Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee (CINARC)

This page was last updated: August 30, 2018

金山西北角 - 华裔研究中心

(UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED ALL DATA ON THIS PAGE COMES FROM THE EDITORS' OWN RESEARCH ON PRIMARY SOURCES & ARTIFACTS)

Chinese in Cities of the Pacific Northwest

This page sketches the Chinese histories of Northwestern cities, with cross-links to other parts of the CINARC website that have relevant data.

1870s-1905 Chin Gee Ghee 陈宜禧 (railroad contractor/ merchant/ visionary capitalist) is a dominant figure in Seattle’s Chinese community. For a list of articles about him on this website. click here

1880-1890 Chin Gee Hee’s herbal remedies for contract laborers in Seattle. 西雅图早期华侨陈宜禧商业档案中的医方

1886 Most Chinese are driven out of Seattle by white mobs. 西雅图唐人街

1887 The first recorded Chinese restaurant in Seattle. Such restaurants would not become common there until chop suey was introduced in the mid-1900s, and by then Chinese restaurateurs faced overwhelming Japanese competition 西北角早期杂碎餐馆

1888, 1899, 1902, 1904 Some of the many cases of opium being smuggled (mostly by whites) into or through Seattle 走私個案

1891-1905 The Chee Kung Tong secret society is recorded as being active in Seattle.

1892 Seattle's Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association organizes the exhumation and repatriation of deceased Chinese 西雅图也参与执运工程

1892 A new date for the founding of Seattle’s CCBA/ CWBA (Chong Wa Benevolent Association) 西雅图中华会 馆何时成立

1900-1933 Goon Dip (contractor/ mine owner/ merchant /diplomat) moves from Portland to Seattle. 阮洽生平事迹 For a list of articles about him on this website. click here

1903 The Chinese Empire Reform Association (Baohuanghui) is incorporated in Seattle, having been founded a few years previously 舍路保皇会注册文件

1906 Prince Tsai Tseh and the Imperial Commission come to Seattle 晚清出洋考察大臣: 镇国公戴泽抵西雅图

1906 In Seattle, the coffin of Tom Gin How, a leader of the Chee Kung and Hip Sing Tongs is brought back to the city after his "burial."

1909 Seattle’s Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, 1909. 西雅图1909博览会

1909 Women who were not down-trodden: Dong Oy and Maggie Chin return to Seattle. 不倔不挠话曾爱

1913, 1917 The closely related secret societies, the Bow Leong Tong and the Bing Kung Tong, are first recorded in Seattle in these years.

1914 A visiting Chinese diplomat notes that Goon Dip is succeeding in protecting the 1,000-strong Chinese community of Seattle from poor treatment.

1915 Why do the CCBA buildings in San Francisco and Seattle bear the same dedicatory inscriptions? 对联情意结 - 三藩市与西雅图两地的中华会馆

1933 Goon Dip is buried in Lake View Cemetery, Seattle, having decided that America, not China, will be his final burial place 衣锦不还乡: 西雅图阮洽家族墓冢

Much more information must exist in contemporary newspapers, but the most important of those (notably, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, founded in1867) are not yet on-line and digitized. Until that is done, readers must depend on the scraps of information presented on this website and on compilations from secondary sources. One of the best such compilations is that of Doug Chin (Seattle’s International District, 2009, 2nd ed., pp 13-19).

The following articles on this website pertain to Chinese in Seattle.

SEATTLE

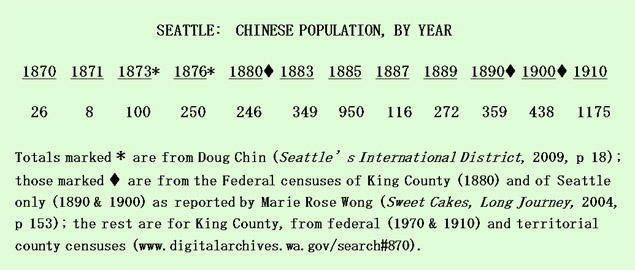

The Chinese population of Seattle crashed after the 1886 drivings-out and took about twenty years to recover, By that time, Chinese were a much smaller proportion of the population than before and had a less important role in the local economy. In those senses, 1885 represented a high point for Seattle's Chinese that would not be reached again.

It should be noted that these figures, like those for Chinese in other cities, probably represent serious undercounts. Many seasonal laborers would have been away at work sites on census day, which during the late 19th century was always June 1st. Numerous other Chinese would have been missed because they hid from the census-takers, fearing government mistreatment and/or deportation. Moreover, the various censuses were conducted solely by English-speaking enumerators with varying levels of training, motivation, and intelligence. For later decades, the totals should be adjusted upward to account for a slow increase in the American-born Chinese population, who in most censuses were not listed as "Chinese."

1880s-1890s Date of excavated Chinese site in Port Townsend where opium equipment, including pipe bowls and lamps, was found. For more on the finds, click here.

1883, 1884, 1890, 1891, 1894, 1895, 1904. Port Townsend serves as a base for smuggling illegal Chinese immigrants into the U.S.

1886 One Port Townsend Chinese is attacked and killed; otherwise, the city escapes the anti-Chinese violence that has broken out elsewhere in the region. http://www.cinarc.org/Violence.html#anchor_101

1893 Hattie Stratton, “a pretty smuggler” from Port Angeles is apprehended in Port Townsend.

1893 A “Great Smuggling Ring” running opium from Victoria to Port Townsend is uncovered.

1895 New high-speed revenue cutters are built in Port Townsend, to interdict the smuggling of :”opium and Chinamen” from Canada.

1895 Another white lady smuggler from Port Angeles is caught by Port Townsend customs officials.

1901-2 A new Chinese “detention house” for processing Chinese ship passengers inbound for Seattle, Tacoma, etc., is opened in downtown Port Townsend.

1906 Prince Tsai Tseh and a Chinese imperial delegation are greeted in Port Townsend by white officials and important Northwestern Chinese. One Port Townsend official, A. W. Bash, accompanies the Prince’s party onward to Chicago.

1906 Cheng Moy Lan, wife of an Idaho merchant, enters the country at Port Townsend. She may be one of the last Chinese immigrants to land at Port Townsend rather than Seattle.

1908 A front-page article in the Seattle Times details the danger of a Japanese attack on the forts at and near Port Townsend, the main naval defenses of Puget Sound.

PORT TOWNSEND

Chinese must have begun coming to Port Townsend in the 1860s, at about the same time they began settling in Victoria, a few hours away by sailboat. Before 1900, most Chinese immigrants to the northwestern states who came by sea entered through Port Townsend, and enough of them settled there for a modest-sized Chinatown to appear, sustained by trade between foreign countries, especially Canada, and the cities of Puget Sound.

Located at the east end of the strait that separates Canada from the U.S., Port Townsend with its strategic location and deepwater harbor became a major seaport, transshipping cargoes for much of the region. The rising power of the Northern Pacific and Great Northern railroads in the 1890s, with their own ships and loading terminals in Seattle and Tacoma, spelled the end for Port Townsend as a transshipment center. After that, it fell back to being an ordinary small city, sustained by minor manufacturing, military spending, and smuggling.

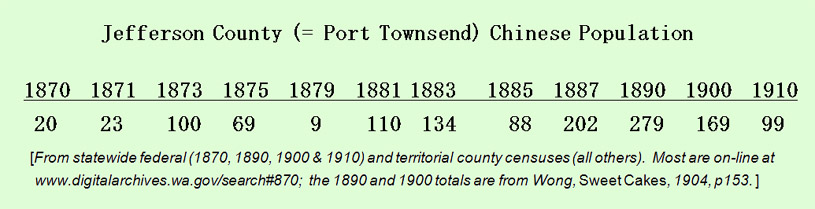

As with all early census data as applied to Chinese in the U.S., these totals cannot be trusted—too many Chinese had reason to hide from census takers, perhaps especially in a smuggling center like Port Townsend. A secondary source states that Port Townsend's Chinese population “reached its peak in 1890 with 453 people.” We do now know where this figure comes from but do not think it is impossible if illegal immigrants are counted in.

The good times for Chinese in Port Townsend lasted through the end of the 19th century. A generally tolerant attitude on the part of the white population meant less harassment. In 1885-6, some Chinese even fled from Seattle and Tacoma to Port Townsend and were protected there. A few regular Chinese residents engaged in service industries aimed at local whites, and some worked on farms and market gardens near the city and on Whidbey island. Most, however, seem to have made a living through trade, receiving goods from Asia and Canada and sending them onward to Chinese wholesale and retail merchants in Seattle, Tacoma, and even Portland. In keeping with well-established Port Townsend tradition, many such goods were contraband, brought over from Canada or overseas places without paying customs duty.

Opium, legal but heavily taxed when crossing the border, was a major item of contraband aimed at Chinese consumers. So too were such essential Chinese goods as silks, tobacco, and distilled spirits from Guangdong. And one should not forget undocumented Chinese individuals, who often crossed over from Canada to or near Port Townsend. In all such cases, the smugglers themselves were whites, while those receiving the smuggled goods or individuals were Chinese merchants based in Port Townsend but with close ties to fellow traders in Seattle.

No one has yet published a general history of Chinese in Port Townsend. The best effort thus far is a pamphlet published by the Jefferson County Historical Society in 2002, East Meets West: Celestials in Port Townsend. Using local publications and oral history, it gives many useful details. On the Zee Tai Company, established in 1878 by merchants named Ng (or Eng), it notes: in 1890, the Zee Tai Co. was the largest grossing business in Port Townsend, reportedly grossing more than $100,000."

An idea of other aspects of Port Townsend Chinese history can be gotten from the following articles on this website:

West Coast Cities 10-12-2012

Astoria 10-17-2012

Port Townsend 10-05-2012

Portland 10-05-2012

Seattle 10-12-2012

Tacoma 10-11-2012

Victoria 10-23-2012

Vancouver still to come

Others still to come

In 1866, Chinese New Year in Portland was already being celebrated by at least 200 Chinese, led by the merchant firms Ye Long and Wa Kee (Oregonian 1866-02-16, p 3). By 1869, the Wa Kee and Tong Duck Chung firms were chartering entire ships to carry cargo between Portland and Hong Kong (Oregonian 1869-11-17; 1870-11-08; 1871-08-15). By 1872 it had at least one temple ("joss-house"--Puget Sound Busuiness Directory 1872: p 174). The early economy of Chinese Portland was based on imports from and exports to China; on supplying Chinese communities, many of them miners, in areas further south and east; on providing contract labor for railroad construction and maintenance; on independent and contract farming; and most importantly, on recruiting and housing contract laborers for salmon canneries on the lower Columbia and in Alaska. This range of activities gave Chinese laborers a steady source of income, and Chinese merchants and contractors the chance to accumulate very substantial wealth. The early associations formed by those merchants was probably the Jong Wah Co. 中华会馆 , on Second Street in 1878, as recorded in the 1878 Wells Fargo directory.

The same activities, especially cannery work for which Chinese were considered indispensable, helped to protect the Chinese community from racist attacks by the European-American majority. Portland indeed seems to have been graced with white leaders who were outstanding in their day for racial tolerance and courage in facing down mob violence. However, one cannot doubt that economics played a role as well. Portland needed its Chinese, and knew it. The result was that the city became a haven where Chinese could live securely and where they could take refuge, as many did, in times of ethnic strife.

Curiously, Portland’s demographic importance was not matched by importance in the sphere of overseas Chinese culture. The city never had its own Chinese-language newspaper, whereas San Francisco, Victoria/Vancouver, Honolulu, and New York had several. As late as the 1940s, Portland's Chinese quarter had few if any buildings in the hybrid Sino-Western style that reflected the cultural pride of Chinatowns in San Francisco, Victoria, and Chicago. And Portland, unlike those and other cities, seems rarely to have attracted lengthy visits by Chinese poets, essayists, and other intellectuals. It was a working community in those days, with an educated, public-spirited merchant class but, perhaps, not much interest in the old-world splendors of Chinese civilization.

The history of Portland's Chinatown has been exceptionally well studied. The best book on the subject is Rose Marie Wong's Sweet Cakes, Long Journey: The Chinatowns of Portland, Oregon. (Seattle, 2004).

The following articles that mention Portland appear on this website:

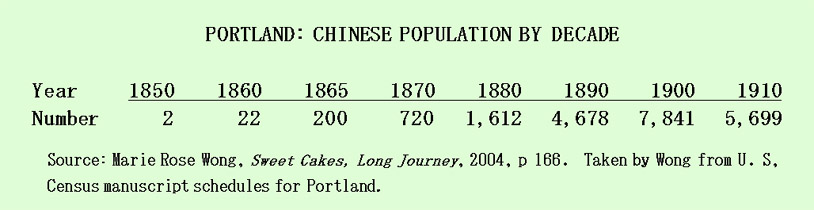

Until World War II, Portland was the Chinese capital of the Pacific Northwest. The 1878 Wells Fargo's Directory of Chinese Business Houses listed 36 businesses. In 1880 it had many more Chinese residents than any other city in the region and probably more than any other North American city except San Francisco and Sacramento (with 1,781 Chinese--www.yeefow.com/past/1850.html). By 1890 Portland had passed Sacramento, which had only 4,371 Chinese residents, about half in the rural parts of Sacramento county. By 1900 it was the third largest Chinese settlement outside Asia, surpassed in that year only by San Francisco (13,954 Chinese—Sweet Cakes, p 153) and by Honolulu (9,061 Chinese—Lai, J. Chinese Historical Soc. 2010, p 96)

1874. The first mention in the U.S. of the name "Chinese Masons” for the secret society later called the Chee Kung Tong appears in a newspaper in Portland, not--surprisingly--in San Francisco

1876. Goon Dip, later to become a major Chinese figure in the Pacific Northwest, is said to have come as a youthful immigrant from China to Portland.

1880s-1890s. Leading Portland Chinese like Seid Back and Moy Back Hin maintain cordial relations with the city government, helping to avert anti-Chinese violence.

1884 Portland merchants are said to be financing the smuggling of illegal Chinese immigrants

1884, 1893, 1899, 1904 Portland too plays a role in major opium smuggling cases.

1886 The Knights of Labor convene the Anti-Chinese Congress in Portland.

1886 Portland agitators fail to expel Chinese residents, due to the strong stands taken by the mayor and the Oregonian 俄勒岗州钵仑排华无效.

1886 One reason why Chinese were not expelled: mainly Portland residents, they formed the backbone of the cannery industry of the lower Columbia River, “the leading manufacturing industry north of San Francisco.”

1887 Sir Lionel Sackville-West, the British Ambassador to the U.S., tries smoking opium in Portland’s Chinatown.

1888 A cast iron bell is cast for a Suijing Bo temple, probably in Portland. The bell still exists, in Portland’s Gee How Oak Tin Association.

1892-1904 Chinese companies in Portland join San Francisco in supplying labor for the gigantic San Francisco-based Alaska Packers Association.

1893 Portland is reported to be the American focus of a major Canadian-American smuggling ring.

1893-1920s List of Portland-based cannery labor contractors, with some biographical details about many of the Northwest's richest Chinese. The city was second only to San Francisco in the number of contractors based there.

1901 The Kwong Lung Tai Co., one of Portland’s principal labor contractors, advertises itself as a supplier of goods, not services.

1901 The “beautiful Que Qui” flees to Portland en route to Hong Kong.

1903 The presence of the Bow Leong Tong secret society is first recorded in Portland.

1903 Lee Son Sai’s splendid funeral in Portland, with picture.

1905 Portland’s Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition does not have a locally organized Chinese pavilion—just about the only American world fair to lack one.

1907 Doc Ing Hay, famed Chinese herbalist of John Day, Oregon, joins Portland’s Chee Kung Tong secret society.

1908 Which cemetery formerly contained a memorial stone pictured in a Portland newspaper? It may be the oldest image of a Chinese cemetery anywhere in Oregon.

1909 Homer Lea, military advisor to both the Baohuanghui and Sun Yat-Sen, outlines a potential Japanese attack on Portland and Seattle.

1909 Portland’s Chinese community makes its presence felt at Seattle’s AYP Exposition, signaling a shakeup in the latter city’s leadership.

1909 Genetics and world fairs: the Reverend Fung Chak of Portland and family 冯牧师家族与万国博览会结缘.

1912 The Chee Kung Tong secret society mysteriously disappears in both Portland and Seattle.

1914 The presence of the Bing Kung Tong secret society is first recorded in Portland. By then it probably had replaced the Chee Kung Tong.

1920s-present. Three generations of Portland’s Wong family work in Alaska canneries. Educated and middle class, they regard cannery work as an ideal summer job.

1930s. Portland’s CCBA still has some of the metal boxes used to send the remains of Chinese back to China for reburial.

1930s The interior of the Tung Wah Coffin Home in Hong Kong, showing stacked boxes containing the remains of Portland and other Chinese.

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

Chinese had arrived in Steilacoom by 1860, when the Puget Sound Herald (1860-08-31) reported complaints about sanitation at a Chinese restaurant there. A Chinese who had already lived there for two years was murdered in 1862 (PSH 1862-7-10). The first Chinese in Tacoma itself are said by one secondary source (Tacoma News 1936—11-30) to have arrived in the late 1860s, attracted by rumors of the railroad terminus; one is supposed to have started a laundry and the other to have become a truck gardener. We doubt that rumors of the railroad terminus existed as early as that, however, and therefore doubt the source.

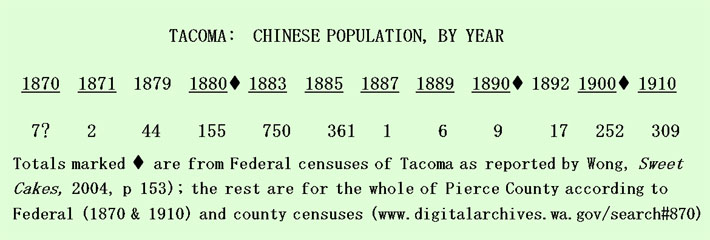

The first solid record of Chinese in Tacoma is not earlier than 1873 (the 1870 census record reported in the box above was for all of Pierce County, which included Steilacoom). In 1873, 750 Chinese laborers are supposed to have worked on the final section of the transcontinental Northern Pacific rail line as it approached what would become the city limits (Tacoma News Tribune 2011-12-23). The Oregonian (1873-9-13) reported that “a large number of Chinamen” had erected buildings, and that one “Chinese merchant evidently has faith in Tacoma as the [railroad] terminus, for he has taken a lease of some ground for five years at a round [large] figure.” In 1874, Tacoma had enough Chinese residents for a gala New Year celebration (Oregonian 1874-2-18). In 1877, Chinese and Indian hop-pickers were said to be working together in the Puyallup hop fields (Oregonian 1877-09-04). In 1878, Chinese were fishing off the Tacoma docks and flying kites there (Oregonian 1878-03-15, 1878-04-25). In 1879, Tacoma witnessed the birth of its first Chinese baby (Oregonian 1879-01-13). In 1885, the city had not only a substantial Chinese community but a well-regarded Chinese Christian preacher, Moc Tian Hui (Oregonian 1885-01-18). In 1886, the size of that community had been reduced to one.

The following articles that mention Tacoma appear on this website:

TACOMA

Except for Vancouver, Tacoma is the latest of the major cities of the Pacific Northwest. Its Chinese community came late as well. Then, after a decade of growth, it fell to zero due to the expulsions of 1885. Nothing as extreme happened to Chinese in any city of comparable size anywhere in the U. S.

1885 Tacoma’s leaders boast about the “Tacoma Method” for peacefully (i.e., with—mostly--non-lethal violence) driving all Chinese out of their community. The chief conspirators are the Committee of Fifteen.

1885 White Tacoma ladies join in looting the just-emptied Chinatown before it is burned to the ground.

1885 At least 30 Chinese businesses—general stores; shops of tailors, herbalists, and butchers, laundries, and a boarding house—are destroyed.

1885. Tatsuya Arai starts a restaurant in Tacoma, one of the first Japanese-owned restaurants in the U.S. Presumably it was not damaged when the Chinese were expelled in the same year.

1886 Seattle mobs attempt to copy Tacoma in expelling all Chinese. Due to the courage of few civic leaders, they fail.

1886 Portland’s mayor and leading newspaper, in striking contrast to their Tacoma counterparts, protect the city’s Chinese from expulsion.

1888. Edwin Gardner, an astonishingly corrupt former customs official, is arrested for arranging the smuggling of 500 pounds of opium from Canada to Tacoma.

1892 The Committee of Fifteen, which still exists, declares that it will not allow Chinese back into Tacoma even though Hong Kong merchants are unwilling to buy flour shipped from that city. The Northern Pacific's Steamship Line is not pleased.

1907 A senator from Tacoma plays a role in the Federal Government’s decision to move its Chinese detention facilities from Port Townsend to Seattle.

1909 The Japanese government donates the AYPE’s Formosa Tea House to the Tacoma YWCA. As Japan had just seized Formosa (Taiwan) from China, the gift might have caused trouble in cities with a larger Chinese population.

1926 Movie makers have to build a fake Chinese restaurant, the Golden Dragon, in Tacoma when they fail to find a real one

2010 The long-term cost to Tacoma was high in demographic as well as economic terms. Tacoma still has many fewer Chinese than comparable cities elsewhere in the region.

2011 Tacoma dedicates a Reconciliation Park on the site of the former Chinatown to show that it regrets the days of the infamous Method.

The neighborhood of Tacoma saw sporadic efforts at white settlement from the early 1830s onward, when the (British) Hudson’s Bay Company built a fort and farms on Puget Sound at Nisqually, 30 kilometers south of Tacoma. The transfer of the region to the United States in 1846 brought a halt to Company activities. This change opened the way to settlers from the well-established white communities of Oregon, despite serious fighting between Americans and local Indian tribes. Steilacoom, on the Sound 20 kilometers south of Tacoma, was incorporated in 1854. However, the future site of Tacoma remained empty of white Americans until the late 1860s, when speculators began to see the high ground to the west of the Puyallup Delta as a good place for a city, with a deepwater port and potential for good rail communications to the south and, eventually, the east.

| ||||

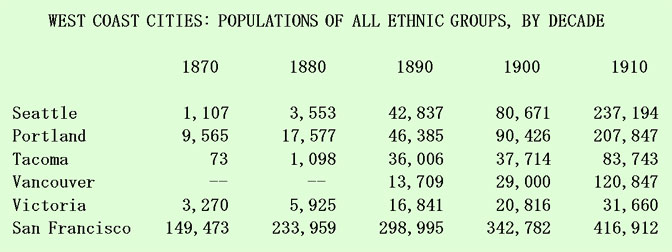

Chinese in the Pacific Northwest became increasingly concentrated in cities from 1880 onward. In the late 1850s through 1870s, they had been quite dispersed. The majority were gold miners or servicers to gold miners who had to live where the gold was found. In later years, however, gold became scarcer and rural areas more dangerous with the growth of white hostility, while the ballooning cities of the region offered relative security and a greater range of economic opportunities. Hence, urban Chinatowns grew even while, due to 1882's Chinese Exclusion Act, the overall population of American Chinese fell.

The importance of urban Chinatowns was closely linked to the importance of the cities in which they were located. As the following table shows, the relative size of those cities shifted sharply during the late 19th century. Fewer such shifts occurred in the 20th century. In 2010, the ranking of big Northwestern cities remained almost the same as in 1910, except that Vancouver's population (603,000) had risen to rival that of Seattle (608,000)

The terrible years of 1885 and 1886, when Chinese were violently expelled from many Western towns and cities, form a watershed for historical data. Very few Chinese-language historical documents survive from the pre-expulsion era in the Pacific Northwest, and early English-language writers, in a position to talk with Chinese pioneers and to witness their activities, were all too often blinded by ignorance, uninterest, or prejudice. As a result, surprisingly little is known about Chinese in this region, at least on the American side of the border, in the quarter-century between their arrival and the outbreak of the anti-Chinese riots of 1885-6. More data on that quarter-century survives in Canada, where violently racist attitudes were less prevalent and legal protections more effective. But still, that initial 25-year period, when Chinese populations reached an early peak and when distinctively North American Chinese institutions first came into being, remains obscure in many parts of the region. One of the goals of this website is to aid in shedding light on that poorly known but critically important span of time..

Seattle was settled by European-Americans earlier than Tacoma but remained a small town until the 1880s when newly built railroads, recently discovered deposits of high-grade coal, cheap hydro-electric power, deep-water harbors suited to steamships, and a central location made it a natural entrepot for regional and overseas commerce. It also became a financial center, serving the giant lumber mills and shipbuilding centers that dotted the shores of Puget Sound, numerous salmon canneries, coastal shipping firms, and large and small exporters focused on Canadian and East Asian markets. By the early 20th century, Seattle's better harbors as well as its coal and proximity to Alaska had given it a significant advantage over Portland. By then also, Seattle had pulled well ahead of Tacoma, partly due to its greater volume of trade with Asia. While Tacoma and Seattle had similar natural resources, the latter had an internationally known university, foreign trade-oriented leaders, and a history of cooperation between white and Asian businesses.

Not much has been written about Seattle's Chinese residents before 1886, the year of the driving-out. Chen Cheong had a cigar factiory there, which also sold sweetmeats and fancy goods, in 1872 (Puget Sound Business Directory, 1872). Historians of the pre-1886 period have tended to focus on the careers of certain Chinese entrepreneurs, especially Chin Chun Hock 陳程學 and Chin Gee Hee 陈宜禧, who are said to have arrived in 1860 and 1875. Both played a role in building the railroads that served Seattle and other Puget Sound communities. At first together and later separately, they also acted as importers, shop proprietors, employment agents, and contractors.

Chin Gee Hee's career has been fairly well studied (click here) but that of Chin Chun Hock is much less well known. The most evocative description of Chin Chun Hock's activities comes from a credible but undocumentable source: Mrs. Ruth Price, the executive secretary of Seattle's China Club in the early 1950s. Having been assigned by the Club to conduct preliminary research on pioneer Chinese Americans, Mrs. Price took the bit in her teeth and plunged forward on a major research project, filling an "impressive stack of notebooks" with data from library sources and interviews "with members of the Chinese colony." At least some of the older members would have known associates of Chin Chun Hock--for instance, Chin Quong (1857-1935; arrived 1868) and Woo Gen (active until at least 1924; his son, David H. Woo, lived until 1992). The notebooks have disappeared, and Mrs. Price was not a trained researcher. Yet we feel that her description, as recorded by Lucile McDonald in a Seattle Times article, is plausible and worth repeating:

"Mrs. Price tracked down the story of Chin Chun Hock, whose Wa Chong Co. existed until a couple of years ago. Its proprietors then said it was the oldest business house in Seattle.

"Chin, born in 1844, arrived in Seattle from China in 1860 and eight years later organized the company. Advertisements in 1873 listed its location as Mill [now Yesler] Street. It manufactured cigars, sold tea, and did tailoring. Chin engaged in various other enterprises, though he continued for a quarter of a century using as a symbol of his business the figure of a Chinese weighing tea.

"Chin once remarked that there was a swamp behind his first store and he shot wild ducks there. The wooden structure built on stilts over the march stood on the later site of the Pacific Building.

"Contracting was one of Chin's activities. He supplied labor for building the coal railroad to Newcastle [i.e., the Seattle and Walla Walla Railroad, begun in 1874] and was quoted as saying 'I graded Pike, Union, Washington and Jackson Streets. At one time the city owed me $60,000 for six months. I had to sue to recover it.'

"Chin also exported Pacific Northwest products to China, as much as 4,000 barrels of flour to Hongkong in one shipment." (Seattle Times Sunday Magazine1955-9-11, p 2)

| ||||

First settled in 1843 and incorporated in 1851, Portland is the oldest city in the Pacific Northwest. It owed its rapid rise to its location, on the Willamette where it joined the Columbia, a short distance from the Pacific. This made Portland simultaneously a seaport, the main market and service center for the rich farms of the Willamette Valley, and an entrepot for the mineral wealth of the vast Columbia drainage basin, which covered more than half of the Northwest. In the 1870s, its two river valleys provided yet another advantage to Portland: practicable rail routes to the eastern U.S. and California. In the late 1870s, the city became the hub of the salmon canneries on the lower Columbia, then the most important industrial complex north of San Francisco.

Portland remained the biggest city in the region until the 20th century when it was finally passed by Seattle, with its better seaport and more direct access to Alaskan and Canadian resources. The decisive factor may have been the fact that the harbor of Portland (and of Astoria) was difficult of access, due to the sandbar at the mouth of the Columbia. Pacific shipping was increasing in volume and ships were growing larger. Hence, shipowners, insurers, and international traders came to prefer the deeper, safer harbors of Puget Sound and the Straits of Georgia--that is, the Salish Sea.

PORTLAND

ASTORIA

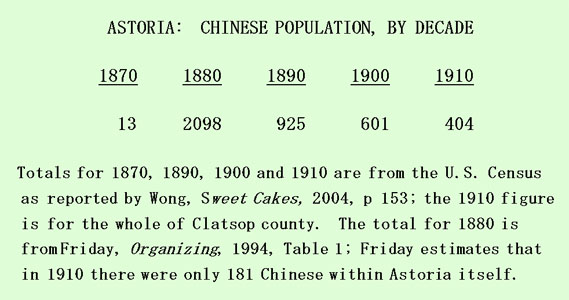

To northwestern Chinese, Astoria was a minor immigrant gateway and a major salmon fishing town, with dozens of canneries and potential jobs that not only were open to Asians but also offered some hope for advancement. Astoria itself had a substantial Chinatown in the 1880s and nearby Portland had a larger one. Chinese in both places, partly due to their economic importance in the cannery industry, were rarely persecuted by local whites.

The earliest European-American settlement on the West Coast, Astoria was founded at the mouth of the Columbia in 1812, on the orders of the fur trading magnate, John Jacob Astor. He saw the settlement as having a single purpose: gathering furs for shipment directly to China. However, Astoria did not do well in competition with the fur-trading British Northwest Company based at Fort Vancouver, in what is now Washington. This meant that Astor's settlement stayed small and poor until the 1840s, when American settlers began arriving and the British left. Once Oregon had become part of the United States (in 1846), Astoria began to grow, serving as a customs post and stopping place for ships on the way to Portland. In 1860 it had 252 residents. In 1870 it had 639. Shortly after that, entrepreneurs began building canneries to capitalize on the enormous runs of salmon that ascended the Columbia each year. By 1880, Astoria had become a small city, with enough canneries to support a seasonal population, many of them cannery workers, of 2,800. By 1890 it had almost 6200 residents. Astoria’s growth slowed after that and then stopped. Its population in 1910 (9,599) was almost the same as in 2010 (9,477). For much of that later history, it was a one-industry cannery town, prosperous enough but essentially a satellite of Portland. .

The salmon canning industry of the lower Columbia began to concentrate in Astoria, at the river’s mouth, in the mid-1870s. The two first canneries there appeared in 1874-5. One of them, that of Booth & Co., already employed 180 men, “mostly Chinamen” (Daily Astorian 1875-5-22) The number of canneries increased rapidly after that to eight in 1877 and fourteen in 1880, when three-quarters of the 2,122 Chinese in Astoria were listed as cannery men; the others were cooks, grocers, merchants, physicians, restaurateurs, gamblers, gardeners, tailors, barbers, and so forth (Friday, Organizing, 1994,

Table 1).

Life for Astorian cannery workers seems to have been relatively pleasant. In Alaska, their counterparts lived in isolation, usually tens or hundreds of miles from other canneries or settlements. In Bellingham and elsewhere on Puget Sound, prejudicial laws often confined Chinese workers to employer-provided bunkhouses on the grounds of the canneries. In Astoria, however, workers could frequent a substantial Chinatown and, further, were near a major city, Portland.

A decline of the Chinese population was already evident by 1890 but after that the drop was less sharp than the above table implies. From 1860 to 1900, federal censuses had been carried out on June 1, when the canneries already had their full complements of seasonal workers, many of them Chinese, However, in 1910 the date of the census was moved from June 1 to to April 15, before most workers had arrived for the salmon season. How many Chinese were living and working in Astoria on June 1, 1910? We cannot know for sure, but their numbers may not have been much less than in 1900. In 1910 the canned salmon business was still good, Astoria was not particularly anti-Chinese, and neighboring Portland still had numerous Chinese residents. Many Portland Chinese are known to have worked seasonally at Alaskan canneries until the 1940s or even afterward. Many others must have continued to spend their summers in Astoria, by then only an hour or two from Portland by rail. As Friday concludes, "In spite of shrinking opportunities and the increasing power of contractors in the town, workers continued to prefer Astoria jobs to those in [Alaskan] bunkhouse villages, for the cannery town offered them a much richer experience."

Astoria's Chinese community and cannery industry are described in rich detail by Chris Friday, Organizing Asian American Labor: The Pacific Coast Canned-Salmon Industry, 1879-1942. (Philadelphia, 1994). A valuable compilation of primary sources is that of Liisa Penner, The Chinese in Astoria, Oregon, 1870-1880 (a MA thesis, 1990, on deposit in the Astoria Public Library).

The following articles on this website mention Astoria:

1878-1906 List of cannery contractors in Astoria. With, when known, names in Chinese characters and other data

1886 Why Chinese were not expelled from Astoria in the driving-out years.

1886 Astoria is one of the places visited by Hong Too, the "general bone gatherer for the Sam Yup Co," in connection with exhuming Chinese bodies and reburying them in China.

1887 Goode’s expert, objective description of Chinese workers in the Columbia river canneries.

1888 The "Boo Leong Hong" is named by the (outspokenly anti-Chinese) Astorian as one of the main highbinder (criminal) secret societies in Astoria.

1893 Customs officials in Astoria seize a major shipment of opium and initiate one of the largest nineteenth-century opium and immigrant smuggling cases on the West Coast.

1904 Chinese leaders in Astoria and Portland want Ah Oy, a fashionable prostitute, deported. It is not known why.

| ||||

The first Chinese in Astoria may have been the first in the Pacific Northwest since Meares brought his Chinese craftsmen and sailors to Vancouver Island in 1788. An article in the Washington (D.C.) Daily Globe, dated 1854-11-22, reads "The oldest inhabitant of Astoria, Oregon, is an old half-breed Negro and Malay, who had lived in the settlement forty-six years, and is now with his family, of partly Indian extraction, well to do in the world." Would a traveler from the Malay Peninsula in those days have been partly Chinese? Probably. Would he or she have produced an African-Asian child if he/she had come to North America? Quite possibly. Could that child have come to Astoria forty-six years before 1854--that is, before Astoria was founded and and only three years after Lewis and Clark first reached the mouth of the Columbia? Conceivably, but one's credulity is strained.

Numbers of Chinese must have begun arriving at Astoria by ship in the early 1860s, on the way to Portland and the gold mines of the upper Columbia. They definitely came, and some probably stayed, in the late 1860s, when several ships from California and Hong Kong reached Astoria with Chinese on board (see, e.g., the Oregonian 1866:08-26, 1867-090-6)

1860s-1908 Victoria becomes the largest opium refining center outside Asia 域多利 - 加拿大最大的 鸦片烟产地 With lists of refiners, most of them respected merchants in Chinese and English

1871. First mention of "Chinese Masons", the Hong Men or Tiandihui secret society, in North America, in Victoria.

1875-1887 Victoria’s Tam Kung Temple is built, the oldest and most complete Daoist temple in Canada. 卑斯省域多利谭公庙

1880s Opium brand names, many from Victoria, on opium cans found at early Chinese sites in central British Columbia and Idaho. 在加拿大卑斯省发现的名牌鸦片烟

1884-1885 Dedicatory inscriptions for the Chinese Benevolent Association’s meeting hall and shrine in Victoria. 加拿大域多利埠中华会馆大堂

1885 A highly intelligent white prostitute-addict from Victoria testifies before a royal commission 鴉片煙友

1885 Victoria Chinese begin one of the earlier projects for repatriating bodies of sojourners to China.

1886-1890 Victoria merchants win an opium price war against a giant Macao exporter

域多厘商人压倒澳门烟商

1888. The first explicit English-language mention in Canada of the Chee Kung Tong secret society, in Victoria.

1890-1891 A public-spirited cartel? The modest profits of Victoria's opium refiners 域多厘烟商利润低

1893 Victoria is featured in two spectacular opium smuggling cases, one involving a major conspiracy and the other a white mother and daughter from Port Angeles

1895 Lady Ishbel Gordon Aberdeen joins her husband, the governor general, on an official visit to a Victoria opium factory. Unlike MacKenzie King in 1908, she is not shocked

1895 Victoria’s Colonist newspaper denies Britain's motive for starting the first Opium War. It was not to force China to accept British traders' opium.

1900 Chinese women in Victoria begin to organize, for famine relief and other charities 年卑斯省教会妇女关心社会

1903 Victoria’s beautiful Harling Point Chinese Cemetery comes into use 加拿大.域多利:哈宁角华 人坟场

1903 onward Chinese ethnic-linguistic subdivisions within Victoria’s Harling Point cemetery从墓碑认识移民故里

1903 The first branch of the Chinese Empire Ladies Reform Association is established in Victoria. Is it: real or a public relations fantasy? 加拿大保皇女会 : 域多利, 温哥华/二埠

1903 Kang Tongbi in Victoria -- A bright teenager leads CELRA, the Ladies' Baohuanghui 保皇女会领袖 - 康同壁在西北角的活动

1904 The Great Northern’s new super-ship, the S. S. Minnesota, stops in Victoria to pick up 172 Chinese crew members before its maiden voyage across the Pacific.

1905-1907 A time capsule and plaque are deposited at the Baohuanghui’s (Empire Reform Association's) original world headquarters in Victoria

1906 An image of a Chee Kung Tong membership badge on cloth, issued in Victoria 加拿大域多利

1906 The Portland, Seattle, and Victoria branches of the Baohuanghui present a petition to visiting Chinese imperial commissioners demanding the abdication of the Dowager Empress of China.

.

1907 A revolutionary anti-Manchu “tianyun” date appears on a shrine in the Dart Coon Club, Victoria. 加拿大 域多利 達權社

1911 An art nouveau landmark: Victoria's Hook Sin Tong Building 巍巍大厦. 福善有堂

1937 Only 13 women are among the 661 individuals included on the list of bodies to be shipped by Victoria's Chinese Benevolent Association to China for reburial. 域多利女先友的执运纪录 (women) (indivs)

1959 The only existing photograph of boxes stored in the bone vault of Victoria’s Harling Point, waiting to be shipped back to China

VICTORIA

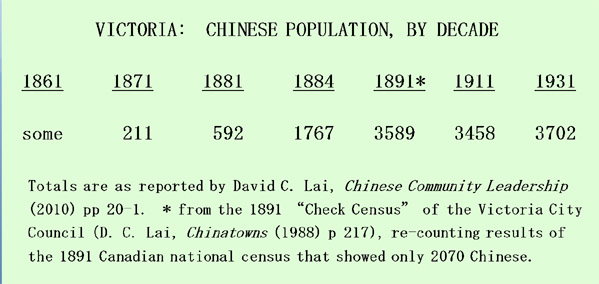

Victoria was the Chinese capital of western Canada from the late 1860s through the 1890s, and shared that status with Vancouver until the 1910s. Its Chinese community is old. Without undue exaggeration and ignoring the claims of Portland and Sacramento, Wikipedia can state that “the city's Chinatown is the second oldest in North America after San Francisco's.” The Chinese merchant firms of Victoria were prosperous and unusually stable, partly due to their near-monopoly of opium refining in the western hemisphere and partly due to the good relations they maintained with the city’s white elite. Anti-Chinese editorials and violence were uncommon in Victoria, the Chinese presence was viewed neutrally or even positively by at least some non-Chinese, and Victoria’s Chinatown, though small in comparison with several U.S. Chinatowns, maintained high standards of culture as well as close connections with China.

Fort Victoria, founded by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1843, the same year as Portland, was no more than a fur trading post with a good harbor until 1858, when the Frazer river gold rush began. An influx of gold seekers and their parasites pushed the population up rapidly. Victoria was laid out as a city in 1861, became the capital of the combined provinces or Vancouver Island and British Columbia in 1866, and dominated western Canada until about 1890, when the newly completed Canadian Pacific Railroad caused an abrupt shift of population and economic power to Vancouver on the mainland. By the mid-1890s Victoria’s growth was beginning to level off, and it had already been passed in population size by the other principal cities in the region. Interestingly, it did not die in spite of the competition of Vancouver. Its continuing status as the provincial capital helped. So did the major coal mines of Nanaimo and Cumberland, a productive logging industry, and a wealthy, economically active Chinese community.

The earliest Chinese arrived in 1858 as part of the Frazer river gold rush (Victoria Gazette, cited by Morton 1974, pp 5-6). Within a year or so, thousands were passing through the city en route to the gold mines. A few stayed, however. Among the most important were two brothers, Loo Chock Fan and Loo Chew Fan. In 1858, the two founded Kwong Lee &Co., which became the largest Chinese firm in the province (Lai 2010: 53). In 1860, the wife of Loo Chock Fan arrived, becoming the first Chinese woman in Canada. By 1862, Kwong Lee was paying taxes that were second only to those paid by the Hudson’s Bay Company (Morton 1974: 12). Other Chinese residents included several traders, a doctor, a fruiterer, a washman, and an apothecary. 1861 saw the birth of the first Canadian Chinese baby, Won Alexander Cumyow, later to be a key figure in the Chinese history of the region.

The Chinese elite in Victoria was more prominent in the eyes of the white majority than their counterparts in most other North American cities. Their businesses played an important role in Victoria’s economy. The majority of the largest ones refined opium, paying significant taxes over the years. Many also were labor contractors, real estate speculators, and importer/exporters. Unlike leading Chinese businessmen elsewhere in the Pacific Northwest, who almost always were self-made men, those of Victoria tended to have been wealthy before they came. The Loo brothers of Kwong Lee, Lee Yau Kain of Kwong On Lung & Co., Wong Yim Ho of Tai Soong & Co., and Lee Yick Tack of Tai Yune Co. all came from rich families in China or the U. S. (Lai 2010: 52-61). Those China-based families must sometimes have owned substantial parts of the Victoria firms managed by their sons and nephews.

Kwong Lee & Co. and Tai Soong & Co., the two largest firms, maintained close connections with branch stores and affiliates in the British Columbian interior, in Yale, Lilloet, Quesnelle Forks, Quesnel, Barkerville, etc. Opium cans marked with the seals of Kwong On Lung, Tai Yune, and Tai Soong have all been found at Chinese gold mining sites in the Cariboo (click here), and large quantities of foodstuffs, clothing, Chinese tobacco and liquor, tools, and ritual supplies were undoubtedly distributed along the same routes as the opium. Victoria remained the center of this hinterland trade until the 1890s, when Vancouver began to take its place.

Despite its loss of commercial primacy, Victoria’s Chinatown remained stable in size well into the 20th century. This may have been partly due to the prestige conferred by Kang Youwei’s choice of the city as the first world headquarters of the Baohuangwei, the Chinese Empire Reform Association. While the wealth of its Chinese community may have influenced Kang in this regard, he may also have been attracted by the relative security and cultured atmosphere of that community. An example of the cultural standards of the Victoria Chinese is the main hall of the Hook Sin Tong association, built in 1911 (click here). Many buildings in San Francisco’s Chinatown were designed and constructed at about that time, due to the destruction of the1906 earthquake. Yet very few have interiors that can match that of Victoria’s Hook Sin Tong in terms of elegance and taste.

The following articles on this website mention Victoria:

| ||||