TEMPLES & SHRINES - 2 庙宇莊厳. 殿堂清静

金山西北角 - 华裔研究中心

This page was last updated: August 30, 2018

(UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED ALL DATA ON THIS PAGE COMES FROM THE EDITORS' OWN RESEARCH ON PRIMARY SOURCES & ARTIFACTS)

Bei Di 北帝, God of the North. In the U.S. and Canada, he was known by at least two names: the North God (Bei Di in Mandarin and Bok Dai, Pak Tei, Pak Tie, Bok Kai, Buck Eye, and Beuk Aie in Cantonese and/or Taishanese), and, more formally, as the Lord of the Dark Heavens (玄天上帝 Xuantian Shangdi). Modern martial artists revere him too. They call him "Dark Warrior" (玄武 Xuan Wu) or "True Warrior" (真武 Zhen Wu). He is believed to preside over the North, the color of which is black. Unlike Guan Di and Tian Hou who are deified mortals, Bei Di has always been a celestial being, embodying the Great Dipper constellation.

One of his most famous temples, surely known by repute to all early Chinese immigrants in California, is the Ancestor Temple in Foshan near Guangzhou, which commemorates his miraculous driving off of a hostile army in the 15th century. He also has the power to contriol fire, to summon rain, and to regulate water flow, henc is seen as a preventer of floods and fire. He is shown in either military or official clothes, usually bald or with a bald forhead, armed with his seven-star sword, and often with a tortoise and snake under or next to his shoeless feet. Fresno Historical Society. 1880s? Photo by Ruth Lang, Fresno Historical Society.

Cai Shen 财神, God of Wealth, is a popular but relatively minor deity. His name is invoked during Chinese New Year celebrations. In statues and pictures, he appears in the dress of a court official, sometimes with a gold ingot in his hand. Won Lim Temple, 云林庙 Weaverville, California, 1870s-80s.

Guan Di 关帝, God of War and Brotherhood. A historical figure of the 3rd century AD, Guan 关羽 over the years became a symbol for military skill and unshakeable integrity as the hero of dramas and early novels like the extraordinarily popular Romance of the Three Kingdoms 三国演义. Within a few centuries of his death he began to be seen as a god. He received grand titles like Guan Gong (Duke of Guan), Guan Di (sometimes spelled Kwan-ti), and Wu Di 武帝 (Warrior Emperor). Because of his courage and loyalty to his comrades, he continues to be revered by soldiers, police, criminals, and fraternal societies of all sorts. He is almost always depicted with a red face, slanting eyes of the kind known as phoenix eyes, and a beard made of five long strands, wearing either armor or civilian official clothes, and holding his favorite weapon, an enormous axe-like halberd. Hongmen Dart Coon Club Shrine 洪门达权社 , Vancouver, British Columba, 1890s-1900s.

Guan Yin 观音or Kun Yum (in Cantonese) and Kannon (in Japanese), the Goddess of Mercy. Often the only Buddhist on a Daoist altar, she is the Chinese version of the Indian Buddhist deity Avalokitesvara. She is a bodhisattva, one who has achieved enlightenment but refused to enter Nirvana (and become a true Buddha) out of compassion for suffering beings. While no bodhisattva has gender, Chinese usually think of her as being female: especially concerned for women and children, immensely powerful, benevolent, loving, and venerated by just about everyone—Buddhists, Daoists, and even agnostics. She can be recognized by her costume, which in male Indian style exposes the upper part of her chest and her headdress which often includes a small Buddha. Statues or pictures of her are usually present not only in Buddhist but also in Daoist temples, in positions of varying importance. This and a statue in Weaverville's Won Lim Temple are probably the only surviving images of her owned by American Chinese before 1900. Kong Chow Association Shrine 冈州会馆, Los Angeles, California, 1880s-1890s.

Hua Tuo 华陀, God of Medicine. A former mortal, Hua Tuo is said to have cured Guan Di from a poison arrow wound and later to have been executed by Guan Di’s merciless enemy, Cao Cao 曹操. His ideas of surgery, acupuncture, and tai chi movements had an important influence on later Chinese medicine and led to his coming to be seen as a god within a few centuries of his death. He is sometimes shown holding a bottle or gourd containing herbal medicine. Early images of Hua Tuo appear in the Marysville and Weaverville temples. Bok Kai Temple 北溪庙, Marysville, California, 1880s.

Jin Hua 金花 (华) 娘娘 or Lady Golden Flower. A southern Chinese virgin deity already popular in 17th century Guangzhou, Jin Hua is especially popular among women. She helps with women’s and young children’s health: with pregnancy, delivery, and pediatric problems, a cult connected with Bixia Yuanjin 碧霞元君, the Lady of the Azure Cloud, an important goddess in northern Chins. One of Jin Hua's traditional symbols is an elaborate phoenix head-gear. However, that is not obvious here, where she is draped with a red ribbon. Bok Kai Temple, 北溪庙Marysville, California, 1880s.

Suijing Bo 绥 靖 伯 (the Pacifying Duke) is less famous nowadays, although noted in his earthly life (the 13th century) as a fighter against bandits and after deification as a protector against epidemics. The latter role contributed to the spread of reverence for him during the 19th century, from a few temples in Guangdong to many towns in southern China and Southeast Asia. The authors know of five temples in North America that once featured him as a chief deity, including the temple complex at Oroville. Because his mortal surname was Chen, most Chen (Chin/Chinn/ Chan) clan associations place his image or name on the altars of their shrines. Chens in Oroville built a separate structure for his shrine. This image in that shrine is the finest in North America. Chan Shrine 陈 绥 靖 伯庙 , Chinese Temple Museum, Oroville, California, 19th century.

Tam Gong (Tam Kung) 谭公 is a Daoist deity, popular in the South China around Hong Kong and Macau but also worshiped in Malaysia, British Columbia, and formerly inSan Francisco. He was a real human being—a member of the Hakka speech group—who lived in Kowloon, Hong Kong, in the 13th century. One story has it that he aided the last emperor of the Song dynasty, an 8 year-old boy, in his flight from the invading armies of the Mongol ruler Kublai Khan in about 1380. Tam Kung with the rest of his Hakka community were executed by the Mongols for his patriotic efforts. Later he was deified and temples were built in his honor. Tam Kung Temple 谭公庙, Victoria, British Columbia, 19th century.

Tian Hou or Tin How 天后, the Empress of Heaven, is a semi-historical figure of the 10th century who became a goddess through her virtue and her power to save sailors from storms at sea. In America, she was probably the second most popular deity among early Chinese. She too has acquired numerous titles, like “Goddess of Heaven” and “Mazu” 妈祖 (Most Revered Mother). She can often be recognized by her empress’s headdress, a horizontal board with a row of tassels hanging down in front. Each of the three temples we discuss in this book has a statue of her, all sharing similar features. The Tin How Temple on Waverly Place in San Francisco is famous among Chinese worshipers and non-Chinese tourists. Although the current version of the San Francisco temple is not old, the city had at least two temples dedicated to Tian Hou before the 1906 Earthquake. In Chinese eyes, one or both of those Tian Hou temples ranked with the most sacred places in North America. Ng Shing Gung Temple 五圣宫, San Jose, California, 1880s-90s.

Tu Di 土地 the Earth God. Although rarely the main deity of any Daoist temple, He is present as a statue or name tablet in almost all of them. Learned Daoists point out that he is not a specific deity but an office filled by a benevolent, popular local soul. Ordinary people do not make this distinction, however. Shrines of Tu Di are everywhere – in homes, shops, temples, and even cemeteries, often located directly on the ground. He is depicted as an elderly, well-dressed man with a calm smile and a peaceful pose, usually seated. In California he seems to have had special importance among miners. This may be because, as god of all things in the ground, he controls deposits of minerals, including gold.. The nose of this particular image has been broken off. Won Lim Temple 云林庙, Weaverville, California, 1870s-80s.

The Gods of Chinese in North America 美洲早期华人庙宇神祇名录

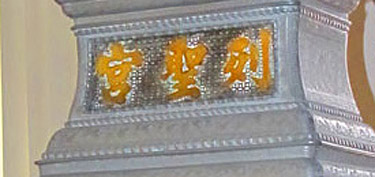

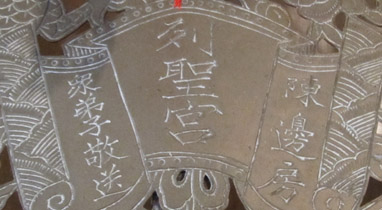

Numerous early Chinese temples in North America were not dedicated to a specific deity. Instead, they were called Leisheng Gong or, in Cantonese, Liet Sing Gung: “Temple of Many Gods.” [The word “sheng” is sometimes translated as “saints.” This is incorrect if used outside a Christian context. Although many Chinese deities are former mortals, after deification they have gained the authority of true divinities: that is, unlike Christian saints or angels, they are not only immortal but can exert their powers independently without the help or permission of any other deity.]

The Leisheng Gong name appears on or in at least 10 surviving Chinese temples in the U.S. and Canada: in Victoria, Seattle, and Lewiston in the Northwest and in Auburn, Bakersfield, Marysville, Nevada City, Oroville, Chico, San Francisco, and Weaverville in California.

In other cases, temples seem to have two names, representing either a transition from one name to the other or the coexistence of different functions. A transition process may be under way at two temples usually called by names indicating dedication to the North God, Beuk Aie in Lewiston and Bok Kai in Marysville. Those names have long been regularly used by white and Chinese residents. Yet neither temple has furnishings that show a primary focus on the North God, and both are still formally called “Leishenggong” on their lintel boards and in other ritual inscriptions.

In two cases, the relevant artifacts are portable and located in places of worship that may never have featured multiple deities. Currently in the well-known Tin How Temple in San Francisco and a non-public Gee How Oak Tin shrine in Seattle, these must have come from other, now-vanished temples in their areas.

In Weaverville, the use of two names may indicate not a transition but the coexistence of ritual functions. The Weaverville temple is known to modern visitors as Won Lim Miao, the Cloud Forest Temple. The name is an old one. However, it is not the poetic thought it appears to be but instead a reference to a ritual text of the Hong Shun Tong/ Chee Kung Tong secret society. Judging from other inscriptions at the temple, Won Lim often served intensely private, not to say secret, purposes. And yet its entrance also bears the Liesheng Gong name. A set of written rules preserved in the temple makes it clear that this other name is not a historical accident. The building was often open to public worship. The resulting cash, food, ritual goods, and fireworks were seen as important benefits by the local temple committee, which seems to have been under the thumb of the Hong Shun Tong.

Temples primarily of the multi-deity type include two of the most important and richly furnished in North America: the one now housed in the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association’s building in Victoria and the main temple at Oroville. The former seems to have already been a leisheng gong in 1885, when it was taken over by the newly established CCBA and rebuilt as a source of revenue. The latter has no other name. As far as is known, it was considered to be a multi-deity temple as early as 1863, the date of its earliest dedication board, which is also the second oldest known Chinese American artifact.

We are not sure whether the presence of a Leishenggong inscription on the front panel of the main altar from Grass Valley's former Hou Wang temple, now in the Firehouse Museum in Nevada City, represents a transition or an effort by a single-deity temple to accommodate devotees of other deities. Hou Wang, an minor deity worshiped mainly by Zhongshanese, might not have attracted other Cantonese, forcing the temple's owners to admit other deities.

Leisheng Gong or Temple of Many Gods 列圣宫, 何其多

Click on the image to see the complete object

Entrance Lintel Board, Oroville

Censer in Wugong set, CCBA, Victoria

Click on the image to see the complete object

Click on the image to see the complete object

Click on the image to see the complete object

Click on the image to see the complete object

Temple parade Fan, Seattle

Brass Censer Set, San Francisco

Portable shrine, Marysville

Altar Shrine Enclosure, Lewiston

Altar Facade, Grass Valley

Entrance Sign, Weaverville

Numerous early Chinese temples in North America were not dedicated to a specific deity. Instead, they were called Leishenggong or, in Cantonese, Liet Sing Gung: “Temple of Many Gods.” [The word “sheng” is sometimes translated as “saints.” This is incorrect if used outside a Christian context. Although many Chinese deities are former mortals, after deification they have gained the authority of true divinities: that is, unlike Christian saints or angels, they are not only immortal but can exert their powers independently without the help or permission of any other deity.]

The Leishenggong name appears on or in at least 10 surviving Chinese temples in the U.S. and Canada: in Victoria, Seattle, and Lewiston in the Northwest and in Auburn, Bakersfield, Marysville, Nevada City, Oroville, San Francisco, and Weaverville in California.

In other cases, temples seem to have two names, representing either a transition from one name to the other or the coexistence of different functions. A transition process may be under way at two temples usually called by names indicating dedication to the North God, Beuk Aie in Lewiston and Bok Kai in Marysville. Those names have long been regularly used by white and Chinese residents. Yet neither temple has furnishings that show a primary focus on the North God, and both are still formally called “Leishenggong” on their lintel boards and in other ritual inscriptions.

In two cases, the relevant artifacts are portable and located in places of worship that may never have featured multiple deities. Currently in the well-known Tin How Temple in San Francisco and a non-public Gee How Oak Tin shrine in Seattle, these must have come from other, now-vanished temples in their areas.

In Weaverville, the use of two names may indicate not a transition but the coexistence of ritual functions. The Weaverville temple is known to modern visitors as Won Lim Miao, the Cloud Forest Temple. The name is an old one. However, it is not the poetic thought it appears to be but instead a reference to a ritual text of the Hong Men/ Chee Kung Tong secret society. Judging from other inscriptions at the temple, Won Lim often served intensely private, not to say secret, purposes. And yet its entrance also bears the lieshenggong name. A set of written rules preserved in the temple makes it clear that this other name is not a historical accident. The building was often open to public worship. The resulting cash, food, ritual goods, and fireworks were seen as important benefits by the Hong Men leadership.

Temples primarily of the multi-deity type include two of the most important and richly furnished in North America: the one now housed in the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association’s building in Victoria and the main temple at Oroville. The former seems to have already been a leishenggong in 1885, when it was taken over by the newly established CCBA and rebuilt as a source of revenue. The latter has no other name. As far as is known, it was considered to be a multi-deity temple as early as 1863, the date of its earliest dedication board, which is also the oldest known Chinese American artifact.

We are not sure whether the presence of a Leishenggong inscription on the front panel of the main altar from Grass Valley's former Hou Wang temple, now in the Firehouse Museum in Nevada City, represents a transition or an effort by a single-deity temple to accommodate devotees of other deities. Hou Wang, an minor deity worshiped mainly by Zhongshanese, might not have attracted other Cantonese, forcing the temple's owners to admit other deities.

Leishenggong 列圣宫 (Cantonese Liet Sing Gung): Multi-Deity Temples

Click on the image to see the complete object

Entrance Lintel Board, Oroville

Censer in Wugong set, Victoria

Click on the image to see the complete object

Click on the image to see the complete object

Click on the image to see the complete object

Click on the image to see the complete object

Temple Weapon Fan, Seattle

Brass Censer Set, San Francisco

Temple Palanquin, Marysville

Altar Shrine Enclosure, Lewiston

Altar Facade, Grass Valley

Entrance Sign, Weaverville

CONFERENCE PROGRAM

Place: Yuba County Library, 303 Second Street, Marysville, CA

Day 1: 3/12/2016 (Saturday)

Panel A. 1:45-3:20

"Active Temples: Management, Preservation, and Promotion"

Chair: Chuimei Ho (Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee, Bainbridge Island, WA)

Welcoming speech: Richard Lim (Marysville Chinese Community/Bok Kai Temple, Marysville, CA)

Speakers:

“The Success of the Bok Kai Temple”

“Kong Chow Temple of Los Angeles: Preserving the Spirit of the Homeland and the Spirit of the

“The Tam Kung Temple in Victoria, B.C.”

Commentators:

Victor Yue (Chinese Temple & Taoist Heritage Studies, Singapore)

Gordon Tom (Chinese American Museum of Northern California, Marysville)

Sue Cejer-Moyres (Yuba County Historic Resurce Commission, CA)

Panel B. 3:50- 5:10

"Inactive Temples: Preservation and Touristic Potential"

Chair: Brian Tom (Chinese American Museum of Northern California, Marysville)

Speakers:

Victor Yue (Chinese Temple & Taoist Heritage Studies, Singapore)

"Chinese Temples in Singapore - Decline and Resurgence of Interest in our Cultural Heritage"

Commentators:

Gerrye Wong (Chinese Historical & Cultural Project, History/San Jose, San Jose, CA)

Briana Struckmeyer (Visit Yuba-Sutter and the Yuba-Sutter Chamber of Commerce, CA)

Reception & Forum: 6:30-8:30 pm

Forum: “Where do we go from here? – Brainstorming and Networking.”

Co-chair: Brian Tom (CAMNC-Marysville) & Chuimei Ho (CINARC)

Day 2: 3/13/2016 (Sunday)

Panel C. 9:00- 10:15

"Museums: Preservation and Touristic Potential of Temple Heritage Collections"

Chair: Jonathan H.X. Lee (Asian-American Studies, College of Ethnic Studies, San Francisco State University)

Welcoming Speech: Councilman Bill Simmons, Marysville

Speakers:

“Chinese Temple Exhibit at the Courthouse Museum: Benefits and Challenges”

“Significance of the Bo On Tong Altar in the Exhibits of the Clatsop County Historical Society”

Commentators:

Wallace Hagaman (Nevada County Historical Society--Fire House No. 1 Museum, CA);

John Adams (Discover The Past, Victoria, B.C.)

Panel D. 10:45- 12:00

"Chinese-American Museums: Role, Funding, and Interpretation of Religious Collections."

Chair: Sarah Lim (Merced County Court House Museum, Merced, CA)

Speakers:

“Role of Chinese American Historical Museum (CAHM, aka Ng Shing Gung, “Temple of the Five Deities”)

“Los Angeles Chinatown as a Living History Museum, and the Role of the Kong Chow Temple

“The Role of Chinese American Museums and Chinese Temples and Religion”

Commentators:

Paul G. Chace (Paul G. Chace & Associates, Escondidio, CA)

Concluding Remarks:

Lyle Wirtanen (Nez Perce County Historical Society, Lewiston, ID)

Richard Lim (Marysville Chinese Community/Bok Kai Temple, Marysville, CA)

Dinner: 6:30-8:30

Optional Events:

CONFERENCE

Temples and Museums: Managing and Interpreting Historic Cultural Assets

庙宇-博物馆会议: 管理与傳承

Date: March 12-13, 2016

Conference Organizers

1. Marysville Chinese Community/Bok Kai Temple,

Marysville, CA.

http://www.bokkaitemple.com/

2. Chinese American Museum of Northern California,

Marysville, CA.

http://www.chineseamericanmuseum.com/

3. Chinese-American Museum of Chicago – Raymond

B. & Jean T. Lee Center, Chicago, IL.

http://www.ccamuseum.org/

4.Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee

(CINARC), Bainbridge Island, WA

http://www.cinarc.org/

3

2

1

4

The Tam Kung Temple in Victoria, B.C.

John Adams

Owner, Discover The Past, Victoria, B.C. Canada

Abstracts of Presentations

Re-constructing a Chinese Temple in Lytton British Columbia

Lorna Fandrich

Owner, Kumsheen Whitewater Rafting, Lytton, B.C

Weaverville's Won Lim Temple and Its Recent History

Jack Frost

California State Department of Parks and Recreation

Weaverville Won Lim Temple

RoIe of Chinese American Historical Museum

(CAHM, aka Ng Shing Gung, “Temple of the Five Deities”)

Christian Jochim (Secretary) & Allan Low (Treasurer)

Chinese Historical and Cultural Project (CHCP), San Jose

Funding for CAHM

Interpretation

Saved, Preserved, and Hidden: Fresno’s Chinese Altars

Ruth Lang

Operations and Collections Manager, Fresno Historical Society, Fresno, CA

The Success of the Bok Kai Temple

Ric Lim

President, Marysville Chinese Community

Chinese Temple Exhibit at the Courthouse Museum:

Benefits and Challenges

Sarah Lim

Director, Merced County Court House Museum, Merced, CA

Kong Chow Temple of Los Angeles: Preserving the spirit

of the homeland and the spirit of the pioneers of Chinatown

(Panel A)

Eugene Moy

Board Member, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA

My presentation at the panel will discuss:

a) the relevance of the old temple, which includes representations of various gods and spiritual figures, and temple

furnishings such as altars and ritual objects, to the current Chinatown community.

b) how the Kong Chow Association maintains and presents the temple to the community.

c) the significance of newer temples resulting from more recent migrations.

d) thoughts on long term goals for curation of Kong Chow Temple furnishings, and maintaining the temple as a cultural

and spiritual resource for the future.

Los Angeles Chinatown as a living history museum, and the role of the Kong Chow Temple and its collections in Chinatown’s future

(Panel D)

Eugene Moy

Board Member, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA

Significance of the Bo On Tong Altar

to the Exhibits of the Clatsop County Historical Society

Liisa (Arlene) Penner

Archivist, Clatsop County Historical Society, Astoria, OR

The Role of Chinese American Museums and

Chinese Temples and Religion

Brian Tom

Director, Chinese American Museum of Northern California, Marysville, CA

Chinese Heritage Temple Collections in Lewiston, Idaho

Lyle Witanen

former Director, Nez Perce County Historical Society, Lewiston, ID

I have served Tianhou for two Decades,

for Myself and Chinese Traditions

Susan Woon

Keeper, Tin How Temple, San Francisco

Bok Kai Temple, Marysville, CA

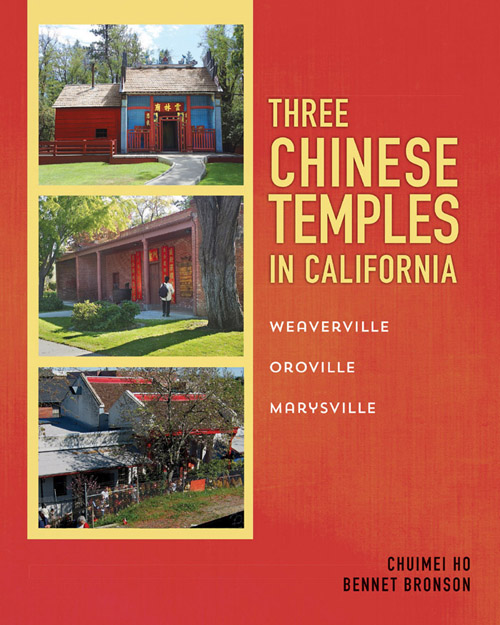

Publication in 2016

Three Chinese Temples in California:

Weaverville, Oroville, Marysville

Authors: Chuimei Ho, Bennet Bronson

List Price: $24.99

8" x 10" (20.32 x 25.4 cm)

Full Color on 104 pages

ISBN-13: 978-1519517135

ISBN-10: 1519517130

LCCN: 2016901276

BISAC: History / United States / 19th Century

Published by CINARC, Seattle

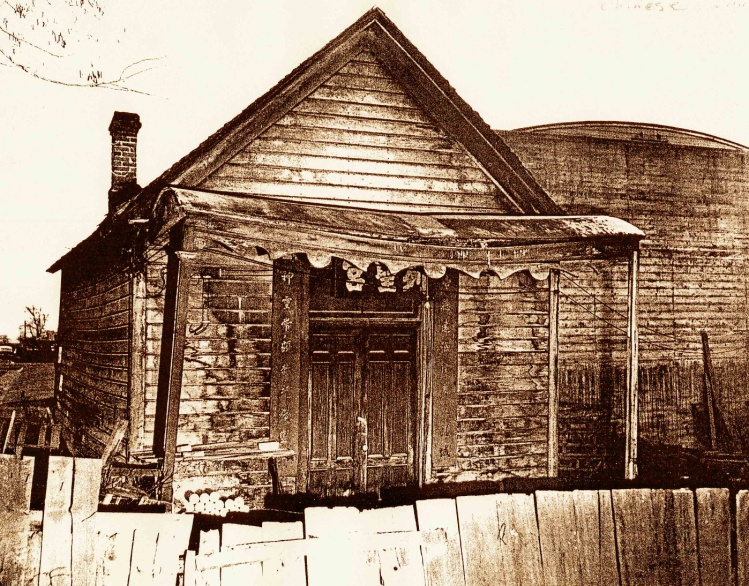

Beuk Aie Temple, 1880s

Memorial at the Snake River site 2012

San Jose History Park

Chinese Temples of Singapore -

Decline and Resurgence of interest in our cultural heritage

Victor Yue

Founder, Chinese Temple & Taoist Heritage Studies, Singapore

1. The decline of temple interest, probably other than Hong Kong and Taiwan, is being experienced in Chinese

The decline of temple interest, probably other than Hong Kong and Taiwan, is being experienced in Chinese

communities all over the world. Many older overseas Chinese communities have gone through and are still experiencing such phases.

2. In South East Asia (Nanyang), many Chinese who were traditionally Buddhists and Taoists (including folk religion) have become Christians. After a generation or two, many have lost knowledge of their heritage. In Singapore, the removal of some old Chinese tombs has renewed interests in the Chinese culture.

In South East Asia (Nanyang), many Chinese who were traditionally Buddhists and Taoists (including folk religion) have become Christians. After a generation or two, many have lost knowledge of their heritage. In Singapore, the removal of some old Chinese tombs has renewed interests in the Chinese culture.

3. At the same time, in places like Indonesia, there is a strong renewed interest after the “liberation” of the Chinese culture in recent years. Temples there started making contacts with Chinese temples overseas. Chinese cultural activities too, such Lion and Dragon Dance, Wushu, Chinese music such as Nanyin. Facebook quickens the process of communications and Google Translate helps.

At the same time, in places like Indonesia, there is a strong renewed interest after the “liberation” of the Chinese culture in recent years. Temples there started making contacts with Chinese temples overseas. Chinese cultural activities too, such Lion and Dragon Dance, Wushu, Chinese music such as Nanyin. Facebook quickens the process of communications and Google Translate helps.

4. There is a renewed interest in the young on their heritage.

There is a renewed interest in the young on their heritage.

5. The young are literate and savvy in the world of internet communications. Email Forums, Web Sites, Facebook, Instagram, Youtube and Vimeo have helped them getting to know more about the ancient Chinese culture.

The young are literate and savvy in the world of internet communications. Email Forums, Web Sites, Facebook, Instagram, Youtube and Vimeo have helped them getting to know more about the ancient Chinese culture.

6. They are not shy in joining groups of strangers. More could speak and write English and Chinese. Many are doing translations for the benefit of their people. Others use Google Translate for a gist.

They are not shy in joining groups of strangers. More could speak and write English and Chinese. Many are doing translations for the benefit of their people. Others use Google Translate for a gist.

7. There are other people who are seeking the ancient Chinese philosophy. They are very knowledgeable and articulate. There are great English translations.

There are other people who are seeking the ancient Chinese philosophy. They are very knowledgeable and articulate. There are great English translations.

8. Email, web-based forums and facebook groups offer an

Email, web-based forums and facebook groups offer an

international gathering to share knowledge and understanding

of practices in different localities around the world.

9. Our old temples are our tangible heritage.

Our old temples are our tangible heritage.

The practices within our temples are our intangible

heritage. It is our culture heritage that we must

try to preserve. Chinese temples are similar in

different places, but they are repositories of

different histories.

Yue Hai Qing Miao 粤海清庙 –

A Teochew 朝州Temple, Singapore

Ng Shing Gung

1880s

Ng Shing Gung demolition, 1949

The Reconstructed

Ng Shing Gung

Who else were at the conference?

Quite a few. Most have a professional interest in Chinese cultures, religious art, and cultural heritage. Here is the list of pre-conference registered attendees:

California

. Lucy Bowen, Independent Scholar, Menlo Park.

. Pamela Bulahan, Isleton Brannan-Andrus Historical Society, Isleton.

. Pat Camarena, Yuba County Historic Resource Commission, Marysville.

- Teresa Chan, Independent Attendee, Stockton.

- Teresa Chin, Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation.

. Yvonne Ching, Chinese Historical & Cultural Project, San Jose.

. Suellen Cheng, Scholar, Los Angeles.

. Linda Sun Crowder, California State Univeresity at Fullerton, Brea.

. Carol Donaldson, Yuba County Historic Resource Commission, Marysville.

. Sharon Fong, Isleton Brannan-Andrus Historical Society, Isleton.

. Debbie Gong-Guy, Chinese Historical & Cultural Project, San Jose.

. Carol Green, Isleton Historical Society, Isleton.

. Chuck Hasz, Isleto Brannan-Andrus Historical Society, Isleton.

. Lynne Hasz, Isleton Brannan-Andrus Historical Society, Isleton.

. Connie HigdonGannon, Greenspace-The Cambria Land Trust, Cambria.

. Munson Kwok, Scholar, Los Angeles.

. Lily Leung, Tin How Temple, San Francisco.

. Eileen Leung, Locke Boarding House Museum, Davis.

. Sandy Lim, Marysville Chinese Committee/Bok Kai Temple.

. Gerry Low-Sabado, Chinese American Citizens Alliance, Salinas Lodge.

. Georgia Lord Watanabe, Independent Attendee, Barstow.

- Irving Mallard, Independent Attendee, Smartsville.

- Lori Martin, California State Parks - Weaverville Joss House, Shasta.

. Sylvia Sun Minnick, Historian-Scholar, Stockton.

. Wai Moy, Independent Attendee, Pleasanton.

. Sally Ooms, Isleton Brannan-Andrus Historical Society, Isleton.

. Nancy Ostrom, Chico Museum, Chico.

. Anne Peterson, Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation, Santa Barbara.

- Randy Sabado, Independent Attendee, Salinas.

. Mae Schoenig, Diablo Valley Chinese Cultural Association, Martinez.

- Susan Sing, Independent Attendee, Los Angeles.

. Kathy Smith, Yuba County Historic Resource Commission, Marysville.

. Elizabeth Steward, Friends of the Bok Kai Temple and Historic Chinatown, Chico.

. Pam Sweet, Isleton Brannan-Andrus Historical Society, Isleton.

. Jan Winbigter, Independent Attendee, Sacramento.

. Brenda J. Hee Wong, Chnese Historical & Cultural Project, San Jose.

- Anthony Wu, Independent Attendee, Stockton.

. Lisha Yang, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Idaho

. Garry Bush, Nez Perce County Historical Society, Lewiston.

. Debi Fitzgerald, Lewis Clark State College, Lewiston.

Nevada

. Michelle Lord, Nevada State Museum, Las Vegas.

Oregon

. Christina Sweet, Kam Wah Chung Oregon Parks & Recreation Department, John Day.

Washington

. Frederick Yee, Independent Attendee, Bellevue.

CANADA

Acknowlegements: helpful individuals and Institutions

Conference venue: Yuba County Library, Second Street, Marysville

Chinese Pluralities Through the Americas

An International Conference of the Chinese Historical Society of America

Conference Dates: October 6–8, 2017

Location: Hilton San Francisco

750 Kearny Street (Financial District)

San Francisco, CA 94108

Day 3 Sunday, October 8, 2017

4-5:50 pm Concurrent Sessions 6. Room Columbus III

Moderator: Chuimei Ho, Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee (CINARC)

Chuimei Ho, CINARC

R. Gregory Nokes, Independent Researcher.

Davi Y. Lei, The Chinese Performing Arts Foundation.

Ben Bronson, CINARC.

What panelists will talk about ...

The Social Role of Traditional Chinese Religion in Nineteenth Century America

a panel discussion featured in

David Y. Lei

Performing for the Gods: Opera

in Traditional Chinese Religion

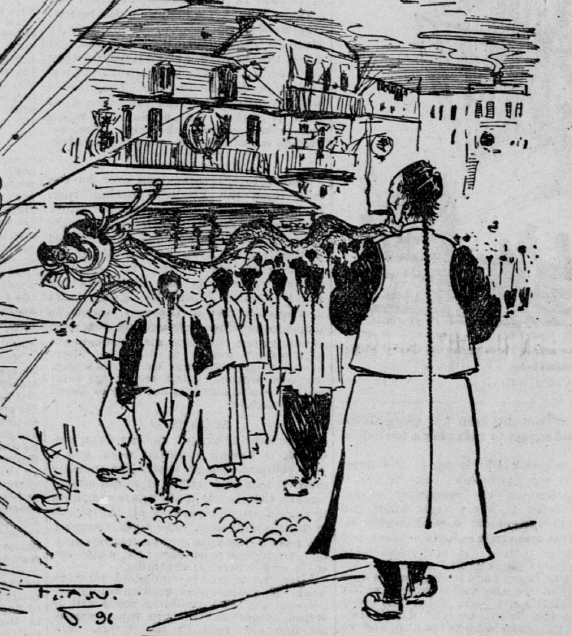

Cantonese opera was developed from a long line of folk religions - from Shaman (Wu - 巫 ) rituals and Nuo masks and rituals (儺). In traditional China, temple fairs always held opera performances, with the stage facing the temple for deities to enjoy. But the programs, such as “The Eight Immortal Birthday Greetings” and lion dancing were also intended to bring auspiciousness to the community. Cantonese opera was also an important educational channel from where the public learn history, culture, ethics, morals, and religion, just like what movies and TV do these days. But more importantly, traditional Chinese theatres, whether they were temporary or permanent, were social places for the community. They were communal affairs where organizers, performers, audience and even vendors each had their role in making it happen. Noisy and chaotic both on and off the stage, everyone seemed to know what was going on.

Since the coming of the 123 members of the Hong Fook Tong in 1852, Cantonese opera has thrived in San Francisco, outlasting all the other ethnic theaters that used to be prevalent during gold rush days. Cantonese opera is unique from other Chinese regional operas in that the actors were highly trained in commedia dell'arte and can improvise a different daily program, sometimes acting out the current news. This drew the audience and community together on a daily basis, becoming the talk around the water cooler.

The Social Role of Traditional Chinese Religion in Nineteenth Century America

R. Gregory Nokes

Massacre for Gold – Religious Responses from Communities in Lewiston and Beyond

”The little–known massacre of as many as three-dozen Chinese gold miners on the Oregon-Idaho border in 1887 was the worst of the many crimes committed by whites against Chinese immigrants in the American West.

Only in recent years, has the severity of the crime been publicly recognized with a memorial to the slain miners, erected by an inter-racial committee. But there’s credible reason to believe the Chinese community in Lewiston, Idaho, took steps at the time to honor the victims, although their efforts weren’t known or appreciated in the white community.

The crime occurred in the depths of remote Hells Canyon, the deepest canyon in North America, when a gang of white horse thieves attacked a group of unarmed Chinese who were mining gold along the Snake River. The gang could easily have robbed the Chinese of their gold and left them helpless to do anything about it. But the gang’s actions went far beyond a robbery to a savage act of racial hatred. The killers proceeded to slaughter every Chinese in the camp, throwing the bodies into the north-flowing river where some of them surfaced at Lewiston, sixty-five miles to the north.

There was an investigation of sorts, and a trial. But the accused were found innocent, while the ringleaders escaped and were never caught. The crime was covered up for more than a century.

In 2012, after the crime had been rediscovered, a committee of Chinese Americans, Caucasians and Native Americans, raised money for a memorial overlooking the river at the massacre site. It was dedicated in 2012 by Master E-Man, a Taoist priest from Los Angeles, who told the large gathering he had first cleansed the site of its evil spirits.

However, there is also is reason to believe that the Chinese community in Lewiston, staggered by the murder of so many of their members, renovated and furnished the Lewiston temple to honor the slain miners.

More about the panelists

R. Gregory Nokes

David Y. Lei

Chuimei Ho and Ben Bronson

Co-founders of CINARC, based in the Seattle area.

Ben Bronson

The Sudden Disappearance of Folk Daoism in Chinese America

Perhaps the greatest puzzle in the early history of Chinese temples on this continent is why they disappeared. In the nineteenth century, they dominated most North American Chinatowns, physically as well as in the minds and lives of many Chinese immigrants. But after the second decade of the twentieth century almost all were gone. The question is, why? And why in North America, at a period when traditional Chinese religion was thriving in much of Asia? This paper explores several possible explanations: Christian opposition, racist hostility, Chinese progressive thought, the benefits of appearing to be progressive, and—perhaps most important—the relative absence of women who, in Chinese as in many other cultures, have been the mainstays of popular religion.

Chuimei Ho

The Tachiu Ceremony in San Francisco and Sacramento –

A Public Event that was More Important than Chinese New Year

Tachiu ceremonies 打醮 were an extraordinary type of religious activity among American Chinese before 1920; no fewer than seven cities and towns held such ceremonies regularly. The first few tachiu might have been triggered by the need to pacify the spirits of victims of disasters: in 1865 Sacramento Chinese held its first tachiu after the steamboat Yosemite exploded at Rio Vista, killing 30 Chinese along with many others. Six years later in Los Angeles, when 17 Chinese were killed in a riot, that community too held a major tachiu.

But not every early tachiu was connected with tragedies. San Francisco’s Chinatown saw its first tachiu in 1868; it seems to have been more of a thanksgiving than a memorial. San Francisco is also unusual in having sometimes had more than one tachiu in a year, celebrated by multiple competing organizations. These included several of the Six Companies as well as the Chee Kung Tong, the Four Brothers Association, and several others.

My presentation will discuss patterns of tachiu performances and their economics in connection with changes in the communities involved.

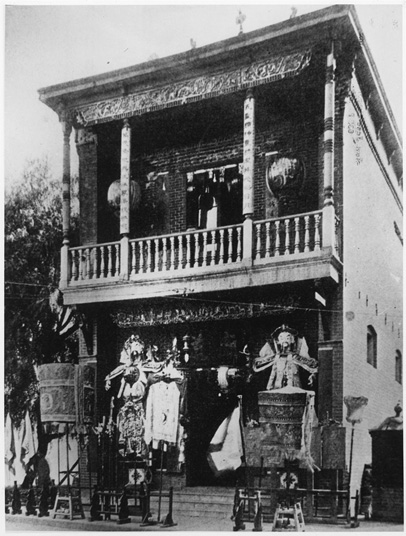

January 23, 1896, Dragon Dance in San Francisco's Chinatown

The building on the left displayed two large figures at the entrance, a sign of a tachiu ceremony in progress. Identified as Spofford Alley, San Francisco. Because of the Nationalist flags and the style of the gaments, the photograph must have been taken after 1912.

Bancroft Library,

UC Berkeley. 1905.17500.v29

| ||||||

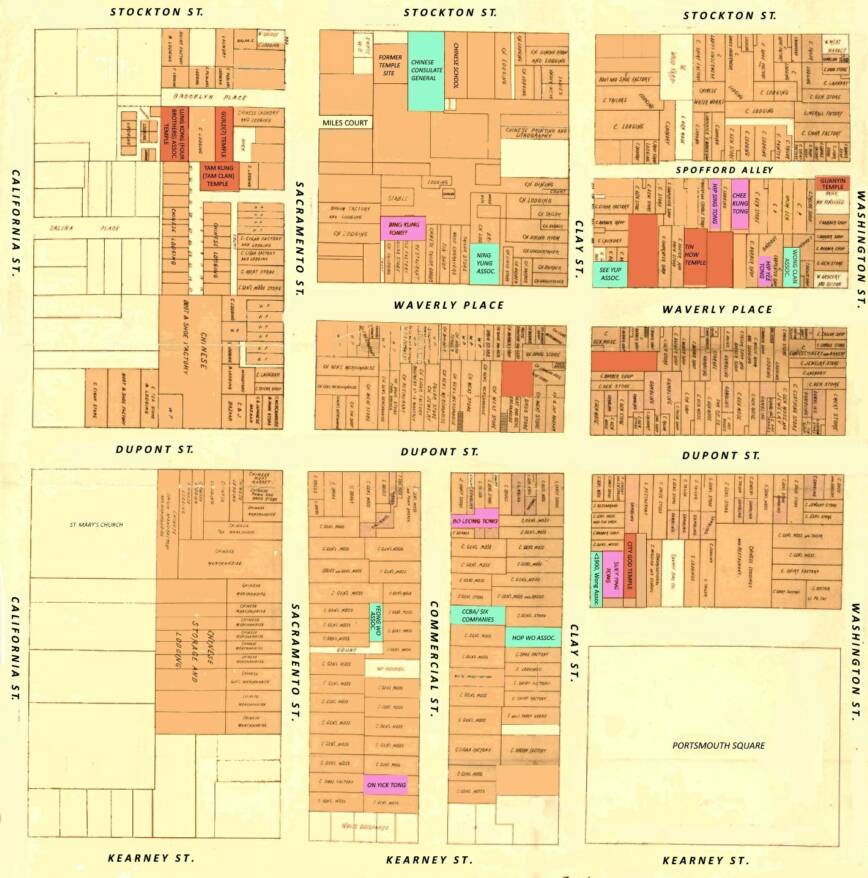

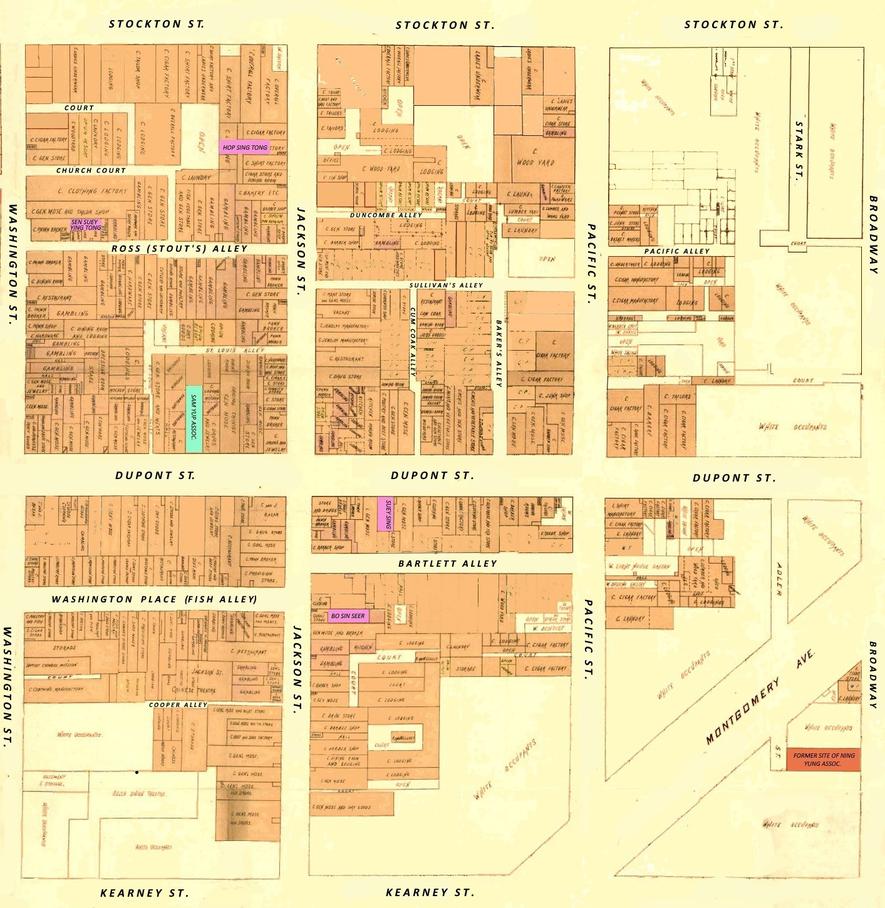

The following map, divided into north and south parts, represents San Francisco's Chinatown in 1905, on the eve of the great earthquake and fire that destroyed it. The rebuilt Chinatown of the present day, visited by tens of millions of tourists and the heart of Chinese America in the eyes of earlier Chinese immigrant families, has the same footprint as the 1905 version but is otherwise very different. For one thing, it is filled with "Chinese" architecture: tiled roofs with upturned ends, coffered ceilings over recessed balconies, wall decor featuring dragons, and lions, and so forth. None of these existed in 1905 but by 1910 they were everywhere, even in other Chinatowns. Another big change: the new Chinese quarter of the city was cleaner, better organized, and perhaps less atmospheric than the 19th century Chinatown.

The editors created this map in the course of research into early Chinese temples and the institutions--public-spirited committees, region-of-origin associations or huiguan, and secret societies--that hosted them. Almost all of the organizations shown here maintained public temples or semi-private shrines. One of the best-known was and is the Guandi Temple of the Kong Chow Huiguan, now on Stockton Street but until the 1960s at Pine and Kearney, outside the map. Another of the best-known was that of the Ning Yung Huiguan, formerly on Broadway and Montgomery but moved to Waverly Place in about 1900. Perhaps the most splendid of all Chinese American temples, it was leveled by the Earthquake and never rebuilt as a temple, although the Association had no trouble financing a fine new headquarters in approximately the same place. It seems to have lost interest in this aspect of traditional religion.

The map is based on the well-known 1885 Board of Supervisors' map but updated with information from contemporary newspapers, the 1905 Sanborn Fire Maps, the 1905 Chinese Telephone Directory for San Francisco, and the 1903 Directory of Chinese Businesses. Because the Supervisors' map was drawn up with strongly anti-Chinese objectives, it was colored to emphasize social evils like opium use, gambling, and prostitution, much of that data coming from unknown but questionable sources. We have recolored the map to eliminate those prejudiced emphases, modified the boundaries of Chinese and White settlement, updated street names to those used in 1905, and added new locations for temples ("joss houses") and other institutions. The map is a work in progress, The editors expect to update it several times in the coming year as our research into Chinese American temples progresses.

Key:

Cream = Streets and non-Chinese residence/use

Tan = Chinese residence/use

Red = Temples

Blue = Associations/Huiguan

Pink = Secret Societies

Chinatown, San Francisco, 1905, Northern Part

(to read more .. go to Gum Saan Journal, Vol.30, 1:70-82, Chinese Historical Society of Southern California)

The Greatest of All Chinese Festivals

Chuimei Ho, Bennet Bronson, and Master E-man

“There is one festival which is of more importance even than the Chinese New Year, and it is celebrated in great eclat once in three years. This feast of Ah Dieu is, to “John”, what Fourth of July is to the small boy…” J. Torrey Connor, Los Angeles Herald Illustrated Magazine, March 2, 1902.

Large statues to be burnt at a ta chiu festival,

Los Angeles, ca. 1900. California State Library.

Priests in San Francisco's Chinatown, ca. 1900. Bancroft Library, Berkeley.