| ||||

| ||||

Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee (CINARC)

CHINESE WOMEN IN THE NORTHWEST

西北角的红粉佳人

Women from China began to arrive in California in the 1850s, and reached the Pacific Northwest a decade or two. After that they began a long journey of adjustment.

These early Chinese-American women have traditionally been seen as helpless victims, brought from China without skills or consent and forced to become prostitutes or low-status wives. However, we think that view must be reexamined. Many female Chinese immigrants were not at all helpless. In the Pacific Northwest, as in other parts of the Americas, they overcame enormous personal obstacles, built bridges to the larger American society, and contributed greatly to their gender-skewed Chinese communities.

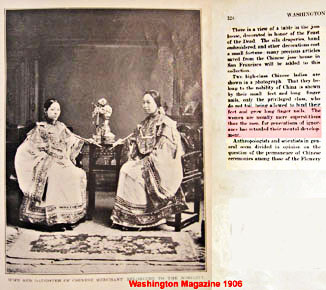

"Retarded Mental Development" 脑袋瓜不发达?

The editors couldn't resist this one as an example of sheer outrageousness. The picture is from a 1906 article in the shortlived Washington Magazine. The text reads in part, "The women are usually more superstitious than the men, for generations of ignorance has retarded their mental development."

The two ladies in the picture, who do not look noticeably retarded, may have been Californians. In spite of the magazine's name, the author of this article was not writing specifically about Washington Chinese.

版权 Copyright is free for non-profit use: : click here for more information

When 12-year old Maggie (Margaret) Chin arrived from Hong Kong to Seattle on April 2, 1909, she wasn’t sure she would be admitted, although an American citizen. The Immigration Bureau's inspectors, probably instigated by their boss, the virulently anti-Chinese labor leader Terence Powderly, were especially harsh toward Chinese women immigrants at that time. The fact that Maggie was with her mother, Dong Oy, a native-born Chinese American, should have helped. But Dong Oy too expected problems, and not all were political.

Dong Oy had been born in San Francisco (and thus was an American citizen) and gone back to China with her parents as a teenager. At the age of 17, while still in China, she married a young Seattle-born man named Chin Lem (陳霖; pinyin: Chén Lín, also called Chin Tue Dong). He too was a U.S. citizen and, even better, the son of Chin Gee Hee (陈宜禧, pinyin Chén Yíxǐ), the richest and best-connected Chinese businessman in the Northwest. Maggie was born in 1896. Her father left for Seattle soon afterward and was followed by Dong Oy and Maggie when the girl was five. They stayed in Seattle until she was ten, after which the whole family went back to China, after a reception in Dong Oy's and Maggie's honor at the home of Mrs. Janie Bigelow of the First Presbyterian Church Missionary Society [Note 1a]. The family may have gone because Chin Gee Hee wanted them to [Note 1b]. He had already been in China for several years, completing construction on his Sun Ning Railroad (新寧鐵路; pinyin: Xīnníng Tiělù). Conceived, financed, and built by Chin, it was the first all-Chinese railroad in the history of China.

Good looks, plenty of money, privileged political status, and talent in the family--the Chins seemed to have it all. But their marriage was not happy. Because Dong Oy had not produced a son, Chin Lem decided (in spite of a written agreement with Dong Oy, signed before they left the U.S. for China) to take another wife. The apparently perfect marriage became a sad arena for domestic strife.

When Chin Lem breached the agreement and began looking for a second wife, Dong Oy refused to stay in Hong Kong. She found the money for steamship tickets for her daughter and herself. However, her husband took the money and disappeared. She was forced to go instead to her father-in-law's home town, Sunning (modern Toisan or Taishan). There she found herself a virtual prisoner. Both wife and daughter suffered in Sunning, physically as well as mentally. Moreover, Chin Gee Hee tried to discredit Dong Oy with the American authorities by accusing her of prostitution: As Amos Wilder, Consul-General in Hong Kong, informed John Sargent,Immigration Inspector in Charge at Seattle, "The father in law seems to be prejudiced against his son's wife Dong Oy with charges that she was formerly in a house of ill fame." [Note 1c]

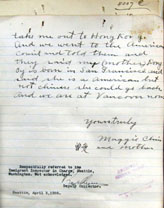

Dong Oy and Maggie escaped from Sun Ning. Doug Chin writes that Chin Gee Hee ordered a watch to be kept for them at Chinese ports and railroad stations, but in spite of this they managed to get back to Hong Kong [Note 2]. Her flight was seen as rank desertion by her husband and his family. They not only withheld her passport and other identification papers but tried to bar her from entering the U.S. Three days after Dong Oy and Maggie were admitted at Seattle, the acting inspector in charge, Henry Monroe, received this telegram from Hong Kong:

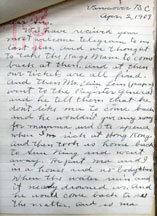

Luckily for Dong Oy and Maggie, they had the support of the U.S. Consul in Hong Kong as well as of two strong-minded missionary ladies there, Miss Pitman and Miss E May Law. But even this might not have been enough to get them back into the U.S. without papers to prove their citizenship. What seems to have turned the tide was Maggie. Although Dong Oy was illiterate and spoke only broken English, Maggie was different. At the age of twelve, with only five years of schooling in America, she drafted this petition while she and her mother were waiting in Vancouver for admission to the United States [Note 4]:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

General Note: The Maggie Chin story was first discovered by Seattle historian Doug Chin. We owe him thanks for calling our attention to it.

Note 1a Seattle Times 1907-09-11

Note 1b Prather gives a good summary of the Dong Oy and Maggie affair. He accepts Ruthanne Lum McCunn's idea that Chin planned to have both of them killed after they reached China. See William N. Prather, 1996 "Sui Sin Far's Railroad Baron: A Chinese of the Future." American Literary Realism, 1870-1910, Vol. 29, No. 1 pp. 54-61

Note 1c. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Pacific- Alaska Region, Chinese Exclusion Files: RS 17824-5, Wilder to Sargent, 1908-10-09. Charges of prostitution were normally enough for Immigration to bar Chinese women from landing in the U.S. (See Ted Stevens, "Tender Ties," Law & Social Inquiry, 2002, vol 27, 2: pp 271-305).

Note 2. Doug Chin, Seattle's International District, the Making of a Pan-Asian American Community (2nd Edition), 2009 . Seattle: International Examiner Press, p 44. Doug tells us that his main source for Dong Oy's troubles in Hong Kong and Sunning was an article by Gudrun Anderson in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer,1917-09-23. We have not seen the article yet but believe it to have been based on interviews with Dong Oy herself.

Note 3. NARA Chinese Exclusion File RS 17824-5, Monroe to Edsel, 1909-04-07

Note 4. ibid., Maggie Chin to Immigration Service, 1909-04-02

Note 5: ibid., Sargent to Bigelow, 1908-06-25

Note 6. Daniel J Keefe to Secretary, Bureau of Immigration, 1912-02-14. NARA Chinese Exclusion Files RS 28678.

Note 7: Seattle Times 1915-04-24

Note 8: Doug Chin 2002, p 44.

"Wife and daughter deserted in March 1909. Heard they arrived at Seattle. Deport at once. If more information required inquire Quong Tuck firm [Chin Gee Hee's company-eds.] [signed] Chin Teu Dong (Chin Teu Dong is commonly nown as Chin Lem)" [Note 3]

Maggie's ability to write nearly grown-up English and her fluency in the spoken language when answering officials' questions seems to have impressed the Immigration officials. Their favorable decision was at least partly due to her verbal skill as well as to Dong Oy’s persuasive story, pleasant personality, and foresight in acquiring such valuable American allies while in Hong Kong.

Vancouver BC

April 2, 1909

Dear Sirs

We have received your most welcome telegram to us last year, and we thought to take the Kago Maru to come back at then, and at then our tickets were all fixed. And then Mr. Chin Lem (papa) went to the Register General and he tell them that he don't like ma to come back and he wouldn't give any money for mamma and I to spend when I'm sick at Hong Kong. And then took us home back to Sun Ning and went away. He put mamma and I in a house and no-body there. When the water ruin and it nearly drowned us. And he would come back to see the matter. And so ma

take me out to Hong Kong. And we went to the American Consil and told them and they said my (mother) Dong Oy is born in San Francisco and said she is an American but not Chinese she could go back. And we are at Vancouver now.

Yours truly

Maggie Chin

and mother

The rest of what is known of Maggie Chin's story is well told by Doug Chin (not a relative, incidentally). Dong Oy took care of babies and sewed for a living. After Maggie had entered the University of Washington, she and her mother opened a Chinese tea room in the University District. Long-time Seattle Chinese who remember Dong Oy say that she remained fiercely independent for the rest of her life.

Women Who Were Not Down-Trodden: the Saga of Dong Oy and Maggie Chin.不倔不挠话曾爱

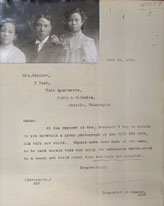

Dong Oy had had a rough time. Yet she did not act like a helpless victim. Indeed, as Chin Gee Hee and his son must eventually have realized, in Dong Oy they faced a truly formidable opponent. Ten months before returning to Seattle, she persuaded the U.S. Consulate in Hong Kong to make sure that Chin Lem's new wife would not enter the U.S. As this image shows, the Seattle Immigration office followed the Consulate's instructions by borrowing a photograph of Dong Oy, her husband, and Maggie, then copying and distributing that to border inspectors for use in case "this man [Chin Tue Dong/ Chin Lem] applies for admission accompanied by a woman and child other than his wife and daughter:" [Note 5]

Left to right: Maggie Chin, Chin Lem, and Dong Oy

> "Retarded mental development" 脑袋瓜不发达? 10/30/2010

> Women who were not down-trodden: the saga of Maggie Chin and Dong Oy 不倔不挠话曾爱 11/15/2010,

revised 03/30/2012

> The courtesan Que Qui flees to Portland 11/18/2010

> Suicide by opium 吞烟自杀 12/18/2010

加拿大保皇女会 : 域多利, 温哥华/二埠03/07/2011, revised 03/26/2012

1900年卑斯省教会妇女关心社会 03/13/2011, revised 03/27/2012

- 康同壁在西北角的活动 03/13/2011, revised 05/22/2012

> Lives of Chinese Women in the Pacific Northwest 07/05/2011, revised 03/14/2012

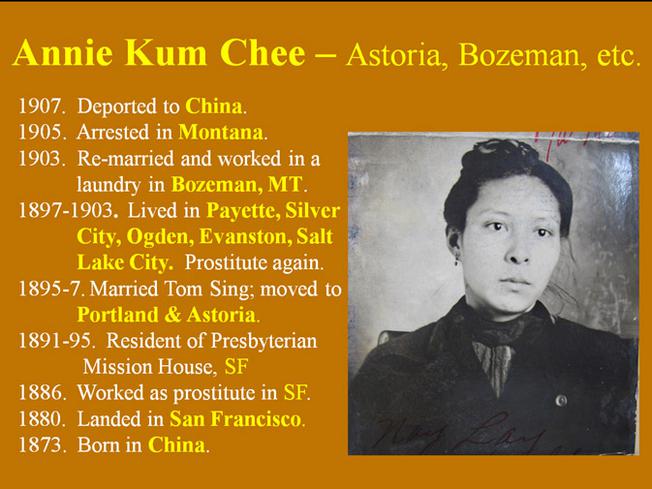

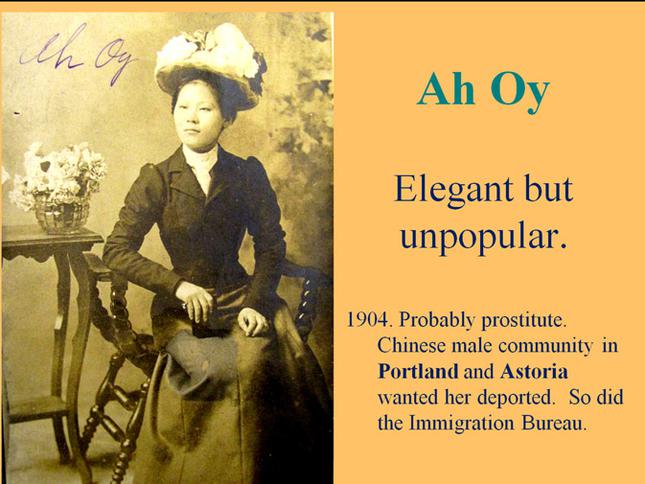

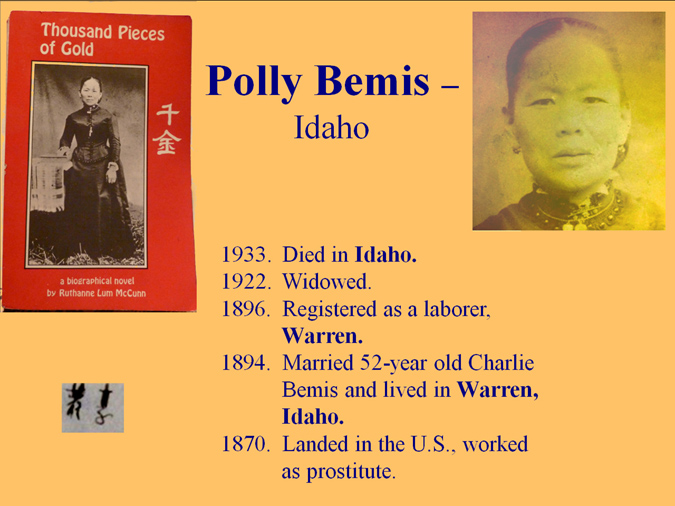

Prostitutes 娼妓: Soo Po Lan, Annie Kum Chee, Polly Bemis, Ah Oy, Mary Bong 03/14/2012, revised 11/22/2012

> Portland's beautiful, notorious Oi Sen 11/30/2013

A footnote to Dong Oy's pro-female attitude and her ability to maneuver within the American system: in 1912 she managed to bring her deceased brother's 12 year-old daughter, Bo Yue Dong, over from China. Although the girl's father, Fook Cheung, had been an American citizen (he died in the wreck of the steamship Ohio off the Alaskan coast in 1909), bringing a young Chinese woman into this country was exceedingly difficult in those days. However, Dong Oy was equal to the task. She seems to have enlisted the support of Senator Jones and Congressman Humphrey, as well as of her acquaintances in the Immigration Bureau. The girl came in easily, with only a brief delay in Vancouver [Note 6].

It is a bit surprising that Dong Oy chose to assist a niece rather than a nephew in entering the United States. Most Chinese women of that period would have given a much higher priority to male kinsmen. But then most women would also have submitted tamely to their father-in-law's decision for their husband to take a second wife, particularly when their father-in-law was as dominatingly important as Chin Gee Hee. Clearly, Dong Oy was nobody's

Immigration photo of Bo Yue Dong, 1911-12

Photo circulated by the Immigration Bureau to deny entry to Chin Lem's 2nd wife

The Courtesan Que Qui Flees to Portland

Not all American Chinese sex workers were common prostitutes, and not all were looked down upon by their Chinese clients or, for that matter, by other residents of the wide-open 19th century West Coast. Just as white courtesans like Lola Montez were accepted and even lionized by public opinion, so too were high-status Chinese courtesans treated with surprising respect by almost everyone. One famous case is that of Ah Toy, who became famous in 1850s San Francisco for her beauty and her business sense, eventually owning a whole chain of profitable brothels. For more, see the relevant Wikipedia article: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ah Toy.

Another, less famous, case is that of Que Qui in the 1890s. A reporter for the San Francisco Call, one Sarah Comstock, wrote a long, amusing article (click here) sketching Que Qui's colorful history, which included fame and fortune in San Francisco and a hasty flight to Portland in early January, 1902. According to Comstock, Que Qui wished to escape the attentions of influential admirers in California, one of whom was Jim Wong who later would be the chief concessionaire for the China Village exhibit at the Panama-:Pacific Exposition of 1915.

Photo of Que Qui from 1902 Call

Another note on Ah Toy. She has become a favorite of modern writers on ethnicity and women's issues. Although much of what they write about her is partly fictional, she -- like Que Qui -- did in fact exist. However she may not have been the joyful liberated woman that her fans describe. A brief note in the Sacramento Daily Union (1855-11-19) shows that the life of a Chinese American courtesan, celebrated or otherwise, was not necessarily a happy one.

MISS AH TOY. This celebrated Chinese courtezan [sic] tried to destroy herself on Thursday night in San Francisco by swallowing poison. She still lives.

Suicide by Opium 吞烟自杀

Chinese women in California and the Pacific Northwest were particularly susceptible to it. Click here for more details

Choy Susan

William Henry Bishop's short story with this title, first published in 1884 and said to have been translated later into both French and German, was one of the first fictional works in any non-Asian language to depict a Chinese woman as being a strong, independent person. Gruff, commanding, and tender-hearted, Choy Susan is the leader of a fishing village located about 100 miles south of San Francisco. Bishop seems to have been describing a real place -- probably the long-lasting Chinese fishing "camp" at the north end of what is now Cannery Row in Monterey.

"The village consisted of a main thoroughfare of wooden cabins, silvered gray by the weather, with a motley cluster nearer the shore of fish houses, strangely fashioned boats and tackles, and tall frames of poles along which were strung rows of fish drying in the sun. All was set down amid rugged bowlders as silvery gray as the houses. Bright little patches of color -- red and yellow papers inscribed with hieroglyphics, a gay pennant, a tasseled glass lantern, a carved and gilded sign scattered here and there through the whole -- might serve from a distance as a reminiscence of the once vivid spring wild flowers of the section now vanished from the brown dry pastures of midsummer."

"plainly a person much in the habit of being deferred to; and this, together with her need of defending herself against scoffers, of whom she had met with not a few among the Melican men in a long experience, had given her a manner bluff, masculine, and even surly. But she was amenable to kindness, and there were even moments when under her unsmiling exterior she almost seemed to appreciate the humor of herself "

Choy Susan herself is

Her foil in the story is a beautiful but silly Caucasian girl named Marcella who, though in love with a handsome young railroad surveyor named Easterby, is being forced by her Mormon father to marry an older fellow Mormon who, among his other shortcomings, is likely to take other wives. Marcella, in despair, confides her problem to Choy Susan. The latter comments,

"No good for woman to mally man with plenty otha wife," said Choy Susan with a philosophic air after a pause. "My makee big mistake myself."

"Ah?" The listener turned an attentive ear to sympathetic wisdom even from so rude a source as this.

"Yes You heap good lookee but heap good lookee can catchee alle same plenty bad time." Choy Susan meant, no doubt, that even great beauty may be coupled with a hapless fate, which we all know is true enough.

"My know how it was myself," she continued. "My tellee you My husbin name Hop Lee. My mally Hop Lee when my Jesus girl down Stocktin Stleet Mission. He Jesus boy too."

"Oh you were Christians, then?"

"One time. Not now. Hop Lee he say "You mally me I got heap big store, heap money. You no work sewin' m'chine. You catchee plenty good time. Plenty loafee. I no takee no more wife."

"He promised you not to marry again, then?"

"He plomise." The speaker closed one eye shrewdly then reopened it.

"Bimeby plitty click I get sick. Small pock. He say 'You no good. Shut up. I goin bling otha wife.'

He bling two more wife. They beatee me. Makee work sewin' m'chine alle time, alle time, alle samee likee slave."

"Poor Choy Susan"

"Yes. So one day I lun way. Catchee money and man clothes. Catchee railroad and goee Salt Lake City... then come here, get pardner, go fish, and kleep store."

"And what has become of Hop Lee?"

"He dead," said Choy Susan contemptuously. "I pray Jesus 'ligion first time makee Hop Lee die but it no makee him die. Then I pray China 'ligion makee die and China 'ligion makee die and both wife too, light away plitty click. China joss much more good. Jesus 'ligion no good"

The rest of the plot is as one would expect: after assorted vicissitudes, plus a convincing ethnographic description of a Chinese fishing village, Choy Susan contrives to bring the two young lovers in secret to her cabin just before the Mormon marriage ceremony is due to occur. In the cabin they find a Protestant preacher who, in spite of Choy Susan's pagan sentiments, seems to be a friend of hers. The preacher marries them just before the Mormon father and would-be Mormon husband arrive. They are discomfited, the fishing village is astounded, and the newlyweds are joyful.

" 'It's all Choy Susan's doing,' said Easterby, extending a friendly hand to the interpreter. 'And we hope Choy Susan will come and live with us when we settle down,' added Marcella sweetly."

We have no idea whether any of this is true. The romsnce of Marcella and her lover, not to mention the absurdly caricatured Mormons, are clearly fictional. But the details of Choy Susan's life and community ring true. Could Bishop have heard about someone like her while he was traveling in California during the early 1880s? Readers who wish to check the story for themselves should look at William Henry Bishop, Choy Susan and Other Stories, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1886. The full text is available for free on Google Books.

Chinese fishing boats in California, 1880s. From an article by W. H. Bishop, the author of "Choy Susan", in Harper's Monthly, 1883

Chinese Fishing Village in Monterey, from a California Historical Society photograph on the Library of Congress' American Memory website

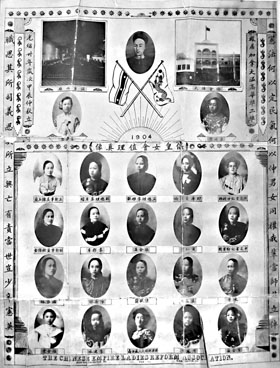

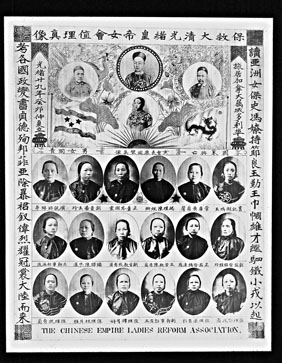

The Chinese Empire Ladies Reform Association in 1903-4: real or public relations fantasy? 加拿大保皇女会 : 域多利, 温哥华/二埠

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Baohuanghui (Chinese Empire Reform Association, CERA) in British Columbia produced two photo montages which, if they reflect reality, constitute the earliest visual evidence that Chinese women in North America had begun to form organizations of their own. Considering that in China, and overseas communities as well, women of the middle and upper classes had traditionally stayed in the background of public life and, indeed, rarely left their homes, the Women's Empire Reform Association would seem to have been a breakthrough -- evidence that the forces of progressive thought and western values had begun to change the way that Chinese Canadian (and, presumably, Chinese American) women related to the world.

Victoria 1903

Vancouver & New

Westminster 1904

Now, these pictures are not intrinsically implausible. Both Victoria and Vancouver (with nearby New Westminster) held a good many wealthy and sometimes progressive Chinese men. The ladies in the photos, who all are identified in captions underneath (see the next article), were the wives and daughters of those men. If such well-to-do ladies had been white or, if white, not married to Chinese men, they would have appeared often in newspapers as attendees at fashionable receptions and as organizers of charitable events. Moreover, we know that in San Francisco in 1902, the Baohuanghui or BHH had already sponsored a lecture by a patriotic Chinese girl, Sieh King King 薛锦琴, that was attended by many Chinese women in the company of their husbands and fathers [Note 1].

So then, what is wrong with these pictures? Several things. For one, other Chinese women's organizations did not appear in California, where most North American Chinese trends began, until the 1910s and early 1920s [Note 2]. The Victoria and Vancouver branches of the Women's Baohuanghui would thus have been surprisingly early. Another point. There is not a single mention of women at any BHH meeting or public event in any issue of the region's leading newspaper, the British Colonist of Victoria [Note 3]. This shows that the Ladies' Reform group cannot have been too active or long-lasting. And a third point. A similar picture commissioned by the BHH showing (male) members in another town was faked, showing that the BHH was not above using photos to misrepresent the nature of its local membership [Note 4].

A B C D E

0

1

2

3

4

The Ladies of the Empire Ladies Reform Association - who were they?

保皇女会成员 - 温哥华/二埠分会

Who belonged to the Association? About half of the Vancouver members seem to have been ladies related to the wealthy merchant Yip Sang (Pinyin: Ye Sen or Ye Chuntian 葉生 or 葉春田, also called by the name of his store, Wing Sang 永生. On the above photo montage, those identified thus far are:

Hence, it seems possible that the Victoria and Vancouver photos are of women's groups that existed more on paper than in reality. There is no evidence that the groups met frequently or for more than a year or two. And yet the photos are of great importance. They show that Chinese North Americans were already thinking about changes in the role of women. Further, because they depict real individuals [see below], they offer to historians a uniquely comprehensive view of elite Chinese women in two important cities where immigration restrictions were less severe than in the United States. The Canadian head tax did not restrict the immigration of wealthy Chinese women as greatly as did the American exclusion laws. Also -- as shown by the presence on one photo of three of Yip Sang's wives, all of whom lived in Vancouver at the same time -- Canadian immigration authorities were much more tolerant of polygamy than were their American counterparts.

The Victoria montage comes from Ray Lum, courtesy of the of the Harvard-Yenching Library at Harvard University. The Vancouver montage was rephotographed by the editors at the Vancouver City Archives.

Note 1: San Francisco Chronicle 1902-11-03

Note 2: See Judy Yung, Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco. Berkeley: U.of California Press,

2005.

Note 3: See http://www.britishcolonist.ca/; search for "Empire Reform," etc.

Note 4: The town was Rossland, a mining center in southeastern British Columbia. with a small and poor Chinese population

that is shown in a Baohuanghui photo as being large and prosperous, with all the men having pigtails and each taking

turns to wear the same Western suit. See the Associations page of this website.

Note 5: Seattle Times 1905-02-13

We do not know that the BHH was deliberately being untruthful about the number and character of its members. But the organization could have had several reasons for doing so: to seem larger and richer than it really was; to look more progressive than it actually could be in view of persisting traditional attitudes in Canadian and American Chinatowns; and/or to entourage social changes in China by exaggerating the speed of similar changes among Chinese on the American side of the Pacific.

0A. Ye Meirong 葉美蓉 [Yip May Young]. Leader. A 16-year old daughter of

Charley Yip Yen 叶恩, President of the national Baohuanghui of Canada.

0E. Kang Tongbi [Kang Tung Pih] 康同壁. Leader. Daughter of Kang Youwei

康有为, president of the Chinese Empire Reform Association. Kang Tongbi also

appears directly under the emperor's image on the Victoria photo.

1C. Li Jihuan 李姬欢, Vice President. The 1st wife of Charley Yip Yen, aka Huibo

惠伯, who was a nephew of Yip Sang.

1E. Nellie Yip Quong, English Secretary. Wife of Ye [Yip] Quong, a son of Yip Sang.

A Bostonian English teacher who married Yip Quong in New York in 1900 and moved to

Vancouver in 1904 to be with his family, Nellie was very new to Vancouver's Chinatown

community when recruited by the Association there. She spoke good Chinese.

2B. Li Caiyue 李彩月, Board Member. Wife of Ye [Yip] Tingsan, aka Yip On,

葉庭三, a nephew of Yip Sang and brother of Charlie Yip Yen.

2C. Zhang Jinman 张金满 , Board Member. The 2nd wife of Charley Yip Yen.

2D. Huang Hongyun 黄红雲, Board Member. The 3rd wife of Yip Sang.

2E. Deng Yunkai 鄧雲開, Chinese Secretary. The 2nd wife of Yip Sang.

3E. Chen Qing 陈青, Board Member. The 4th wife of Yip Sang.

4B. Li Lianzhu 李連珠, Board Member. The wife of Ye Qiu Yao [Yip Kew Yow]

葉求耀, the 1st son of Yip Sang.

4E. Ye Jinwei [Yip Gum Mei] 葉金薇 , Board Member. The 2nd daughter of Yip

Sang and Huang Hongyun (3rd wife). In 1904 Jinwei was only 11 years old.

Jane Leung Larson, the leading American authority on the Baohuanghui, has just (2011-03-10) informed us that Kang Tongbi, the daughter of Kang Youwei and designated leader of the Ladies' Baohuanghui (she appears near the top of both of these pictures), did organize a "New-York Ladies' branch of the Chinese Reform Association" with "All the prominent women of Chinatown enrolling themselves as members," according to the New York Daily Tribune, 1903-11-01. This makes it seem more likely that the Victoria and Vancouver branches did actually exist.

In 1900 Chinese Women in BC Had Already Begun to Organize --

for Charity 1900年卑斯省教会妇女关心社会

A member of the Chinese Methodist Church, the wife of that church's pastor in Vancouver and New Westminster, and then in Victoria, Mrs. Chan Sing Kai, or Chow Kate Shee, was in an exceptional position to begin organizing women for charity. She started in 1900, three years before Kang Tongbi arrived in Victoria and became president of the newly formed Chinese Empire Ladies Reform Association.

Kang Tongbi in the Pacific Northwest -- A Bright Teenager Leads CELRA, the Ladies' Baohuanghui 保皇女会领袖 - 康同壁在西北角的活动

The ladies' branches of the Chinese Empire Reform Associations in Vancouver and Victoria accepted Kang Tongbi, the daughter of Kang Youwei, as their leader. As shown in the two photo montages above, she is seen in, surprisingly, an old-fashioned cloud-pattern cape befitting an upper class woman of the imperial era rather than a pioneering advocate of women's rights. Much of Tongbi's life history can be gotten from books and websites. Here we will just include a few events relevent to the history of the Northwest.

The Guangxu emperor's image appears in the top center position on both montages. It was he whom the Baohuanghui (literally, the "Protect-the-Emperor Association") proposed to defend against anti-reform forces led by Cixi, the Empress Dowager. The two other men on the upper part of the Victoria montage are Kang Youwei 康有为, president of the Association (and father of Kang Tongbi), and Liang Qichao 梁启超, vice president.

References:

His Dominion and the Yellow Peril, Protestant Missions to the Chinese Immigrants in Canada, 1859-1967, p.51.

British Colonist, October 9; November 14, 1900.

The right-hand photo is from the Chinese Exclusion files at NARA, Seattle

Five other donors were wives of men who were prominent later in the Vancouver CERA:

- Mrs. Ling Dang. Wife of Ruan [Goon] Lindeng. Vice President of the CERA, #2D on the men's CERA montage.

- Mrs. Charlie Yip Yun. Wife of the president of the CERA of Canada, #2E on the men's montage.

- Mrs. Ho Chans, maiden name Ling Foy. Wife of He Can, a board member of the CERA, #5H on the men's montage.

- Mrs. Seid Sing Gaw. Wife of Xue Singjiao, a board member of the CERA, #2A on the men's montage.

- Mrs. Won Alexander Cumyow, maiden name Yea [Eva] Chan, wife of the official interpreter of the CERA, #1J on the

Significantly, there was overlap between Mrs. Chan's donors and those who, three years later, joined the Chinese Empire Ladies Reform Association. It is hard not to conclude that her efforts helped prepare local women for taking a less passive stance within the community. Was this due to the influence of Christians, including Mrs. Chan and her husband? Quite possibly. By the beginning of the 20th century, women's rights had become part of the teaching of many Protestant missionaries within China and among overseas Chinese.

However, we should not discount the influence of progressive Chinese thinkers like the statesman Duan Fang 端方 and the entrepreneur Zheng Guanying 郑观应. The Canadian and American English-language media must have played a role too. It would have been hard for a Chinese wife in Vancouver or San Francisco not to notice that upper-class white women appeared freely in public places, conversed with men as equals, belonged to prestigious ladies' clubs, and contributed publicly to ladies' charities. Old-fashioned Chinese husbands may have tried to convince their wives that such white women were only expensive courtesans and not at all respectable. Yet some of those wives would surely have been aware that the "courtesans" in question included the Governor-general's wife, the President's daughters, and the Queen of England.

She evidently was present in person for the founding of the first, Victoria, branch of CELRA in 1903 (see above) but probably not for the founding of the Vancouver branch a year later. In May 1903, Tongbi gave a number of public speeches on China reform subjects that were much admired by the local Chinese audience, according to the British Colonist. She toured around the area a little, went to Vancouver, Seattle, and Portland, stopped in Chicago for three weeks, and then proceeded to Hartford, Conecticut, to study before entering Barnard College at Columbia University in New York City..

In 1910 Tongbi was still in America. She gave a speech about her life in America and her career plans in China after she returned. She talked positively about the importance of voting and property rights for Chinese women, proposing to organize a women's club for educational purposes. In that speech she made no reference to the various branches of CELRA of which she had been the nominal head. Presumably those branches had died by then, perhaps because her father Kang Youwei and his reformist Baohuanghui movement had lost favor with the Chinese public in its rivalry with Sun Yat-sen's more revolutionary Tongmenghui 同盟会.

Chinese-American women did not necessarily benefit when the revolution-aries replaced the reformists. Kang Youwei showed a greater interest in women's rights than did Sun Yat-Sen.

References:

British Colonist, May 23, 1903. "A Reformer's Daughter".

Chicago Tribune, March 20, 1910. "My Experiences in America in Studying for Reform Work".

#3E. Chen Qing in later years .Photo:Vancouver City Museum

Among Mrs. Chan's donors was Miss Yip May Young 叶美蓉, who became one of the two leaders of the Ladies chapter of the Chinese Empire Reform Association (#0A on the women's picture above). She was 16 in 1904, when both of these pictures were taken. Right: NARA, Seattle.

Another BHH specialist, Zhongping Chen of the University of Victoria, points out (2011-03-13) that Kang Tongbi, daughter of Kang Youwei and first president of the Ladies' BHH, was indeed in Victoria in 1903 and that she was credited by one English-language newspaper with founding the ladies' organization. Chen quotes the newspaper as saying: "The Chinese women resident in this city last night formed a women's branch of the association, elected officers and went through regular organization business...Miss Kang, daughter of Kang You wei, a reformer, presided at the meeting and directed the organization work." (May 29, 1903)

#1E. Nellie Yip Quong

References:

Hoover Institution, Survey of Race Relations, 24-11.

National Archives & Records Administration, Seattle. Files Sumas 3-61, RS2391, RS2399.

Yip Family Tree, Burton Library, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Yip Sang, incidentally, had an unusually large number of children, daughters as well as at least 18 sons. However, in 1904 most of Yip's own daughters were too young to belong, and his sons were much too young to have fathered granddaughters. This may explain why so many wives and daughters of nephews were included along with Yip's eldest daughter, Jinwei or Gum Mei (4E above). That an 11 year-old girl had to be shown as a full member could mean that the Vancouver branch of the Ladies' Baohuanghui was not overwhelmed with applications for membership.

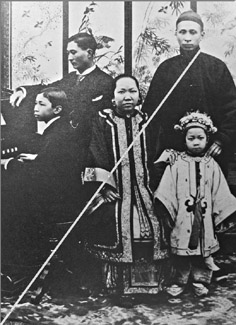

Yip Gum Mei (4E) with father, Yip Sang, and three brothers in 1909. She was 16 when this photo was taken. Photo from NARA Chinese Exckusion Files,

Li Caiyu (2B)i with husband, Yip On, and son in 1909. Photo from NARA Chinese Exckusion Files,

Among the nephews of Yip Sang was Yip On 叶敦, Secretary of the (men's) Baohuanghui in Vancouver and a successful businessman in his own right. We do not know how the name of his wife, Li Caiyue, was pronounced by Vancouver Chinese. In this picture, taken in 1909, she appears to be heavier than in the above Ladies' Baohuanghui montage.

Lives of Chinese Women in the Pacific Northwest 早期挨达荷州的华人妇女

A few must have arrived in the 1860s, and there were a good many by the 1880s, although Chinese men still greatly outnumbered Chinese women. Often the women were prostitutes. Just as, or even more, often they were respectable married women. And a growing number were American-born, which meant not only that they had a citizen's legal rights but also attitudes that might be quite different from those of their mothers. Several outstanding Northwestern Chinese women--Chow Kate Shee, Kang Tongbi, and Yip May Young-- have already been mentioned. This section offers brief sketches of others. All lived in the Pacific Northwest between the 1870s and the 1920s.

Idaho Women, photos from 1890-1920. Credit: NARA in Seattle & Idaho Statesman.

Soo Po Lin, b.1878

1911 Applied for re-entry permit before trip to

1909 Stayed in Salt Lake City (Utah), Boise,

1908 Separated. Moved to Portland, Oregon.

1903 Married Charley Wong in White Eagle,

1902 Lived in Sacramento

1898 Landed in San Francisco

Illiterate and a prostitute by profession, Soo Po Lin appears here as a self-possessed woman able to wear Western clothes with style and confidence. Soo Po Lin is one of the few Chinese prostitutes we have been able to

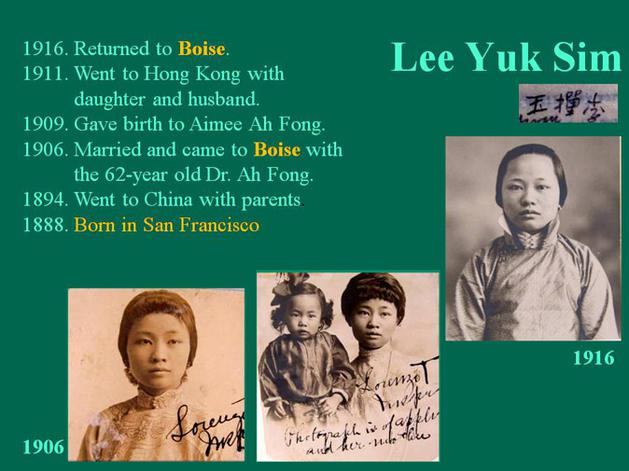

In spite of their difference in age, the marriage of Lee Yuk Sim and herbal doctor Ah Fong may have been a happy one. Yuk Sim was an intelligent, competent woman and her physician husband, well-to-do and respected in both the white and Chinese communities, is said to have been a kind man. Whether Yuk Sim was literate in any language is unclear, but she could at least write her name in Chinese and English.

Lee Yuk Sim, b.1888

1920 Now a mother of 4 girls and 2

sons, back in Boise.

1910-3 Became a mother, moved

to Seattle with family.

1909 Landed in the U.S and lived in

Boise.

1908 Married in China to 38 year-

old Fong Yow 邝耀 of Boise.

1891 Born in Siyap area, Guang-

dong Province, China

Lee Sap Ng, b.1891

Like most Chinese women in early Idaho (and unlike Lee Yuk Sim), Lee Sap Ng was China-born. The clumsiness of her signature shows that she could not write much Chinese but she came to Boise at a young enough age to have learned a fair amount of English. One should not read too much into her serious, slightly unhappy expression. Women were supposed to look that way in formal portraits -- the kind that usually included a central table with a clock, vase, teacup, and (often) a tobacco pipe.

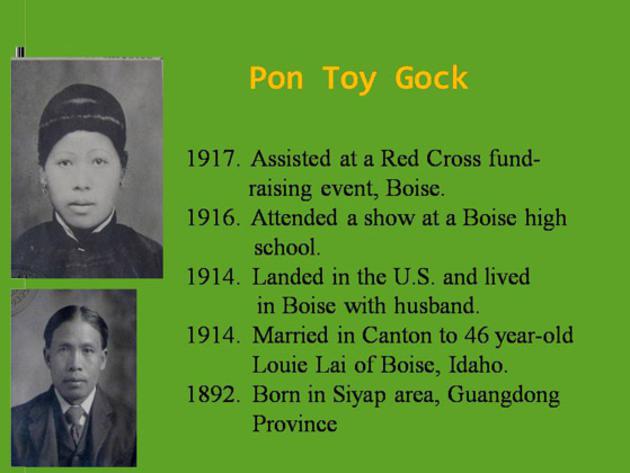

Pon Toy Gock, b.1892

That Toy Gock married at the advanced age of 22 may help to account for her cultural adaptability. The Red Cross event she attended was organized by European-American ladies in aid of American soldiers being sent to World War I battlefields. As the Red Cross was an upper-class charity in those days, we may presume that the organizers, and many of the participants too, belonged to Boise's elite. Toy Gock had only been in the U.S. for three years at that point. There is no sign that she knew any English when she arrived or that, as far as the Immigration Service knew, she had received any formal education back in China. And yet already she was capable of associating with ladies belonging to the white elite. It was an astonishing feat.

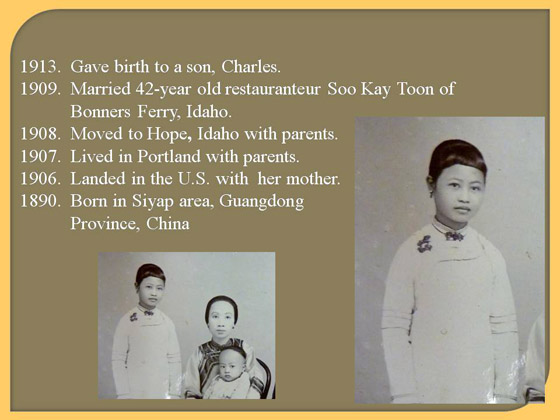

Moy Fong, b.1890

identify in premodern Idaho. We do not know whether she decided to return to China anyway, giving up the idea of reentering the U.S.

At least Moy Fong had parental support when she arrived in this country and had three years in which to learn about her new environment before being married off. And even after marrying, for several years she was still only forty miles from her parents. The average married female Chinese in Idaho was hundreds or thousands of miles from her nearest relative.

Cheng Moy Lan, b.1869

1912 Family returned to China

1908 Family moved to Hope,

Idaho.

1907 Had another daughter.

1906 Landed in Port Townsend

1888 Married 17-year old Moy

1869 Born in Guangdong, China

The immigration records do not.say why Moy Dot 梅达 decided to take the whole family (except Moy Fong, who was already married--see below) back to China. It could have been because his parents demanded it, because he and Moy Lan wished to give their children Chinese educations, or because he wanted to take another wife.

An important question: in the 19th and early 20th centuries, did Chinese women have more opportunities in North America than back in China? Did they think so? Did they make use of those opportunities? The answer depends on individual personality and experience, and on the nature of support systems.

In general, Chinese women were subject to the same gender prejudice, regardless of being in China or America. However, Chinese women in America at least had more options available. They could partially free themselves from the grip of ethnic tradition by choosing non-Chinese or progressive Chinese partners, or by seeking shelter and social outlets at Christian churches. Over time, Chinese men in America would change as well. They eventually came to respect their woman folks more as they assimilated Western values and models.

Equally important, in numerical as well as social terms, were non-Chinese women married to Chinese men. They too played a central role in early Chinese-American society. While the obstacles they faced were different, those were equally daunting (Click here for the Intermarriage page of this website).

Chinese women in early Idaho. For data and credits, click here.

| ||||

This page was last updated: August 30, 2018

ENTERTAINERS/PROSTITUTES 娼妓

Traditional Chinese were less offended by the existence of prostitution than white Northwesterners claimed to be. The profession was seen as a necessity and, even by civic leaders, as a business opportunity. The prostitutes themselves, who often had not entered the profession voluntarily, were pitied but also praised for the filial piety they showed in selling their bodies to support their parents. Were they themselves sold, as the white press regularly asserted? In a sense, but more as indentured workers than as slaves. It was always possible for a prostitute herself or a future husband to buy back her contract, and in that way for her to become a free and not particularly despised individual. Even in China, courtesans could become respectable second, third, or later wives of upper-class men. In North America, purchase money rather than social stigma was the main problem for a Chinese man wishing to marry a Chinese prostitute.

Incidentally, Chinese prostitutes never seem to have been too numerous in the Northwest. As was the case in most other parts of the U.S. and Canada, Chinese men in this region often consorted with European-American (and later, Japanese) prostitutes rather than their Chinese counterparts.

Annie Kum Chee had a hard life but seems to have been a tough and resilient person. She would probably have stayed in the U.S. if her original Presbyterian "rescuers" in San Francisco had not failed to register her as a resident Chinese as required by the Geary Act of 1892.

We are not clear why Chinese in Portland and Astoria wanted Ah Oy deported. If her personality matched her appearance, she was not an easy-going individual.

Because she has been the subject of many articles and several books, including the best-seller by Ruthanne Lum McCunn and a fine children's book by Priscilla Wegars, Polly is one of the best-known of all Chinese women in Northwestern history. Exceptionally self-reliant and adaptable, she was also unusual in that she married a white man in a period when East-West marriages in that direction were very rare. Due to the general scarcity of Chinese women in North America in those days, it was much more common for Chinese men to marry European women rather than the other way around.

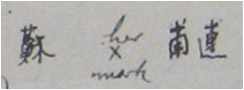

Polly Bemis's Chinese name is often given as Lalu Nathoy. This seems to us impossible. Only a handful of Chinese surnames have two syllables, and neither Lalu nor Nathoy is one of them. Moreover, neither the hard nor soft "th" sound occurs in any Chinese dialect. Besides, now we know her real Chinese name. It appears as her signature on a government registration document in Chinese Exclusion File #298172 at N.A.R.A./ Alaska-Pacific Region, Seattle. The two-character signature, as reproduced above, reads "Gong Heng," (恭亨) written inexpertly but legibly. For images of the relevant documents, click here and here. The documents show she claimed to be 47 in 1906, which would mean she was born in 1859.

Although Gong and Heng both can be family names, Gong was probably hers. Like several other Chinese who lived for long periods in the frontier West, she seems not to have been in contact with her family. Perhaps she had simply lost contact, though that would have been unusual in those days for either a prostitute or a respectably married Chinese woman who traveled overseas. Or perhaps she had cut off contact. Not all daughters sold into prostitution by hard-up parents can have reacted with filial devotion, sending money home faithfully year after year. Some must have been bitterly resentful. Polly Bemis/Gong Heng could represent one such case.

In the United States after the Exclusion Act of 1882, Chinese women were effectively barred from entering the country unless they were wives or daughters of a member of the exempt class: a merchant, a diplomat, a teacher or student at a pre-university or university level institution, or a "bona fide" (read: rich upper-class) tourist. A few female students (notably Kang Tongbi) did spend time here, but the majority of China-born Chinese women living legally in the Northwest were merchant's wives. Restrictions on Chinese female immigrants were less tight before 1882 in the U.S. and before the 1920s in Canada, but even then almost all women who were not prostitutes were the wives of merchants: that is, of store owners, industrialists, labor contractors and so forth.

Annie Kum Chee, b.1873

Polly Bemis (or Gong Heng -- 恭亨), b.1859

Ah Oy, birth year uncertain

AMERICAN-BORN CHINESE WOMEN

美籍商人妇

Being born in Canada did not make much difference:to Chinese women. The absence of birthright citizenship laws meant that no Chinese, male or female, could become a citizen or enjoy the same legal rights as white Canadians. This remained true until 1947.

The situation in the United States was different. As full citizens, America-born Chinese suffered few legal disabilities. Local real estate covenants banning sales to Chinese, being extra-legal, still applied, and Immigration still felt free to treat returning citizens of Chinese descent, especially women, with the same harshness as the China-born. But otherwise, female Chinese citizens were in a much stronger position than their sisters in Canada. For one thing, they not only could own property, including a deceased husband's property, but could expect their rights to be enforced by American courts. For another, as shown by the case of Dong Oy, they could use American bigamy laws to hinder or prevent their husbands from taking other wives. For a third, again as shown by Dong Oy, they could count on consular protection when in China or elsewhere abroad. And for a fourth, they could use the threat of American divorce law to improve their status in the household. Even the most self-centered of husbands must have found his chauvinistic instincts tamed by the prospect of paying American-style alimony, having half of everything he owned taken by a divorced wife (though only in community property states like Washington, Idaho, and California), and, worst of all, losing custody of his sons.

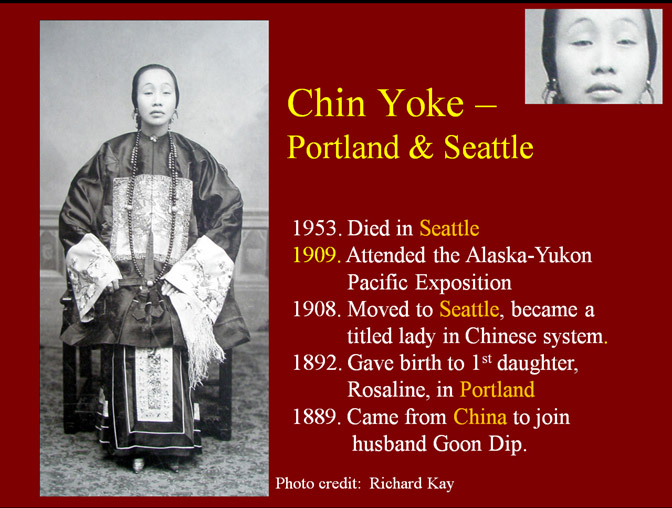

Chin Yoke, b.1870s

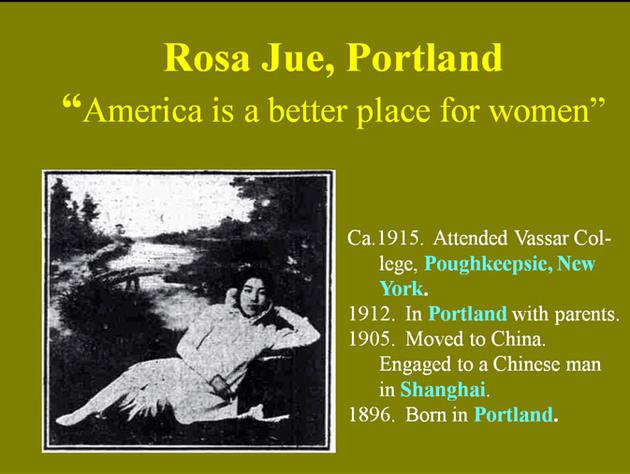

Rosa Jue, b.1896

Rosa, born of rich parents, had experienced more eventful teenaged years than most of her Vassar classmates. One gets the impression that she did not like China very much.

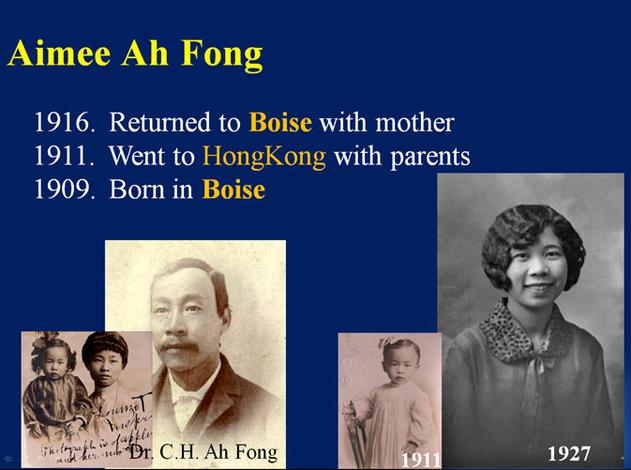

For some American-born Chinese girls, a childhood trip to China would have been an ominous sign. Such girls were often expected to stay there, perhaps to take care of a stepmother and/or to absorb the language and values that would make them, in traditional opinion, better wives. Sometimes an American-born girl in China would have a husband chosen for her and be obliged by her stepmother and paternal relatives to marry him. Luckily for Aimee, she had kind parents who were committed to life in America for their daughters as well as themselves.

Aimee Ah Fong, b.1909

With a rich, powerful, and long-lived husband, Chin Yoke became the highest-ranking Chinese woman in the American Northwest. Was she as haughty as she looked? We do not know but her grandchildren were fond of her. It may be significant that her husband, Goon Dip, though a brilliant businessman, was short, plump, unfashionably dressed, and not especially good looking.

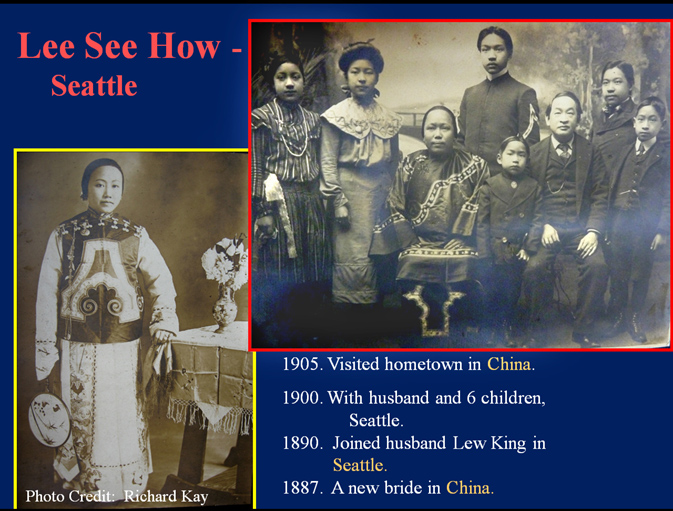

Lee See How, b. early 1870s

Later pictures of Lee See How show her as a somewhat heavy, genial woman. Her husband Lew King died in 1908. We do not know whether she inherited part of his estate, but her successful sons and daughters (one son became Goon Dip's right-hand man and another a noted boxer and doctor, while a daughter married the Canadian Pacific's main Chinese agent in Vancouver) ensured her a comfortable old age anyway. The last mention of her in the Seattle Times is in connection with her daughter's marriage in 1913.

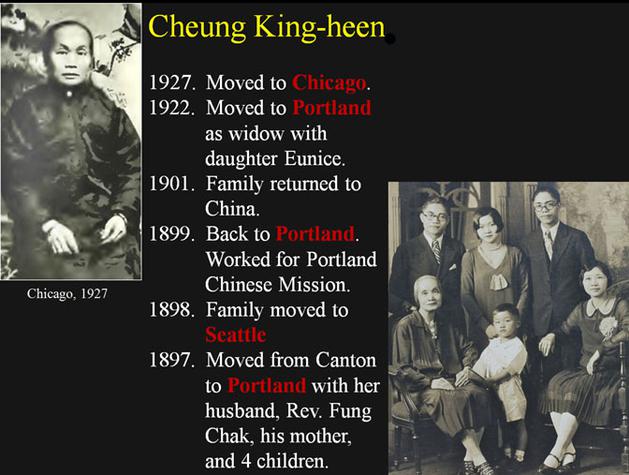

A talented and devout woman, Cheung King-heen shared in the missionary work of her husband both in China and the United States. Her English appears to have been good: she could proselytize in that language. One of her sons became a noted cartoonist, and a daughter married the son of the railroad and world fair entrepreneur Hong Sling, at the time a resident of Hong Kong.

Cheung King-heen, b. 1870s?

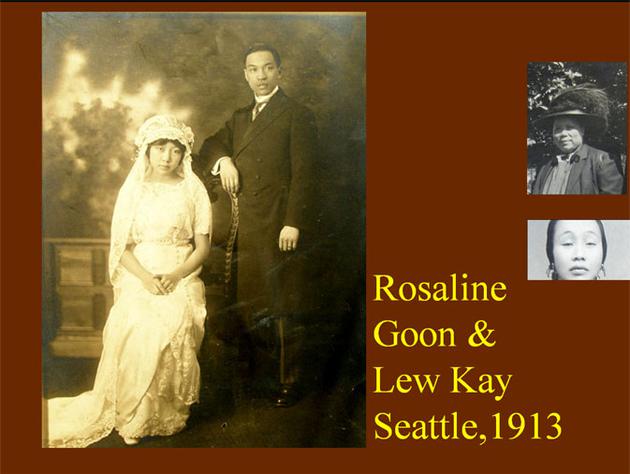

Rosaline Goon, b. early 1890s

Rosaline was the daughter of Goon Dip and her husband was the son of Lew King. Both fathers were among the wealthiest Chinese in the Pacific Northwest. Rosaline's and Lew's mothers were Chin Yoke and Lee See How, whose thumbnail biographies appear on this page and whose pictures are shown to the right of the wedding photo. That both lived in the Seattle area (and were rich) must have been helpful to the newlyweds. Rosaline neither attended college nor played a conspicuous role in Seattle's Chinese community

Thus far we have found no evidence that Seattle ever had a branch of CELRA, the Ladies' Baohuanghui. In 1905, Kang Youwei visited that city en route to Portland from British Columbia. In the morning after his arrival he, "accompanied by the principal Chinese merchants of the city and the members of the Portland delegation drove about the city. In the afternoon at The Butler there was a reception which was attended by about thirty Chinese women and all the principal Chinamen in the city" (Note 5). Getting so many respectable Chinese women together from Seattle's rather small Chinese community was a promising start, but nothing seems to have come of it. Perhaps by 1905 enthusiasm for CELRA had already begun to wane in spite of Kang's evident interest in getting women involved with his reform movement.

In essence, Mrs. Chan was replicating within the Chinese community what white women were already doing among European-Americans -- using fund-raising for charitable causes to promote women's roles in society as a whole. Like many contemporary white female Christians, Mrs. Chan focused her efforts on raising funds for famine and disaster relief. On two occasions, she collected money not for China but for India. In October, 1900, for instance, when she and her husband were based in Victoria, she collected $64 from "the Chinese women and children of Victoria" for Indian famine relief. More than half of the 61 donors were women. A month later she was in Vancouver fund-raising for the same cause. This time she collected $46.50 from the Chinese women and children of Vancouver and New Westminster. 39 of the 56 donors were women.

Rev. Chan & family. Mrs. Chan Singkai (née Chow Kate Shee) is in the middle. Standing on the left is Alexander Won Cumyow who would later marry Eva Chan, lower right. The photo may now belong to the University of British Columbia. We are currently clarifying the issue of reproduction rights

The Youthful Leadership of the Ladies' Baohuanghui, All Dressed Up

The official leaders of the organization. looking very serious, may not have enjoyed dressing up even though, after all, they still were girls. This picture, published in the exhibition catalogue, Gum Shan, in Vancouver, Yip, seems to have been taken so that the pictures could be used in the photo-montage of the Vancouver-New Westminster CELRA (see above), probably in 1904. In that year, Yip May Young was 16. Kang Tongbi was 19.

Yip Mei Young 叶美蓉 is on the left, Kang Tongbi 康同壁 in the center, and Yip Gum Mei 葉金薇on the right. The two Yips wear jackets and trousers in the traditional southern Chinese style. Kang wears a one-piece northern Chinese qipao with a formal cloud collar. It is not clear why all three wore traditional outfits in a publicity photo for an organization dedicated to creating a new, modern, and pro-feminist China. Perhaps they did want to look all that revolutionary.

pushover. She may well have felt that she had had it with men.

Maggie herself was interested in cultural integration and not opposed to the idea of marriage. In 1915 she appeared in the Junior Drama League's Shakespeare pageant as a dancer in Midsummer Night's Dream [Note 7]. Later she married architect Sam Chin, the designer of the Chong Wa Benevolent Association building in Seattle's Chinatown [Note 8]. The marriage is said to have been a happy one, although the couple had no children.

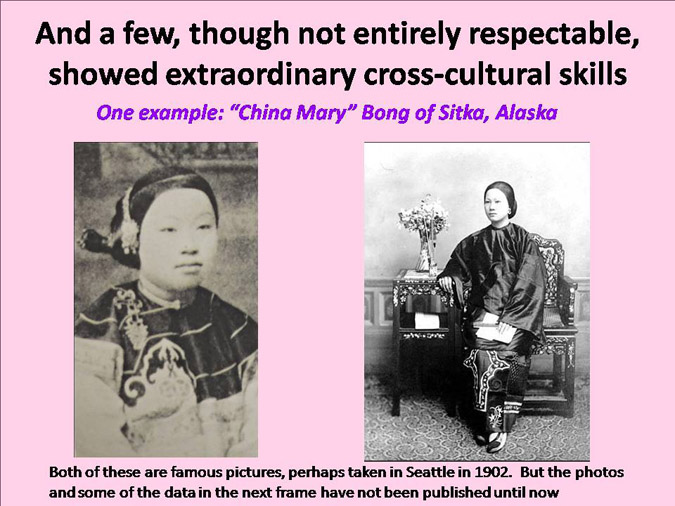

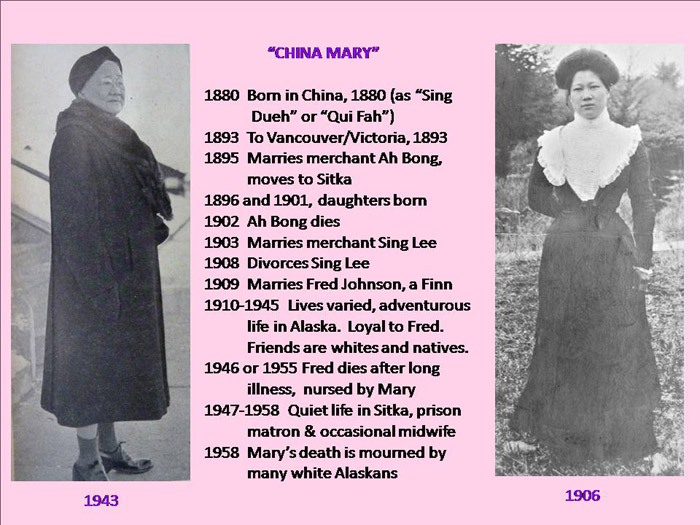

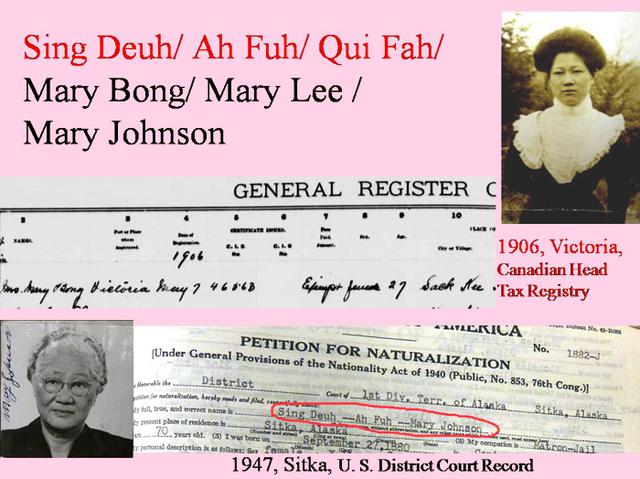

Mary Bong or "China Mary," 1880-1958

Born in China as Sing Deuh, Ah Fuh/Fur, or Qui Fah and called China Mary by Alaskans, Mary Bong had an adventurous life that she seems to have spiced up in the interviews on which several popular articles and a PBS television segment were based. The data presented here have been checked against records in the Alaska State Archives and an excellent critical article by Robert A. DeArmond that appeared in the Sitka Sentinel in April and May 1987, kindly showed to us by staff at the Sitka city library. DeArmond's contention that she was married three (not, as she claimed two) times and that she divorced her second husband, Sing Lee, is supported by State Archives data. DeArmond was delicately unskeptical about Mary's claim, accepted by PBS, that she ran away from home in China at the age of 9 and that by hard work she had saved enough money to pay for passage to Victoria at the age of 13. Now, perhaps, such delicacy is not needed. The Canadian Head Tax Registry compiled by the University of British Columbia did not record Mary's earlier names. She must have come to Canada as a servant girl who soon was forced to become a prostitute, if that had not happened already. Her subsequent success seems to have been due to her good looks, intelligence, and exceptional adaptability.

Mary seems to have spoken excellent English. When she went from Seattle to Victoria in 1906 to see her dying daughter, Katherine, she did not need an interpreter at the Immigration station. Her file at the National Archives and Records Administration division in Seattle shows that she was a native of Shiqi (Shek Kee 石岐) in Zhongshan 中山 county. Like Polly Bemis in Idaho, Mary took to the frontier life, living contentedly with her third husband Fred Johnson (a Finnish immigrant who may not have become a U.S. citizen) until his death. Unlike Polly, Mary was firmly in control of her own life. She was the one who sued for divorce from her second husband Sing Lee in order to marry Fred, his business associate. As Sing Lee was rich and Fred was not, she may have remarried for love instead of money.

Reference and acknowledgement:

- NARA, Seattle File RS1147; UBC-Headtax Registry Project; Sitka Public Library, Alaska State Library, Historical Collections (Sandra Johnson); Alaska State Archives (Tatyana Stepanova & Abby Focht).

- University of Washington, special Collection - Society and Culture Collection, Soco261 Mary Bong

- http://www.sitkahistory.org/dar-ladies.shtml

CHINA-BORN MERCHANTS' WIVES 华籍商人妇

| ||||

(UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED ALL DATA ON THIS PAGE COMES FROM THE EDITORS' OWN RESEARCH ON PRIMARY SOURCES & ARTIFACTS)

Added note (11/22/12). Ruthanne Lum McCunn has just sent us a copy of the revised 2004 edition of her Thousand Pieces of Gold, with the gentle suggestion that we might want to look at the additional research on Polly's names included in that edition. She is right. We are embarrassed to have implied we were the discoverers of Polly's Chinese name, Gong Heng. We should have known. By 2004, several capable Chinese American scholars, including Marlon Hom and Judy Yung, had already seen Polly's registration certificate and read her Chinese name as "Gung Heung," and the revised edition of TPOG had already published that fact.

The revised edition also includes a theory suggested to Ms. McCunn by Huang Youfu (黃有福), now at Beijing's Minzu (Nationalities) University, that the name "Lalu Nathoy" could indicate that Polly was born as a member of the Manchu/Mongolian-speaking Daur minority of far northeastern China.

While Professor Huang's suggestion may make linguistic sense, it does entail some practical difficulties. Although a few Chinese women did reach North America from Beijing and Shanghai in the 19th century (several appear in the Canadian Head Tax records), it would not have been cheap or easy to bring a "slave girl" from the distant Mongolian-Manchurian steppes more than fifteen hundred kilometers to Hong Kong, in 1870 the departure point for almost all servant girls/ prostitutes sent to North America. Why would the buyer of an ordinary untrained tribal girl have gone to such expense? How could she have had bound feet, when that practice was strictly forbidden by the Imperial government for all Manchu-connected females? How could she have communicated, even if she spoke some Mandarin along with her tribal language, in a Northwest American Chinese world where almost no one spoke anything except pidgin English, dialects of Cantonese, and the Chinook Jargon?

So we think that the northern tribal hypothesis, while interesting, should be received with caution. We find it easier to believe that Polly's birthplace, described by her biographers as being "near one of the upper rivers of China," was on the hilly northern border of Guangdong or Guangxi province, that when young she spoke a form of Cantonese, perhaps together with a tribal language, and that her girlhood home was at most only a few hundred kilometers from Hong Kong, whence she was sent to America. As for the Lalu Nathoy name, "Lalu" could be an invention by a local white acquaintance--it is not attested by any source until after Polly's death (by Sister Alfreda Elsensohn, Idaho Chinese Lore, 1979: p 80-1). "Nathoy" appears on her marriage certificate where the first letter is either a N or an H. In either case, it could be a corruption of "Ah Toy," a common Cantonese/ Taishanese woman's name.

Polly Bemis seems to have been an extraordinary individual, and one whose life has been described by an exceptional group of writer-historians. Her fame has caused most public and private records to be thoroughly searched. However, one remains hopeful. New documents may yet appear that will solve the Polly problem once and for all.

UW-Special Collection

Photo:

E.W. Merrill

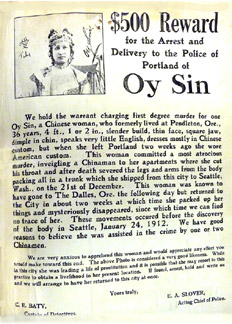

The Beautiful, Notorious Oi Sen 爱仙 – 辣手娇娃 [Note 1a]

To newspapermen, the central figure of the sensational Seid Bing 薛炳 murder case of 1912 was not the deceased but one of his accused murderers, the beautiful Oi Sen or Oy Sin (also pronounced Choy Sing) 彩胜, originally named Bai Mei Fung 白美凤, and formerly married to one Ung Goey of Pendleton, Oregon [Note 1b].

At the time reported as 19 but later shown to be either 33 or 36, Oi Sen was a noted beauty and, depending on who was speaking, either a prostitute or a courtesan. White newspapers persisted in calling her a “slave,” but in this case the term was simply a euphemism for a Chinese lady of ill repute. Oi Sen seems to have been independent and successful in her trade. She claimed to have been born in the United States.

Seid Bing, the papers said, had been obsessed with her. His family name and membership in the Bow Leong Tong 保良堂 had marked him for death at the hands of the Hop Sing Tong 合胜堂, of which she had long been a member. The killing put her squarely between the Hop Sing and the Bow Leong. Now she posed a danger to both. So she reacted like any intelligent person. She fled for her life, setting in motion a multi-state manhunt. The Seid family and the Hop Sing, through the Portland police, immediately offered a $500 reward.

They caught her within a few days, in Montana where she had once lived and had friends. With her she had a $150 pawn ticket for Seid Back’s diamond ring and a baggage claim check for the trunk with Seid Bing’s body. Why she kept the claim check is not clear. The subsequent trial would show that she was far from stupid.

Portland’s Chief of Police and Seid Back, Jr. 薛天眷, son of the wealthy Seid Back 薛栢 and cousin of the deceased, went by train to Montana to bring Oi Sen back. She waived extradition. Upon arrival in Portland, she began to tell her side of the story: that the real murderers were two Hop Sing Tong members, Wong Si Sam 黄世森 and Law Soon 罗旋. They were the ones, she said, who did the killing and butchering while she hid in another room. Considering that she was a small woman weighing only 99 pounds while her supposed victim was a tall, moderately heavy man—the trunk with him in it weighed 175 pounds—no one believed that she had acted alone. Afterward, Wong and Law forced her to hire a deliveryman to take the trunk to the Portland railroad station and to sign the shipping papers herself [Note 2].

Oi Sen and her reward poster, January, 1912. According to the poster, she was 4 feet 1-2 inches tall. This was probably not true. The median height of several hundred southern Chinese women who immigrated to Canada between 1890 and 1940, as listed in the University of British Columbia's compilation of Head Tax records, was 5'1" to 5'2". None of the sources describe Oi Sen as being abnormally short. Hence, her height was probably close to the median: an inch or two over 5 feet. She weighed 99 pounds and at the time of the trial was in her middle 30s.

The editors owe thanks to Liisa Penner of the Clatsop County Historical Society, who told us the poster existed, and to Anne Odom of the Astoria Public Library, who found it for us.

Part of the reason may have been the good impression she created in court. She had already told the press that “she had the picture of the murdered Seid Bing in her heart and could not forget him” [Note 3]. Now her testimony was intelligent, unhesitating and even humorous. She said that Seid Bing had been her “sweetheart.” On the afternoon before the murder, she had overheard Law Soon and other Hop Sing men, whom she refused to name, discussing a plan to kill her and Seid Bing. She had warned Seid but he just laughed, saying he was not afraid. After the murder, she claimed, she had kept quiet out of fear, having been repeatedly threatened with death unless she complied with the killers’ orders. [Note 4].

So she got off scot-free. Was she a willing accomplice to the murder, luring Seid to a place where he could be easily killed? Possibly. According to her own testimony she knew what was planned, and must have suspected that her role was to get Seid Bing alone, away from fellow Bow Leongs and possible bodyguards. Was she in a position to refuse? Would that have meant her being murdered as well? Perhaps—as a woman, the oaths sworn by Hop Sings to support their fellows would not have protected her. On the other hand, she was a prime asset and knew it. Despite her damning testimony against their members, she seems to have been immune to Hop Sing and Bow Leong vengeance. She could have known in advance that no one would dare touch her if she refused to go along with the murder plot.

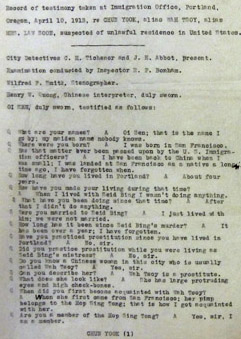

But could she have deliberately set her lover up for the Hop Sing’s hit men? Again, possibly. She had a ruthless side, as shown by her uncompromisingly harsh description of her fellow prostitute and Hop Sing member, Wah Tsoy (also Chun Yook), when the latter was threatened with deportation. In a long interview at the Immigration Office in Portland, she was unwaveringly critical of Wah Tsoy, her morals, and her supposed marriage to Law Soon, the Hop Sing capo who had murdered Seid Bing in her, Oi Sen’s, presence [Note 5].

On the other hand, her testimony, though unsparing, also showed character and great courage. While Wah Tsoy was not a threat to anyone, Law Soon was both a fellow Hop Sing member and a hardened killer to whom her testimony looked like rank betrayal. As he had said in 1912, “Oi Sen is putting up a job on me, and I don’t like it. If I did that, I ought to be punished. I told Oi Sen to look to heaven for her reward” [Note 6].

One of her defenses was to say, often and publicly, that the Hip Sing would attempt to murder her. Another was to seek protection by non-Chinese agencies. As late as February, 1913, she was still refusing to leave the convent of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd, where she had been secretly placed by

county officers for protection as a key witness [Note 7]. A third was to stay as close as possible to the clan and secret society of her former lover and supposed victim, Seid Bing. The Seids and the Bow Leong Tong had already been enemies of the Hop Sing for many years [Note 8]. That Law Soon, one of Seid Bing’s killers, was threatening her may have convinced the Seids that she deserved protection.

The problem for her was to get a commitment from them. Her solution, adding yet another twist to a tangled tale, was to marry into the clan. On June 25, 1914, she joined Seid Wing, merchant, former Bow Leong highbinder, police informant, and clan cousin of Seid Back, Jr., in an American-style civil wedding ceremony [Note 9]. Judge Stevenson performed the marriage. She wore blue Chinese silk for the ceremony and carried a bouquet of sweet peas, the gift of her lawyer. The deputy clerk of the municipal court and an assistant in the Department of Public Safety for Women served as official witnesses, and the room was crowded with police attaches. She used her real name, May Fong. Seid Wing gave his age as 36 years. The bride just afirmed that she was of legal age [Note 10].

As far as we, the editors, know, the newlyweds lived happily ever after. There is no record of revenge by highbinders of the Hop Sing or any other secret society .

Transcript of Oi Sen's testimony at the Immigration Bureau's deportation hearing on Chun Yook, a suspected prostitute, in 1913. Click here for more,

Note 1a. Names in Chinese have been taken from articles on the Seid Bing murder in January and February 1912 issues of San Francisco's Chinese-language newspaper, Chung Sai Yat Pao 中西日報

Note 1 East Oregonian (Pendleton) 1913-02-15

Note 2 See Oregonian citations for the Seid Bing article on this website’s Secret Societies page

Note 3. Oregonian 1912-02-03

Note 4. Oregonian 1912-04-18

Note 5. NARA-Seattle, Chinese Exclusion Files, #4441 (Chun Yook)

Note 6. Oregonian 1912-02-04

Note 7. Oregonian 1912-12-18; East Oregonian (Pendleton) 1913-02-15

Note 8. Hawaiian Gazette 1889-01-08

Note 9. For Seid Wing’s police connections, see Oregonian 1913-03-19

Note 10 Oregonian 1914-06-26.