| ||||

Opium in Chinese America 鸦片烟在美洲

We, the editors, realize that the subject of Chinese opium use in 19th century North America can cause unease and controversy. However, we think it is important, especially in the Pacific Northwest. Many writers still treat opium smoking by Chinese as a moral and even ethnic issue, as if Chinese were somehow more guilty than other people of addiction to opiate drugs. Chinese-American historians have tended to shy away from the subject entirely. Do they feel that it somehow reflects badly on their culture or themselves? Must one keep quiet about one's predecessors' vices, in spite of the horrifying damage that was sometimes caused, in order to validate one's cultural inheritance?

We don't think so. Opium use among Chinese immigrants was very widespread, economically important, and -- until 1908-9 -- perfectly legal in most parts of the United States and Canada. The smugglers of opium, most of whom were European-Americans, were criminals, though tolerated and even respected in the Pacific Northwest. Smokers of opium, the majority of whom in those days were Chinese, may have been addicts but were neither criminals nor outcasts. Opium made hard lives more bearable and, perhaps due to easy availability and modest prices, seems not to have caused nearly as much violent crime as alcohol did then or as opioid drugs like heroin and oxycontin do nowadays.

So we propose to discuss opium use among North American Chinese frankly and straightforwardly. We feel that there is no shame in what happened a hundred years ago and that there are lessons in it for the modern world. While many American and Canadian Chinese of the late 1800s may have been addicts, their cultural systems kept the drug under control in spite of that. We in the early 2000s should learn to do the same.

Smuggling Incidents and Stories 走私個案

Some of these entries also appear in the "Annals of Northwestern Smuggling" section of the Topics web page, http://www.cinarc.org/Topics.html#anchor_269

1885 Captain H. F. Beecher, the newly appointed (and unusually bribe-resistant) Collector of the U.S. Customs office at Port Townsend, pulls off a coup. Learning that steamers on the Washington-Alaska route often loaded illicit opium at Victoria on the way north and then brought it back south labeled as a staple commodity, he posts a pair of trusted men as spies in Victoria. In November they send word to Beecher that the steamship Idaho has loaded fourteen suspicious barrels marked "Ships Stores" at Victoria and proceeded north. When the Idaho reappears, it is searched rigorously. Only 933 pounds of opium are found, hidden in a washstand. What has happened to the rest? Luckily, Beecher's informants learn that most of it has been offloaded at Kassan Bay Fish Saltery at the south end of Alaska. Pressing the Revenue Cutter Wolcott into service, Beecher races to Kassan Bay. There he discovers the fourteen barrels, labeled "Salted Fish" but filled with smoking opium of the best quality. A total of 3,033 half-pounds of the drug are seized, which net the government about $40,000 when resold. Up to then, it is "the largest seizure [in market value] of any commodity ever made in the history of the Customs Service" [J. G. McCurdy, Pacific Monthly 1910 pp 1886-7]

[The Customs Service office responsible for a seizure was allowed to auction the opium off to local merchants and to keep the proceeds. This provided the same kind of incentive (and potential for abuse) as modern rules allowing police departments to keep vehicles used for transporting illegal narcotics. In Beecher's case, he may have been exaggerating the amount he got from reselling the 3033 half-pounds of opium. As indicated above, $13 per half-pound (i.e., per can of 5 Chinese ounces) was an implausibly high price. $6-$9 per can would have been more realistic.]

1888 Edwin A Gardner, former Chief Customs Inspector at Puget Sound, is arrested on February 15 in northern New York State for trying to being 1500 pounds of unstamped opium into the US from Canada, in a sleigh, The opium is stored in the U.S. Customs office in Ogdensburg, NY. Gardner apparently gets out of this by claiming that it was part of his official duties but is then arrested again, for arranging the smuggling of another 500 pounds of opium from Canada to Tacoma on the steamer George Starr. At his trial on June 29, he is accused of trying to cover his tracks by sending the opium to Wallula in Eastern Washington by train, then to Portland, then to Seattle. He is further accused of entering into a conspiracy with other customs inspectors. Collector H. F. Beecher, Gardner's superior, is not named as a member of the conspiracy but agrees to be a witness for the defense. On O October 6, Gardner's lawyer, J. Charles Haines of Chicago, is arrested in Seattle for having removed the original 1500 pounds from Ogdensburg; he presumably has brought it to Washington State and passed it to Gardner. No Chinese are mentioned in the relevant newspaper articles. [NY Times 02-15-1888 p 8, 05-22-1888 p 9, 06-29-1888 p 2, 10-06-1888 p 2]

1899 "Customs Officer Ruger discovered nearly 200 pounds of opium in a pawnbroker's shop on Second Street [in Seattle] but could not obtain a clue to the smugglers until yesterday... It turns out that extensive smuggling operations have been going on here for some time, and $100,000 worth is brought in yearly by sloops from Victoria, British Columbia, which send boats to the shore near Seattle to leave the drug with professionals on shore. It is then either sold to Chinese of shipped to Portland and San Francisco for transportation East in trunks, valises, etc. [New York Times 01-06-1889, p 1]

1890 “First documented opium seizure -- made by USRC Wolcott on 31 August 1890 … Stationed in the Straits of Juan de Fuca, the cutter conducted a boarding of the American steamer George E. Starr. It found an undeclared quantity of opium and seized it and the vessel.”

[http://coastguardnews.com/a-legacy-of-maritime-law-enforcement/2007/12/04/] [But see the Beecher story above, in 1885]

[Note that the crime involved is that of evading customs duties. The sale and use of opium did not become illegal in the U.S. until 1909. It was banned in British Columbia a year earlier, in 1908. Repackaging of imported opium in Victoria's Fisgard Street Chinatown, mostly for reshipment to the U.S., reached a peak in the early 1890s] [http://web.uvic.ca/vv/student/chinatown/opium/p3.html]

1892 Some British Columbian smugglers may be bypassing Washington State, as suggested by this newspaper article: "The smuggling schooner Halcyon has returned to the Victoria (B.C.) Harbor as secretly and mysteriously as when she sailed from that place six weeks ago, heavily laden with opium and Chinese. Her officers and crew will give no information regarding the cruise, but the United States Secret Service detectives who are in Victoria watching her movements learned through one of he seamen that the vessel had touched on the California Coast and at the Hawaiian Islands since leaving Victoria." [New York Times 1892-10-02]

1893 A nice case from a secondary source: "In December 1893, the U. S. district attorney for Oregon indicted twenty-eight men in the United States District Court. The case turned on events that had occurred two months earlier, in October of the same year, when a 450-pound shipment of opium was loaded aboard the steamer Wilmington in Victoria, British Columbia. Suspicious of the shipment, a Victoria customs agent telegraphed ahead to the Astoria, Oregon customs house, located at the mouth of the Columbia River—the main waterway into the city of Portland. Working on a tip, the owners of the Wilmington headed downriver to retrieve the ship and dump its illicit contents. But customs agents had already apprehended the shipment. Then began one of the largest nineteenth-century opium and immigrant smuggling cases on the West Coast. Of the Portland-British Columbia operation, one San Francisco newspaper declared, 'the [smuggling] has been carried to an extent and audacity little short of marvelous." [Griffith, Sarah M., "Border Crossings: Race, Class, and Smuggling in Pacific Coast Chinese Immigrant Society," Western Historical Quarterly 2008, vol 5, 4: pp 473-492

1895 It is announced that two new revenue cutters are being built in Port Townsend for use by the Coast Guard in Puget Sound. Each will be heavily armed, have a crew of one lieutenant and seven men, and – thanks to a vertical inverted direct-acting compound engine with a high-pressure cylinder of 7 inches and a 42-inch diameter propeller – "will reach a top speed of 15 knots." The main purpose of the ships will be to run down and capture “small steamers engaged in these waters in smuggling into the United States opium and Chinamen.” The opium is said to come from “manufactories” in Victoria, B.C. [New York Times 1895-12-08, p 19]

[Note: the “manufacturing” involved refining and repackaging opium from elsewhere, mostly from British India via Hong Kong. As stated above, throughout the 19th century the use of opium was quite legal, though somewhat stigmatized, in both Canada and the U.S. When the drug finally became illegal in the latter country in 1909, the criminal penalties involved were aimed almost entirely at opium for smoking, considered to be a vice of the Chinese. Opium for drinking in the form of alcohol solutions, abused mainly by Caucasians rather than Chinese, was not criminalized in the U.S. until much later. Laudanum, every bit as addicting as opium, stayed legal as a prescription drug. Paregoric (a camphorated opium extract) continued to be classified as an over-the-counter drug until 1973. Until then it could legally be sold without a prescription to anyone who asked for it.]

1902 An unusual case of a Chinese doing the actual smuggling: "Eighty pounds of opium, which a Chinese steward on the coast survey steamer Gedney will be charged with attempting to smuggle from Victoria to Seattle, was seized aboard the cutter by customs inspectors today. Eight parcels worth in the aggregate $1024 were found in the steward's department." Chicago Tribune 1902-10-02 p 16

1904 "Chief Wilkie of the secret service today gave out the following statement: "Secret Service agents have been investigating the suspected smuggling of opium between Seattle and Portland. On Sunday last $20,000 worth of crude opium was seized and S. B. Stevens, alias Tuttle, W. S. Cree, and Alfred Larson, all of Seattle, were arrested. Stevens is charged with being the principal. His methods, it is stated, were unique. Chinese merchants at Victoria imported the opium, and it was landed during the night at a point near Seattle. Stevens had two skeleton pianos, it is said, and two large iron safes into which the opium was packed. The receptacles were then shipped by freight to four fictitious names in Portland, where the distributors got possession of the opium." Chicago Tribune 1904-05-24 p 18

[Stevens' methods, though unique, seem not to have been excessively subtle. Even the dullest customs agent, one would think, would eventually have become suspicious about two large iron safes, not to mention a pair of unplayable "skeleton" pianos, being shipped back and forth repeatedly between Seattle and Portland]

For still more smuggling incidents and stories, please click here

1893 A small seizure of opium, 63 half-pound tins, valued at $6 per tin"; from J. G. McCurdy, Pacific Monthly 1910 p 190]

Imagined opium "den" from an 1874 publication. Like many such visual and verbal images, it is partly racist in intention, depicting Chinese as being astoundingly (and unbelievably) depraved. Credit: Wikicommons

Tray with opium smoking equipment: 2 pipes, a lamp, tools for handling the opium, a pipe bowl rack, and various opium containers. Credit: Steven Martin

Opium Use

Equipment 鴉片煙具

Pieces of opium cans and sherds of opium pipe bowls are found during just about every excavation of early Chinese sites in the U.S. and Canada. The finest selection of such items is in Priscilla Wegars' Asian American Comparative Collection of Moscow, Idaho (http://www.uiweb.uidaho.edu/LS/AACC/). Dr. Wegars has given us permission to include photographs of some of those items on this webpage.

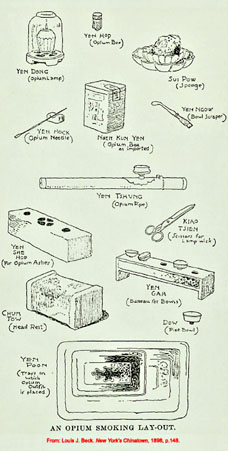

In the meantime, this drawing, from Louis J. Beck's 1898 New York's Chinatown, as reproduced on a website of the University of Victoria, may help readers in identifying the various kinds of opium equipment. Note that some of: Beck's terms are not understandable to modern Cantonese speakers

English Beck's Mandarin Characters

Cantonese

opium lamp yen dong yan deng 煙燈

opium box yen hop yan he 煙盒

sponge sui pow shui pao 水泡

水泡

opium needle yen hock yan zhen? 煙針?

opium tin noen kun yen lai lu yan? 来路煙?

noen kun yen lai lu yan? 来路煙?

(as imported)

pipe bowl yen ngow yan gua? 煙刮?

scraper

opium pipe yen tshung yan qiang 煙槍

ash container yen she hop yan hui he? 煙灰盒?

lamp wick kiao tsien jiao jian 鉸剪

scissors

head rest chum tow chen tou 枕頭

pipe bowl rack yen gar yan ge 煙格

煙格

pipe bowl dow dou 煙斗

opium set tray yen poon yan pan 煙盤

Incidentally, readers should be cautious about buying old opium pipes from antique shops or on the Internet. The great majority of such pipes were destroyed long ago by opium sellers and addicts seeking the "yen pox," the tarry residue, inside. Such residues, though unpleasant-tasting, still contained enough opiate alkaloids to satisfy users' craving for the drug. Hence, almost all "opium pipes" currently on the market are either recent reproductions or for tobacco rather than opium.

An Addicted Prostitute Testifies 鴉片煙友

1890s opium den with white patrons, from Harpers Magazine. The lack of erotic behavior or other intense interaction is realistic. As Emily Wharton says in her testimony: "the desire to get your pipe ready is far too earnest a business to allow of any desire for idle talk,"

a. Victoria: the largest opium making center outside Asia 域埠- 欧美鴉片烟总汇 [updated 08/22/12]

a1. Canada's other opium makers: Vancouver, New Westminster, Nanaimo [posted 01/09/11]

b. Refining and packaging opium for sale [posted 8/9/09]

c. Opium brand names 鴉片烟牌子 [updated 11/16/09]

d. More opium brand names: from gold mining sites in the Cariboo [updated 01/18/10]

d1 Even more opium brand names, from Idaho's AACC [posted 3/3/11]

d2 Opium cans from Australia [posted 2/6/12]

d3 More opium brands from Australia: the Hong Kong-North American connection [posted 2/23/12]

d4 Even more, this time from Victoria in the South, not Queensland in the North [posted 3/6/2015]

d5 The best-dated opium brands: from railroad camps in Montana [posted 3/6/12]

f. Opium cans or "tins" 鴉片烟罐 [posted 8/14/09]

g. Opium cans of the prohibited period 1909年禁烟以后的洋烟罐 [updated 1/17/11]

g1 Kwangchow-Wan brands and the French connection [posted 1/17/11, updated 3/26/13]

g2 Opium smuggling and Lam Kee's opium factory in Macao [posted 3/26/13]

h. Fake opium brands in San Francisco 三藩市冒牌鴉片烟 [posted 9/6/09]

h1 Counterfeiting Hong Kong opium [posted 9/15/12]

h2 Paper Labels on Opium Cans [posted 4/18/11]

i.. Commercial trickery in Canadian opium labeling [posted 12/28/10]

j.. Opium Retailers in San Francisco, 1900-1904 三藩市鴉片烟华商 [posted 12/17/09]

k.. Triumph of 19th century chemistry: making Middle Eastern opium smokable 土耳其鴉片 [12/29/09]

l.. Direct evidence of a Middle East/Balkans to Pacific Northwest connection [posted 12/29/09]

m. A public-spirited narcotics cartel? The modest profits of Victoria's opium refiners [posted 08/21/12]

b. A governor-general and his wife visit a Victoria opium "factory" in 1895 [posted 11/10/09]

c. Smuggling incidents and tales 個案 [updated 8/14/09]

d. More smuggling incidents and tales The Great Smuggling Ring, 1893 [posted 12/15/09]

d1. "A prepossessing young widow" from Port Angeles [posted 01/24/12]

e. "The pretty smuggler and her pathetic story" [posted 11/1/09]

f.. A fashionable young lady gets caught with a half-ton of opium [updated 12/17/09]

g. Diving for opium in Puget Sound: a true story 打捞 [updated 10/1/09]

a. Opium equipment in the U.S., 1896 煙具 [posted 8/1/09]

b. How opium pipes worked [posted 10/8/09]

c. Opium pipe bowls show Chinese immigrants' middle-class aspirations [posted 10/8/09]

e. Brand dominance in the opium pipe bowl trade [posted 10/27/09]

e1 Pipe bowl brands found in both America and Australia [posted 2/23/12]

f. North American opium lamps [posted 11/3/09]

g. Commerce in opium lamp chimneys 烟灯灯罩广告[posted 12/1/09]

i. How much opium did white Americans use? The Iowa case [posted 12/19/09]

i-1. Marketing opium to white-Americans before 1914 [posted 7/15/2012]

j. The opium addicts of Albany, NY [posted 12/21/09]

k. Opium suicides [posted 12/17/10]

b. Addiction Cures for North American Chinese [posted 10/15/09]

c. Curing addicts and outlawing the opium trade: the missionary connection [posted 10/19/09]

d. British Columbia defends Britain against Opium War slander [posted12/28/09]

e. The Addict's Progress: anti-opium propaganda in China, 1883 [posted 04/21/11]

a. Lurid pictures of opium dens [posted 05/30/10, updated 04/18/11]

b. Exaggerating harm from opium use [posted 05/30/10]

Refining and Packaging Opium for Sale 提煉与包装

The growing of poppies and the production of raw opium does not concern us here. It is enough to say that the old Anglo-Indian monopoly had been broken by the late 19th century but that opium from Patna and Malwa in eastern and western India, produced under the tight control of the colonial British government, was still greatly preferred by the world's opium smokers. The Indian products, especially the Patna kind, fetched a considerably higher price than opium from other poppy-growing areas such as Egypt, Persia, Turkey, and China itself.

Even more prestigious were Indian opiums refined in Hong Kong, where the water and master refiners were thought to be the best in the world. This refining process does concern us, because the end result, opium "boiled" or "cooked" and packaged by a small number of Hong Kong firms, had a central influence on the economies and lifestyles of many North American Chinese in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Opium refining was not confined to eastern Asia. Among the places where it was done on a large scale (but reputedly with less concern for quality) were Victoria, Vancouver, and New Westminster in British Columbia, ideally located for wholesaling (or smuggling) their products to the United States. The province's close connections with Britain must have given it an advantage in getting raw opium from the world's most famous opium-growing areas, Patna and Malwa in British India. Whether all British Columbia opium really came from there is not so clear. The low price for which it sold might suggest otherwise.

One of the first North American researchers to recognize the importance of brand consciousness in the North American opium trade was Priscilla Wegars of the Asian American Comparative Collection at the University of Idaho, at which the above can seals were photographed. By assembling a large collection of excavated opium cans, each marked with impressed brand name seals, from archaeological sites in the western United States, she has been able to show that smokers continued to be loyal to Fook Lung and Lai Yuen, in spite of their higher price, for many decades, that cans of these high-prestige brands were often reused, and that a major lower-priced competitor was Victoria in Canada, where a number of companies refined opium and sold most it for smuggling into the United States.

The general subject of opium cans is discussed below.

Cantonese

Mandarin

Mandarin

Characters

Characters

.1. Sheung Wan Lai Yuen Shangwan Liyuan 上環麗源

.2. Sheung Wan Fook Lung Shangwan Fulong 上環福隆

上環福隆

.3. Hong Kong Hop Lung Xianggang Helong 香港合隆

香港合隆

.4. Hong Kong Wa Hing Xianggang Huaxing 香港華興

香港華興

.5. Wik To Lei Tai Soong Yudouli Taixun  域多厘泰巽

域多厘泰巽

Note: Sheung Wan is a well known part of Hong Kong Island. .

1. Lai Yuen 2. Fook Lung 3. Hop Lung 4. Wa Hing 5. Tai Soong (Victoria)

Refining and Testing Opium in China, 1881. Illustrated London News 1881-04-16

Opium Brand Names 名牌鸦片烟

The names and stamped seals of Hong Kong opium producers were among the first internationally recognized brand names in the history of Asia. From the 1870s onward they were recognized in North America as well.

Elizabeth Sinn (J Chinese Overseas 1, 1:p 16-42, 2005) has studied the Hong Kong opium trade in strictly economic (rather than moral or medical) terms. She points our that the most favored brands of opium, Fook Lung and Lai Yuen, along with the less popular Ping Kee brand, were produced by the Yen Wo 仁和 syndicate of merchants from Dongguan, a Cantonese-speaking district southeast of Canton. Yen Wo's great rival was the Wo Hang 和興 syndicate of merchants from Xinhui, southwest of Canton, where Taishanese, the dialect of most North American Chinese immigrants, was spoken. These language and regional ties should have given Wo Hang a major advantage in selling opium to smokers in the U.S. and Canada. However, Wo Hang's brands, which included Hop Lung and Wa Hing, were consistently less popular on the other side of the Pacific.

Opium cans or "tins" 鸦片烟罐

The size of opium cans was standardized. Each held exactly 5 Chinese ounces (= liang or taels) of refined opium, about 6 1/2 ounces avoirdupois but usually calculated as a half-pound by American newspapers and the Customs Service. In the United States in 1891, the wholesale price ranged from $6.80 (for Victoria opium) to $9.00 (for the best Hong Kong opium). At retail to users, the opium from a single can of Hong Kong opium sold at a markup of $2.25 (Note 1). The retailers, although regarded at the time as extraordinarily greedy, seem to have been satisfied with a smaller per-unit profit than any modern seller of alcohol in shops and bars.

Remains of such cans, generally well preserved, are common at archaeological sites where Chinese North Americans formerly lived, both in rural mining districts and in urban Chinatowns.

Christopher Merritt of the University of Montana has recently (Note 2) made a discovery that helps to explain why excavated opium cans tend to be in good condition: dented and twisted perhaps, but not rusted or decayed. Merritt analyzed 17 cans of this kind from four sites in Montana. None of the cans were of iron protected by a layer of tin -- hence, they were not the kind of container that was called a "tin" in Britain (and in those days, Canada) or a "tin can" in America. Instead, all of Merritt's cans were made of brass, an alloy of copper and zinc. The seams of the cans had been soldered with a lead-arsenic alloy such as was commonly used as soldering material in both China and the West.

Merritt suggests that the lead (and arsenic) might have had negative effects on the health of opium smokers. He is right in theory, and the copper could have had negative effects as well. However, cans of all kinds (for instance, salmon cans and corned beef) were regularly sealed with lead solder in those days, and those eating the contents of such cans were exposed to much greater quantities of poisonous metals than were opium smokers. On the positive side, the copper, zinc, and lead had antimicrobial and antifungal properties that must have helped to protect the opium inside the cans.

Their resistance to corrosion meant that opium cans could be, and often were, reused. Priscilla Wegars in conversation has suggested that this could mean retail fraud by sellers who repackaged cheap Victoria opium to pass it off as the more costly Hong Kong product. We do not doubt that in many cases she is correct. However, the re-use and resealing of old cans must also have had more innocent motives. As shown by the example on the far left of the above photograph, resealing sometimes left so many obvious signs of repair that such cans would not have fooled even the most naive of opium addicts.

Note 1: Stewart Culin, "Opium Smoking by the Chinese in Philadelphia," Am. Journ. Pharm. Oct 1891

Note 2: Christopher W. Merritt, "Elemental Analysis of Opium Cans from Archaeological Sites in Montana," Asian American Comparative Collection Newsletter, Supplement, March 2009

Opium can with brand seal from the AACC, Moscow, Idaho

Opium can with impressed brand seal from the AACC, Moscow, Idaho

Opium can from private

collection, Vancouver

Entrance to opium shop (in San Francisco?) Harpers Weekly 1881-09-24

Making & Selling Opium

Fake Opium Brands in San

Francisco

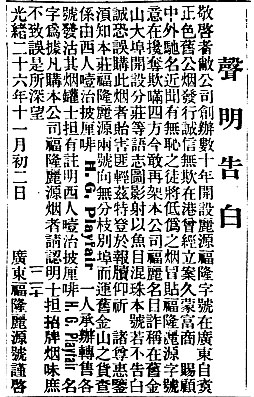

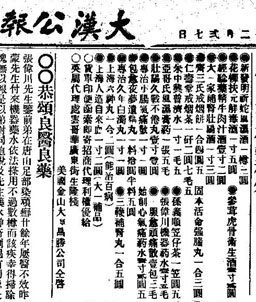

“Our companies have been operating for several decades with the brands “Lai Yuen” and “Fook Lung” in Guangdong, making and selling real and fair opium with sincerity and honesty. We have also registered in Hong Kong. We have been patronized by customers locally and abroad and are famous among them. Lately we have heard that some shameless people are using Lai Yuen and Fook Lung marks on counterfeit opium, trying to take away our business and cheat the people of the four quarters. Now they dare to use our companies' names, falsely claiming that they belong to a San Francisco branch; their intention is to pass as pearls even though they are just fish eyes. If we do not alert the public, customers might buy their products by mistake and suffer no slight losses. We are here to notify the public by having this announcement in the newspaper. We hope you the honorable readers will know that our Fook Lung and Lai Yuen companies do not have other branches in other cities. The products that are shipped to San Francisco are handled solely by our agent, a Westerner, H. G. Playfair. You should find that his name appears on the tax stamp adhering to the opium can. Those who buy Fook Lung and Lai Yuen opium must identify the right stamp, trade mark, and the fragrance of the opium to avoid making mistakes. This is our profound wish.

"Guangxu 26th year, the 2nd day of the 11th month. Humbly presented by Fook Lung and Lai Yuen Companies, Guangdong." (Translated by Chuimei Ho from notice in Chungsai Yatpo, San Francisco, 1900, Dec 31)

Notice in Chungsai Yatpo, 1900, Dec 31.

三藩市一九零零年中西日报

Diving for Opium in Puget Sound 打捞海底鴉片煙

The following story appeared in The Coast magazine in 1907. It purports to be from the memoirs of a retired opium smuggler who formerly had carried the drug by boat from British Columbia to Washington State before making his great discovery. The editors do not doubt that every word of his tale is true.

“I studied the tides in all that island country and knew the exact depth of water in every channel. I knew what kind of bottom could be counted on at every practicable landing and whether the shore was shelving or sheer. I learned the location of the most secluded coves and where a smuggler could run in and lay low up a creek when a revenue cutter threw up her smoke too close. That is a part of the education of the successful smuggler in those waters. I learned all the data well and profited by it. But one day I narrowly escaped being captured. They gave me a hard run and against my better judgment I dropped overboard in deeper water than I judged to be altogether safe. But I found bottom and my breathing tube was long enough to rise above the water

“That was the happy chance that put me in the way of making a fortune. I found myself walking on a sea bottom paved with cans of opium. At that particular point among the islands the revenue cutters have been accustomed to waylay the smuggler on their return from British Columbia, and there in their frantic haste to remove incriminating evidence, the hard pressed fugitives have been tossing overboard year after year whole boatloads of the expensive cans of poison. This practice kept up for forty years had resulted in a tremendous deposit of canned opium. The sea floor was literally paved with the precious little cans. You see the point was so well watched that the smugglers dared not return to recover their wealth. So they charged the loss up to bad luck and forgot the existence of the submarine deposit.

“I had found the mine. The next question was the means of converting it into cash.

“No point among the islands was so closely watched by the revenue fleet. It was a sort of crossroads of the marine tracks and at certain stages of the tide the only practicable route for south-bound boats. It was obvious that the utmost care must be taken in raising the treasure if my father's son was to profit by the enterprise. Having never been captured I was not personally known to the revenue officers, hence was able to put into effect a harmless little stratagem which worked perfectly. I secured a large scow decked over and on this I built a handsome cabin making a quite luxurious house boat. I then enlisted the assistance of a trusty friend. We laid in a prodigal supply of expensive fishing tackle, bird guns, and camping paraphernalia, then rigging ourselves out in modish attire, we had our house boat towed to the scene of the opium cache and anchored close in shore. Soon a revenue agent on watch in that locality came aboard and, after sampling our prime whisky and choice cigars, departed in the best of humor. Nothing wrong about us. Oh, no. We were just a pair of debonair and jolly young fellows--rich young swells--house-boating for pleasure

“Daylight we spent fishing, shooting on the adjacent island, or sleeping in the darkened cabin, for sleep we must and at night we could hardly spare the time. Every night I spent hours under water and my partner steadily hauled up baskets full of opium cans which he stowed safely away beneath the deck of the scow. Three months of nightly labor exhausted the field, but by this time the scow was well laden. Towed into a lonely cove near the city of Seattle, the cargo was easily transferred to those obscure channels of trade where vice pays the bills and always seems to be well supplied with money. Who would suspect a couple of wealthy young house-boating tourists of being implicated in the smuggling of opium? Certainly such a suspicion never crossed the minds of the sapient revenue officials.

“The next season we prospected for new opium fields and found a plentiful supply in several localities. At one point we came upon a sloop which had been scuttled in about six fathoms of water. There was a heavy cargo of opium aboard, and what gave us an unpleasant shock, two drowned Chinese. Ugly stories are circulated among the islands as to the propensity of the smugglers to leave the helpless Chinese to drown when the revenue cutters press them close, but this was the only evidence we ever discovered of such tragedies.

“For five seasons we loitered around among the islands living the careless opulent life of the young scions of the best families house-boating for pleasure. Many a revenue agent sampled our good cigars and laughed at our jokes, and each succeeding summer they joyously welcomed us and our hospitable house boat to those remote and loggy wilds.

“It was just like finding money but we worked out all the big deposits by the end of the fifth summer. As we had by this time a million dollars apiece in the Elliott Bay National bank, we sold the luxurious houseboat and returned to the paths of financial rectitude.”

Pierre Wakefield, “The Invisible Smuggler,” The Coast, July 1907, p 28-9

“I smuggled many years before I made the find that won for me independence. While there was considerable profit in the business, I should never have made a competence but for a fortunate chance. Thus my experience disproves the theory that industry and economy are certain to lead to success. I worked hard for years and never made over $1,500 a month. But when the goddess Chance smiled upon me my fortune was made.

“My method of procedure was simple and I often marvel at the lack of penetration on the part of the revenue men. I had a rubber breathing apparatus fitting over my head. A tube led up to the surface of the water and bobbing around among a lot of seaweed or rushes on a shallow bay it was hard to discover which was the rubber breathing tube and which the innocuous seaweed especially when you did not suspect the nature of the stratagem. When a revenue cutter's smoke loomed up dangerously close to me, I'd drop the cans overboard, then with leaden weights on my feet I d plunge in also and calmly wait while the emissaries of the law confiscated my empty skiff and steamed away. It was dead easy and reasonably profitable. Man is a curious animal: do you know there was just one privation connected with those enforced submarine trips that made me cross and unhappy? I couldn't smoke while waiting for the revenue officers to go away. You see, I was like those new coast defense cannon. I was built on the disappearing plan.

Shocked, Shocked! A Future Prime Minister Discovers British Columbia's Opium Refining and Export Trade

In 1908, W. L. Mackenzie King, Deputy Minister of Labour and a future prime minister of Canada, traveled to Vancouver to study the opium business. He went partly in response to the fact that two of those making claims for reparations after Vancouver's anti-Asian riots of the previous year were opium "manufacturers" (i.e., refiners). The Canadian government, which for several decades had collected major revenues from imports of raw opium and, indirectly, even more taxes from allowing refined opium to be smuggled into the U.S., professed shock at this revelation. Indignation mounted during and after Mackenzie King's investigation. The Canadian Parliament outlawed the opium trade that very same year. Several paragraphs of Mackenzie King's report are especially relevant:

"In the coast cities of Vancouver, Victoria and New Westminster, there are at least seven factories carrying on an extensive business in opium manufacture. It is estimated that the annual gross receipts of these combined concerns amounted, for the year 1907, to between $600,000 and $650,000. The crude opium is imported from India in coco-nut shells, it is 'manufactured' by a process of boiling into what is termed 'powdered' opium and subsequently into opium prepared for smoking. The [official Canadian Customs] returns show that large amounts of crude opium have been imported annually, and that the value of the crude opium imported in the nine months of the fiscal year 1906-7 was greater than the value of the amount imported in the twelve months of the preceding year; the figures for these periods being $262,818, and $261,943, respectively.

"The factories are owned and the entire work of manufacture is carried on by Chinese, between 70 and 100 persons being employed. One or two of the factories have been in existence for over twenty years, but the majority have been recently established. It is asserted by the owners of these establishments that all the opium manufactured is consumed in Canada by Chinese and white people, but there are strong reasons for believing that much of what is produced at the present time is smuggled into China and the coast cities of the United States. However, the amount consumed in Canada, if known, would probably appall the ordinary citizen who is inclined to believe that the habit is confined to the Chinese and by them indulged in only to a limited extent.

"The Chinese with whom I conversed on the subject, assured me that almost as much opium was sold to white people as to Chinese, and that the habit of opium smoking was making headway, not only among white men and boys, but also among women and girls. I saw evidences of the truth of these statements in my round of visits through some of the opium dens of Vancouver.

Like other Canadian government personnel before him, Mackenzie King was evidently concerned that Americans might react negatively to an official admission that the great bulk of the opium imported by and taxed in Canada was destined for re-export to the U.S. This must be why he suggests, implausibly, that quantities of the drug were being smuggled from Canada back to China.

His emphasis on opium smoking by white women and girls added a racy (and racist) fillip to the "social evil" argument. In reality, opium for smoking was insignificant as a threat to Canadian and American womanhood compared to opium as an ingredient in popular patent medicines, and no one was talking about outlawing those. It seems likely that Chinese Canadians rather than opiate narcotics were the real targets of Mackenzie King's investigation.

http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Report_on_the_Need_for_the_Suppression_of_the_Opium_Traffic_in_Canada

1909 Caucasian female opium smoker, from the Illustrated London News, Mar 13, 1909.

Smuggling Opium 美洲西北角走私個案

More Opium Brand Names: from gold mining sites in the Cariboo, etc.

在加拿大卑斯省发现的名牌鸦片烟

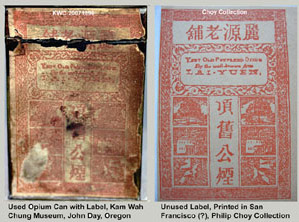

These impressed brand name seals appear here courtesy of a wonderful Canadian website, the North American Pioneer Chinese Virtual Museum, http://www.chinesecol.com/index.html. The website belongs to Reg and Roy, both of whom have important collections of Chinese artifacts. Most of their opium cans come from a late 19th century gold mining site in British Columbia, on the Fraser River not far from Williams Lake.

They write that the site yielded large numbers of Lai Yuen and Fook Long opium cans, plus a number of others with impressed seals that are unfamiliar to us. The absence of characters for place names at the top of these seals may indicate that most are local Canadian brands. As noted above, Sing Wo Chan and Kwong On Tai defnitely were Victoria companies. Other examples may be seen at http://www.chinesecol.com/opiumbrands/brands.html :

Reg and Roy are in contact with the finder of an even more extraordinary piece: an opium can with most of its paper label still intact. Many of the cans sold in North America apparently once had such labels, but almost none have survived. Judging from this example, the labels were printed in Canada or the U.S. and affixed by big retailers or wholesalers, not by the refiners whose impressed seals are on the lids of the cans.

On this label, the shop name at the top is too broken up to be readable. The rest of the printed text is in reasonable condition, however. It reads: "Honorable patrons: we guarantee that this is the real product or we replace it. Genuine aged opium. [illegible] Shop, Victoria [B.C.]."

We are surprised that anything like this could survive for long at an abandoned mining site. Yet the interior of British Columbia is not nearly as wet as the coastal areas. This relative dryness plus cold temperatures for part of the year may explain the good preservation of some organic materials from historic Chinese sites in the Chilcotin/Cariboo region.

Kwong On Tai

Sing Wo Chan

[?] On Lung

Reg points out that a can (or "tin") found in Australia also had a paper label, quite similar to the one shown here:

[At $6 per can, we may calculate that the author and his friend would have had to recover at least 400,000 cans to earn a million dollars each. Assuming that they worked steadily for 100 nights per summer for five years, and that a typical summer night in those days lasted 10 hours, the pair had to find an average of 80 cans per hour, or perhaps 100 cans per hour allowing for a few short breaks during each working night. This means that the author could not have afforded to waste time hunting around in the darkness for cans that were not in dense concertrations on the sea floor, and that therefore he had to leave many thousnds of cans behind -- perhaps even more than he managed to find and sell. We hope that this information has come to the attention of the Drug Enforcement Admninistration and that our federal anti-narcotics agents and their Canadian colleagues, by acting quickly and decisively, will succeed in forestalling the criminal elements that even now must be planning to start diving for the vast quantities of opium -- nowadays, worth much more than $6 per tin -- that still must litter the bottom of the Salish Sea.]

Opium Pipe Bowls Show Chinese Immigrants' Middle-Class Values

As one would expect, North American Chinese, who were not poor by the standards of Chinese in China, could afford good opium and good pipes to smoke it with. The issue of opium quality is discussed elsewhere on this page. Judging from archaeological finds of cans, the quality seems indeed to have been high enough. As for pipe bowls, the editors have not yet seen enough excavated examples to reach similar conclusions. However, it is clear that at least some bowls were of fine quality, and that the 19th century system that supplied North American Chinese with goods from China included quantities of opium paraphernalia that would have been far beyond the reach of poverty-stricken “coolies.”

Bowls for opium pipes have been found at most excavations of North American sites where Chinese lived during the 19th and early 20th centuries: for instance, at Market Street (San Jose), Weaverville, Riverside, Yema-Po (San Leandro), Wolf Creek (San Luis Obispo), Boyle Heights (Los Angeles) in California; at Deadwood in South Dakota; at Boise’s “Old China Town,” Idaho City, Centerville, and Sand Point in Idaho; at Shoshone Wells in Nevada; at El Paso in Texas; at Granite Creek (Prescott) in Arizona; and at various sites in British Columbia, including the Wing Sang store in Vancouver. (References to these excavations may be found by searching Google or Bing for the site or city name plus “opium.”)

Judging from published photographs,, the great majority of pipe bowls found in North America are made from dark buff, red-brown, or gray stoneware clays similar to those used for the famous “purple sand” ware of Yixing in Jiangsu province. Such clays, with good insulating properties and excellent thermal shock resistance, were traditionally seen by the Chinese as being especially well suited for making teapots and, in the 19th century, for making bowls for opium pipes as well. In China, even the most costly pipes usually had Yixing-type 宜兴 stoneware bowls, and less wealthy smokers, like middle-class tea drinkers, insisted on wares made of similar, if cheaper, clays..

As there seems to be some confusion on the Internet about how opium pipes were actually used, let us look at a description by the noted writer, observer, and New Yorker correspondent, Emily Hahn. Following this incident, which took place soon after she first reached Shanghai in the 1930s, Hahn deliberately became an addict, the lover of an aristocratic poet, and an expert on the opium habit among China's upper classes.

It will be seen that Hahn's friend Heh-van held the ceramic pipe bowl 烟斗(the "pottery cup") in his hand while inserting the heated opium wad, not fixing the bowl.into the polished bamboo pipe stem until just before reheating and inhaling the opium. Such bowls therefore had to be easily removable. Serious smokers usually had many more bowls than pipes, and the best bowls -- almost all of Yixing-type ceramic (see below) -- became collectors' items, cherished as much as fine teawares in China or the best meerschaum and briar tobacco pipes in Europe.

Certain books and websites insist on calling the bowls "dampers," even though that term was not used traditionally and has a quite different meaning (in connection with flues and fireplaces) in the English-speaking world. Our guess is that damper represents a misunderstanding by some non-English speaker, who believed that the bowl somehow made the opium vapor more humid. As that part of a pipe could not have such an effect, "bowl" seems to us a better term.

Note 1: Emily Hahn, "The Big Smoke," Times and Places, New York: Thomas Y. Cromwell Company, 1937; the article also appeared in the New Yorker magazine.

Note 2. All images are of the same pipe and bowl, Field Museum #126147.

Bowl inserted in pipe

Bowl removed from pipe

Top with "rimmed" hole in center

Bottom with maker's stamps

How Opium Pipes Worked 煙槍用法

Opium pipe with a Yixing-type clay bowl in the Field Museum's collection. Shanghai, ca. 1900. #126147

Excavated pipe bowls in the Asian American Comparative Collection, Moscow, Idaho

Excavated pipe bowls in the North American Pioneer Chinese Virtual Museum, British Columbia

Connoisseurs' Pipe Bowls 藏家追求的烟斗

Thus far, the editors have only looked at a handful of opium pipe bowls from Chinese North American sites that have readable inscriptions, in the form of seals stamped into the clay before firing, showing where they were made. We did not expect, therefore, to find that several pipes in this small sample come from ceramic centers that were (and are) famous for high-quality, high-status products.

Even more surprising are a pair of pipe bowls in the collection of the Asian Archaeological Comparative Collection in Moscow, Idaho. Both are from Chinese American sites in the region, and both bear inscriptions that read "Foshan Deji" -- "De (Virtue) Shop, Foshan.” Foshan, a city and sub-district just south of Guangzhou, includes Shiwan 石湾 (Cantonese: Shekwan), whose kilns were famous for making a low-fired buff- to reddish brown stoneware that competed with the Yixing kilns in eastern China in sculpture, desk equipment, miniature landscape items, and upscale flower pots. Shiwan was certainly capable of producing opium pipe bowls that would have competed with those from Yixing. However, actual Shiwan pipe bowls seem to be rare in China -- so far, we have not found them mentioned in the Chinese-language literature on opium. And yet, here are not one but two examples from sites in the United States. It would seem that excavations in North America can reveal facts about Chinese history that are little known in China itself.

The collection of the North American Pioneer Chinese Virtual Museum in British Columbia includes at least two pipe bowls from Yixing itself. One came from a cache of opium paraphernalia found sealed behind a wall in the former Wing Sang store in Vancouver's Pender Street Chinatown. The fact that the material had been hidden so carefully indicates that this example dates to the period when smoking opium was illegal in Canada (i.e., after 1908). The other Yixing pipe bowl was found at a historic Chinese habitation site. It appears to have been used and may be earlier than the other.

Yixing pipe bowl with Pan Shun Xiang trade mark, from Vancouver

The other side of the same Yixing pipe bowl, with composite character logo

Top to bottom, left to right:

"Shun Xiang Pan Shun Xiang"

Shiwan pipe bowl excavated in the U.S. -- one of the first ever identified (AACC Coll.)

A second Shiwan pipe bowl excavated in the U.S. (AACC Coll.)

Right to left. Top "Foshan;"

Bottom "De ji"

1929 A Fashionable Young Lady Gets Caught with a Half-Ton of Opium

三藩市副領事高英夫人廖氏私運煙膏入美

Most serious opium smuggling was done by Caucasians who bought the refined opium from wholesalers/refiners (always Chinese) in a foreign country (usually Canada), brought it clandestinely over the border, and sold it to distributors (mostly Chinese). The Caucasians might have owed money to their Chinese suppliers or buyers but were not working for them. White smugglers put up their own money, took their own legal and financial risks, bribed rheir own customs officials, and earned the profits of real middlemen, not the wages of mere employees or "mules."

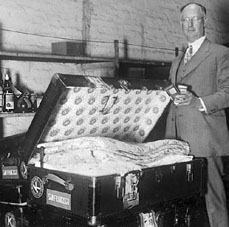

In only a few recorded cases did Chinese do the actual smuggling. By far the best publicized of these cases was that of a westernized upper-class lady, Suzy (Sui'e) Ying Kao. Time Magazine reported the story in this way:

"Returning last week from the Orient with its usual July load of tourists, plantation owners, white scientists, dark Oriental traders, the S.S. Tenyo Maru steamed through the Golden Gate [on July 9, 1929]. Watching the San Francisco skyline was a young Chinese woman--Mrs. Sui'e Ying Kao, wife of the Chinese Vice Consul at San Francisco. She was returning from a visit to her homeland. When the liner docked she, a lady of some importance, requested courtesy-of-the-port, that her baggage might be passed and delivered at once. She pointed to the imposing official seals that marked each of her seven wardrobe trunks and four suitcases, claimed diplomatic immunity. The Customs men communicated with the State Department, which verified their belief that diplomatic immunity is granted only to ambassadors or ministers and their wives, not to vice-consular ladies. Promptly the agents broke the seals, opened the trunks, lifted out laces, silks, and many a small tin box. The tin boxes contained a substance which the Customs men instantly recognized as opium--about $600,000 worth at current U.S. prices.

"Young Mrs. Kao, high born and college-bred, daughter of the Chinese Minister to Cuba, expressed polite surprise. The tin boxes, she explained, had been placed in her trunks by influential friends in China, to be carried as gifts to other influential friends in the U.S. Asked who these friends were, she refused to tell. She would be killed surely if she did, she said. She had no explanation at all about some documents which, found with the opium and translated, indicated that she was to have received $23,000 upon delivering the tins to the "influential friends."

The searchers found a total of 2,300 cans (about 1,000 pounds) of opium in her baggage, making it a very large seizure by contemporary standards. Suzy Ying Kao may have been an amateur but was a big thinker anyway. Collector Beecher's haul of 3,033 cans back in 1885 broke all records (see above). Mrs. Ying Kao's 2,300 cans did not quite equal that but was still enough to put her into the big leagues of opium smugglers.

John Toland, a Customs official, with one of Suzy Ying Kao's trunks. In his hand are two oval opium cans

"Heh-ven never stopped conversing, but his hands were busy and his eyes were fixed on what he was doing--knitting, I thought at first, wondering why nobody had ever mentioned that this craft was practiced by Chinese men. Then I saw that what I had taken for yarn between the two needles he manipulated was actually a kind of gummy stuff, dark and thick. As he rotated the needle ends about each other, the stuff behaved like taffy in the act of setting; it changed color, too, slowly evolving from its earlier dark brown to tan. At a certain moment, just as it seemed about to stiffen, he wrapped the whole wad around one needle end and picked up a pottery object about as big around as a teacup. It looked rather like a cup, except that it was closed across the top, with a rimmed hole in the middle of this fixed lid. Heh-ven plunged the wadded needle into this hole, withdrew it, leaving the wad sticking up from the hole, and modeled the rapidly hardening stuff so that it sat on the cup like a tiny volcano. He then picked up a piece of polished bamboo that had a large hole near one end, edged with a band of chased silver. Into this he fixed the cup, put the opposite end of the bamboo into his mouth, held the cup with the tiny cone suspended above the lamp flame, and inhaled deeply. The stuff bubbled and evaporated as he did so, until nothing of it was left. A blue smoke rose from his mouth ...." [Note 1]

San Francisco opium smoking scene, Harper's Weekly, 1888

Banning Opium and Curing Addicts

Turning Point: the 1909 Shanghai Conference

首次万国禁烟会在上海汇中饭店举行

The international conference held in Shanghai in February 1909 was heralded as (and may have really been) the single most important event in the history of effforts to ban the international trade in opium. Held in Shanghai to acknowledge China's spectacularly successful, if short-lived, efforts to suppress narcotics use, especially the smoking of opium, the conference brought all of the major national players to the same table and, in the glare of unprecedented international publicity, forced them to commit to eliminating the opium trade and opium use.

The conference was not seen as important by all white North Americans. However, it was noticed by many small-town newspapers, including the Winnipeg Free Press (1909/01/02), the Logansport [Indiana] Pharos (1909/03/02), he :Laredo [Texas] Weekly Times (1910/07/10), the Fort Wayne [Indiana] Sentinel (1910/07/08) and Journal-Gazette (1910/07/10), the Syracuse [New York] Post-Standard (1910/12/13), the Brownwood [Texas] Daily Bulletin(1909/03/09), the Portsmouth [New Hampsiire] Herald (1909/08/23), and the Nebraska State Journal (1909/01/31).. Many saw the conference as much more relevant to far-off China than to their own home towns.

The New York Times assigned a higher priority to the Shanghai Conference.than did most other North American newspapers. On February 7 1909 it gave the subject a full-page seven-column spread. By contrast, on February 12, the Oakland (California) Tribune gave it only three inches of a single column on page 12.

One more or less direct effect was to convince the United States Congress that the time had come to enact a serious anti-opium law. The one passed that year became the foundation of all subsequent anti-narcotics efforts in this country and helped to convince other countries that similar laws were imperative.

An authoritative summary of the conference and its effects will be found in A Century of Drug Control, issued in commemoration of the Shanghai Conference by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

Addiction Cures Aimed at North American Chinese 西北角华人戒烟有药

These are two of the many advertisements that appeared in the North American Chinese-language press extolling the virtues of over-the-counter medicines purporting to help opium addicts cure their habits. That the medicines

actually worked seems questionable -- as was true of similar medicines in China, many must have contained opiates themselves. However, such ads do show that addicts often were not happy with their dependence on opium, and eager to break the habit.

Left: 1900 Dec 20, San Francisco's Chungsai Yatpo, - 李兼善堂烟丸, Li Jian Pills. $7.50 each ‘liang’, will quit within 10 dosages or less than 1 liang, pills contain no [opium] “ashes”. At Jilan Tang Co., 37 ½ Waverly Place, San Francisco.

Right: 1920 Feb 27, Vancouver's Dahan Kungpo (Chinese Times) 大漢公報 – Renshou Tang Quit-Smoking Tea, $2.75 each. Produced by Changsheng Co. of San Francisco. Vancouver agent: Shenglong Chan.

Curing Addicts and Outlawing the Opium Trade: The Missionary Connection

In the English-speaking world, much of the pressure to ban opium and to cure addicts, sometimes through incarceration or worse, came from missionaries working in China and among overseas Chinese. The most radical anti-opium missionaries tended to be British, American, or Canadian Protestants as well as their Chinese converts, some of whom--as in Quirmbach's book--also became religious professionals. Other parts of this website will explore the controversy surrounding the propaganda and legislation spearheaded by those missionaries as they affected North American Chinese. For now it is enough to note that there was a strong religious element in anti-opium campaigns, that intolerance and righteous exaggeration were the inevitable result, and that in spite of this, Chinese everywhere owe a debt to Christian churches of the late 19th-early 20th centuries for supporting Chinese efforts to outlaw opium use and for campaigning successfully in the West to end the legal international trade in opium.

A. P. Quirmbach, From Opium Fiend to Preacher, the Story of Cheng Ting Chiah,Toronto, 1907. Image from Stevechasmar's Flickr site.

Bottom of another Yixing pipe bowl with the same trade mark text, "Shun Xiang Pan Shun Xiang," from a historic Chinese mining site in British Columbia

Brand Dominance in the Opium Pipe Bowl Trade

High-end pipe bowls may have come from famous ceramic centers, but those represented only a small fraction of the bowls in use by American Chinese. Cheaper pipe bowls could have been made almost anywhere. The makers only needed suitable clay, which cannot have been all that scarce, along with basic potting and firing skills to turn out a product that most opium smokers, except perhaps the true connoisseurs, would have found acceptable. It comes as a surprise, therefore, to find that the North American pipe bowl market seems to have been dominated by a single manufacturer, one that used the brand name Fu Ji or "Fortune Shop." Based on the limited sample we have seen, as many as one-third to one-half of the pipe bowls at excavated North American sites, from southern California to northern British Columbia, were made by the owner of the Fu Ji brand.

How was it possible for one among many Chinese makers of a relatively inexpensive commodity to have achieved such dominance in a distant market? Was the Fu Ji product similarly dominant anywhere in China? Were exports somehow tied to sales of the Yen Wo consortium's brands of opium, which as noted above, achieved a very high level of acceptance among North American Chinese consumers?

Fu Ji pipe bowls tend to be circular in plan, made from a solid gray or grayish brown stoneware clay, and decorated only with a few incised rings plus a distinctive trade mark in the form of several seals pressed into the clay while soft. In its simplest form, the overall mark resembles a cartoonist's fat baby flanked by a pair of oval seal stamps, each with the vertically arranged characters "Fu Ji":

More complex versions look less like a baby and help us to understand what they meant.

These complex versions bear the same inscription as the simple ones, plus a surname "Zheng" at the upper center and two or three Chinese coin symbols flanking and perhaps above the surname

The example on the left is the most elaborate we have seen so far. Exceptionally clear, the characters are:

[coin] zheng (a surname) [coin]

fu (fortune) lan (lotus) bian (edge) shui (water) fu (fortune)

ji (shop) sheng (voice) sheng (voice). ji (shop)

Here sheng is written in its long form; on the others it is written in the alternative short form, with the same meaning. The three central characters are read right to left: "water edge lotus."

The carefully made, simpler inscription on the right has exactly the same text: water edge lotus / voice voice, with "voice" (sheng) written in the short form.

Sheng sheng and shuang sheng ("double voice") appear on pipe bowls seemingly made by other manufacturers. Perhaps the term denotes a good quality of ceramic, fired to a high enough temperature for it to become partly vitrified, so that it makes a clinking sound (or "voice") when tapped. The number of coin symbols, one, two, or three, might have indicated the relative fanciness of the pipe bowl. Shui bian lan and fu ji seem to be trade marks, the first a poetic expression and the second one of the names of the manufacturing firm. Zheng must be the surname of the firm's owner. To the editors' knowledge, no other kind of traditional Chinese artifacts bears such elaborate commercial marking. Yixing tea wares, for example, also have impressed makers' seals, but usually no more than one. Pipe bowls, made of similar clay, may have five or more such seals.

1. Excavated in central British Columbia

2. Excavated in Los Angeles, California

3. Excavated in Port Townsend, Washington

4. Excavated in Los Angeles, California

Overall view of pipe bowl #3

5. Excavated in central British Columbia

Overall view of base of bowl #5

6. Excavated in central British Columbia

Overall view of base of bowl #1

Note: bowls 1, 5, & 6: Reg's British Columbia collection (http://www.chinesecol.com/); bowls 2 & 4: USC libraries (Chinese Historical Society of Southern California) Union Station excavation material, UPT 8367 & UPT 7151; bowl 3: display collection at Port Townsend (WA) Antique Mall, excavated there in 1980s.

1893 "The Pretty Smuggler and her Pathetic Story"

That was the headline of an item in the Port Townsend Leader, on August 31, 1893:

"Hattie Stratton ... , the woman caught red-handed Tuesday while in the act of smuggling contraband opium into the United States, did not spend last night in jail. Out of consideration for her sex, Deputy United States Marshal Lee Baker permitted his fair prisoner to remain at his house, and today another attempt will be made by the girl to raise her bail bond...

"Opinion at the custom-house appears to differ regarding the case. The prisoner's story, said to have been told in some quarters, is that her father and brother are dead and that a sister and her mother are incurably ill, hence she became a smuggler to prevent those of her family who are still in the land of the living from meeting death by starvation.

"This view of the case is scouted by nearly the whole force of customs inspectors. Will Learned is certain that she is an expert smuggler, not at all adverse to taking her chances with the world at large. In this she is backed up by most of the Kingston's [a steamship, the City of Kingston--eds.] officials. The gushing and sloppery [sic] attempt at sentimentalism in the premises displayed by an alleged local reporter, the people about the custom house have only the most profound contempt for.

" 'Why,' said an inspector, who for obvious reasons does not care to have his name mentioned, ' the fellow who wrote that rot is simply the softest and most thick-headed gull I ever heard of. A woman to smuggle opium must go into the purlieus of Chinatown at Victoria and the vice of Chinatown at Seattle. Would a decent woman do that? I guess not. This woman may be all right, but the prospects of a life of shame never drove her to smuggling...' "

Hattie's mother, then living in Puyallup, told the Leader on September 10 that "Hattie is a noble girl and nothing but absolute necessity would have caused her to enter into this business." She went on to express gratitude to Deputy Marshal Baker for allowing Hattie to stay with him, which could indicate that the Marshal's and Hattie's relationship was perfectly proper, despite the insinuations of the Port Townsend Customs staff.

Impartial readers may conclude that neither Hattie nor her critics were above reproach, and that the Leader's reporter was not the most literate writer in the history of Northwestern journalism.

Port Townsend was not always hostile to pretty ladies. This statue was erected in that city, next to its Chinatown, in 1906

An article in the Victoria Daily Colonist (May 8, 1888) takes the story further. In 1882, the Yen Wo and Wo Hang companies merged and bid successfully for the "farm" or legal monopoly of opium in Hong Kong, now calling themselves the Sing Wo Co. Thus the two former rivals gained for themselves one of the most profitable commercial concessions in history—full economic control of the India-China opium trade, almost all of which originated in British India and passed through British Hong Kong before onward shipment to Chinese distributors.

This happy state of affairs lasted only four years, however. In 1886, an entirely new syndicate backed by wealthy Singaporeans, the Fook Tuck Co., managed to outbid Sing Wo for the Hong Kong monopoly. Sing Wo was forced to leave Hong Kong and set up shop in the nearby Portuguese colony of Macao.

The ousted firm was far from dead in spite of this. First, it was still immensely rich. Second, it owned all of the top opium brands: Fook Lung and Lai Yuen as well as Hop Lung and Wah Hing. And third, it had already begun to diversify by establishing opium “factories” (i.e., refineries) in other places, among them Victoria in British Columbia.

Another section of this page sketches the history of Victoria’s Sing Wo Chan Co. For now, what matters is that the transplant was only moderately successful in spite of fiercely competitive pricing, and that imports of Sing Wo’s Asia-refined brands kept going strong. Even after the importation and sale of smoking opium became illegal in 1908-9, North American addicts continued to pay premium prices for Fook Lung and Lai Yuen.

Function dictated the basic design of opium lamps. They had to be low enough to be used in a reclining position while the pipe bowl was tilted over the flame, and they had to focus the flame so that the opium would be vaporized while the pipe bowl stayed fairly cool. It was also desirable, although not absolutely necessary, to have the flame be visible so that it could be adjusted to an optimum height and temperature. Due to these requirements, most lamps had squat bases and glass chimneys that were were short, thick, and tapered toward the top. The opening at the top of the chimney was much narrower than in the glass chimneys of the ordinary oil lamps that in Europe and North America, and even in the richer parts of Asia, served to illuminate 19th century homes.

Opium Lamps in North America

The lamp shown above was bought for a low price in a Seattle area antique mall. It has "Made in Hong Kong" stamped into its brass base, and must date to the late 1940s through 1960s. Glass filled with tiny bubbles, as in the chimney of this lamp, was typical of the cheaper products of Chinese glass factories until quite recently. Readers who doubt that those factories could do better should click here to see one of the finest glass opium lamps ever in North America. It was formerly in Los Altos, California, owned by an art dealer rather than an opium smoker.

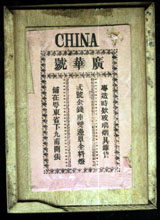

The following picture is of two higher-quality glass chimneys for opium lamps. They came from the same historic shop in Vancouver's Chinatown that yielded the Yixing pipe bowls shown elsewhere on this page. One, when acquired by its present owner (see http://www.chinesecol.com), was packed in its original box with a label--a rare prize, as lamps, unlike cans and pipe bowls, usually are not inscribed with the names of places, makers, or stores.

The Chinese text on the label reads as follows:

top line: "Canton China Store" [Guang Hua Hao]

left column: "Specialists in fashionable glass, accessories, and opium equipment"

center column: "Grade 2, coin-design base, double chimney, all-glass lamp"

right column "Our store is in the capital of Guangdong [i.e., Guangzhou or Canton], in Xiajiupu district"

One of the lamps is a big single-chimney lamp that came in the cloth-covered box behind it The other, described by the label, came in the wooden box on the left. It has a double chimney--that is, with a chimney-shaped glass oil reservoir with wick holder inside the chimney itself--and a glass base that somewhat resembles a traditional Chinese coin. The oil reservoir and wick holder do not show in the picture.

While such bases seem not to be common in historical collections in Asia, they occur frequently in North American archaeological contexts. In fact, Reg of the NAPVM (see below) says they are just about the only kind that is known to have been used by ordinary opium smokers on this side of the Pacific: "In all the opium layout pictures from North America, and the opium paraphernalia confiscation pictures those plain glass lamps of various shapes are the only lamps you see. I've never seen ANY of the lamps with metal bases that are so commonly offered on Ebay as opium lamps. And these are found in the opium museum collections of fancy layouts."

Not at all Shocked. The Governor-General's Wife Visits a BC Opium Factory

| ||||

Lady Aberdeen in the 1890s

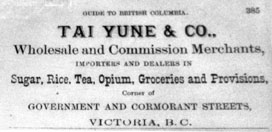

Tai Yuen (or Yune) ad in Guide to British Columbia, 1877-78

In view of Lady Aberdeen's plain statement, not to mention the large sums regularly collected as customs duty on opium imports (about $140,000 per year in the early 1890s, plus license fees, fines, and miscellaneous income), we may assume that all high-ranking officials in the national capital, Ottawa, knew about Victoria's opium industry and that most of its production was smuggled into the United States. And yet future premier Mackenzie King would later express surprise that the industry existed. As noted in the previous section, he also pretended not to have known about the smuggling.

David Lai (note 1) quotes her description of their Chinatown tour:

"...our first visit was to Tai Yuen, an opium refiner. We were shown all the processes from the time it was brought [from India] in its raw state, made up into balls the size of the cocoa nut, covered with a mass of dried opium leaves. Then it is split open, put in pans and boiled and stirred and left to cool, and then boiled again. Up to a year ago a great deal of opium was refined here for the purpose of smuggling it into the United States."

Lady Ishbel Gordon Aberdeen, intellectual, social reformer, and wife of the Governor-General, visited Victoria with her husband, the Earl of Aberdeen, in 1895. She and the Earl already knew a good deal about British Columbia, having owned a ranch in the Okanagan Valley for a number of years. On the agenda for their time in Victoria was a tour of Chinatown and of an opium factory, the old and well-known Tai Yuen & Co., at the corner of Cormorant and Government Streets.

Note 1: The quotation and much of our data come from the authoritative study by Dr. David Chuenyan Lai, "Chinese Opium Trade and Manufacture in British Columbia, 1858-1908," Journal of the West, 1999, vol. 38, No. 3, pp 23-26.

Note 2: The can (RBCM 974-86-1) belongs to the Royal British Columbia Museum. It was shown to the editors by Dr, Lorne Hammond, that museum's curator of history and a leading student of Canadian Chinese material culture. The image appears here with the RBCM's permission.

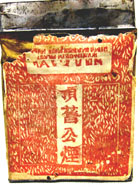

One of Tai Yuen's opium cans with its original label. The top two lines are in mock English. The third line, written very badly, reads "Tai Yuen." The vertical Chinese characters read "Top Grade Aged Permit Opium." The term "permit opium," also used in China, seems to refer to certification by the colonial government in Hong Kong that taxes due on opium imported from India have been paid, implying that this batch of opium is the genuine Indian product. See Note 2.

Bow Yuen. 寶源 [PY: Bao Yuan] 1884-1889

Chu Chung, & Co. 兆昌 [PY: Zhao Chang] 1882-1899

Chung Chung & Co. 1901

Fook Yuen/Yen & Co. 福源 [PY: Fu Yuan] 1884-1896

Hip Lung & Co, 協龍? [PY: Xie Long] 1889-1901

King Tye Co. 乾泰 [PY: Qian Tai] 1884-1892

Kung Wong On Lung & Co 1901-1908

Kwong Chung & Co. 廣昌号[PY: Guang Chang] 1883-1889

Kwong Lee & Co. 廣利 [PY: Guang Li] 1860-1904

Kwong Lung Hing? [PY: Guang Long Xing] 1886-1889

Kwong On Lung & Co. 廣安隆 [PY: Guang An Long] 1884-1924 (Click here for partial

Kwong On Tai. 廣安泰 [PY: Guang An Tai] 1885-1890 (Click here for brand mark

Lun Chung & Co. 聨昌号 [PY: Lian Chang] 1881-1908

Quong Man Fung & Co. 廣萬蘴 [PY: Guang Wan Feng] 1894-1920, 20 Comorant St.

Shon Yuen, 信源 [PY: Xin Yuan] 1905-1926

Sing Kee & Co. 成记 [PY: Cheng Ji] 1889

Sing Wo Chan. 成和棧 [PY: Cheng He Zhan] 1886-1889 (Click here for brand mark

Tai Soong. 泰巽号 [PY: Tai Xun] 1862-1902 (Click here for brand mark on can)

Tai Yick & Co. 泰益 [PY: Tai Yi] 1889

Tai Yune/Yuen & Co. 泰源 号[PY: Tai Yuan] 1875-1908 (click here for paper can label

with brand name), 135 Government St.

with brand name), 135 Government St.

Yan Wo Sang 1860-1865

Yuen Kee & Co

Others mentioned in D. C. Lai 2010, p 38: Boon Yuen, Lee Chuck, Sam Kee, Siu Chang

Note: Romanized names are those used by these firms in English-language documents and advertisements.

Pinyin (PY) names are in parentheses. In some cases we do not know the names in Pinyin or Chinese characters.

Former opium "factories" on the N side of Pandora, formerly Cormorant, St.

Opium Pipe

OPIUM IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST 西北角鴉片煙

1850s-1930s -- Main Page

Making & Selling

Smuggling

Using

Banning & Curing

Coin-design base with glass oil reser-voir, RBC Museum, Victoria

Coin-design lamp base, Port

Townsend Antique Mall site

Examples of glass lamp bases occur at many North American Chinese sites. Two such bases are shown here. One, looking rather like an old-fashioned movie film reel, was excavated during the building of the Port Townsend Antique Mall. The other is from the collection of the Royal British Columbia Museum, inventory # 965-6038-1ab. There are several more in the Asian American Comparative Collection in Moscow, Idaho. The one shown with its box, two paragraphs above, appears on the website of the North American Pioneer Virtual Museum

Other Yixing pipe bowls with the same maker's mark also turned up in the Wing Sang cache, proving that producers included bowls of varying shapes in the same shipments. The three shown here are in the Chung Collection at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Like the Pioneer Chinese Museum's bowls, they bear the characters "Shun xiang" 吮香, repeated twice with the name "Pan" in the center. The characters form the trade mark of an Yixing opium pipe bowl maker who seems to have been formerly well known--the same mark appears on pipe bowls shown on Chinese-language websites. Pan's mark is probably intended to imply a connection with the most sought-after of all Yixing pipe bowl makers, "Xun Ming" 允鸣. The presence in British Columbia of such upscale pipe bowls comes as a surprise. Evidently there were smokers in the province who not only could afford such bowls but whose fellow smokers were capable of appreciating the owner's refined tastes.

Three newly discovered (as of 11/09) Yixing pipe bowls in the Wallace Chung Collection, UBC-Vancouver, where they were shown to the editors by Sarah Romkey, Archivist.

Enlargement of composite logo, Chung Collection\.

Why should we have a page on opium? Isn't it a disgrace, a dark passage in Chinese-American (and Chinese) history? For the reason why, click here

The Chinese press in San Francisco expressed outrage, and the local branch of the Guomindang party demanded that she be sent back to China for punishment immediately. C. S. Wu 伍朝枢, the Chinese Minister in Washington, concurred and asked Secretary of State Stimson to extradite her. After only a few days of consultation, Stimson granted Wu's request. Mr. and Mrs. Ying Kao along with Suen Foon 孫垣, a wealthy advisor to the San Francisco consulate and the probable instigator of the smuggling scheme, were on their way back to China by the end of the month. The trials were held in September 1929. The three received prison sentences ranging from four to six years.

Sources: Time Magazine 7/22/1929 issue; New York Times 7/11, 7/12, 7/`13, 7/13, 9/7/1929, and 2/4/1930 & 10/8/1930 issues; image from Stevechasmar’s Flikr site, http://www.flickr.com/photos/opiummuseum/sets/72157601035562361/

Suzy and her husband appeared in news stories nationwide -- here, the New York American

Fook Duk

Hong Kong Central

Chi Wo Cheung

01/18/10 -- Reg has just sent pictures of two unfamiliar opium can inscriptions. Both are said to have been found at a Chinese railroad camp in the Grants Pass area of Oregon. Fook Duk (Mandarin "Fude") is now known to be another Hong Kong brand (click here); there are others from Queensland in Australia and in the Asian American Comparative Collection in Moscow, Idaho. The Chi Wo Cheung (Mandarin/Pinyin Zhihe Xiang) example is unique. It is the first can we have seen that purports to come from Central, the main business district of Hong Kong

版权 Copyright is free for non-profit use: : click here for more information

Victoria: The Largest Opium Making Center Outside Asia

域多利 - 加拿大最大的鸦片烟产地

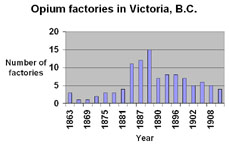

Modern cruise ship passengers find Victoria to be charming, beautiful, and quite British. Few of them suspect that between 1860 and 1908, it was the opium capital of the New World—in fact, the largest opium refining center outside Asia. The most important research on Victoria opium is that of David Chuenyan Lai (see citation below); his advice has been central to our understanding of the subject.

Most recorded opium “factories” (i.e., refineries) in Victoria opened in the 1880s. The number peaked in 1889, when there were 15 on Cormorant, Government, and Fisgard Streets in Victoria’s Chinatown. Opium refining seems to have gotten its real start in Canada after 1880, when a new U.S. law restricted opium refining to American citizens (Culin 1891: 499). This caused would-be Chinese refiners, none of whom by law could become U.S. citizens, to move across the border to Victoria, which then held the largest Chinese community in Canada. The new industry took off and proved to be reasonably profitable (for a new view of opium profits, click here), both for refining companies and for the national and local governments. The refining of smoking-type opium was not banned in Canada until 1908. Before then, refining and selling the drug in Canada was no more illegal than distilling whisky in Scotland.

All Victoria opium factories were owned and run by Chinese, although their main customers, large-scale smugglers, were overwhelmingly white. The industry generated a lot of tax money, which may be why the national government was slow to close it down. In 1865, a license fee of $100 was imposed on each seller of smoking opium; sellers of opium-containing patent medicines, all of them white, were exempted (Lai 1999: 22). The cost of a license had risen to $250 by 1886 (Lai, same). In 1868-1871, the duty on imported raw opium was 25% (City Directory 1868: 2058). In 1891 the peak year for customs duties on raw opium to be made into smoking opium, the revenue to the Canadian government was more than $140,000 (Lai, same). In 1884, when the city began to see a leap in the number of opium factories, 28 Chinese workers were refining opium (CCBA 1960, p. 58). More than a hundred still worked in Canadian opium factories, mostly in Victoria, in 1908 (Colonist 1908-07-14).