公报newspaper reported that Cheng was also a member of the Chee Kung Tong secret society as well as the Dart Coon Club 达权 in Victoria, with a consistent interest in building libraries for both organizations.

Two days after Cheng Hing Yueng's death, Mar Sue (马秀,

马心恭, Ma Sum Kung; pinyin: Ma Xingong) followed in his footsteps. Mr. Mar was one of the founders of the Victoria's CCBA. He gave away a golden plaque at a friend’s 72th birthday party, according to Da Hon Kong Bo. Mr. Mar’s wife came from the Guo family and was buried near but not next to him in 1933.

Cheng Hing Yueng’s clansman, Cheng Kuei Kwang (鄭鉅光, Mandarin:Zheng Juguang), was so proud of his membership in the Chee Kung Tang, the Chinese Freemasons,.that in 1948 he carried that identity to the other world. On his concrete slab was engraved a Masonic emblem, the only one of the kind in the cemetery. In 1917, according to the Tai Hon Kong Bo, he had been elected a board member of the Chemainus branch of the Chee Kung Tang, a position he kept for several decades.

When the 60-year old Mr. Lam Kong Lup 林杠立 (pinyin: Lin Gongli), died in 1929, he was given a splendid funeral. A parade with more than 30 cars and several hundred mourners was led by city police. His obituary stated that he was revered as an old timer doing honest business in Victoria. He ran a pharmacy, Kwong Shon Tai 廣信泰, with an in-house herbalist, from the 1910s onward. The shop apparently doubled up as a dried foods grocery too.

Not every grave was for a person of Chinese descent. The CCBA accepted Caucasian wives of Chinese as part of the community. A simple granite tombstone, marked “Louise Schmidt, wife of C. Die” (趙大, pinyin: Zhao Da), stands in the general female quarter.

References:

David Chuenyan Lai, "The Chinese Cemetery in Victoria," B.C. Studies, No. 75, Autumn 1987.

David T.H. Lee, A History of Chinese In Canada, 1967, pp. 176. 李东海, 加拿大华侨史1967.

For more pictures see http://www.oldcem.bc.ca/cem_ch.htm and http://www.flickr.com/photos/ngawangchodron/sets/72157622534453666/

Cemetery Gateway

Burners for offerings, with the Olympic Mountains and the Strait of Juan de Fuca in the background

Of the 250+ tombstones in readable condition, most date to the 1930s and 1940s. The oldest tombstone in the cemetery belongs to a Ms. Wong (pinyin: Huang) who married into the Ma family. She died in 1925 and was given a marble tablet. The second oldest resident in the cemetery was also a lady, a Ms Li, who married into the Wang family and died in 1927, remembered by a concrete slab. Her husband, Wong Bun Sing 王品成 (pinyin: Wang Pin-cheng), died five years later and was buried in a somewhat more splendid grave.

Tombstone of Mrs. Ma, 1925,

台山白沙南安里

Tombstone of Mrs. Wang, 1927

Tombstone of Lam Kong Lup, 1929

Tombstone of Louise Schmidt, 1930s

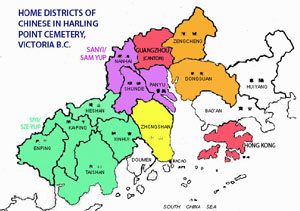

One often hears that early Chinese immigrants were all Taishanese, meaning that they spoke the Taishan 台山(Toisan) dialect of a group of four (now five) counties west of Guangzhou or Canton, the provincial capital. That is indeed where the majority of residents at Harling Cemetery, Victoria came from, as indicated by the inscriptions on the tombstones. People from those counties, colored green here, call themselves Szeyap or Siyap 四邑 [four-county] people, a way of evoking regional connectedness.

However, many non-Szeyap Chinese lived in Victoria too--in fact the early Chinese community there seems to have been more metropolitan than any other Chinatown in Northwest America. As shown by the Harling Cemetery tombstones, the second largest speech group were Cantonese, whose language was not mutually comprehensible with Taishanese. Standard Cantonese is spoken in Hong Kong and Guangzhou (Canton) and in the three counties colored magenta on the map. Immigrants from those counties called themselves Samyap 三邑 [three-county] people. Among them, Panyu 番禺 folks were the most adventurous. The Harling cemetery shows a good many people from Panyu but none from Nanhai or Shunde.

Cantonese rather than Taishanese was probably the lingua franca used among Chinese in Victoria between 1880 and 1910. There are several reasons for thinking so. First, the English names of people and shops in Victoria often reflect a Cantonese reading. Second, as the tombstones show, Victoria had other Chinese language groups as well: from Zengcheng 增城, Dongguan 东莞 and Zhongshan 中山, colored orange and yellow on the map. Although the people of those districts use certain terms and accents different from standard Cantonese, their dialects, unlike Taishanese, are understandable by Cantonese speakers. Third, the leading Chinese businesses in Victoria during those three decades, all of which dealt in imported Asian commodities, had to maintain connections with bankers and suppliers in China, Hong Kong, Macao, and Singapore. Taishanese, which is not widely understood outside the Four County area, would not have been a convenient business language.

It is unusual in the Pacific Northwest to hear about immigrants from Zengcheng, a place more famous for lychee fruit than for emigrants. However, Zengcheng people were among the early immigrants to California (Him Mark Lai 2004: p 41), so their presence in Victoria is not a real surprise. The same is true of immigrants from Dongguan county, whose gravestones are present at Harling Point but in numbers too small to be included in the following tables. Although rare in the Northwest, it made sense for a few to be in Victoria in the late 19th century, when the opium trade was at its height. As noted elsewhere on this website (click here) , Dongguan was the home county of the opium firms that became Macao’s Sing Wo Co., which established a branch, Sing Wo Chan, in Victoria in 1886.

Tombstone of Cheng Hing Yueng, 1928 恩平君堂村

Tombstone of Mar Sue, 1928

台山海宴横山村

Tombstone of Cheng Kuei Kwang, 1928

恩平 石潭村

The 1961 mass burials at Harling Point (from a storage vault at the cemetery–see the preceding article) were organized by county of origin. 841 Chinese were thus interred and a record made of names, dates, and birthplaces. The tombstones on individual graves also contain birthplace data. In 1986, 213 such tombstones were still readable. David Lai (1987: Tables 2 & 3), has tabulated information on counties of origin from both sources:

District

Mass

Mass Individual

Individual

It will be seen that no Hakkas (Mandarin: Keren) appear in the table, although as the Tam Kung temple shows, they were prominent in Chinese Victoria. This is because the Hakkas of southern Guangdong did not have a county of their own and hence would have been listed as natives of Panyu, Zengcheng, Zhongshan, etc. There is also no one listed as coming from Hong Kong or Guangzhou, due to the custom of claiming an ancestral home in a county-level town or village even though one's father, grandfather, and great-grandfather might have lived their entire lives in downtown Guangzhou or Hong Kong.

For more on the proportions of different Chinese ethnic groups in the BC population, see the article "Home Counties in Guangdong and Sub-Ethnicity of Immigrants" under "Regions" on this website.

References: David Chuenyan Lai, "The Chinese Cemetery in Victoria," B.C. Studies, No. 75, Autumn 1987; Him Mark Lai, Becoming Chinese American, a history of communities and institutions, Altamira Press, 2004.

Language Divisions in the Graveyard 从墓碑认识移民故里

Violent Chinese Deaths in British Columbia, 1879-1891

加拿大卑斯省早期鲜有自然安乐死

The suicide rate among Chinese in British Columbia was also high, as shown by data in the British Columbia Provincial Archives. The archives contain results of coroners' inquests for much of the province, from the late 1870s onward. These data are not comparable to the Washington State data because they do not include deaths due to disease, the inquests having been conducted only on deaths that were violent or otherwise potentially criminal. Deaths from disease, presumably certified by a doctor, were not the concern of Canadian coroners.

Hence, 12.2% of total Chinese deaths were due to suicide. This figure may be modified somewhat when we get data on the few Washington counties with Chinese populations (i.e., Jefferson, Kitsap, and Pierce) that are missing from the Archives database, but the general trend is clear. Many Chinese in the Pacific Northwest killed themselves: enough that suicide was the second leading cause of death, exceeded only by tuberculosis.

The question is, how unusual was this? Does it show that North American Chinese led lives so hard and desperate that suicide was often the only way out? Some historians would favor such an explanation. And yet one could also argue that a 12.2% rate of suicides to total deaths was and is not unusual for populations like that of Chinese sojourners--relatively young, healthy, and with a strong tendency to be born and become old elsewhere, so that the population did not experience the high mortality rates typical of early childhood and old age.

One modern population with similar characteristics is that of active-duty military personnel: healthy, predominantly male, and mostly between 20 and 50 years old, A recent study shows that between 1980 and 2005, the percentage of self-inflicted deaths to all deaths in the U.S. armed forces ranged from a low of 9.32% (in 2005) to a high of 24.04% (in 1995) [Note 2]. Seen in this light, a Chinese suicide rate of 12.2% seems tragic but not extraordinary.

The editors agree that the stresses in modern military life are quite different from those experienced by a sojourning Chinese laborer in 19th century North America, and we do not wish to minimize the hardships suffered by either group. The subject of American Chinese suicide involves a whole complex of historical social, cultural, and psychological issues that need further study. While suicide may turn out to have been a dominating problem for early Chinese immigrants, we do not want to press the panic button yet. Life for Chinese on this continent was indeed difficult. But was it difficult enough to cause an epidemic of mental instability, in a group of otherwise well-balanced individuals with a seemingly exceptional capacity for coping with danger, hardship, and loneliness?

Note 1: Data on causes of death have been compiled from the on-line Washington State Archives, http://www.digitalarchives.wa.gov/Search.aspx

Note 2: Anne Leland and Mari-Jana Oboroceanu, American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics, Congressional Research Service 7.5700 www.crs.gov RL32492, 2009

Note 3: The photo of Don Toy comes from the Chinese Exclusion Files at NARA (the National Archives and Records Administration). As far as we know, in spite of his evidently depressed state, he did not commit suicide.

In the course of compiling statistics from early death certificates on file in the Washington State Archives, the editors have come on an interesting fact. Between 1891 and 1907, in most counties with significant Chinese populations, the suicide rate for Chinese was very high.

A total of 114 deaths was recorded during 16 years [Note 1]. This is about what one would expect in a healthy population of several thousand persons, many of them moving in and out of the state, averaging 30-50 years old. What is unexpected, however, is that 14 of the total deaths seem to have been self-inflicted: 2 by hanging, 8 by opium poisoning, and 4 simply as "suicide." While it is conceivable that the two hanging cases represent murder, the eight cases of opium poisoning must represent deliberate ingestion--in those days, Chinese in North America smoked opium rather than swallowing or injecting it, and getting an accidental overdose via opium pipe, which needed several minutes of preparation per pipeful and at least 30-40 total pipefuls to induce death, was almost impossible.

Chinese Suicides in Washington State, 1891-1907 華州早期自殺比率高

Don Toy, Laundryman, Tacoma, 1911: A life of quiet desperation?

The on-line index posted by the Archives contains only names, dates, and briefly stated causes of death. Much more could be gotten from the actual records, to be found on Reel 2372 of the provincial Attorney General's files, GR 1327. We have not been able to consult those yet. However, even the index alone tells us much more than is otherwise known about Chinese mortality in most other parts of North America during the 19th century.

The suicide rate is high (and would have been higher if coroners had examined deaths from opium--see above) while the murder rate is surprisingly low. Thousands of Chinese lived in or passed through British Columbia during this period. It is possible that local police and coroners listed some homicides as accidents out of sympathy for the murderers.

Chinese were not alone in suffering from accidents while at work. Whites and Indians (the coroners' records seem to use that term rather than specific ethnic names) also died while felling trees, catching fish, and so forth.

Only one Chinese woman is listed: Ling Gum in 1888. She was "asphyxiated from a charcoal fire in her stove."

Chinese cemetery in Victoria, B.C. See below.

Death: Dying, Funerals, and Cemeteries in North America 塵土歸路: 墓地 葬仪 过程

DISEASE 疾病

Appendicitis - - - - - - - -. -

Asthma

Beriberi

Bowel inflammation

Congenital debility [6 month-old girl] - - - -

Diarrhea

Heart disease 心脏病 - - - - - - -

Hemorrhea

Hepatitis, Interstitial

Hernia, strangulated - - - - - - -

Hydrothorax

Indigestion

Influenza ("La Grippe")

Jaundice (and jaundice with hemorrhea)

Kidney cysts - - - - - - - - -

Kidney (Bright's disease, nephritis) 肾病

Liver cancer

Locomotor ataxia [from syphilis?]

Lung, hemorrhea

Myelitis - - - - - - - - - -

Pancreatitis

Paralysis

Pneumonia

Rheumatism

Sarcoma - - - - - - - - - -

Scurvy

Septicemia

Stomach, strangulated

Stroke, aneurysm (apoplexy, cerebral hemorrhage)

Tuberculosis (consumption, phthisis) 肺病 - -

Typhoid

Unknown

Uremia

Uterine cancer - - - - - -- - - -

ACCIDENT 意外事故

Killed by train

Killed by falling timber

Drowned

Crushed by elevator

Concussion of brain

Fractured skull

Asphyxiated by pois. gas

"Accidentally"

Poisoning, "probably"

Strangulation

Suffocation from coal gas

MURDER & EXECUTION 谋殺/问吊

Legal hanging

"Murdered"

Knife wound

External violence

SUICIDE 自殺

Hanging 上吊

Opium 鸦片

"Suicide" 自杀

Note that the several entries assigned by us to the "Accident" category may actually have been murders (i,e., strangulation, poisoning, concussion of brain, and fractured skull) or suicides (strangulation). Back in the 19th century, keepers of death records on the county level may indeed have decided to cover up a murder or two, but as of now this cannot be proved or disproved.

The same sources that yield data on Chinese suicides (see above) also list other causes of Chinese deaths during the same period. The Washington State Archives do not contain death records for two countries with substantial Chinese populations, Pierce and Jefferson. However, the other high-Chinese counties are all represented. The statistics summarized here cover at least three-quarters of recorded Chinese deaths in Washington in the sixteen years under study.

True, a good many Chinese deaths were never recorded. We know this by comparing newspaper accounts with official death records, although we have no idea why (carelessness, laziness, or deliberate negligence?) or what proportion of deaths may be missing. But the incompleteness of the records is not a serious problem for our present purpose, which is simply to begin to understand why Chinese residents of Washington died. .As noted in the preceding essay, the Chinese population was predominantly male, healthy, and between 20 and 50. Hence, childhood diseases were rare among North American Chinese, as were illnesses of old age like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and many forms of cancer. The low incidence of liver disease among local Chinese may be related to abstemious drinking habits and a low rate of alcoholism.

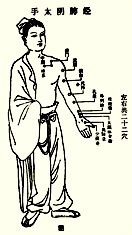

By far the leading cause of death was tuberculosis. We are not certain whether Chinese suffered more from TB than members of other ethnic groups, although we have heard it said that the Pacific Northwest had a higher incidence of the disease than most other parts of the country. The crowded living conditions of Chinese laborers may have made them vulnerable to tuberculosis. Did widespread opium use, which often involved the sharing of opium pipes, also make them vulnerable? Perhaps. Few contemporary physicians seem to have thought so, but it is a possibility.

Source: online Washington State Archives, http://www.digitalarchives.wa.gov/Search.aspx. Data in the above table come from each county listed in the website's "Death Records," obtained by checking surnames likely to belong to people of Chinese descent. Data from Jefferson and Pierce counties, which are not included in the state archive website, will be added later.

1

1

1

1

1

1

8

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

1

6

2

1

1

1

1

1

2

1

1

1

2

1

1

28

1

1

1

1

1

1

4

1

1

2

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

1

1

2

8

4

Causes of Chinese Deaths in Washington State, 1891-1907

華州早期華裔死亡因素

Accupuncure points for lungs and lung disease, including tuberculosis. From Chen Xiuyuan's famed Lingsuji Zhujieyao (ca.1800), probably used by early North American Chinese

陈修园. 灵素集注节要

版权 Copyright is free for non-profit use: : click here for more information

The Ledgers of Fairmount Cemetery, Spokane, Washington 華州.士卜顷:坟场纪录

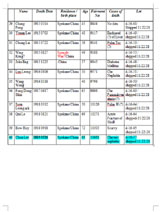

This cause of death data from Fairmount should be compared with another entry on this page. "Causes of death in Washington State", taken from government records.

The city of Spokane, in eastern Washington, is fortunate in having two old cemeteries, Fairmont and Greenwood, that have preserved burial records extending back to the 19th century. Both cemeteries contain Chinese graves. Both, contrary to local beliefs, began accepting Chinese burials at about the same time, in the 1890s. Entries for Chinese in the ledgers of Fairmount have been extracted and appear here. It will be seen that Fairmount, unusually for a cemetery, often recorded the cause of death as well as the name of the deceased, date, and grave location. Most of the burials were shipped back to Hong Kong in 1928.

Old Chinese section, Fairmount Cemetery. None of these graves is as old as those in the ledgers

Page from Fairmount Cemetery's burial ledgers.

Chinese burial data from Fairmount Cemetery record ledgers.

金山西北角 - 华裔研究中心

Interment at Lone Mountain: A View of the Graveside Ceremony

At Lone Mountain Cemetery in San Francisco, "The Chinese have a vault in which they deposit those corpses which are to be sent to China." (Daily Alta California, 6 January 1858)

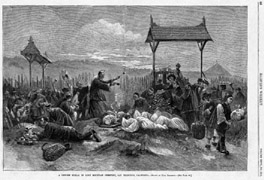

Finding a place for interment was not easy because of local regulations and prejudices. North American cemeteries tended to be segregated, by religion if not by race, and were often controlled by religious or fraternal groups that refused burial space to the "heathen Chinee." Even if Chinese succeeded gaining entry to a given cemetery, they were usually relegated to a particular part of the cemetery that had been bought or leased by a Chinese organization. Nowadays, the organization in question is often the Chong Wa (the CCBA or Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association). In the 19th century, Chinese burial areas elsewhere than San Francisco tended to be controlled by the Chee Kung Tong or other secret society,

Burial ritual at Lone Mountain, San Francisco, 1882. This famous picture exists in two versions, both of which seem to have appeared in copies of Harpers' Magazine in 1882. The one on the left depicts a burial at dusk or dawn; the one on the right shows the same burial in the light of day. Both are masterful examples of propagandistic art. Needless to say, the one on the left, which non-Chinese readers must have found even more disturbing than the other, has been more often reprinted. The editors do not know whether Daoist priests ever dominated real burial ceremonies in this way, or whether white-clad mourners were accustomed to crawl over the soil on their stomachs. Neither priests nor mourners usually behaved this way in China.

The Chinese also buried their dead in actual graves at Lone Mountain as well as other cemeteries. In San Francisco and nearby communities during the 19th century, responsibility for funerals was taken by the appropriate shantang, the charity arm of the huiguan or regional association of the deceased. In other parts of North America, many and perhaps most funerals were conducted by the secret society, often the Chee Kung Tong, to which the deceased belonged. As far as the editors know, the great majority of such funerals ended in actual interment rather than depositing the body in a special vault. In a few cases involving individuals from rich families, the coffin seems to have been carried to the cemetery, given the usual ritual treatment, and than carried back to Chinatown again and sent to China on the next available ship. In many other cases, the body was dug up again after a number of years and returned to China then. The process of exhumation, shipment, and reburial is described on the Reburial page of this website.

C. Chinese Cemeteries in North America 北美洲華人坟场

Causes of Chinese Deaths

(Reburial Articles)

D. Exhumation and Shipment to China 先友回唐

Until the late 1930s, most Chinese who died and were buried in the Pacific Northwest and West (as well as many of those who died elsewhere in North America) were dug up again after a number of years and sent back to China.

(0) Why?

(1) Reburial customs among the Southern Chinese 华南流行二次葬 12/22/2011

(2) MarkTwain on the return of Chinese bodies to China 美国马克吐温的观察 12/26/2011

(3) Victoria: Registration for exhuming and returning bodies 域多利是加拿大执运先友的总站

12/27/2011

05/10/2012

(4) Women in the Burial Registers 女先友的执运纪录 12/27/2011

(5) Digging up the dead: Who did it? How? 執骨工人是誰? 01/03/2012, revised 03/08/2012

(6) Whose bones were they? An answer from Alaska 05/24/2012

(7) Rules for digging up the dead 怎样管理执骨, 洗骨 03/10/2012

(8) The perils of exhumation: a ghost story 2/25/2013

(9) Packing the bones -- Why metal boxes? 怎样装载骨殖? 03/10/2012

理执骨, 洗骨, 运骨之前 01/03/2012

洗骨, 运骨之后 01/03/2012

(12) Seattle: other Chinatowns too helped with repatriating the dead 西雅图也参与执运工程

01/04/2012

(13) Storing exhumed bodies before shipment 绝无仅有的照片 - 王容伦拍的域多利贮骨所

revised 01/13/2012

(14) Shipping the dead to China

E. After the Bodies Reached China 从香港到故里

Virtually all Chinese remains that arrived back in China were processed through the Tung Wah Hospital, Hong Kong's leading charitable institution. Ideally, remains of each individual would then be passed on to family members for placing in suitable containers, usually jars, and interring in family cemeteries where offerings to the dead would be made regularly, expecially on the Qing-Ming Festival in th spring and the Hungry Ghost Festival in the fall. Inevitably, however, some remains would not be claimed. Those would accumulate at the level either of Tung Wah in Hong Kong or of charitable organizarions in the relevant home district. Those organizations would bury such remains in charity cemeteries, sometimes in mass graves with a single monument and sometimes in separate graves with individual grave markers.

(2) The Interior of the Tung Wah Coffin Home 东华义庄 03/18/2012

(3) Unclaimed bodies: charity cemeteries in China 义冢安葬 無主孤魂 12/28/2011

(4) Claimed bodies: burial in the family cemetery 01/07/2012

(5) A lone voice spoke out: bone repatriation was a bad idea 04/23/2012

Victoria, B.C.

San Francisco

Walla Walla, WA

B. Funerals 出殡, 上山, 入土

Suey Sing Tong leader's funeral, from San Francisco Call, 1900-12-07

Lee Won Sai's funeral, from Portland Oregonian, 1903-02-06

As was also true of American fraternal organizations, some secret like the Masons and others not-so-secret like the Oddfellows, Chinese secret societies took a strong interest in funerals. They were the ones who conducted the most elaborate funerary rituals and, in the 19th century at least, often bought or leased cemetery space for burying members.

Shown here are two images of contemporary funerals. On the right is that of a wealthy and respectable merchant from Portland, who died in 1903. Although the Oregonian does not say so, it is likely that the event was organized by the Chee Kung Tong, of which he must have been a member. On the left is the funeral of Lem Yuk Lip, called a top-ranked highbinder by the Call: "the leader of the notorious Suey Sing Tong, the most famous and wicked of Chinese societies in this city." Lem Yuk Lip died, presumably of natural causes, in 1900.

Seattle: Goon Dip decides that America, not China, will be his final burial place

衣锦不还乡: 西雅图阮洽家族墓冢

This picture helps to explain why Goon Dip 阮洽, the Chinese honorary consul in Seatle between 1909 and 1933, one of the richest and mst influential Chinese in the Pacific Northwest, seems to have decided that his body would not be sent back to his home village, Shangge in Doushan Meinam, Taishan, Guangdong 台山县,斗山镇,美南乡,上阁村 The ground-level horizontal stones surrounding the monument indicate that Goon had a large family in thie Seattle-Portland area. He could count on them to see that his grave was properly maintained and to make any sacrifices considered appropriate for a Christian like himself. Another reason why Goon may have wanted his body to stay in Seattle: he may not have been close to his relatives in Shangge. As the editors found when they visited in 2011, he did send some money back to the village but did not take nearly as much interest in it as the villagers themselves may have expected from a man who became their most successful emigrant.

Goon family plot in Lake View Cemetery, Seattle

His money was for two major projects at Shangge Village, as remembered by senior members of the clan. One was to help build and maintain the ancestral hall of Goon Dip's lineage, which is now among a complex of four such halls at the end of the village. Known as Goon Ren Dip 阮仁洽 by his clan, his name was engraved on the donors' tablet inside the hall. The other project was the construction of a concrete path at the front row of the village. The legend was that Goon Dip solely financed its construction.

This page was last updated: August 30, 2018

Dick Kay and Steve Goon, descendants of Goon Dip, have okayed the publication by CINARC of images of the family's grave.

The editors thank the many helpful Goon clan members in Shangge for their inspiration.

Two later memorials bearing the same Chinese inscription, unusual in American cemeteries, exist today at Portland's Lincoln Memoral Park Cemetery. The one on the left is fairly new. It stands on the edge of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association burial ground and is a gift from the cemetery. The one below, which bears the same "honor you as if you were present" text and a similar design as the 1908 memorial, is located at the bottom of the hill on the Magnolia plot.

An interesting feature of early funerals for certain wealthy individuals: the coffin was conveyed with due pomp, including numerous carriages, a fancy hearse, and at least one brass band, to the cemetery. The coffin was buried in the normal manner, with the usual ceremonies and sacrifices. However, then it was promptly dug up again. This was slated to happen to the coffin of Seattle's Tom Gin How, a leader of the Chee Kung and Hip Sing Tongs, after his funeral in 1906:

"The coffin will be placed in the ground and the sod will be placed over it, but the following day it will be disinterred and removed to the morgue to be prepared for shipment on the next steamer for China. This is the invariable custom. The parents of Tom Gin are still alive and well in Canton, as is his grandson. The permanent burial will take place there." -- Seattle Times 1906-10-22, p 4

(UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED ALL DATA ON THIS PAGE COMES FROM THE EDITORS' OWN RESEARCH ON PRIMARY SOURCES & ARTIFACTS)

As in other Alaskan cannery areas, many Chinese worked seasonally in canneries in Ketchikan, a town with very few year-round Chinese residents. Historical data pertaining to Chinese are generally scarce in Ketchikan, but, fortunately for historians, the town's leading funeral home kept good records of any deceased Chinese who had received its services. Because deaths had to be registered and the dead properly disposed of, and because Ketchikan was the administrative center of the area, one assumes that a large percentage of local Chinese deaths appear in the funeral home's records. Those consulted here cover the years 1911-1921. They include names, dates, ages, places and causes of death, cemetery location (where appropriate), mortuary services provided, cost, and—not unimportantly—who paid those costs.

A total of twenty deceased Chinese passed through the funeral home between 1911 and 1921. The occupations of two were not specified. One was a cook. One was a restaurant owner. The other sixteen were cannery workers. All of the former and three of the latter were buried in Ketchikan, perhaps permanently. The other eleven cannery workers were embalmed, placed in coffins, and shipped back to either Seattle or Portland, depending in part at least on where their winter homes or labor contractors were located.

Average age at death

52.8

52.8

48.0

48.0

Disposition:

Buried in Ketchikan

3

3

4

4

Sent to Portland or Seattle

11

11

0

0

Not recorded

2

2

The cause of death is given for ten of the cannery group: three died from heart failure, and one each from tuberculosis, accident, burns, blood poison, hemorrhage of stomach, rupture of a blood vessel, interfusion of bowels (?), general debility, and old age. Two of the non-cannery group died of gunshot wounds, the result of a gambling dispute. It is interesting that many of the cannery workers died of diseases associated with old age, in contrast with the recorded causes of death (with a much higher high proportion of tuberculosis and a lower proportion of heart disease) for the larger sample of early Washington State Chinese presented above. The Chinese in Alaska canneries were older than one might expect in a job that normally required long hours and sustained physical effort.

Deaths and the Fate of the Deceased in Southern Alaskan Canneries

Those who were not sent to Washington or Oregon were probably buried here, in Ketchikan's old Bayview Cemetery. They may have been dug up again later for shipment back to China: there currently are no identifiable Chinese graves left in Bayview.

As for the cannery workers who were returned to Seattle or Portland, we do not know what happened to them. They were all in costly caskets and had been expensively embalmed, presumably because this was required by local Alaskan laws. The embalming must have posed a problem. Decay of the bodies would have been greatly slowed, so they could not be buried in a Washington or Oregon cemetery and then exhumed again after the customary seven or ten years, when the flesh had decayed from the bones (click here). On the other hand, the caskets must have been bulky and heavy, which would have increased the price of shipping the body onward to San Francisco and then to China while still in its Ketchikan casket. The bodies of rich individuals were sometimes sent directly to China in western caskets, as in the case of the Victoria merchant Lee Yau Kan in 1888 (click here). But the Ketchikan cannery men were far from rich. While their employers and Seattle's or Portland's CCBA might conceivably have paid the cost of shipping the embalmed body in the casket onward to the relevant shantang in San Francisco, they could not have afforded more than that.

So, what did the shantang do with the bodies and caskets afterward? As discussed elsewhere on this website, sending deceased sojourners home to their native villages was a central function (and a near-sacred duty) of San Francisco's regional associations, the huiguan, and their service subsidiaries, the shantang. There was no option: the embalmed bodies absolutely had to go back across the Pacific. But how? We would like to know.

For more on Ketchikan's cannery workers, click here.

The editors wish to thank Richard H. VanCleave, Senior Curator of the Ketchikan Museums, for showing us the funeral records and sending us a scan of one we missed.

Ketchikan, Alaska, 1900-1930. Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Bayview Cemetery, Ketchikan, ca. 2010. Photo by Judy Z on findagrave.com

1