Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee (CINARC)

This page was last updated: August 30, 2018

(UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED ALL DATA ON THIS PAGE COMES FROM THE EDITORS' OWN RESEARCH ON PRIMARY SOURCES & ARTIFACTS)

INTERMARRIAGE 两情相阅.异族通婚

1. Legal Issues. Laws banning "miscegenation," the mixing of races

or interracial marriage, came increasingly to be applied to Chinese-white relationships in the later 19th and early 20th century. The 1940s were the highwater mark of such laws. By 1944, marriage between Chinese and whites had become illegal in 14 states, all in the West and South. In the Pacific Northwest, such marriages remained legal only in Washington and British Columbia.

2. Gender. Almost all such marriages were between Chinese men and white women. Before 1920, only a handful of cases are recorded of Chinese women in North America marrying white men.

3. Location. Though not rare in the American West, Chinese-Caucasian marriages were more common east of the Mississippi where anti-Chinese prejudice was less intense.

4. Hypergamy. Many but by no means all were economically hypergamous, with poorer white women marrying richer Chinese men. But Chinese-white marriages were not necessarily hypergamous in a social sense. The social status of Chinese husbands in the U.S. and Canada was often as low as that of their wives.

5. Status. In a surprising number of cases, the wives’ status was independently high, due to family wealth, education, and/or religious prestige. Many such wives were female missionaries who married Chinese converts or students from English language classes.

6. Exploitation. Asymmetric, exploitative marriages were common, on the part of both white and Chinese spouses. Such marriages ended in abandonment, separation, divorce, or worse. Some even ended in suicide or murder, but not often. When these extreme actions did occur, they were as likely to be committed by white wives as by Chinese husbands.

7. Acculturation. Mutually beneficial, stable relationships seem also to have been fairly common. It must have helped if, as was often true, the Chinese husband was in the process of acculturating to white society, and if the white wife was trying to acculturate in the other direction. Perhaps because they were often teenagers (their husbands tended to be in their thirties or forties), the wives showed a good deal of cultural adaptability. Many seem to have learned to speak Chinese.

8. Obstacles. The main obstacles to success in such marriages, as one would expect, were (a) cultural barriers between husbands and wives and (b) racial prejudice on the part of families and the wider white and Chinese communities.

9. Racism on the part of whites was not only pervasive but dangerous, especially in the West and Northwest. Marrying in spite of this took real courage. By the time he could afford to marry in North America, the average Chinese husband had learned to cope emotionally with physical threats and legal persecution. The average white wife, however, probably had not. The stubborn bravery often shown by such wives is one of the more inspiring themes of Chinese American history.

10. Reasons for Marrying. An early study in Chicago found that Chinese men married white women because they “long for home life more even than most bachelors do” and that a sample of 25 recent white brides gave the following motives for their marriages: "Love. Kindness. Money. A home."

She showed touching grief when shown her husband’s body, but the hard-bitten Chicago detectives were not impressed. They still thought she was a murderer. Her husband’s brother Frank told the police that she and Charles had quarreled violently a week before about his plans to go back to China and not to take her. The police themselves seem to have looked into but rejected more exotic motives, including a nation-wide smuggling ring and a love quadrangle featuring George Norn, a strikingly handsome Chinese friend, and Alice’s sister Emma.

The case came to trial in December and, to the fury of the police and Frank Sing, Alice was acquitted. In spite of the sensational nature of the murder, the evidence against her was not strong. The jury may also have been influenced by her grief and devotion. As she told a newspaper reporter a few days after the murder,

“From the first time I saw him I loved him. There was something about him that fascinated me. He was quiet, lithe, and graceful. He was mysterious, and I guess that is what attracted me. He never laughed out loud no matter how happy he was. He chuckled…”

1913 White Wife Murders Chinese Husband in Chicago

In 1913 a white Chicago woman named Alice Davis Sing was alleged to have found a more direct way of getting rid of her Chinese husband, one Charles Sing -- she took a knife and stabbed him to death in their home at 3460 Archer Avenue.

Alice had been a Christian missionary in Kansas City’s Chinatown. That is where she got to know Charles and several other Chinese men, described by her father as “admirers.” She fell deeply in love with Charles. After the murder, one Chicago journalist noted that unsuspecting white girls like Alice quite often “were lured into [Chinese men’s] parlors, stores, and chop suey joints by their pleadings and outward gentleness, then, captivated by the apparent luxury of their lives and apartments, they visit them again and again until their ruin is accomplished.” Alice’s ruin entailed not only marriage to Charles but conversion to her husband’s religion, a tendency to speak in Pidgin English, and a fondness for Chinese clothing, as shown by the lace-trimmed cheongsam dress she is wearing in this photograph

Alice Davis Sing in September 1913, charged with murder

Reasons for Marrying Chinese Men

嫁华人的好处

An article that appeared in 1907 in Victoria's Daily Colonist, taken more or less verbatim from the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, states that "almost 200 white girls in Chicago are married to Chinamen." Interviews with twenty-five of the most recently married suggested that their reasons were much the same as those that motivated white women to choose white men: love, kindness, money, the desire for a home, and--not a motive in most white-on-white marriages--opium addiction.

One year earlier, in 1906, Ella May Clemmons in San Francisco, the wife of Wong Sun Yue, had the following conversation with a reporter.

"Your husband, where is he?"

"Cleaning bricks" was the reply. She lifted her head proudly. "He earns $2 a day. He works hard and uncomplainingly. He is good and kind, but all Chinese are good and kind to their wives, for that matter."

Ms. Clemmons was already in her forties, and Wong Sun Yue was her third husband. She would have known what she was talking about.

Applied originally to marriage between black men and white women (but in practice not to sex between white men and black women), laws against miscegenation (racial mixing) were gradually extended to cover Chinese and other "Mongolians" as well as Native Americans and "Malays" (Filipinos) In 1896, marriages between whites and Chinese were prohibited in Arizona, California, Nevada, Oregon, and Utah, and probably Mississippi and South Carolina too. By 1944, the ban had been extended to fourteen states: Arizona, California, Georgia, Idaho, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Virginia, and Wyoming.

The early anti-miscegenation statutes of several states had holes in them, however, which meant that interracial marriages did sometimes occur in those states until after 1900. In California, for instance, it was only in 1902 that the Civil Code was finally amended to make all marriages with "Mongolians" (i.e., Chinese and other East Asians) definitively null and void, and even then Mongolian-white marriages contracted in other states continued to be regarded as valid by California courts. In certain states (for instance, Wyoming) it was an actual crime, punishable by law, for a white woman and a Chinese man to be married, even if the wedding occurred outside the state.

Anti-Miscegenation Laws 中美通婚.法令不容

| ||||||

1900 Chinese Ex-Husband Tries to Murder White Wife in Victoria

Chinaman Uses Axe

-------------------

Tries to Kill His Former Wife, a Pretty Irish Girl

-------------------

By Leased Wire.

Vancouver, B.C, Tuesday, Aug 7

---Christine O'Reilly, a pretty Irish girl employed as a waitress in the Water Front Restaurant, is in the city hospital with a long scalp wound, which nearly caused her death. It is the result of an attack upon her with an axe by her former husband, a Chinaman named J. D. Johnnie. The latter was incensed at her refusal to become reconciled to him and would have murdered his ex-wife but for the timely interference of another waitress, who grappled with the Chinaman and disarmed him..

Anger at separation or the threat of separation also motivated Chinese husbands of white wives, as shown by following article from the Seattle Times, August 7, 1900. Here it is, reproduced complete.

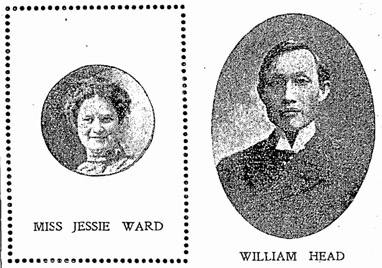

The effects of miscegenation: Sino-American children in Chicago, 1924. (See below, Lotty Barbery Kubska). NARA Exclusion Files photo

Sources: San Francisco Call 1896-12-27 & 1903-10-16; California Law Review 1944, vol 32, no 3: pp 269-280. For Wyoming, see Salt Lake Herald 1881-06-07, p 1 or Sacramento Daily Record-Union 1881--06-07, p 1. For late adoption of law in Idaho & Wyoming, see H. Karthikeyan & G. J. Chin, 2002, "Preserving Racial Identity," Asian Law Journal 9, 1, p 17

Sources: For intermarriage in Chicago, see the Victoria Daily Colonist 1907-01-30; for the Clemmons interview, see the Pullman [WA] Herald 1906-10-06

Lee Po, his wife (Gertrude Matthews), and one of their five children. Los Angeles Herald 1892-12-04.

1857 “Of the many Chinamen in New York not a few keep cigar stands upon the sidewalks. Their neighbors in trade are the Milesian [Irish] apple-women. Twenty-eight of these apple-women have gone the way of matrimony with their elephant-eyed, olive-skinned contemporaries, and the most of them are now happy mothers in consequence .”(Harper’s Weekly, 1857-10-03, p 630)

1870 “It is a fact worth noting that the Chinese who come to New York invariably marry Irish wives.” (Appleton’s Journal 1870, p 444)

1878 “Among the thirty thousand or more Chinese residing in San Francisco are some half dozen wedded to white wives.” (San Francisco Chronicle 1878-06-02)

1885 “Some twenty Chinamen in Chicago have married white girls, principally Germans, although one Irish girl is the possessor of a yellow liege lord.” (Chicago Tribune 1885-04-15)

1899 “...curious alliances or mesalliances, perhaps one should say, of which there are several, involving the marriage of Caucasians and Mongolians, in this city [Portland] ...” (Oregonian 1899-12-10)

1907 “”Almost 200 white girls in Chicago are married to Chinamen and preside over the homes of Orientals—in Chinatown and throughout the city.” (St. Louis Globe-Democrat, quoted by the Victoria [BC] Daily Colonist 1907-01-30)

1911 “TENTH WHITE GIRL WITHIN YEAR CASTS LOT WITH CHINAMAN. Vancouver, Wash., Justice of the Peace Joins Miss Geraldine McCormack, 25 Years Old, in Wedlock with Chin Hee” (Seattle Times 1911-08-27)

1910-1950 Compiling data from the Illinois State Death Certificate database, which lists the race as well as the name or the deceased, shows that at least 15 wives of Chinese were white (6 Moys, 4 Wongs, and one each for Hong, Leong, Gin, Chan & Eng). Two were black (one Chin & one Hong)

From an earlier version of the website of the Chinese American Museum of Chicago: http://web.archive.org/web/20070509113637/http://www.ccamuseum.org/Research-2.html#anchor_7

1910-1950 Christoff has used the Chinese Exclusion Files at Chicago’s NARA to assemble a comprehensive list of white wives who applied for re-entry permits in order to accompany their Midwest-based Chinese husbands on trips to China. Only the most prosperous husbands could have afforded this. There were fourteen such wives, of the following national origins: German–6, Polish–3, "White"–3, Swedish–1, and Irish–1.

(Peggy Spitzer Christoff, Tracking the "Yellow Peril", 2001, pp 77-143)

The Geography of Chinese-White Intermarriage

中外配偶何处有

Nothing like comprehensive statistics exist for the decades that interest us here, 1850-1920. Nevertheless, a rough idea of the geography of marriages between Chinese and Caucasians can be gotten from historic newspapers and magazines, supplemented by limited data from official archives. As one would expect in view of the absence of anti-miscegenation laws there, the great majority of Chinese-White marriages took place in the midwestern and eastern U.S. They were much less common in the western U.S. and Canada in spite of the larger Chinese population of that region.

The apparent prominence of Chicago in promoting such "miscegenation" is partly due to the editors having come from that city and knowing the relevant historical sources. However, one should not underestimate the role played by the melting-pot nature of eastern cities during the late 19th century. In communities with dozens of ethnic groups living cheek-by-jowl, speaking a cacophony of languages, wearing peculiar clothes, and many very poor, Chinese did not stand out. They were no more noticeable and often had higher incomes than many recent European immigrants. Moreover, due to a public distaste for racial discrimination dating back to before the Civil War, anti-miscegenation laws were non-existent in places like New York and Chicago. So it was not hard for Chinese men to find white wives, or for white women to consider "Chinamen" as possible husbands.

The subject has been neglected although such marriages were fairly common. There was and, in some quarters still is, prejudice against East-West unions, especially when the Chinese spouse is male and the white spouse female. And yet East-West couples and their children played a major role in Chinese North American history despite the barriers they faced. This page explores several relevant issues, going well beyond the Pacific Northwest in search of cases and answers.

Reasons for Marrying White Women 娶西妇的好处

Lee Chew, the author of a witty, perceptive article for the New York weekly, The Independent, thought that a scarcity of Chinese women was the main reason, together with the chance that some white women might turn out to be, as Lee charitably suggested, "excellent and faithful wives and mothers."

"In all New York there are only thirty-four Chinese women, and it is impossible to get a Chinese woman out here unless one goes to China and marries her there, and then he must collect affidavits to prove that she really is his wife. That is in [the] case of a merchant. A laundryman can’t bring his wife here under any circumstances, and even the women of the Chinese Ambassador’s family had trouble getting in lately.

"Is it any wonder, therefore, or any proof of the demoralization of our people if some of the white women in Chinatown are not of good character? What other set of men so isolated and so surrounded by alien and prejudiced people are more moral? Men, wherever they may be, need the society of women, and among the white women of Chinatown are many excellent and faithful wives and mothers."

Source: Lee Chew, “The Biography of a Chinaman,” The Independent, vol. 15 (19 February 1903), pp 417–423.

1893-1920: Rare Events in pre-World War II North America: Chinese Women Marry White Men 罕见例子: 1920年前嫁西人华妇

The scarcity of Chinese women in the U.S. and Canada meant that any who was free to marry could pick and choose among many potential Chinese mates. Even prostitutes had no problem finding Chinese husbands, for whom it had long been socially acceptable to take prostitutes as second wives.

So it is not surprising that North American Chinese women rarely married whites. Two of the best-known cases are those of Polly Bemis in Idaho and "China Mary" Johnson in Alaska. Both were former prostitutes, both lived in isolated frontier areas with tolerant attitudes toward prostitution, and both were culturally adaptable individuals with Caucasian husbands whom they seem to have truly loved [Note 1]

Two other well-publicized cases involved the Eurasian daughters of marriages between Chinese men and white or mixed-race women. In Hawaii, Chun Afong and his wife, herself a mixture of native Hawaiian and white Chicagoan, had thirteen daughters, most of whom married white men. Perhaps the best-known of those daughters were Marie and Etta Afong, the latter considered to be the beauty of the family.

Note 1. Both women have been written about extensively. For Polly Bemis, click here. For China Mary Johnson, click here.

Note 2. Hawaiian Star 1893-10-27 p 5. See also Bob Dye, Merchant Prince of the Sandalwood Mountains: Afong and the Chinese in Hawaiʻi, U. of Hawaii Press, 1997. The image is in the public domain, from Wikipedia Commons.

Note 3. For Joseph's marriage, see the Omaha (Nebraska) Bee 1887-08-14 p 12. For Hilda's marriage, see the New York Times 1910-05-18 p 4 and the Seattle Times 1910- 05-18 p 3. The picture of Joseph is from the New York Evening World 1906-03-39 p 10. For Chinese aid to Russian Jews, see New York Times 1903-05-03 p 3.

Note 4. See Murray K. Lee, "Ah Quin," in Susie Lan Cassel ed., The Chinese in America, 2002 p 325.

Note 5. This image seems to be from another print of the negative from which a copyrighted photographic print belonging to the San Diego History Center was made. See www.sandiegohistory.org.

Note 6. Sources (all imaged by ancestry.com): 1920 Federal Census; Chinese Passenger Ship arrivals 1903-1944, NARA Microfilm ARC 646080; Ada County (Idaho) Marriage Book, vol 16, p 137.

Polly Bemis

Mary Johnson

Interestingly, in intermarriage-tolerant Hawaii, the Afong girls' engagements and weddings were described in the same gushing, non-racist language as used for white-on-white marital unions. The Hawaiian Star, for instance, wrote:

"Another young lady of the family of Mr. Afong, the millionaire Chinaman of Honolulu, has captured an American for a fiancé. She is Miss Marie Afong, and the man she is to marry is Ellis Mills . . . the young Virginian who went to the Islands a few months ago as Secretary to James H, Blount, subsequently minister to Hawaii. While in Honolulu the Secretary met Miss Marie Afong, the sister of Miss Etta who is engaged to marry Commander Whiting of the United States ship Alliance . . . It was a case of love at first sight, and when he asked [Whiting] Mrs. Afong's [permission to address her daughter she declined the honor because of the great disparity in their ages--Etta is 19 and Commander Whiting 50--but he was determined and in time won both mother and daughter to his way of thinking." [Note 2]

Etta Afong Whiting

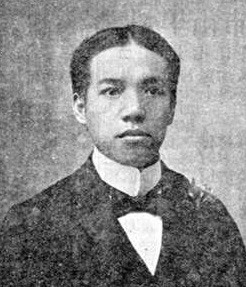

Newspaper stories about the wedding of a white American, John A, Peltry, to Hilda Singleton, the daughter of the Chinese merchant (and former evangelist) Joseph M. Singleton and his white wife Henrietta, were less gushing and, in some cases, less courteous. The Seattle Times headed the story, "New York Half-Breed Chinese Girl Marries." The New York Times treated the story more matter-of-factly but without the details would expect in writing about the daughter of an equally rich and prominent white American. The New York paper did manage to slip the fact in that Hilda was the daughter of Joseph's first wife and that his second wife, Hilda's stepmother, was also white.

Hilda's own mother, Henrietta Alton Hill, had married the Rev. Joseph Singleton (a.k.a. Ju Sing) in Brooklyn in 1887, shocking parishioners of the Central Congregational Church: "Members of the church have noticed that the young Chinaman and Miss Hill were very intimate but his intimate friends never suspected that matrimony would be the outcome. It is understood that Mrs. Singleton's friends in the church disapprove of her action."

Joseph M. Singleton/ Ju Sing, 1903

Joseph Singleton was apparently ordained as a Congregationalist or Dutch Reformed minister but later became an official interpreter and businessman. By the early 1900s he was described as a millionaire. As the head of the Chinese Empire Reform Association in New York he played an important role in calming tong wars and in raising money for the relief of persecuted Jews in Russia. [Note 3]

Yet another case, or rather cases, of white men marrying Chinese women in the U.S.: three of the seven daughters of San Diego's wealthy pioneer businessman, Ah Quin. Mamie Ah Quin married one Royal Rife, of indeterminate ethnicity; Mary married Joseph Farina, presumably Italian; and Mabel married Willie West Kennerly, an Irish policeman [Note 4]. As with Hilda Singleton and the Afong girls, having a rich and Americanized father seems to have freed Mamie, Mary, and Mabel to seek husbands outside the Chinese community. Considering that any young Canadian or American Chinese woman, especially one with money, could have had her choice among a great number of local Chinese men, the decision of Mamie, Mary, and Mabel to marry out is puzzling. Was it simply love? We do not know.

Ah Quin with most of his daughters, San Diego, 1899. [Note 5]

PAGE CONTENTS

> The rise of anti-miscegenation laws as applied to Chinese-white marriages 1/8/2013

> Defending mixed marriages 2/2/2013

Fong See-Letticie Pruett 2/12/2013

> Rare events: Chinese-American women marry white men revised 2/6/2013

Ruth Bowers 2/6/2013, revised 2/10/2013

> Why marry a Chinese man? 1/14/2013

> Why marry a Caucasian woman? 1/14/2013

> Who were the white wives? 2/2/2012

> White wives and their mixed-race daughters 2/2/2012

Alice Davis Sing murders her Chinese husband Charles Sing, in Chicago 1/14/2013

J. D. Johnnie, a Chinese, tries to murder his ex-wife, Christine O'Reilly, in Vancouver 1/14/2013

The deathof Mong Fong 2/6/2013

The death of Emmie Brienne 2/6/2013

Early Chinese-White Marriages in North America

Who Were the White Wives? 嫁华人西妇 – 何许人也?

The American press tended to assume that most white girls who married a Chinese man were forced to do so by poverty. And indeed, many girls clearly were motivated at least partly by a desire for money. As a Chicago journalist noted in connection with the murder trial of Alice Sing (see below), poor white girls “were lured into [Chinese men’s] parlors, stores, and chop suey joints by their pleadings and outward gentleness, then, captivated by the apparent luxury of their lives and apartments, they visit them again and again until their ruin is accomplished.”

A typical story is that of the marriage of Charles Guy, a chef at the Lincoln Hotel in Los Angeles, to Rachel Beaver, who as "a 16-year-old miss, whose stepfather and mother were very poor and had quite a brood of little ones to look after, used to call at the Hotel Lincoln for assistance in the way of victuals. In this way Guey became acquainted with Rachel and pretty soon became infatuated with the little damsel. . .

"Miss Rachel Beaver had got heartily tired of everlasting poverty, in a tent, and she greedily took the matrimonial bait held out by Charley. . . But Rachel was not yet 16, and he was a Chinese. Miscegenation is not permitted in this state. Thus things looked rather glum for the lovers, although Rachel's mamma had no objection in the world against such a union."

The solution, it turned out, was for Charles and Rachel to be married by the captain of a boat "on the high seas." The couple returned to land and, although annoyed by the constant panhandling of Charley's new in-laws, lived happily "for a long time" afterward. (Los Angeles Herald 1897-12-14)

Quite a different sort of marriage is sketched in this newspaper story about a couple in Seattle:

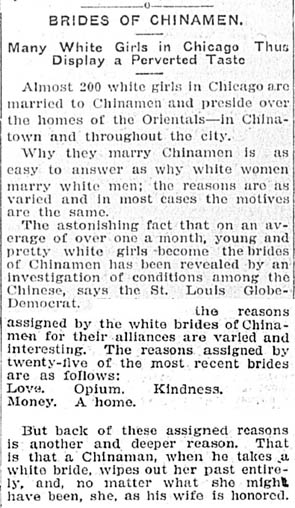

Wah Lee, a former Christian missionary among the Chinese of St. Louis and a Yale graduate, was married last evening to Miss Jessie Ward, the daughter of a former Kansas City manufacturer, Wah Lee has abandoned all his oriental traditions and is known as William Head. While still prominent in church work among his countrymen, Mr. Head finds time to manage a lucrative tea and dry goods business. . . Minneapolis Journal 1902-02-15

image from Seattle Times 1902-02-06

Another story:

"Edith Burnett, a tall, comely English girl and John Toy, a Chinese rancher of Yakima, were joined in wedlock last night by Rev.H. D. Brown. . .

"From assertions made by acquaintances and from the actions of the woman herself, the marriage has the appearance of a business transaction on the part of both man and wife. Before uttering the words which would make her a wife, Edith Burnett called the minister aside, showed him an note for $400, signed over to her by Toy, and asked him if it was any good." Spokane Press 1903-02-20

"John Toy, the Chinese bridegroom of a day, who was married to Miss Edith Burnett, a white girl, on Wednesday evening, yesterday left his spouse in this city and returned to North Yakima, where he is said to own a valuable farm and considerable cash. Seattle Times 1903-02-20

"Edith Burnett, who married Jung Toy, a Chinese hop-grower of the Yakima Valley . . . obtained a divorce today through Judge Rudkin at North Yakima. . . She alleges that he was intolerable as a husband . . . that he attempted to make her eat dried rats. . ." San Francisco Chronicle 1903-03-26

And genuine love seems to have often motivated white girls to marry Chinese husbands, whether or not one spouse was richer or higher in social status.than the other

"About three years ago Hedwig Brossak, a pretty and educated white girl, surprised San Francisco by marrying Ngui Lee, a Chinese cook. Mrs. Lee retired into the privacy of Chinatown, and everyone predicted that her life would henceforth be a burden to her.

"The young woman, however, still retains her infatuation for Ngui, She lives in two little rooms at the top of a big tenement on Washington Street. . . they are an oasis of neatness and cleanliness in the midst of Chinatown, and Hedwig says that she is very, very happy." San Francisco Call 1895-06-27

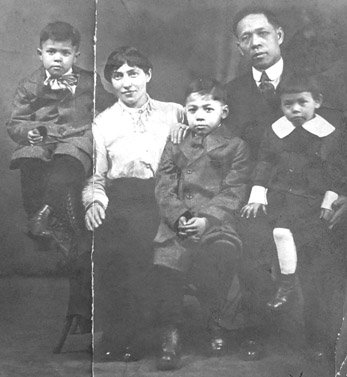

White Wives and Their Mixed-Race Children 西妇与半唐番子女

Photographs of European American wives of Chinese American men tend to reinforce one's impression that many such mixed marriages were as successful as any others, and that both wives and husbands cared deeply for their interracial families.

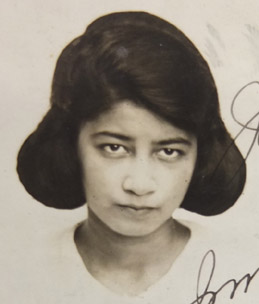

1941 Genevieve Louie, Minneapolis

NARA Exclusion Files photo

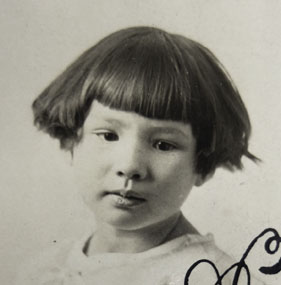

1932 May Wong, Chicago. NARA

Exclusion Files photo

Born 1916, Chicago. Father: Wong Shu Tong/ Joe Wong, b. 1885 in SF, restaurant manager, Mother: Sofie Szcrepanek, b. Poland in 1898. I 1932, May was to be taken to China by her father with her brother Edward.

Also Louie Yip Moy, born 1920. Mother: Lena Wjcik or Wujcik, born in Buczacz, Poland. Father: Gann Louie or Louie Shear Gim, waiter in Nanking Restaurant, Minneapolis, born in Hoy San, Gung Sai Village, "Hoy San District formerly known as Sun Ning District". Lena and Gann had 6 children: , Lowell Gerard, and Neree. Grandfather: Louie Gar Hip, merchant at 316 Yesler Way, Seattle. Genevieve applied to go to China in 1941.

(or Lotty Kopski), born in Germany (?) Remarried in 1911 to George Der Wing, restaurant owner in Chicago (came to US in 1879, born in Seung/Shung Keow Village, Sun Ning. Also a remarriage: 1st marriage to Wong Shee in 1895; she died. Children (all by Lotty and surnamed Der Wingson) = Joseph (10), George (9); Mary (7), & Sylvia (5)

Born ca. 1890 in Poland (then Austria). Husband: U.S.-born Chin Tong, son of Chin Mon Quong, a druggist in Seattle. In the mid 1900s, Chin Tong was secretary to Kang You Wei but now is an interpreter, headwaiter, etc., in Chicago Mother of Mike or Estener (8), George (6) & Christopher (4).

Lotty Barbery Kubska & family, 1924

NARA Exclusion Files photo

Anna Bonick & family, ca. 1917

NARA Exclusion Files photo

The following section shows more evidence that Chinese-white marriages in the U.S., or at least in the eastern U.S., often were successful. Many seem to have been as successful as white-white or Chinese-Chinese marriages.

Mary Der Wingson, 1924, Chicago

NARA Exclusion Files photo

Catherine Hue, 1921, Minneapolis.

NARA Exclusion Files photo

Grace Wong, 1921, Chicago

NARA Exclusion Files photo

Born 1906. Father Charlie Lee/ Lew Tai Ho, laundryman, Chicago. Mother Minnie Kay (daughter of Jacob Kay, a German). Stepfather Wong Wing/ Wong Hop, formerly of Deadwood, now Chicago. Minnie died 1920. In 1921 Wong Wing planned to take his own 2 children plus Grace back to China “to learn Chinese.”

Born 1917. Mother: Lotty Kubska. See above in this section

Born 1912. Mother: Beatrice Pauline Polmatin, born in Westfield, MA. Father: Charles Hot Hue/ Charley Wong/ Yip Art Hue/ Yep Wong, born in China and, in 1921, a restaurant owner in Minneapolis. He planned to sent Catherine

Adult Daughters of Mixed Marriages

Younger Daughters of Mixed Marriages

Families of Mixed Marriages

Defending Mixed Marriages 异族通婚. 有何不可

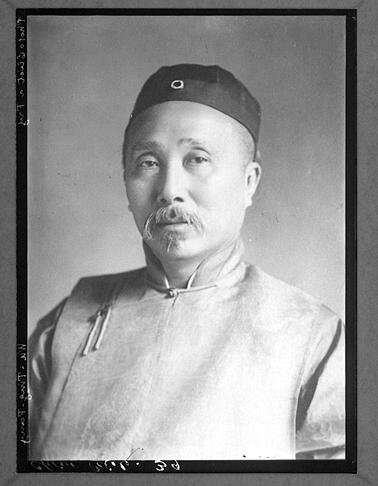

Against a chorus of racist warnings about the perils of miscegenation, a few voices spoke up in defense of Chinese-white intermarriage. One such voice was that of the great Wu Ting Fang, Chinese Minister [Ambassador] to the U.S. Replying to criticism that in a newspaper interview he had advocated changing American laws against intermarriage (which he may well have done), he said he had "told the reporter that in China the half-castes had the brightest children and that the marriage of white people to Chinese was regarded favorably. . ." but that "he made no remarks about the race question beyond that and, with his knowledge of American customs, would not presume for an instant to advise us in such a matter." Minneapolis Journal 1901-02-15

Wu Ting Fang 伍廷芳

ca. 1900. from Wikimedia Commons

A similar opinion was voiced by a Hawaiian newspaper a few years later: "In California the Chinaman is treated as an outcast, a pariah; here he is treated as a fellow human being. The California Chinese acts like an Ishmaelite; the Hawaiian Chinese acts like a man among men, self-respecting and, according to his lights, decent, law-abiding, and public-spirited, No native population in the world would be finer than ours if the Hawaiians were to merge with people like his." Hawaiian Gazette 1906-01-26

Agnes T. Anderson with 3 of 4 children, Chicago, 1913. Born in Sweden, 1878. Married in 1897 to Harley T. Moy, native of Sunning (Taishan) China. The tallest child is Helen, born 1901 in Lowell, IN. NARA Exclusion Files photo

Success Stories: Committed Husbands, Resourceful Wives

成功例子: 钟情夫婿. 善舞妻

Disastrous East-West marriages, naturally, got more publicity. But many were successful. Early newspapers and books rarely mentioned stable, contented Chinese-Caucasian couples. A few, however, did make their way into print. Among the more notable were the Charles Yip Quongs of Vancouver and the Wong Sun Yues of San Francisco. The latter marriage ended sadly but gained much favorable publicity in earlier years.

Charles Yip Quong & Nellie Towers

Wong Sun Yue and Ella May Clemmons

Charles Yip was a Vancouver businessman and a nephew (actually, a cousin once removed) of Yip Sang, the dominant figure in Vancouver's Chinatown in the 1890s-1900s. Nellie Towers was a teacher from Nova Scotia. The two married in Boston in1900 and moved to Vancouver in 1900. There, Nellie, an accomplished linguist, served as a midwife to much of the local Chinese population and as an articulate advocate for Chinese Canadian rights.

Wong Sun Yue's business was wiped out by the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. It was as a refugee from the destruction that he met and married Ella May Clemmons, a wealthy Californian missionary who spoke several Chinese dialects. Ella worked hard and effectively for the Chinese community, living happily enough with Sun Yue until 1922, when she discovered he had another wife in China.

Note:The photo of Charles and Nellie Yip appears on several websites (e.g., historywalksinvancouver.blog & househistorian. blogspot.com) and in Paul Yee's Saltwater City. We do not know who owns the copyright. The photo of Sun Yue and Ella Wong is from a postcard in a private collection; postcards depicting this couple are quite common and exist in multiple copies.

Click here for Larry Wong's essay on Nellie, presented at a University of British Colombia conference in 2012 and now published here on the CINARC website.

Click here to link to Patrick Lozada's pioneering biography of Ella, written as a senior honors thesis in 2011 for Bryn Mawr University.

White Girl in Chicago Displays "Perverted Taste," in 1929.

Sonya Gertrude Netzell (born1906 in Chicago). Husband: Lim Kho Beng or Francis Lim (born 1900 in Singapore), married in Crown Point (IN) in 1926. Two reasons for marriage: Margaret Frances Lim (b 1927, on left) and Janet Grace Lim (b 1929, on right). Her husband entered the U.S. as a student and now was taking Sonya and the girls with him to China. His brother, Dr. Robert K. S. Lim, was at Union Medical College, Peking.

Sonya with Margaret. .NARA Exclusion Files photo

Sonya with Janet

Why Did Chinese- and European-Americans Intermarry?

中美为何要通婚?

Unsuccessful Intermarriage: Murders from Jealousy and Posessiveness

不成功例子: 妒嫉 -谋杀

In mixed East-West relationships, neither Chinese nor whites were immune to deadly emotional crises stemming from withdrawn or unrequited love. The two cases reported here are typical. The psychological causes involved are not essentially different from those behind many Chinese-on-Chinese and white-on-white crimes.

Unsuccessful Intermarriage: Suicides from Jealousy and Posessiveness

Withdrawn or unrequited love in East-West relationships resulted in suicides, perhaps more often than murders. Here too, the psychological causes of such tragic actions are not confined to particular cultures. Shakespeare's famous epigram, “Men have died from time to time, and worms have eaten them, but not for love,” was true neither for European not Chinese cultures. In both, sadly, self-killing from love had long existed by the time Chinese came to this continent and became emotionally involved with non-Chinese.

The Death of Mong Fong

"Mong Fong was a Chinaman who came some years ago to Chicago, where in 1876 I became acquainted with him as a witness in a law case. He was a tall fine looking fellow and had sacrificed his pig tail, and in fact had adopted American dress and manners as far as he could, probably fondly imagining that no one could distinguish him from men not Mongolians. At that time he was employed by a well known manufacturing firm and had by industry, honesty, intelligence, and thrift worked his way up into a position of some trust. He had also obtained some education and wrote his name for me both in Chinese and English, which autograph I have now before me. He evidently had some of the best and brightest attributes of manliness in him. Mong Fong fell in love with an American woman and was accepted by her, whether in joke or earnest I know not, and the day was set for their marriage. The poor fellow boasted of his happiness and, after the manner of his own country, made sundry presents to his friends and fellow workmen and invited them to the wedding feast. The day came and the hour came and passed but the promised bride did not come. Either her friends had laughed or scared her out of the idea, or else she had all along been accepting the stranger's presents and attentions only by way of a joke. However this may have been, it was no joke for the luckless Mong Fong. He could not bear to face the disappointment and the ridicule to which his mistake must expose him. He went to his lonely room, locked his door, lay down on his bed, and shot himself. A mound in the Potter's Field was his only monument, and a jocular paragraph in next morning's papers his only epitaph.

"So went out his gentle, inoffensive, hopeful, useful life. . ."

Joseph Kirkland, "The Chinese Question," The Dial, March 1881, p 235-6

The Death of Emmie Brienne

"My Dear Sing:

Almost everyone does me an injustice and tells lies about me because I have too much consideration for you. For this reason I want to die, but you are not responsible for my doing so. I have given part of my things to the poor. Please take care of my body. I do not owe a cent to anybody except Mrs. Smith on Hyde Street, for burning extra gas.

"I must leave you now, with many thanks, as you have been extremely kind to me. With tears I will say good-by, as you are the only one that I regret to leave in this world. I hope God will forgive me for taking my life, and you, Sing, take good care of yourself: don’t worry about me. Goodbye, sweetheart.

"Very Truly Yours"

(Signed)

“Emmie”

“Emmie”

Hong Sing was a cook for a San Francisco family. She was a servant. “She asserted that Hong Sing had promised to marry her, but he denies that he ever gave such a promise.”

Seattle Times 1903-06-28.

The editors first encountered the story of the Sings in Northwestern University's on-line historical files on Chicago murders: http://homicide.northwestern.edu/. Most of the above comes from contemporary newspaper accounts of the murder found in the microfilm newspaper archives of the Harold Washington branch of the Chicago Public Library. The following newspapers covered the Sing case: the Chicago American (9/5/13-9/13/13), the Chicago Daily News (9/8/13-9/9/13) and the Chicago Evening Post (9/4/13). This article was originally written by the editors for the website of the Chinese American Museum of Chicago. A version without the photograph may be found at http://www.ccamuseum.org/index.php/en/research/research-1900-1949/119-1913-bad-east-west-marriages-ii-alice-davis-sing-murders-charles-sing

Still more cases: In 1920 in Boise (Idaho), Ruth Bowers, a "little Chinese girl, was granted a divorce from her white husband, Alfred Bowers." Six months later, "Sammy Fong and Ruth Bowers, members of the local Chinese colony, were married. . . by Judge D. T. Miller of the probate court. The bride is actively connected with the W.Y.C.A. [Young Women's Christian Association] of this city [Boise]." Idaho Statesman 5/23/1920; 12-07-1920, p 5

Bowers was a local man, and the Statesman implies that Ruth (her maiden name was not given) was a local resident as well. Whether intermarriage in Idaho was completely illegal at that time is uncertain, but inter-divorce seems to have been all right with Idaho courts. It is interesting that Ruth seems to have divorced a European-American in order to marry a Chinese-American. China Mary (see above) did the opposite.

And it was not only poor white girls who married rich Chinese. The reverse, poor white men marrying rich Chinese girls, happened too. For instance, in 1916, William Wyatt, a chauffeur from Tulare, California, left for Ensenada, Mexico, in order to marry Daisy Joe, an American-born Chinese woman. "It is reported that Wyatt will be paid $5000 by Miss Joe's father, a wealthy San Francisco merchant, if the ceremony is performed." Idaho Statesman 1916-10-05

Wikipedia's Statistics on Chinese Interracial Marriage in the U.S.

维基百度网上的中美联婚数字

. . . in 1880, the tenth US Census of Louisiana alone counted 57% of interracial marriages between these Chinese Americans to be with African Americans and 43% to be with European American women. Between 20 and 30 percent of the Chinese who lived in Mississippi married black women before 1940. In mid 1850s, 70 to 150 Chinese were living in New York City and 11 of them married Irish women. In 1906 the New York Times (6 August) reported that 300 white women (Irish American) were married to Chinese men in New York, with many more cohabited. In 1900, based on Liang research, of the 120,000 men in more than 20 Chinese communities in the United States, he estimated that one out of every twenty Chinese men (Cantonese) was married to white women.

The current (as of February 2013) "Miscegenation" article on the Wikipedia website offers these statistics on early Chinese men intermarrying with women of other races:

Now, we have no quarrel with the data on Louisiana and Mississippi. Intermarriage in those states of Chinese with both blacks and whites is attested by highly credible census statistics. And the mid-1850s New York data also seems believable enough (see the preceding article).

But we have problems with the idea that 300 white women were married to Chinese in New York in 1906, or that one in twenty Chinese men in the U.S. had white wives. The 1906 figure comes from an article about an impending (and never implemented) move of Chinatown from Manhattan to Brooklyn. The article reads: "In this city, it is said, there are 300 American women, it is said, who are the wives of Chinamen." It goes on to say, however, that only 60 live in Chinatown with the rest somewhere else in the city (Note 1). Similar totals appear nowhere else and seem to be only a Times reporter's informant's guesses.

We find it easier to believe that Liang was making a rhetorical point rather than reporting a statistical fact. Generally critical of Chinese Americans, on one occasion he commented that some had married American women, "and thus their sense of Chinese patriotism had faded." (Note 2) As this threatened support for his program of radical reform in China, he may have been exaggerating the intermarriage problem in order to instill a sense of urgency in his readers.

Note 1. New York Times 1906-08-06, p 14

Note 2. K Scott Wong (1996), in Lucy Maddox ed., Locating American Studies: The Evolution of a Discipline,

We have even more problems with the notion that in 1900 one out of every twenty American Chinese men had white wives. The statistic comes from Observations on a Trip to America 新大陆游记 (1903) by Liang Qichao 梁启超:

"There are more [Chinese] women and children on the West Coast than on the East Coast. But in America, most Chinese try to make a living and then to return [to China], which is quite different from those [Chinese] in Hawaii and Southeast Asia. Because so few familes are here, those who marry western women are approximately one in twenty. . . I estimate that there are not more than 120,000 Chinese in America." [editors' translation]

A founder of the Baohuanghui, brilliant intellectual, and keen observer, Liang's opinions must be taken seriously. However,his figures seem to us incredible. According to the1900 U.S. Census, half of all American Chinese (45,000 of

Liang Qichao, 1901 from Wikipedia

"The Pacific Railway Complete" == Satirical (and racist) cartoon from Harper's Weekly 1869-06-12

The threat ot interracial romance when the first transcontinental railroad was complete and West Coast Chinese began coming east, 1869. Harper's Weekly, 1869-06-12

90,000) lived in California, and almost a quarter of the rest (10,000 of 45,000) were in Oregon. If Liang's figures are valid, this would mean that in 1900 there were 2,750 white Chinese wives in those two states. But neither state permitted Chinese-white weddings to be performed within their borders. The same was true of Arizona, Nevada, Idaho, and Utah. Some couples could have gone elsewhere to be married: to Washington, Canada, Mexico, or on the high seas beyond state jurisdiction . But so many? When West Coast newspapers still treated such marriages as interesting novelties and yet never reported more than ten or twenty in any one year?

Data from ancestry.com throws more light on Ruth Bowers' divorce and remarriage. Her maiden name was Wong Ah Toy or Wong Shee. She arrived in Vancouver via the Canadian Pacific ship Empress of Russia in 1914. The passenger list gave her name as Wong Ah Toy or Mrs. Alfred Bowers. She evidently was already married, or at least engaged, to Bowers. How he met or arranged a marriage with Wong Ah Toy is a mystery. Born in 1891 and previously mentioned only once or twice in the Statesman, which as Boise's leading newspaper kept close track of prominent local citizens, Alfred Mills Bowers does not seem to have been particularly rich or well-traveled. But then how did he come to have a bride imported by him directly from China? And how could that bride have acculturated so rapidly that she became active in Boise's YWCA only six years after her arrival in North America?

The Sam Fong who became Ruth/ Ah Toy's second husband is probably the one listed in the 1920 Census as having been born in China and residing in Ada, Idaho. The marriage book of Ada County (vol. 16, p 137) confirms that he married Ruth Barnes on December 6, 1920. Was Sam Fong unusually rich or charming? Did Alfred Bowers turn out to be a bad husband? We do not know. [Note 6]

Fong See, Letticie Pruett, and Family

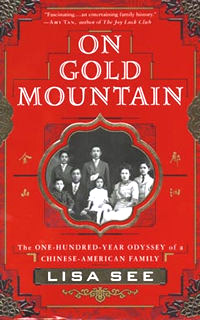

Among the most famous of all such marriages was that of Fong See, vividly described in a memoir by Fong See's great-grandaughter, the well-known novelist Lisa See.

Wikipedia summarizes the plot: "The memoir centers on Fong See, the author’s great grandfather and his second wife, Letticie Pruett (Ticie). Fong See was one of the few who realized the dream of coming to the U.S. and finding "Gold Mountain".[4] So many others left China with the same dream but ended up with their dreams shattered. Fong See, the family patriarch, became the richest man in Chinatown and was recognized by the powers of Los Angeles proper. In China he had even more influence as "Gold Mountain See". Although Ticie was a perfect partner for Fong See in helping him develop his growing number of stores and being the proud mother of many of his children, in the end their marriage was destroyed. Keenly aware of his wealth and influence, as Fong See grew older he felt that the Chinese view of men's superiority to women was correct. In marrying a 16-year old Chinese girl, he found what he wanted—the perfect wife in her complete subservience to her husband. Ticie’s love for Fong See was so strong, that after her separation from her husband, she gradually fell apart." [Note 1]

Click here for an enlargement of the cover photo, taken in 1910 and showing Fong See, Letticie Pruett, and their children, Eddie, Sissee, Bennie, Ray, and Ming. The editors hope to get permission to use the enlargement; until then it will appear with a diagonal bar across it.

On Gold Mountain: The One-Hundred-Year Odyssey of My Chinese-American Family. Lisa See, St. Martins Press, 1995; Knopf Doubleday, 1996 & 2012

The relationship of Letticie Pruett and Fong See followed a common path for early East-West marriages in America in being economically hypergamous, with a poor white girl marrying a richer Chinese man.

In Lisa See's words, "By the late 1890s, after years of manual labor, Fong See owned the Curiosity Bizarre, which manufactured underwear for brothels. Letticie had run away from home and ended up in Sacramento. When no one would hire a single, uneducated woman, she drifted into Chinatown and the Curiosity Bizarre, where she begged Fong See for a job. He hired her, one thing led to another, and they decided to get married." [Note 2]

Letticie's and Fong See's marriage differed from many other hypergamous white-Chinese marriages in that the wife turned out to be an excellent businesswoman who played a key role in the growth of the husband's business. However. their marriage was similar to other North American Chinese marriages in one important respect: the husband, from a background where polygamy was the right of all successful men, seems not to have hesitated to take a second (or third?) wife during a visit to China. White wives such as Letticie, like American-born Chinese wives in similar situations (for instance, Seattle's Dong Oy in 1909), felt profoundly betrayed by such behavior.

Did Fong See realize that California's community property laws, which had been in force ever since the 1850s, meant that he would forfeit half of his possessions by abandoning Letticie? [Note 3] Perhaps not, but one suspects he learned later that he had made a serious mistake.

Note 1. Wikipedia, "On Gold Mountain" article (as of February 2013).

Note 2. Lisa See, "Stuck in the Middle," Time Magazine, Apr. 23, 2001

Note 3. Section 1386 of the California Civil Code, in William M Mckinney ed., 1922, California Jurisprudence: A Complete Statement of the Law and Practice of the State Of California, Vol 5

Mixed-Race Children as a Cultural Bridge: The Kim Loo Sisters

Thanks to Leslie Li and Jane Leung Larson, we now know quite a lot about one of the outstanding cases of Sino-European daughters who helped to bridge the cultural gap between East and West. There had been a good many before, including the novelists Han Suyin and Sin Siu Far. But until after World War II, few managed to walk the intercultural/interracial tightrope with more success than the Kim Loo Sisters, the Kimmies.

One of the four, Genevieve Louie, is featured in in the preceding article. In the 1930s, using the name Jenée, she and three of her sisters, Alice, Maggie (Margaret), and Bubbles (Patricia) formed a singing group called after their father, Gann Louie (Immigration spelled it "Louis") or Kim Lo. The group was a success, appearing in vaudeville performances in many places, including Broadway in New York where they "shared top billing with such stars as Frank Sinatra, Jackie Gleason and Ann Miller" (Note 1). Leslie Li, Jenée's daughter is in the process of producing a documentary film about the group. A trailer/preview of the film can be viewed on YouTube (Note 2).

The Kimmies in 1938-9, publicity photo. Credit: James Kriegsmann

Note 2: http://youtu.be/gM9KpAIlYUo

Singing groups in those days, unlike certain of their modern peers, sometimes lived healthy lives. The following photograph, also from Leslie Li's blog (Note 3), shows that all four were still in hale and hearty shape as of four years ago. From left to right: Jenée (87), Alica (91), Maggie (89), and Bubbles (85). Bubbles was the lead singer.

The Kimmies in 2009. Credit: Leslie Li (Note 3)