| ||||

CHINESE SECRET SOCIETIES / "FREEMASONS"

美加早期的华人秘密社会

Such raids did not improve the public image of even the least violent and most public-spirited secret societies. Yet it is a mistake to view any such society solely through the lens of criminal justice. Most were much more than mere lairs of Mafia-style gangsters. Many were law-abiding, with a middle-class membership. They focused on charity, conflict resolution, and assisting members in relations with the non-Chinese world. In almost any Chinatown for at least part of its history, one or more secret societies were at the center of community life. They often had more power than any other immigrant Chinese organization, including regional, clan, and family name groupings, as well as the supposedly dominant Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association 中华会馆.

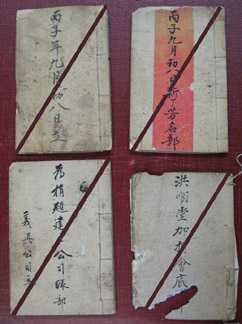

A 19th Century Chinese Secret Society Manual in Clinton, B.C.

加拿大卑斯省克林顿天地会会簿

In 2009 the editors first visited Clinton in British Columbia, located on the Cariboo trail that in the 1860s-1890s led from the southern Fraser River to the rich gold fields around Barkerville and Quesnel Forks. In those days, the population of the region was devoted almost entirely to gold mining, and more than half were Chinese.

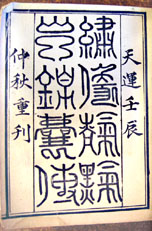

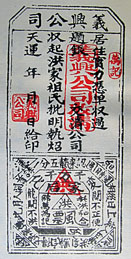

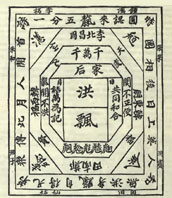

Title page: "Illustrated Manual of the Heaven and Earth Society. Printed in

the Autumn of the Renchen -Tianyun year." [cyclical date: 1892]

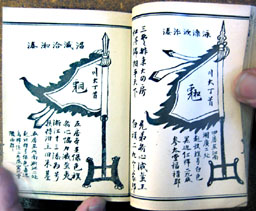

Right The flag for the Fourth of the Later Five Lodges. The large central character is a made-up word that combines “tiger” with “harmony”. The latter is the designated character for the Fourth Lodge. On its right are four characters that read “stream”, “large”, “person”, and “head”. These are the Society’s signature truncated versions of the phrase, “follow and practice the way of Heaven,” popular among underground societies in China for more than a millennium.

Left The flag for the Fifth of the Later Five Lodges. The design is identical to that of the Fourth Lodge with the compound word made up from “tiger” and “together”. The poetic verses summarize the identity and sovereignty of the Fifth Patriarch who headed the lodge.

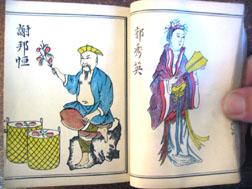

Right Wu Dedi. One of the Society’s Former Five Patriarchs, shown here in secular garb. In some accounts he is referred to as one of the five surviving monks of the Shaolin Monastery’s Southern Branch in Fujian.

Left Wu Tiancheng. Leader of the Society’s Later Five Patriarchs. Sometimes identified as a monk from the Baozhu Si [Precious Pearl Temple] in Guangdong.

Right Guo Xiuying, widow of Zheng Junda (an early leader of the Society killed by the Yongzheng government in a campaign), who together with Zheng’s sister threw herself into a river in Hubei when pursued by the Qing army. The bodies of the two sisters-in-law were recovered by a fisherman, Xie Bangheng.

Left Xie Bangheng, a fisherman and incognito Ming loyalist who recovered the bodies of Guo Xiuying and Zheng’s sister. Xie then built the “Sisters-in-Law” Temple on the riverside. He was honored as one of the five “benevolent heroes” of the Society.

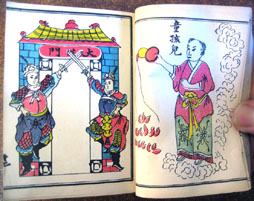

Right Tonghai Er, also known as the Red Boy. A character in The Journey to the West, the Red Boy was the son of the Bull Demon-King and Princess Iron Fan. Full of mischief and skilled in martial art, he was eventually subdued by the Buddhist goddess, Guanyin. Although he was not a regular deity in the pantheon of the Society, it is possible that the Clinton branch believed in evoking his spirit for initiation ceremonies.

Left View of one of the three gates that a new member must pass during the initiation ceremony. The two guards hold up swords to signify the “mountain of swords” test for initiates.

Is the manual unique? No. Modern copies with a very similar text are widely used in Hong Kong. Cai Shaoqing says that there are earlier copies, representing several versions, in libraries in Europe, North American, Australia, and China itself (Cai 2002, p 33). The Clinton version bears a cyclical date equivalent to 1892, which makes it later than several others, including the one reproduced by the pioneering Dutch scholar, Gustave Schlegel, in 1866. Most versions seem not to include images of deities and the founders of the Tiandihui. The Clinton version does include such images. Its colors are bright, and the condition, except for an eaten-away corner, is excellent.

We do not know whether other copies of the1892 version exist. The editors of this website, as well as Mike Brundage on behalf of the Clinton Museum, would be grateful for any information that our readers may have.

Lily Chow, Sojourners in the North, Prince George, BC: Caitlin Press, 1996

Cai Shaoqing On the Overseas Chinese Secret Societies of Australia, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 4, 1: pg 30-45, 2002

Gustave Schlegel, Thian Ti Hwui: the Hung League or Heaven-Earth League: A Secret Society with the Chinese in China and India, 1866

W. P. Morgan, Triad Societies in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Government Press. 1960.

No Chinese organization in 19th century BC is likely to have publicly called itself "Tiandihui," but several spinoff/daughter organizations in the region used Tiandihui rituals and regarded themselves as its heir. Among the oldest was the Hung Mun (= Hongmen, 洪 門) or Chee Kung Tong (= Zhigongtang, 致 公 堂 ), which--as discussed elsewhere on this page--assumed great importance among late nineteenth century Chinese North Americans. According to Lily Chow, there were Chee Kung Tong lodges in Quesnel, Quesnel Forks, Barkerville, and other gold-rush towns in the interior of British Columbia. We may assume that the Clinton manual was used by one such lodge.

One of the high points of Clinton is the excellent Clinton Museum 克林顿博物馆. We were guided through the museum’s rich historical collection by the curator, Mike Brundage

<clintonmuseum@telus.net>. While looking through the Chinese part of that col-

lection, we made a discovery: a small woodblock-printed book in Chinese characters

that appears to be an early edition of a membership manual for a famed secret organ-

ization, the Heaven and Earth Society or Tiandihui (天 地 會).

The Tiandihui came into existence in China in the late 17th century. It had two main

goals: (1) mutual aid among members and (2) resistance to the Manchus, whose alien

Qing Dynasty ruled China from 1644 to 1911. Because the Qing emperors saw the

Tiandihui as dangerously subversive and thus persecuted it mercilessly, the Society

stayed deep underground. In China during the imperial period, entire families would

have been executed solely because a member possessed a manual like the one in

Clinton. Outside China, in Hong Kong, Southeast Asia, Australia, and America, the

danger was not so acute, and the Society and allied organizations not only dared to

show themselves but often became, in slightly altered form, the social foci of overseas

Chinese communities. A number of early Tiandihui manuals survive in those places.

All are heavy with rituals, utilizing many legends and historical stories.

“Tianyun”--Secret Dates for a Revolutionary Cause

'天运' 年号背后的革命意识

Outside the front door of the Won Lim Temple 雲林庙 or"Joss House" in Weaverville 加州威弗维尔镇, California, is a couplet carved on vertical wooden boards, with characters in dark blue against a gilt background [Fig. 1]. The boards bear a short, two-line Chinese poem conveying conventional good wishes. However, the left board also bears a date, “Tianyun jiaxu ...” The use of Jiaxu is not a surprise: it is a year in the Chinese cyclical dating system, equivalent to 1874 [Fig. 2]. The use of Tianyun, on the other hand, is astonishing. Meaning “Cycle of Heaven,” it appears in the position, right before a date, that in those days was reserved for the name of the current emperor. Putting any other characters in that spot implied that the writer was in rebellion against the rulers of China.

The Chinese imperial government did not take such matters lightly. The presence of a Tianyun date, even if used in private, meant death for the writer plus, in all probability, his entire family. And yet in Weaverville the date was used publicly, on the front of a popular temple. What was going on?

The Tianyun dates represent one of the few exceptions to the above. No emperor had used such a reign name in the past 2000 years. Those who did use it were members of secret societies affiliated with the Tiandihui 天地会: in North America, the Hongmen 洪门 or Chee Kung Tong 致公堂. As early as the 17th century, rebels are supposed to have used Tianyun dates secretly to show their opposition to their rulers, the Qing Dynasty founded by China's Manchu conquerors. It was a serious matter in the eyes of those conquerors. Persons daring to use a Tianyun date were executed. Persons knowing that such a date was in use, without reporting it to the authorities, would also have been severely punished.

The situation was not so dangerous in North America. Many—in some places, most—Chinese immigrants belonged to secret societies with anti-Manchu sentiments, and imperial spies seem not to have been common in the remote areas where Chinese miners and railroad laborers worked. And yet the sponsors of the Won Lim Temple were going very far when they put a Tianyun date on a dedicatory board placed in front of the temple, out in the open for everyone to see. Were imperial spies as scarce as all that? Did the sponsors, who must have been a chapter of the Chee Kung Tong, feel safe for themselves, hidden in the mountains of northern California? What about their families back in China? Or is it possible that the dated board was originally inside the temple, in a spot where only trusted members of the society could see it?

The other Tianyun objects the editors have seen are all later than 1904, after the Hongmen society and its spinoffs had begun to move above ground. 1904 was the year when Dr. Sun Yat-sen 孙中山, later to be first president of the Chinese Republic, formally joined the Hawaiian branch of the Chee Kung Tong. His initial goal was to reorganize the society to sharpen its political agenda. In the next year he founded a new revolutionary organization, the Tongmenhui 同盟会, in Japan, while retaining close ties with the Hongmen/Chee Kung Tong. In the next few years, before the Manchu imperial government was overthrown in 1911, Dr. Sun himself used Tianyun dates on documents for both organizations.

The Special Archive at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver has several Chee Kung Tong membership slips with Tianyun dates equivalent to 1908. The former Chee Kung Tong headquarters in Victoria and Vancouver, both now owned by the Dart Coon clubs of those cities, have shrines with fine gilded carvings made, according to their Tianyun dates, after 1905 [Figs. 4-5].

For further information about the above-mentioned collections, readers should contact the relevant curators: Mike Brundage at the Clinton Museum; Linda Cooper in Northern Buttes District, Shasta (for the Won Lim Temple); Bill Quackenbush at the Barkerville Museum and Archives, and Christina Sweet at the Kam Wah Chung Museum. The editors owe thanks to Micah Sprouffske, also of Kam Wah Chung, for correcting the previous statement that Doc Hay was the same person as Wu Yuxue. He wasn't. As Sprouffske notes, why Lee used the Chinese family name Wu (Ng or Ing in Cantonese) is unclear.

For more on Tianyun date marks, it may be necessary to turn to Chinese-language sources. The editors are not aware of previous discussions of Tianyun dates in any English-language publication.

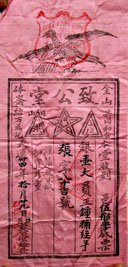

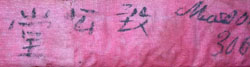

John Day in Oregon is the only other place in North America where, so far, we have seen Tianyun-dated objects. The archive of the Kam Wah Chong 金花昌博物馆Museum has two cloth slips issued to Jim Lee (伍郁學 Wu Yuxue), an associate of the famous herbal physician, Doc Hay. Lee had joined the Portland Chee Kung Tong in 1907 and had donated six dollars for the 1908 rebuilding of the earthquake-ravaged Chee Kung Tong headquarters in San Francisco [Figs. 7-8].

Fig. 1. Boards with dedicatory couplets flank the door of the Won Lim Temple (or Joss House), Weaverville, California.

雲林庙

For more than a thousand years, it had been the Chinese custom to date events by the year of the current emperor's reign. The American revolution of 1776, for instance, occurred in Qianlong 40, the fortieth year since Emperor Qianlong assumed the throne. As no Chinese-American or Chinese-Canadian writings survive from before 1851, one sees only four imperial reign marks on inscriptions and documents prepared in North America: Xianfeng 咸丰 (1851-1861), Tongzhi 同治 (1862-1874), Guangxu 光绪 (1875-1908) and Xuantong 宣统 (1909-1911). After that, Chinese and Chinese-Americans either dated events from the establishment of the Republic in 1911 or used the international BC/AD system.

Fig. 2 The board with blue characters on a gold background bears a Tianyun mark, equivalent to 1874 AD. The red board is dated to the same year, but bears a regular imperial reign mark, Tongzhi. Won Lim Temple, Weaverville. [Click to enlarge]

In any case, the Tianyun mark at the Won Lim Temple is probably the earliest example in the Americas. Most other examples come from British Columbia. The branches of the Chee Kung Tong at Barkerville and Quesnel Forks maintained excellent records and routinely dated them with Tianyun marks. Many such documents, some as early as 1884, are in storage at the office of the Barkerville Museum and Archives.

Elsewhere on this page we describe a unique illustrated manual of the Tiandihui (i.e., the Hongmen/Chee Kung Tong) that is now in the Clinton Museum, in Clinton, B.C. It bears a Tianyun date equivalent to 1892. [Fig. 3].

Fig. 3. Title page of Tiandihui manual, bearing a Tianyun date equivalent to 1892 AD. Clinton Museum, BC. 加拿大卑斯省.克林顿博物馆

Fig. 4. A lavishly carved gilt board with a central character “heart”. On one side is a Tianyun bingwu cyclical date equivalent to 1906. Dart Coon Club, Vancouver, BC. 加拿大温哥华

達權社

Fig.5. The left board of a couplet which bears a Tianyun dingwei cyclical date equivalent to 1907. This plaque is unusual in having an extra character, “three” between “tianyun” and the “dingwei” cyclical date. The presence of the “three” does not make obvious sense. Dart Coon Club, Victoria, BC.

加拿大 域多利 達權社

.

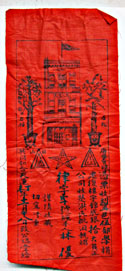

Fig. 6. Membership proof issued on the 29th of the 10th month, Tianyun 34th year [1909] by the Chee Kung Tong of Portland to Jim Lee in John Day, OR奧勒岡州. 约翰日市

Fig. 7. Receipt for Jim Lee's (Wu Yuxue's) $10 donation to the rebuilding of the Chee Kung Tong association in Chinatown, San Francisco. Dated “Tianyun dingwei the 18th day of the 11th month” [1907]

Membership Certificates Meant for Concealment 洪门致公堂腰牌

Certificates of membership in the Chee Kung Tong and allied organizations seem to have often been produced by printing on thin cloth, so that they could be hidden by sewing inside members' clothing. In 1891, a sensation was caused in San Francisco 三藩市 by the discovery of such a membership badge "sewn inside the lining of an undergarment" of an accused "highbinder",a fighter for a secret society. According to the Chicago Tribune (1894-11-25, p 43), this was "the first time in the history of San Francisco [that] evidence has fallen into the hands of the police authorities that reveals the true nature of the Chinese highbinder organizations."

It is interesting that membership certificates of the equally secret and subversive Gelao Hui of central and northern China also were printed on cloth. One was seized by the Shanghai Police in 1885. It is illustrated in a China Review article by the Brtish Consul, Playfair, in 1886.

Note: The photograph of the certificate in the University of British Columbia archives, which was taken by the editors, appears here in distorted form. We will remove the distortion when the UBC archives gives us permission to put an undistorted medium-resoluton image on line. As previously, we wish to thank Christinas Sweet at the Kam Wah Chung Museum in John Day, Oregon, for allowing us to see the Chee Kung Tong material in the Ing Hay collection.

Membership badge printed on cloth, San Francisco, 1891 三藩市

Membership badge printed on cloth, Victoria, BC, 1906

加拿大域多利

19th century Membership badge ion paper from West Malaysia 马来西亚

> Should the subject be taboo? 秘密社会可谈不可谈? 10/01/09

> A 19th century secret society manual in Clinton, B.C. 加拿大卑斯省天地会会簿 10/01/09

> "Tianyun"--secret dates for a revolutionary cause '天运' 年号背后的革命意识 07/22/10

> Membership certificates meant for concealment 洪门致公堂腰牌 08/13/10

> A meeting notice you couldn't refuse 见签岂有不到会 08/15/10

> The history of the Chee Kung Tong without the myths 致公堂来龙去脉 09/22/10

> The mother(s) of all secret societies 致公堂独步武林 09/22/10

> The mother society puts on a new face and changes her name 从洪门到致公堂 09/22/10, revised 12/27/13.

> The glory days of the Chee Kung Tong 1890年代致公堂如日冲天 09/22/10, revised 12/03/10.

> Sun Yat-Sen and the Chee Kung Tong: as early as 1897? 孙中山与致公堂1896 年结缘? 09/26/10,

> The Chee Kung Tong and the American Masons in Helena, Montana 喜连拿市致公堂 12/06/10

无故隐退 08/08/12

> The secret society murder of Seid Bing in Portland 两堂交手 - 薛炳饮恨 11/30/13

秘密社会一览 12/12/13

The main problem for the historian is the multi-faceted nature of such organizations. Although all shared the political goal of overthrowing the Manchu dynasty that ruled China, some were more or less purely social groupings that focused on mutual aid and recreation for members. Others served administrative and judicial functions within the community, allocating business locations and cemetery sites, settling disputes, and enforcing the payment of debts. Still others engaged in criminal activities: protection rackets, extortion, and strong-arm methods for controlling such tolerated vices as gambling and prostitution. And, confusingly, a few such organizations were involved with all three sorts of activity at once: mutual help, administration, and crime.

Neither "Freemason" nor "secret society" is an accurate term. The many organizations that have sprung from China's historical Tiandihui 天地会 or Hung League/ Hongmen 洪门, and that have spread throughout the world with the Chinese Diaspora, are not connected with the Masonic movement in Europe nor, outside China at least, are they particularly secret. They were and are important, however. During the 19th and early 20th centuries they often dominated Chinese communities in Hong Kong, Southeast Asia, Australia, the Pacific Islands, and the Americas. They still play a major role in some of those places.

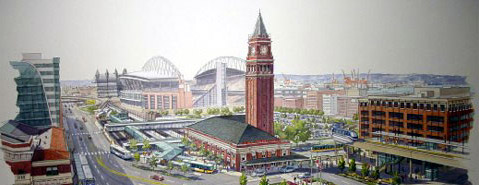

The Chee Kung Tang building in San Francisco, ca 1900. Wood block print from member's badge.

三藩市 致公堂 See below

We do not propose to delve deeply here into the criminal side of Chinese secret societies. It existed, was a source of embarrassment and sometimes fear to community members, and furnished sensational headlines for non-Chinese newspapers whose readers were fascinated by "tongs" and "tong wars." In some cases, violence and threatened violence formed a major part of a society's activity. In others, the only crime the society engaged in was gambling. Like European-American Masonic lodges in the midwestern U.S., the local headquarters of Chinese "Masons" often housed or sponsored illegal gambling operations. Unlike the Masonic halls of white Americans, those of Chinese immigrants were rarely immune to raids by police.

A Meeting Notice You Couldn't Refuse 见签岂有不到会

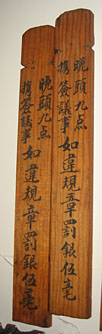

In 1970 when Vernon's Chinese Masonic Lodge, a branch of the Chee Kung Tong in British Columbia, was disbanded, part of the building's contents went to the Vernon Museum and Archives. Among them is a box of about 50 flat wooden sticks with the hexagonal end painted in red and writing on both sides (Figs 1-3).

On the front of each stick are three written characters “Chee Kung Tong”; on the lower part of the back are two written lines, stating “The agenda is set for eight o’clock. The Association has important business [to transact]. Brothers of the Hongmen [Association] will be fined $1 for being absent.” Each stick bears a different name and position in the Chee Kung Tong written on red paper, pasted on the top part of the back.

These sticks were primarily meeting notices for the Chee Kung Tong but may also have served as attendance records or name-tags during meetings. A rule laid down in 1876 by the Chinese Masonic Lodge in Virginia City, Montana, helps to explain the functions of the sticks:

“When the Lodge's [notification] sticks are issued for meeting discussions, [members] are obligated to reach their place and to handle business with justice without making excuses. Those who do not attend will be punished with 30 strokes of the cane.”

The wooden sticks in Vernon must have been used in a similar way as those in Montana, although the Vernon lodge was more lenient in terms of penalty.

The Chee Kung Tong lodge in Barkerville, British Columbia, seems to have used the same system. Six similar wooden sticks are on display at Barkerville's Chinese Museum. All except one have been crudely sawn off, perhaps to protect the identities of the individuals to whom the sticks were issued (Fig. 3).

Other examples that we have seen in the Pacific Northwest do not have "Chee Kung Tong" written on them but must have belonged to the CKT or a related organization. The example at Pom Yam House in Idaho City (Fig. 5) has a double-notched top. On one side it reads “Those not coming [to the meeting] upon seeing this stick will be fined 50 cents”. On the other side it reads “Meeting in the Public Hall.”

The three wooden sticks in the Beuk Aie temple collection in Lewiston, Idaho (Figs. 6 & 7), are almost certainly from the former Chee Kung Tong lodge of that city. Written in fine calligraphy, each reads, “Bring this stick to the meeting at 9 pm. The fine will be 50 cents if [you] violate the [attendance] rule.” On the lower part of the back is a pasted-on piece of red paper showing an individual’s name. That individual's position within the organization is written directly on the stick so that the name could be changed while the stick was recycled for the next generations of lodge members.

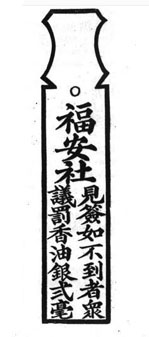

The concept and design of such notification sticks came from secret societies in China. A similar stick, of bamboo rather than wood, was seized by the Hong Kong police in the 1890s. Illustrated in William Stanton’s The Triad Society, Heaven and Earth Association, (1900), this stick closely resembles the examples from British Columbia and Idaho. It seems to have served the same

As far as the editors are aware, this is the first time that such meeting notice sticks have been identified in North America. Even though the exact wording of each group of sticks varies, the concepts behind all of them are consistent, illustrating a well-established and widely accepted administrative tradition.

Chairs of meetings for modern commercial and non-profit organizations are bound to admire the decisive approach of their Chee Kung Tong counterparts with regard to absentees. Some exasperated chairs might be satisfied with fines. Others, however, would probably prefer the Virginia City solution, penalizing their worst offenders with strokes of a cane.

The editors wish to thank the following for showing us the meeting notice sticks in their collections: Ron Candy, Director of the Vernon Museum, Ellen Vieth at the Lewis-Clark Center for Arts & History in Lewiston, Bill Quackenbush, Curator at Barkerville and Susan Hawkins of the U.S. Forest Service, who is the curator of Pon Yam House in Idaho City. A photograph of part of the Virginia City (MT) rules appears on page 286 of Christopher Merritt's Ph.D. dissertation, The Coming Man from Canton (University of Montana, 2010); we hope to get the Montana Historical Society's permission to reproduce it here.

Figs. 1-3 Meeting Notice Sticks from Vernon, BC 加拿大卑斯省费南市博物馆

Fig. 4 Meeting Notice Sticks from Barkerville BC 加拿大.卑斯省.巴卡维尔

Fig. 5 Meeting Notice Stick from Pon Yam House, Idaho City 爱达荷城 博物馆

Figs. 6-7 Meeting Notice Sticks from Lewiston, ID 爱德荷州.刘易斯顿市.大学博物馆

function. The inscription on It reads "Fu An [Cantonese: Fuh On] Society. If on sight of this notice [stick] the member does not attend the general discussion, he will be fined 20 cents as incense and [temple lamp] oil money" (Fig. 8). The Hong Kong example too has the name of the member and the meeting time written on red paper pasted on the back.

Figs. 8. Meeting Notice Stick from Hong Kong, 1900 香港

A Taboo Topic? 秘密社会可谈不可谈?

In the past, many Chinese-North American historians have ducked the issue of secret societies and their role in the history of Chinese in the United States and Canada. Some have avoided the subject altogether. Others have played it down, treating the secret societies as minor players or as criminal fringe groups that had no real influence. And still others have simply not understood enough of the special language, legends, and traditions of the ancient Heaven and Earth Society and its many offshoots to talk about them confidently.

We disagree. As in the case of opium, we think secret societies are a topic that has to be discussed. The existence of the secret societies should be grounds for pride as well as, sometimes, shame. Chinese North American sites and collections are filled with their artifacts. And the earlier history of Chinese on this continent is incomprehensible unless the secret societies, the so-called Chinese Freemasons, are taken into account.

The Non-Legendary History of the Chee Kung Tong 美洲致公堂早期历史

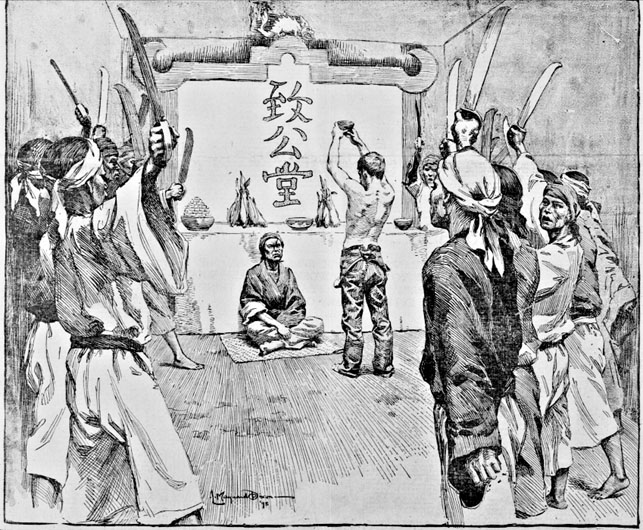

Initiation Ceremony, Chee Kung Tong, San Francisco, ca. 1900

New Data on the Chee Kung Tong

The recent appearance of searchable on-line versions of numerous historical newspapers and magazines, as well as the opening of relevant Chinese-language archives in Canada and the U.S., has made it possible for the first time to sketch a reasonably accurate history of the most important Chinese organization in the Americas during the 1880s and 1890s, the Chee Kung Tong. Most of the existing histories are either partisan, written by insiders concerned with presenting a glowingly positive image, or hostile, based on police information and presupposing that all Chinese secret societies, including the Chee Kung Tong, were nests of criminals. Click here for sources and details

=======================================

The Mother Society Puts on a New Face and Changes Her Name

从洪门到致公堂

It is clear that the society's name changed in the 1870-s and 1880s. The question is, why?

Our theory is that the leaders of the Hongmen felt it needed a new image. As also happened in Southeast Asia, the Hongmen of California soon began to spin off smaller secret societies. These often used Hongmen rituals and considered themselves to be, in part at least, its heirs. Unfortunately, certain of these derivative societies soon turned to crime. Like the modern Triad societies of East and Southeast Asia, which the American spin-offs closely resembled, they lived by extorting protection money from gambling houses, brothels, and legitimate businesses. They also fought fiercely for control of those revenue sources. Later, the white press would call these quasi-criminal organizations, "tongs," and their disputes over turf, "tong wars."

The bad reputation earned by such spin-offs must have influenced the Hongmen's decision to change its name, not once but twice. The first change was to "Chinese Masons." This had the effect of underlining an idea advanced by Western scholars, that the Hong Men might share a common origin with European-American Masons and that it was not only equally old but also, although secret, equally public-spirited and opposed to crime. Among the earliest provable dates for Chinese Masons in the English-language media were 1871 in Victoria, 1874 in Portland and Lewiston, 1878 in Sacramento, and 1880-1 in New York. By 1990, organizations calling themselves Chinese Masons or Freemasons existed in most North American Chinatowns

The Glory Days of the Chee Kung Tong 1890年代致公堂如日冲天

The 1890s saw the Chee Kung Tong at the peak of its power. Chinese texts and objects in museum collections point to the same conclusion as do historical photographs and English-language newspapers—the Chee Kung Tong then was by far the most important institution in most North American Chinatowns. In 1895, the San Francisco Chronicle stated that, contrary to what most Americans believed, the Chinese Six Companies [i.e., the Zhonghua Huiguan 中华会馆 or Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association] had “little or no authority” compared with the Chee Kung Tong.”

The Mother(s) of All Secret Societies 致公堂独步武林

The secret society that called itself the Chee Kung Tong 致公堂 (Pinyin: Zhigongtang, "Hall of Universal Justice"), was the dominant organization in New World Chinatowns in the late 19th century. Just about all Chinese secret societies were, in a way, descended from it.

Secret Society Secrets? 早期有关秘密社会的报道

The rituals of the organization known as the Hong Men, Tiandi Hui, Yixing Gongsi, etc., are considered by its members to be top secret. The editors are not privy to those secrets and, even if they were, would not reveal them here or elsewhere.

However, certain kinds of supposedly confidential information have long been in the public record. These include founding stories, regulations, and initiation ceremonies. Data on those are widely accessible (at least, to those with reasonably good Chinese educations), in Tiandi Hui manuals like the one described on this web page. The first Westerner to read and publish details of such manuals was one Dr. William Milne in 1826. Other non-Chinese writers on the subject include:

1826. William Milne, "Some Account of a Secret Association in China, Entitled the

1841. Lieutenant T. J. Newbold and Major-General F. W. Wilson, The Chinese Secret

Triad Society or the Tien-ti-huih," Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society,

1866. Gustave Schlegel Thian ti hwui:The Hung League, or Heaven-Earth-League,

Batavia (Jakarta).

1892. Frederic W. Masters, "Among the Highbinders," The Californian.

1900. William Stanton, The Triad Society or Heaven and Earth Association, Hong Kong.

1925. J. S. M. Ward & W. H. G. Stirling, The Hung Society, London.

1934. Shu Hirayama, Secret Societies in China, Shanghai. 平山周. 中國秘密社會史.

1960. W. P. Morgan, Triad Societies in Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

The full text of the relevant parts of the March 5, 1897, article in the San Francisco Chronicle may seen by clicking here. The translation was done by Frederic J. Masters, an Oakland missionary who, as noted elsewhere on this website, was a competent sinologist. Masters had to work quickly, however, and Yang himself, who seems to have been an unimaginative bureaucrat from a Chinese-Manchu "Banner" family in the northeastern province of Liaoning, may not have been able to write all that clearly in the first place. Hence, the Chronicle version has to be viewed with caution.

Chan Man Wai, Lee Hon You, that kind of people have been for a long time residing beyond the seas with no law before their eyes. Whatever rebellious footprints of the Chee Kung Tong were exposed they have constantly followed and practiced. When once Sun Man appeared they took rank as leaders.

Sun Man is the Cantonese reading of Dr. Sun's birth name, Sun Wen 孫文. Chan Man Wai and Lee Hon You (Cantonese: Lai Mon Hoy and Lee Cheuk Yon) were prominent men in San Francisco's Chinatown. The two of them, according to Yang Yu, "followed and practiced" the footprints of the Chee Kung Tong. Presumably this means they were members. But in which organization did they take rank as leaders after Sun Man appeared? And even if we understand Yang Yu to mean that Chan and Lee belonged to both organizations, the Chee Kung Tong and Dr. Sun's Heng Chung Hui, does this imply that there was a a formal connection between the two?

And yet the names "Chee Kung Tong" and "Chinese Masons" did not exist in those days. Chinese societies in China and Southeast Asia never used that name. As far as the editors can discover, neither did anyone else before the 1870s, whether in the Americas or the Pacific. The names first appeared two decades after the Hongmen is known to have reached California.

Click here for sources and details

=======================================

The organization itself was already old. Its parents were the cluster of independent but closely linked secret societies called the Hongmen 洪門 ("Hong Gate"), the Hongshuntang 洪顺堂, the Tiandihui 天地會 ("Heaven and Earth Society"), or the Yixinggongsi 义兴公司 ("Company for Promoting Integrity"). All members were sworn to overthrow the Manchu dynasty that ruled China, which meant they were fiercely persecuted by the government in Beijing. Such societies existed in China from the eighteenth century onward, had spread to Southeast Asia by the early nineteenth century, and came to the Americas with the first would-be Chinese gold miners in the mid-nineteenth century. As early as 1854, local English-language newspapers reported that the "Hung Society" was active in San Francisco.

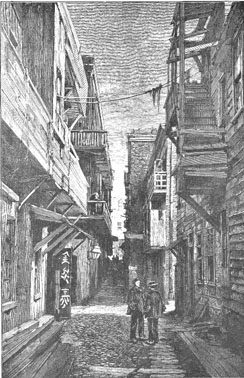

Alley with secret society buildings, San Francisco. Harpers 1886

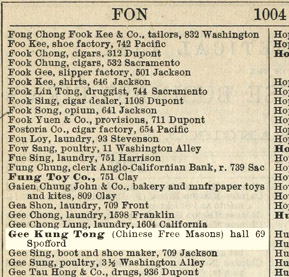

The second change was to "Chee Kung Tong". This took place in the early 1880s. The first definite mention of an organization with that name (in San Francisco) is dated to 1880. In 1882, a reporter in Los Angeles described a San Francisco secret society called the Chee Kung Tong, stating that it had a temple and membership certificates written on linen or silk. In the same year, two San Francisco newspapers reported the funeral of the "Grand Master" of the Chinese Freemasons, also called Chee Tong or Ghee Kung Tong.. In Barkerville, British Columbia, a photocopied Chinese-language text from Quesnelle Forks, currently on view in the site museum and listing regulations issued by the Hung Shun Tong 洪顺堂 uses "Chee Kung Tong" twice as an alternate name. The text bears a cyclical date equivalent to 1882.

By the late 1880s, the Chee Kung Tong claimed to have branches in 390 places in North and South America. A least some branches seem to have preferred the older name, continuing to call themselves only Chinese Masons, Hongmen, or Yee Hing Uey (Pinyin: Yixinghui) until the 1890s or, in the case of New York, even later. The English-language press first noticed the Chee Kung Tong in Victoria in 1888, in Indianapolis in 1890, in Chicago in 1891, in Sacramento in 1892, in Pittsburgh in 1895, and--finally--in New York in 1901.

Click here for sources, details, and references

Chee Kung Tong Building, Barkerville, BC

加拿大.卑斯省.巴卡维尔

The organization was now running into problems, however. One was the fact that its San Francisco headquarters had become involved in a violent struggle with a closely related society spun off in the 1880s, the Bing Kung Tong 秉公堂. Unlike many derivative “highbinder societies” or "fighting tongs," regarded, by whites at least, as associations of criminals, the Bing Kung Tong had a relatively high status. It laid claim to the title "Chinese Masons," behaved like the Chee Kung Tong's equal, and may indeed have seen itself as the true heir to the traditions of the Hongmen and the Tiandihui. Stung by the aggressive behavior of its rival, and perhaps by its pretensions as well, the Chee Kung Tong hired fighting men like those employed by the highbinder societies, and sank into a vicious tit-for-tat feud with the Bing Kung Tong. As a result, both groups of Chinese Masons were seen by many as highbinders themselves.

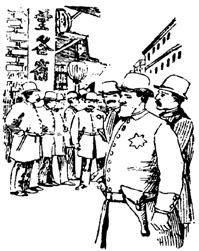

A second problem was the now-active hostility of the Chinese government, as represented by the consulate-general in San Francisco and the embassy in Washington. The consulate was behind a massive police raid on the Chee Kung Tong's San Francisco headquarters in 1891, a new “vigilante” organization meant to control the secret societies of San Francisco in 1893, the capture by the San Francisco police of secret society documents in 1894, and the destruction of several secret society headquarters in 1896. The Chinese government had previously shown little interest in the presence of the Chee Kung Tong in far-off California. Presumably now it was sensing increased danger from the old anti-Imperial ideology of the Hong Men. In 1897, a leaked Chinese ambassador's memo showed that the Chinese government planned to take strong measures against a suspected alliance between the leaders of the "villainous and heretical" Chee Kung Tong and Sun Man (Sun Yat-Sen or Sun Zhongshan), the future leader of the 1911 revolution.

The danger of a Manchu crackdown had receded by 1900, due partly to the arrival in 1897 of a more statesmanlike (and perhaps more sympathetic) ambassador, the remarkable Wu Tingfang, and partly to the fact that Chinese officials in Beijing were distracted by the Boxer Rebellion. The alliance with Sun Yat-sen's movement would gain strength, and this in turn would transform the Chee Kung Tong once again. By the time the Manchus were overthrown in 1911, the Hongmen-Tiandihui in Asia and the Chee Kung Tong in the Americas had moved up from the underground. It/they would play a significant role in Chinese politics in the 20th century.

Click here for sources and details

Chee Kung Tong headquarters in San Francisco just before the 1891 raid

San Francisco police during the 1891 secret society raid

Highbinder gunman, 1900s

Sun Yat-Sen and the Chee Kung Tong: could they have been formally linked as early as 1896?

孙中山与致公堂早在1896 年结缘旧金山?

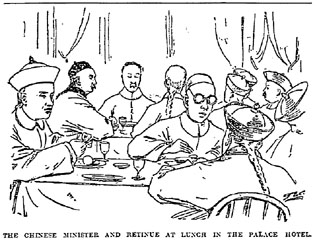

The ambassador's memo mentioned above (in the previous article), sent by Yang Yu (pinyin: Yang Ru) 驻美公使杨儒, the Chinese minister (i.e., ambassador) in Washington, D.C., to his superiors in China, is important for what it reveals about official Chinese information regarding supposed ties between the Chee Kung Tong and Sun Yat-sen (pinyin: Sun Yixian) 孫逸仙, now usually known as Sun Zhongshan 孫中山. Most historians agree that Dr. Sun joined the Chee Kung Tong in Honolulu in 1904, and that the society's support played an important role in the success of his revolutionary activities. And yet here is a possible connection between the society and Dr.Sun eight years earlier, in 1896. Could it be true?

Sun Yat-Sen in 1896, in London

Sun Yat-sen founds the Xingzhonghui in Hawaii in 1894

Sun Yat-sen and Wong Sam Duck (pinyin: Huang Sande) 黄三德, president of San Francisco's Chee Kung Tong, with supporters in Chicago, 1904

The editors think it may hint at but does not prove that such a connection existed. They think the most likely explanation is that the connection was individual rather than organizational. If certain Chee Kung Tong members like Chan Man Wai and Lee Hon You had been interested in Sun's ideas and perhaps become his supporters, that would make sense of Yang Yu's accusation without having to assume that the whole Chee Kung Tong could have been converted to Sun's cause during the few weeks that he was in San Francisco during late June and early July, 1896.

The article does show that conservatives in the imperial government, of which Yang Yu was one, were deeply concerned about the subversive activities of the Chee Kung Tong (pinyin: Zhigongtang) 致公堂 and of Sun Yat-sen's "Heng Chung-China Reform Association" (pinyin: Xingzhonghui) 興中會, formed by Sun in Hawaii in 1894, and that they suspected there was a connection between the two organizations.

Was there a connection? The Chronicle's version of Yang Yu's letter is ambiguous. The key sentences are as follows

Yang Yu (with black cap) in San Francisco in 1893

Chinatown police, 1890s

版权 Copyright is free for non-profit use: : click here for more information

Such proofs of membership are scarce in modern museums and archives, but others do exist. One example is shown in the preceding section. Far from belonging to a criminal, it was issued by Portland's Chee Kung Tong to Doctor Ing Hay, an eminently respectable Oregonian.

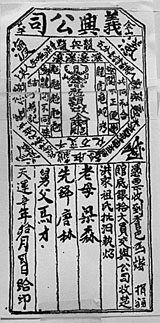

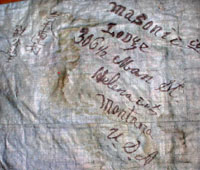

Two other such proofs are shown above. One is from the University of British Columbia Archives (Chinese Canadian Research Collection, folder 10-11, no. 2). Issued in 1906 by the Chee Kung Tong in Victoria, it bears the English-language stamps of the organization and its Tai-lo [leader]. The other is from William Stanton's The Triad Society 1900, p 80, as reprinted in Xiu Yishan's Historical Data on Recent Secret Societies (Shanghai Wenyi Chubanshe, 1991).

The text on all three badges begins with the term Yee Hing Kong Si (Pinyin: Yixing Gongsi), which was an alternative name for the Chee Kung Tong/ Hongmen. All three bear Tianyun dates of the kind described above..

The fourth badge shown here is from Schlegel's classic Thian ti hwui, published in 1866. It was one of nine, some printed on silk and others on paper, seized by Dutch colonial police in Indonesia during the 1860s. Schlegel regarded this one as a "Grand Diploma," carried only by high-ranking members of the organization

High-ranking membership badge from Indonesia, 1860s,from Schlegel 1866 p 28

Speculations about the connection between the Tiandihui/ Hongmen/ Chee Kung Tong and the Freemasions of Europe and North America go back to the early 19th century. Most historians doubt that the two groups of organizations share a common ancestor or that they had any other direct connection in. the past. And yet the similarities between the two are so compelling--in rituals, in social function, and even in former revolutionary sympathies (less direct in the case of Euro-American lodges)--that Chinese and western Masons have long sought to build bridges to each other.

A recent example of this is the decision by the Grand Lodge of the Montana Freemasons to include in their museum a handsome altar cloth from the Chee Kung Tong building in Helena. The back of the cloth bears Chinese inscriptions reading "Chee Kung Tong" and "Helena"in Chinese and Masonic Lodge, 305 1/2 Main St., Helena, Montana, U.S.A." in English. The front of the cloth shows a group of lions in couched gold thread on a red background. It is of good quality and must have been imported from China in about 1900.

The Chee Kung Tong and American Masons in Helena, Montana

致公堂与美国的兄弟会 -蒙大拿州喜连拿市一例

How was the cloth used? Probably to cover the front of an altar table. Similar cloths that served as banners for processions are displayed in the Won Lim temple in Weaverville, Calfornia, formerly also a Chee Kung Tong institution. However, the Weaverville examples, although they too have gold couching and an envelope-like upper flap, are narrower than the Helena cloth and have silken fringes.

Chinese Masonic Lodge, Helena, 1899. In a later image, the characters over the door can be read: "Chee Kung Tong"

Altar cloth from the Chinese Masonic Lodge/ Chee Kung Tong in Helena 喜连拿市 致公堂文物

Procession banners in the Won Lim temple, Weaverville 加州云林庙文物

Note: The cloth was brought to the editors' attention by Reid Gardiner, Grand Secretary and Curator, Grand Lodge, Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Montana, Helena, MT. We are grateful to him for the information as well as for sharing his knowledge of the history of Masonry. He tells us that his organization will be putting the hanging on exhibit in the Montana Masonic Museum.

If this is what Yang Yu meant, it would not be a surprise. Sun had been on the edge of, if not fully inside, Chinese secret societies since his student days in the late 1880s. While a medical student, he became friends with several reputed Hong Men members (see http://www.lilicat.com/sun_yatsen.php), and his own anti-Manchu sentiments meshed nicely with the ideology of the Hong Men/ Tiandihui and its affiliates. However, Yang Yu's letter does offer proof that in 1896 Chinese officials believed that Sun had already joined the North American/Hawaiian version of the Hong Men, Chee Kung Tong.

Partial confirmation of an early connection between Dr. Sun and secret societies appeared in an article in Britain's Blackwood's Magazine, reprinted by the Eclectic Magazine in February, 1897. Titled "Secret Societies in China, Sun Wen's Arrest," the article states that "if the agents of the [Chinese] Government are to be believed, Sun is not only an active member of the 'White Lily' Association, but is a prominent member of that very revolutionary body." The term "White Lily," presumably identical with the earlier White Lotus Society, may have been out of date by then. However, one does not doubt that a Chinese official, perhaps in London's Chinese Legation, told a Blackwood's contact that Dr. Sun belonged to an organization which, like the White Lotus, was dedicated to the overthrow of the imperial government.

金山西北角 - 华裔研究中心

This page was last updated: August 30, 2018

The Mysterious Disappearance of Portland's and Seattle's Chee Kung Tong 钵崙.西雅图.两地致公堂无故隐退

It is a vexing, if infrequently asked, question. Why is there no trace of the Chee Kung Tong in Seattle or Portland, even though that organization was once dominatingly powerful in the Chinatowns of those cities? Could it have vanished so utterly, when abundant traces of the CKT survive in most other North American Chinese communities?

Now we can suggest an answer. It was replaced, perhaps with minimal friction, by the Bing Kung Tong 秉公堂 (BKT).

The attached chronology of the CKT and BKT in the Pacific Northwest documents this changeover. The CKT was in Portland by 1882. The BKT did not appear there until 1914. For now, the chronology has to be based on data from on-line historical English-language newspapers and a bilingual business directory. We have not sifted through surviving issues of the relevant Chinese-language newspapers yet. However, the English-language newspapers at that period knew a lot about American Chinese organizations, apparently because representatives of those organizations talked freely to white Americans in an attempt to win local media, courts, and police over to their sides.

The CKT had once dominated many Chinatowns. Even as late as 1910, the Oregonian (1910-03-20 p 4) could state it was still “more puissant" than the Chinese consulate. The newspaper might have added that the CKT was also more puissant than the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association when disputes needed settling, even though the CCBA had already been present in Portland and Seattle for almost twenty years

In the 19th century, the CKT in most parts of the Pacific Northwest had provided many of the social services that would later be the responsibility of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, the CCBA. The CKT could do this because it was rich through member’s dues and gambling operations, which neither Chinese nor whites regarded as a serious crime. While other secret societies formerly engaged in such serious crimes as extorting protection money from businesses and levying "taxes" on prostitutes, there is no evidence that the CKT did the same. Moreover, except for a brief spate of violence in San Francisco and Sacramento during the early 1890s (see "1890" and "1892" after clicking here), it seems that the CKT refused to engage in tong wars.

But in spite of all this, at the end of 1912, the CKT disappeared from the Chinatowns of both Seattle and Portland, never to reappear. It continues to exist in California (where it survives together with the BKT, both organizations calling themselves Chinese Masons) and in much of the rest of the U.S., Canada, and various other countries.

Possible evidence of a low-friction transition comes from Portland, where the BKT's present shrine bears evidence of having been made for another organization, probably the CKT. The evidence takes the form of a date on the handsomely gilded woodwork that surrounds the niche of its present shrine: Guangxu 30, equivalent to AD 1901. The fact that the date is carved in relief and covered with gilt lacquer shows that it cannot have been added afterward. Because no organization calling itself the BKT existed in Portland at that time, and because the wooden parts of shrines, unlike bells, seem rarely to have been transferred from one organization's building to another's, it seems reasonable to think that the shrine was originally made for the CKT and inherited, perhaps with the building itself, by the BKT. As the attached chronology indicates, the transition must have been rapid.

So what happened in Seattle and Portland? The attached chronology implies that the CKT was replaced by, first, the Bow Leong Tong and, shortly afterward, by the Bing Kung Tong.

Was the takeover friendly or hostile? Did members willingly change switch over from the CKT to the BLT/BKT? We do not know. However, it is worth noting that by 1917, the BKT was laying claim to the anti-Manchu revolutionary credentials of the CKT (see "1917" in the Chronology section) as well as the title "Chinese Masons." In Victoria and Vancouver, a similar changeover occurred in the 1910s, when the old CKT was largely replaced by the Dart Coon Club. That particular transition took longer and seems not to have been overly friendly, but it is possible that the change from CKT to BKT occurred with minimal friction.

Bing Kung Tong building, Seattle. 西雅图秉公堂

Bing Kung Tong

Portland. 钵崙秉公堂

Chee Kung Tong building, Portland, 1890s

(UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED ALL DATA ON THIS PAGE COMES FROM THE EDITORS' OWN RESEARCH ON PRIMARY SOURCES & ARTIFACTS)

Earliest known use of "Chee Kung Tong" name, in San Francisco directory compiled in 1880. Click to enlarge.

The Secret Society Murder of Seid Bing 两堂交手 - 薛炳饮恨 [Note 1a]

The editors have avoided describing details of the secret society violence—the so-called “tong wars” — that plagued West Coast Chinese communities from the late 1880s onward. We do not wish to minimize the subject, however. Many Chinese were killed by other Chinese during the tong wars, and many non-tong members lived in a state of more or less constant fear because of those wars.

In the interests of bringing the subject into the open, we will present a few cases of special significance to the overall history of Chinese America.

One such case is that of Seid Bing, a Bow Leong Tong 保良堂 member who became the victim of a carefully planned murder by the Hop Sing Tong 合胜堂 [Note 1b]. The case became famous because one of the supposed conspirators was a female Hop Sing member, the beautiful Oi Sen 爱仙.

A fuller version of Oi Sen’s story appears on the Women page of this website. She was the one who, on December 20, 1911, allowed her Hop Sing fellows to ambush her lover of four years, Seid Bing, in her second-floor apartment on 4th Street in Portland. Seid was a cannery foreman and minor labor contractor in Astoria, a playboy with at least one white girlfriend, and a nephew of the powerful Portland merchant, Seid Back. He may also have

There was no mystery about whose body it was. It had several letters in a coat pocket. Two were addressed to Seid Bing in Astoria, from Bertha Martin of Empire City, Oregon, and Florence Couland of Astoria. The first was a love letter. The victim had evidently been a ladies’ man. .

There was also no mystery about where the trunk came from. A baggage handler in Portland remembered the sender, said to be a small and beautiful Chinese girl, who had asked him to pick up the trunk at her apartment. Neighbors identified her as Oi Sen, a well-known courtesan. A region-wide search for her ensued, spurred by a $500 reward offered ostensibly by the police but actually by Seid Back and the Bow Leong Tong. From a journalist’s standpoint, the case had everything: beauty, money, organized crime, an exotic setting, and a grisly method of body disposal. Naturally enough, it became headline news all over western North America.

Oi Sen, well-dressed, good-looking, and self-confident, was not inconspicuous. With so much publicity, she was found within a few days, in Billings, Montana. She waived extradition and was back in Portland by mid-February,

Most of what is known about the murder comes from her courtroom testimony and from an unpublished Immigration Bureau interview with her conducted a year later [Note 3a]. The killers, she said, were Law (the newspapers called him, incorrectly, Lew) Soon 罗旋, and Wong Si Sam 黄世森, Both, like herself, were members of the Hop Sing Tong. Their society had a long-standing feud with the Bow Leong Tong, to which Seid Bing belonged. The feud had begun in Portland thirty years previously, when no fewer than six Hop Sings and Bow Leongs had been killed in a single day [Note 2b]. Seid Back, Seid Bing’s uncle, indignantly dismissed tong rivalry as a motive, stating in an interview that the Bow Leong “has been classed as a Seid family society. This is absolutely false. While one or two of the Seid family belong to the society, the majority does not” [Note 2c]. Nobody believed him, however. Almost everyone in Portland, white and Chinese alike, knew that the local Bow Leong was under Seid family control and that the murder was another skirmish in a long-standing secret society feud.

One of the killers, Wong Si Sam was a cook on the Columbia river steamer Bailey Gatzert, now the name of a Seattle school attended by several generations of Chinese Americans. He was a close enough friend of Oi Sen to have helped her escape from Portland, hiding her in his cook’s cabin until the boat reached the Dalles further up the Columbia, where she caught a train to Montana.

The Oregonian claimed that Law Soon was the president of the Hop Sing Tong in San Francisco. Oi Sen, who knew him and his mistress or wife, a prostitute named Wah Tsoy, quite well, said that at the time of the murder he was the local head of the Hop Sing. How he earned a living is not clear. One newspaper called him a San Francisco saloon keeper. Also, Oi Sen said, Wah Tsoy regularly turned her earnings from prostitution over to him.[Note 3a]

On April 24, Wong Si Sam was found guilty of second degree murder and given a life sentence. Law Soon, indicted for first degree murder, was due to come to trial within a week or so [Note 3b]. However, a series of unexplained delays ensued. These delays continued through the fall. Then, in December of the same year, the state Supreme Court found, surprisingly, that the circuit judge had committed “an alleged error” and allowed Wong to plead guilty to the lesser crime of manslaughter. His sentence was reduced to one to fifteen years and a fine of one hundred dollars [Note 4].

An important aspect of the Seid Bing murder case is that it reveals unexpectedly close relations between white law enforcement and Chinese secret societies. The Hop Sing Tong seems to have been able to influence an assistant district attorney and even justices of the Oregon Supreme Court, not to mention the governor of California as well as the police who were paid to look the other way in gambling cases and when killings occurred like the one at the Non Kin Restaurant. The Bow Leong and/or the Seid clan was almost a part of the Portland police department. Seid Back’s son, Seid Back Junior 薛天眷, accompanied Portland’s police chief when he went to Billings to bring back Oi Sen. Seid Wing became “an active assistant to the authorities.” In 1913, for instance, he walked into the District Attorney’s office and confronted a suspect there, identifying him by a cloth badge as a Hop Sing gunman from San Francisco. In a 1912 interview with an Oregonian reporter, Seid Back Senior implied strongly that his clan could control access to the city prison: “To show our fairness, we allowed . . . the Hop Sing Tong to visit the woman (Oi Sen) in the jail and to ask her questions . . . while we could have refused to ler her society’s representatives to see her, we made no objections to letting them enter the jail and ask them all the questions they wanted.” [Note 5c]

The murder was not discovered until January 24, 1912, when a Railway Express employee at King Street Station in Seattle noticed a foul smell coming from a pile of stored baggage. He followed the smell to a trunk at the bottom of the pile. Opening it, he found the dismembered body of a Chinese male, still almost fully clothed. It had been expertly cut up, heavily salted, wrapped in paper, and packed in the trunk, surrounded with sawdust. The trunk had then been shipped by train from Portland to Seattle, where no one planned to pick it up.

Seid Back, ca. 1915. 薛栢

Wong Si Sam & Oi Sen, ca. 1912. 黄世森. 爱仙

King Street Station in modern Seattle. In 1912, Seattle's Chinatown had already moved to its present location just to the left of this picture.

The Bailey Gatzert on the Columbia, 1910, from Wikipedia, Wong Si Sam was already the steamboat's cook when this picture was made.

This ruling, also surprisingly, caused Portland’s Deputy District Attorney, Fitzgerald, to change his mind about trying Law Soon. Now, he announced, convicting Law Soon would be impossible, and anyway, the trial would cost too much because they would have to bring witnesses all the way from from Seattle. Hence, the charge of first degree murder had to be dropped. The same was true of other possible charges. Clearly, the fix was in.

Law Soon went free and within a few months had returned to his old ways. In March 1913 he stood in the door of the Non Kin Restaurant in Portland, watching two of his Hop Sing “cohorts” as they gunned down the second Bow Leong slated for death that evening. The shooting was witnessed by half a dozen Chinese, who asserted that Law Soon had been directing the cohorts [Note 5a]. None of these cared to say that in a courtroom setting, however. Several months later, Law Soon was captured at the Hop Sing headquarters in San Jose, CA, and charged with masterminding the murders of the two Bow Leong members. However, once again he was never tried and convicted. This time he was aided by a state governor, California's. Hiram Johnson, who refused to sign Law's extradition papers [Note 5b]. .

Hop Sing Tong Building, San

Francisco, 1910

Hop Sing Tong Building, Portland, 2010

As pointed out on another website, in Chicago relations between Chinatown leaders and local white politicians, as well as the violence-prone political clubs they controlled, stayed peaceful for more than a hundred years. The explanation, Chicago being Chicago, was Chinese generosity with "boodle"--what we now call campaign contributions. A similar situation may have existed in early Portland. This is not to say that the Portland government’s historic willingness to protect Chinese was solely due to bribery. But boodle may well have played a part.

For instance, in Seattle. The bribes almost certainly came through merchant houses or secret societies, not directly from the prostitutes and gamblers themselves. [Note 6]

been native-born and hence an American citizen. A cannery employee named Bing Seid was allowed to register as a voter in Astoria in 1908 [Note 2a].

Note 1a. Names in Chinese have been taken from articles on the Seid Bing murder in January and February 1912 issues of the Chinese-language

San Francisco newspaper, Chung Sai Yat Pao 中西日報

Note 1. For details of the developing Seid Bing murder story, see Oregonian 1912-01-25, -01-26, -02-03, -02-04, -02-08, -02-10; San Francisco Call

1912-01-26.

Note 2a. Oregonian 1908-02-29, p 9

Note 2b. Sacramento Daily Union 1888-12-02; Hawaiian Gazette 1889-01-08.

Note 3a. NARA-Seattle, Chinese Exclusion Files, #4441 (Chun Yook)

Note 3b. For the trial, see Oregonian 1912-04-18, -04-24, -04-14; Tacoma Times 1912-04-24.

Note 4. For the resentencing of Wong Si Sam and the dropping of charges against Law Soon, see Oregonian 1912-19-05, -12-10, -12-18.

Note 5a. Oregonian 1913-03-17, -03-19.

Note 5b. Oregonian 1913-07-20, 1915-01-24.

Note 5c. Oregonian 1912-02-08

Note 6. Astorian 1885-07-14

New Dates for the Origins of North American Secret Societies美洲西岸早期秘密社会一览

The editors have worked out a new chronology of Chinese secret societies in California and the Pacific Northwest. We believe the dates in it to be more accurate than those in any previous publication. The chronology is based on recently available on-line digital versions of the principal West Coast newspapers of the 19th century, supplemented by data from early epigraphic and archival sources. Only primary sources have been used, while secondary sources from the 20th and 21st centuries have been disregarded. Though abundant, many such derivative sources suffer from ignorance, sensationalism, and prejudice. Even respectable academic studies have felt obliged either to accept dubious facts for lack of anything else or to suppress details out of concern for political correctness. We think that the appearance of so many digitized 19th century publications has changed the situation. Now, many more facts are accessible and one can begin to see how the secret societies, in spite of their repeated descent into violence and crime, played a pervasive and often positive role in early Chinese North American communities.

The full chronology may be viewed by clicking here. It will be seen that secret associations calling themselves Hong Men or Hong Shun and identified as Triad Societies, were noticed by the white press in San Francisco as early as 1854 and that these, as suggested above, morphed into Chinese Masons in the early 1870s (but see the following article) and the Chee Kung Tong in the early 1880s.

Certain other societies, most or all of which used many of the rituals and organizational concepts of the Hong Men, appeared surprisingly early. The Bing Kung Tong, which claims to have separated from the Chee Kung Tong in 1874, cannot on independent evidence be shown to have existed before 1889, in Los Angeles rather than San Francisco. However, the BKT's historic rival, the Hop Sing Tong, is mentioned repeatedly by various newspapers as being active in Virginia City, Nevada, in the mid-1870s; it does not appear in San Francisco until 1881 and in Portland until 1888.

Other societies that appear first in places other than San Francisco are the Hip Sing Tong and the so-called Chinese Masons, almost certainly the old Hong Shun Tong/Hong Men and the future Chee Kung Tong. The Hip Sing was in Victoria in 1884, a year before it appeared in San Francisco. The term "Chinese Masons," on the other hand, is much earlier in the Northwest than in San Francisco. It was used in Weaverville by 1864, in Victoria by 1871 and in Portland and Lewiston (Idaho) by 1874, whereas San Francisco newspapers seem not to have known the term until 1882.

Exactly what this means is not clear. But at least it appears that, as far as secret societies ago, San Francisco was not always the dog and other Chinatowns the tail.

On Barkerville CKT dates. The three historians who first published the Quesnelle Forks text, Lyman, Wilmott and Ho (1964), state that the text gives a 1876 date for the founding of the British Columbia lodge of the society and that the Quesnelle Forks chapter was founded six years later. Basing their opinion on "other sources," they go on to say that "a chapter of the Chih-Kung T'ang [= Chee Kung Tong] was founded at Barkerville in 1862." But they do not name the other sources, and no one else seems to have known about them either. In view of this, not to mention the fact that the Lyman date for Barkerville's CKT, 1862, is (a) earlier than Barkerville's Chinatown, which according to Chen (2001) did not exist until late 1863 or 1864 and (b) eighteen years older than any other use of the CKT name, we may conclude that the suggestion of Lyman and his co-authors need not be taken seriously. The same is true of a 1864 date given by David T. H. Lee in his Chinese-language Overseas Chinese History in Canada (1967: p 233), which he says is based on "a legend among early Chinese." Although various popular writer have accepted this legend as fact, Chen (2001: pp 187 & 197) is skeptical and so are we, the editors. Lee's 1864 date appears to have no basis in fact.

Two account books preserved in the Barkerville Archives agree with the Quesnelle Forks text in showing that an unnamed secret society, presumably the Hong Shun Tong, existed in Barkerville in 1876. A third account book, dated to 1880, bears the names of the Hong Shun Tong and, as a synonym, the Yee Hing Society. It lists donations to a fund for building a new lodge

Account books of a secret society in the Barkerville Archives: the top two, which do not name the society, are dated 1876.

The one on the lower left bears a 1880 date and names of both the Hong Shun and the Yee Hing Societies. The one on the

lower right is undated and belonged to the Hong Shun Tong.

The diagonal bars in this photo will be removed when

the Archives' permission to publish is received.

On Victoria CKT Dates. The historian David Chuenyan Lai (Chinese Community Leadership, 2010, p 44) refers to an unpublished manuscript in the archives of the Chinese Freemasons (= Dart Coon Club?), Victoria, by Cao Jianwu, 1930, "The History of the Hungmen's Participation in the 1911 Revolution." In the manuscript, Cao apparently states that Victoria's Chee Kung Tong was founded in 1876 by Hongmen members from Seattle, including Lim Lihuang, Zhao Xi, and Ye Huibo (a.k.a. Yip On, later to be president of the Chinese Empire Reform Association). Considering that there already were Chinese Masons (presumably Hong Men/ Hong Shun Tong) in Victoria in 1871 (British Colonist 1871-05-02), an 1876 date is no surprise, although the organization may not have been called Chee Kung Tong at that date. More surprising is (1) that the founders came from Seattle, which had a much smaller and less influential Chinese population in those days, and (2) that Charley Yip On, later a central figure in Canada's Chinese mercantile elite, was one of them. The editors hope to see the manuscript themselves and see whether Cao recorded further details.

At present, both the Chee Kung Tong and Bing Kung Tong call themselves Chinese Msons, use the Masonic square-and-compass symbol, and prize their right to use that name. But the first known occurrance of the use of that term is older than either the CKT or the BKT [Note 1] and now seems to have taken place in remote Weaverville, California. An article in the Trinity Journal, dated December 17, 1864, reads as follows:

Last Sunday night the Chinese Mssons (that's what they call themselves) had a meeting at the Theater. It was public, and not a few whites went to see the strange doings of the Celestials. They drank China brandy and tea, ate roast hog, smoked opium and seemed to enjoy themselves higely. One of the "big men" informed us that is is a very important institution -- takes care of all sick Chinamen and fee the hungry ones [Note 1].

Note 1. Bennet Bronson and Chuimei Ho, 2015, Coming Home in Giold Brocade: Chinese in Early Northwest America, pp 126-130. See also the Chronology article on this websive.

Note 2. Transcribed by Rita Hancock, 1990s, “Chinese History in Trinity Journal.” Available at Weaverville Museum Research Center 1990s

Note 3. British Colonist 1871-05-02)

Note 4. Oregonian 1874-03-02

The Journal records two other meetings of the Chinese Masons before 1870, in January 23 and December 18, 1869. Both meetings, though held in a local theater, were private. In the 1870s the Masons acquired their own building close to Weaverville's Won Lim Temple. The temple had a close connection with the Hong Shun Tong, attested by several inscriptions with 1874 dates. Presumably it was the Hong Shun Tong's members who began to call themselves Masons.

As the preceding article shows, until now the editors believed that "Chinese Masons" was not used by any Chinese organization until the term appeared in Victoria in 1871 [Note 2] and in Portland in 1874 [Note 3], But now we find it in Weaverville, six years before Victoria and sixeen years before San Francisco! How is this to be explained? Could a small town in the Trinity Mountains possibly be the source of such a major innovation?

True, the chronology of secret societies shown elsewhere on this website is based on publicly available sources, and in the 1860s-70s much was happening in Chinese secret societies that the public knew nothing about. But so early, in such a small, far-off place? We cannot explain it.

One of the Hong Shun Tong inscriptions in the Won Lim Temple is discussed elsewhere on this web page. A future section will describe the temple's other Hong Shun Tong inscriptions.

A New Date for the Earliest Chinese Masons