| ||||

| ||||

Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee (CINARC)

CHINESE LABOR 各行各业

This page focuses on the ways that ordinary Chinese earned a living in the Northwest. In the United States, though not in Canada, the distinction between "laborer" and "merchant" was of great importance in terms of immigration law. Laborers -- defined as persons who worked with their hands -- were much more likely to be refused readmittance when they went back to China to see their families, and after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, no laborer could hope to bring his wife into the country. In Canada, entry rights depended more on wealth than on class. Until the 1920s, you could enter Canada and bring your family too as long as you could pay the head tax for yourself and each person with you.

Chinese miners, farmers, fishermen. and laundrymen were classified as laborers but tended to work for themselves or in small cooperatives. Some of them earned good livings. Those in other jobs had fewer prospects and often were poor. The main hope for Chinese trapped in such jobs was to save enough to start businesses of their own.

The page was begun on April 25,1911 and is still far from complete

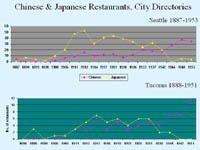

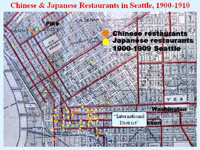

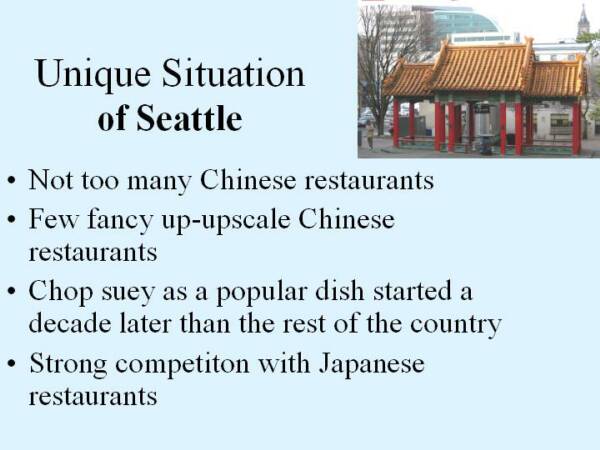

As in other cities, chop suey was the main attraction

Seattle was different. Chinese restaurants were less popular.

Even at the height of the boom, Japanese competed effectively

Japanese restaurants outnum-

bered Chinese restaurants

But restaurants were important to local Chinese anyway

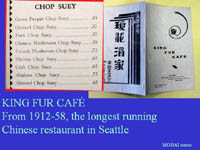

King Fur Cafe was one of the longest-running

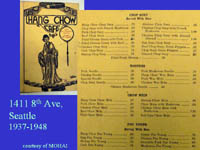

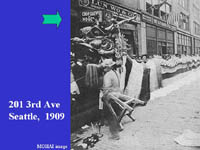

Many Chinese restaurants like this one were in Chinatown

They provided work for many Chinese Americans

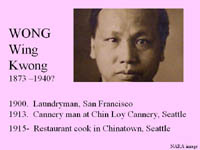

And for some, a chance to get ahead

At least in the eyes of non-Chinese diners

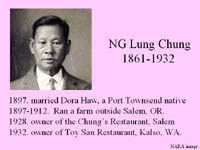

What about the rest of the Northwest? BC was not the same

Even though it had chop suey too - in Quesnel. for instance

And anti-Chinese prejudice was still strong in places like Tacoma

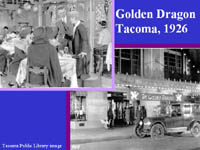

This Tacoma restaurant was not a real one: instead, a movie set

We still don't know much about other Northwest places.

If you know about old Chinese restaurants and/or chop suey in those places, please let us know. Just click on "comments" to leave a message

Chinese Restaurants and Chop Suey in the Pacific Northwest 西北角早期杂碎餐馆

Restaurants 餐馆业

Does a Chinaman do your washing? 替你洗烫的是中国人吗?

“Does a Chinaman do your washing? If so you're not carrying out the principles of unionism.” Seattle Union Record

January 20,1906.

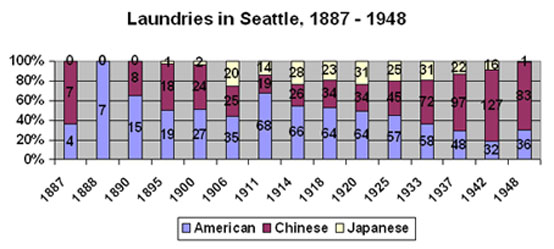

In 1906 Seattle residents with soiled clothes had a choice of laundries. Followers of union opinion, as expressed by the Knights of Labor in their newspaper, could have patronized any of the 35 American laundries in town. They could also have tried one of 20 Japanese laundries, which the Knights seem not to have placed on their blacklist yet. Or they could have defied the union and, like many Americans elsewhere, taken their clothes to a Chinese laundry anyway. There were 25 of those.

Ten years earlier, the Seattle Chapter of the Knights may have thought they had permanently cleared out all Chinese workers, including laundrymen. Through an orchestrated effort culminating in the January 1887 anti-Chinese riots, they closed down every Chinese laundry in the city. The Polk's city business directory for 1887, compiled before the riots, listed 7 out of the 11 laundries in Seattle as Chinese. However, in the 1888 directory, Chinese laundries had vanished. All surviving laundries, as required by union principles, were white.

This situation did not last. Seattle’s next decade saw a big rise of population and dressing standards, and hence of dirty shirts that needed the washing, starching, and ironing skills of hand laundrymen. So, in spite of labor opposition, the Chinese came back. Between 1890 and 1900 not only did the number of laundries in the city double, but almost half were run by Chinamen. There were also already a few run by Japanese. To fanatic white racists this must have seemed an ominous development.

The editors of Polk’s Directory for Seattle had a hard time deciding how to handle Asian ethnic laundries. Early editions always listed Chinese laundries separately from “mainstream” laundries, except immediately after the 1886 riot when there were no Chinese laundries to list. In 1892, when ethnic laundries again appeared as a separate category, Chinese and Japanese laundries were lumped together as “Chinese laundries”. In 1895 the Japanese were moved from the Chinese category to the mainstream, European-American one. They stayed there until 1906 when the Directory’s compilers, perhaps aware that the Knights and their supporters did not regard Japanese as honorary whites, chose to join both kinds of Asian laundries in a new separate category, “Chinese and Japanese.” It was not until the late 1940s that all laundries were listed as one category, specifying Chinese and Japanese in brackets after their laundry names.

Were the Chinese laundries singled out solely for racist reasons or because they also offered a different kind of service? Did Native Americans or African-Americans operate laundries at that time? Did Japanese and Chinese laundrymen regard each other as competitors or as allies? Why did the percentage of both kinds of ethnic laundries decline in 1910 for a few years? Why did Japanese laundries, which tended to be bigger than the Chinese kind, begin to decline in number as early as the 1930s?

(Data from Polk's and other city directories)

Chinese Laundry, San Francisco, ca. 1880

Laundries 衣裳馆

Chinese Fishing in Washington Territory

Like most students of Chinese America, the present editors were aware that Chinese had been fishermen, as well as fish cannery workers, in California and British Columbia in the19th century . However, we had believed that, due to the opposition of white fishermen, no Chinese at all had engaged in professional fishing in either Oregon or Washington. Hence we doubted Grant Keddie, archaeology curator at rhe Royal British Columbia Museum, when he told us that there once had been Chinese fishermen at Port Madison on Bainbridge Island, across Puget Sound from Seattle.

He was right and we were wrong. The relevant source is George Brown Goode's classic Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States (1887, Part 2, Sect 4, p 47):

"In Washington Territory there are thirty-three Chinamen engaged in fishing. About Cape Flattery and Quartermaster's Harbor there are twelve. Near Port Madison there are fifteen engaged in drying fish. They also buy from the Indians. Especial value is set upon flounders but salmon are held by them in small esteem. At Port Gamble and Ludlow there are six Chinamen who occupy their time in fishing from the wharves. They catch a large quantity of dogfish."

Were Chinese fishermen environmentally irresponsible?

And a last item from George Goode, reminiscent of the current campaign against the gill nets used by Korean and other Asian fishermen. Then as now, spokesmen for the U.S. fishing industry were claiming that only unscrupulous foreigners would use such devices. Goode (see the two preceding items) quotes the Antioch (California) Ledger, July 6 1876:

According to the Kitsap Country Historical Society, the special census of 1883 counted about twenty Chinese at Port Madison who "worked as laundrymen, fishermen, and cooks." (http://www.secstate.wa.gov/history/cities_detail.aspx?i=35)

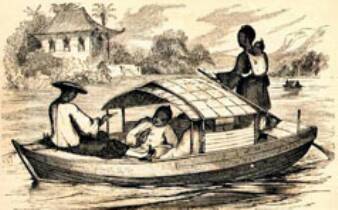

Chinese shrimp fishermen in San Fran-

cisco Bay, Harpers Wkly 20 Mar 1875

Were those fishermen Tankas?

There were a lot of Chinese fishermen in California during the late 19th century: Jack Chen estimates that there were as many as 2000, living in 28+ villages scattered from Tomales Bay in the north to San Diego in the south. The main reason why no such villages existed north of the Oregon border is that white Northwesterners regularly threatened death to any Chinese who dared to fish in their waters.

"At Punta Alones and Pescadero the Chinese fishermen carry on a fishery for the capture of surf fish (Embiotoca lateralis, Damalichthys vacca &c), and their methods, being characteristically oriental, are of much interest to a stranger The gill nets are placed among the kelp-covered rocks not far from shore and the boat goes around among the nets to frighten the fish into them. The old man plies the oar sculling the boat. The young man stands in the bow with a long pole which be throws into the water at such an angle that it returns to him. The woman sits in the middle of the boat with the baby strapped on her back. She is armed with two drum sticks with which she keeps up an infernal racket by hammering on the seat in front of her. This is supposed to frighten the fish so that they frantically plunge into the nets. Occasionally this is varied by the woman taking the oar and the old man the drum sticks."

As everyone who has seen Hollywood movies about Hong Kong during the British period knows, traditional Tanka women often sculled boats themselves, many with babies strapped on their backs.

Does this mean that at least some of the 19th century immigrants to California were Tankas? Perhaps. It is not easy to imagine an ordinary southern Chinese woman of that period sculling a boat, with or without a baby on her back.

Linda Bentz and Robert Schwemmer, "The Rise and Fall of the Chinese Fisheries in California." In Susie Lan Cassel, ed., The Chinese

in America, pp 140-155. Altamira Press, 2002.

Jack Chen, The Chinese of America, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1980

Thomas W. Chinn, H. Mark Lai, and Philip Choy, A History of the Chinese in California, A Syllabus. San Francisco: Chinese Historical

Society of America, 1969: pp 36-40

George Brown Goode, Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States, Section IV. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1887

Considering that (1) so many California Chinese made their living by fishing and that (2) virtually all salt-water fishermen in Guangdong province at that time were Tankas (Pinyin: Danjia), members of an outcast community who lived on boats or in specialized fishing villages, it makes sense to ask, were the California fishermen also Tankas? Or were they former farmers or tradesmen who learned to fish after coming to America?

In 1887, Goode (pp 37-41) offered useful descriptions of Chinese boats and fishing methods. The boats used by shrimpers in San Francisco Bay were greatly inferior, in Goode's view, to those used in southern China Coast. He describes them as "long, unwieldy, clumsily-constructed craft," much less seaworthy than those used on the other side of the Pacific "The Chinese fisherman of China is very different from the Chinese fisherman of California and far above him in equipments, habits, and scale of work. Confident in his seamanship and skill, he dashes around in his lateen-sailed junk in a reckless manner, ...while the latter tugs painfully at his oar."

This may indicate that the California fishermen did not come from a fishing background in China and, hence, that they were not Tankas. And yet a couple of Goode's descriptions make one wonder. One is of fishermen near San Diego, some of whom "live entirely on their boats, visiting their houses on land perhaps once a month." That sounds like Tankas. So does the following description of fishing families, which Goode quotes from a Professor Jordan:

Tanka woman in China, sculling boat with baby on back. From Ballou's Pictorial, 1855

Chinese fishing in Washington Territory [11/10/09]

Were Chinese fishermen irresponsible about the environment? [11/10/09; updated 02/08/10]]

Were those fishermen Tankas? [05/11/11, updated 04/19/2012

Fishermen 渔业

"WORSE THAN SEA LIONS. Our legislature has attempted to protect the salmon in our rivers by repealing the law protecting seals. It is asserted that the seals destroy the salmon which come down annually from the upper rivers to salt water. This may be true but opinions are conflicting. However that may be, there is an enemy to the salmon far more dangerous than the round eyed seal, and that is the busy Chinaman. Only a few days since, we watched the modus operandi of catching fish in our San Joaquin [River]. Two Chinese junks or schooners appeared in the river, each holding an end of a remarkably fine net. The schooners then separate and sweep the waters with the net to the shore. Fish of all sizes are thus caught and none. not the smallest salmon trout, are ever returned to the water. Those too small for market are thrown on the shore or fed to poultry. It is said by those familiar with the Chinaman's mode of fishing that these fine nets leave no young salmon behind and are far greater enemies to their propagation than seals." (Goode 1887: p 47)

One of the best decriptions of an early Chinese-American fishing community is in a short story, William Henry Bishop's "Choy Susan" (Atlantic Monthly, August 1885, pp 256-263), about ocean fishermen near Monterey in California. The story is also notable because its heroine, Choy Susan, may be the first fictional Chinese-American woman to have been depicted not as a hapless victim but as a strong, intelligent, and capable person.

Chinese Fishing Boats off San Francisco, from Harpers Magazine 1883

A Later Note:

Bentz and Schwemmer (2002:150-2) cite several other historians who agree that early Chinese fishermen in California must have learned their trade back in China. None, however, suggest that Tankas may have been involved. The main question is whether there were fishermen in coastal Guangdong who were not Tankas, contrary to what many believe, and whether these non-Tanka fishermen could have migrated to California in the 1850s-1870s.

Philip Choy informs us that the last surviving shrimp fishermen at China Camp (on Point San Pedro in San Francisco Bay) considered himself to be an ordinary California Chinese and that he would have denied he had Tanka ancestors.

Railroad Workers 铁路业

The role of Chinese labor in building the transcontinental railroads forms a central theme in writings about Chinese North American history. Such writings usually emphasize the cost in Chinese lives, the fact that the Chinese received little credit for their efforts, and that they were abandoned by their employers as soon as the work was done.

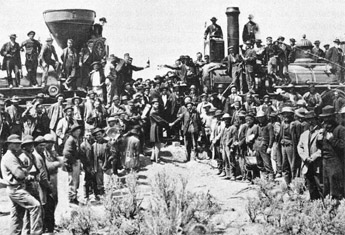

"1869: The Transcontinental Railroad is completed. About one in ten Chinese workers have died building the railroads — 1,756 miles of track have been laid at the cost of 1.7 Chinese deaths per mile — leaving about 12,000 still employed at this point. Hundreds of railroad men gather to have their picture taken at a ceremony in Promontory Point in Utah, on May 10, when Stanford lays the final “golden” spike. But the Chinese who comprised the majority of the work force are excluded from the ceremonies entirely." (http://www.zakkeith.com/articles,blogs,forums/anti-Chinese-persecution-in-the-USA-history-timeline.htm)

We do not propose to go deeply into all these subjects here. As is pointed out further down on this page, we agree that Chinese got little credit for their work. On the other hand, we feel we must address the notions that this work meant a horrifying loss of life and that Chinese experienced massive unemployment once the trans-continental line(s) was/were finished.

“On May 10, 1869, when the railways from the east and west were finally joined at Promontory Point, Utah, the Central Pacific had built 690 miles of track and the Union Pacific, 1,086 miles... This accomplishment created fortunes for the moguls of the Gilded Age, but it also exacted a monumental sacrifice in blood and human life. On average, for each two miles of track laid, three Chinese laborers were killed by accidents. Eventually more than one thousand Chinese railroad workers died, and twenty thousand pounds of bones were shipped back to China.

"Without Chinese labor and know-how, the railroad would not have been completed. Nonetheless, the Central Pacific Railroad cheated the Chinese railway workers of everything they could. They tried to write the Chinese out of history altogether. The Chinese workers were not only excluded from the ceremonies , but from the famous photograph of white American laborers celebrating as the last spike, the golden spike, was driven into the ground. Of more immediate concern, the Central Pacific immediately laid off most of the Chinese workers, refusing to give them even their promised return passage to California." (Iris Chang, The Chinese in America, 2003, pp 63-4)

Thomas Hill 1881 Driving the Final Spike (at Promontory Point, Utah). Two Chinese appear, inconspicuously, beside the tracks on the left. Leland Stanford, the founder of Stanford University and one of the builders of the Central Pacific,stands between the tracks. He refused to pay Hill for the painting. Public domain image from Wikimedia.

(click to enlarge)

How Many Chinese Died in Building the Transcontinental Railroad?

Introduction

Writers of Chinese American history often say "thousands." As shown by the above quotations, such high estimates are common. The writers blame the ruthlessness of American capitalists and, sometimes, the callousness of traditional Chinese officials toward human life. And yet it seems almost incredible that the mortality rate could have been that high without protests as well as grisly newspaper descriptions and outraged editorials. Those do not exist. Could Chinese labor contractors, American newspapermen, and officials back in China really have ignored the deaths of thousands of Chinese workers? How could Chinese railway workers themselves not have known that their jobs were death traps? Could new recruits for such jobs have still been found after several years of railway building in a part of the Sierras that was in constant communication with nearby Sacramento, with its large Chinese community that would surely have known about so many deaths? Could those recruits have been all that ignorant, desperate, or stupid?

Chinese and white workers clearing the way for the Central Pacific, 1869. From Harper's Magazine.

The answer is clear. The story about thousands dying on the CPRR is just a myth. For arguments and evidence pro and con, click here.

[Dark pink -- click to see. Light pink -- not ready yet]

Did the Chinese Railroad Builders Receive Credit for their Work?

In a word, no. There were a few instances of praise for their epic work on the Central Pacific. But otherwise white observers hardly noticed them in connection with any other railroad, even though until 1900, Chinese helped to build just about every railroad west of the Rockies. After 1900, Asian railroad labor in the U.S. tended to be Japanese and Filipino. Chinese by then, due to the various Exclusion Acts, were too few and old for the heavy work of cutting, grading, ballasting, and track laying.

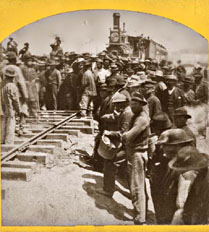

Modern commentators often point to A. J. Russell's famous photograph of the golden spike-driving ceremony at Promontory Point as proof that the Chinese contribution was devalued. The photo does indeed suggest this, showing many European-Americans at the ceremony but not a single Chinese. Interestingly, however, Russell did produce a photograph showing numerous Chinese on the same occasion. In 1881, at the orders of Leland Stanford, the artist Thomas Hill included a pair of Chinese in his equally famous painting of the Promontory Point ceremony.

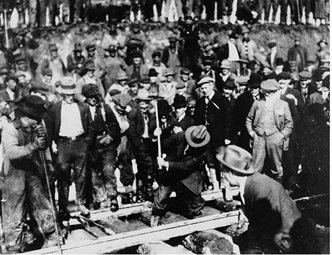

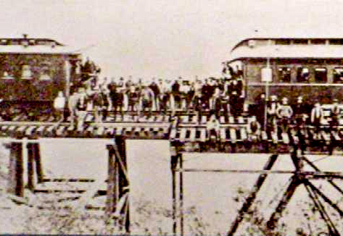

This was the last time for Chinese railroad workers to gain even that much recognition. Golden (or silver) spike ceremonies were subsequently held at the completion of many long-distance rail lines, including the next six transcontinental lines: the Southern Pacific in 1881/1883, the Northern Pacific in 1883, the Canadian Pacific in 1885,the Santa Fe in the late 1880s, the Great Northern in 1893, and the Grant Trunk Pacific in 1914. Chinese worked on all except the Great Northern, which employed Japanese instead. They had graded the right-of-way and often laid the track at the point where the final spikes were driven. Yet on each occasion they were excluded from official commemorative photos.

A. J. Russell: Chinese at the Golden Spike ceremony, 1869

A. J. Russell: The Golden Spike Ceremony at Promontory Point, Utah, 1869

Thomas Hill (1885): the Golden Spike ceremony. Note the Chinese on the left

Silver spike ceremony, Texas, Southern Pacific, 1883

Final spike ceremony, Montana, Northern Pacific, 1883

Final spike ceremony, British Columbia,Canadian Pacific, 1885

Final spike ceremony, Washington, Great Northern, 1893

Final spike ceremony, British Columbia, Grand Trunk Pacific, 1914

FINAL SPIKE CEREMONIES WITH NO CHINESE

+ Introduction [02-22-2012]

+ Did Chinese Workers Get Respect? Credit? [04-23-2012]

+ Final Spike Ceremonies with No Chinese [04-27-2012]

That Chinese railroad labor was so much devalued can probably be explained in part by the locations of the transcontinental lines. Four of the seven final spike ceremonies were in the Pacific Northwest, where anti-Chinese sentiment among white railroad workers was particularly virulent and long-lasting.

Cannery Workers 罐头渔濕业

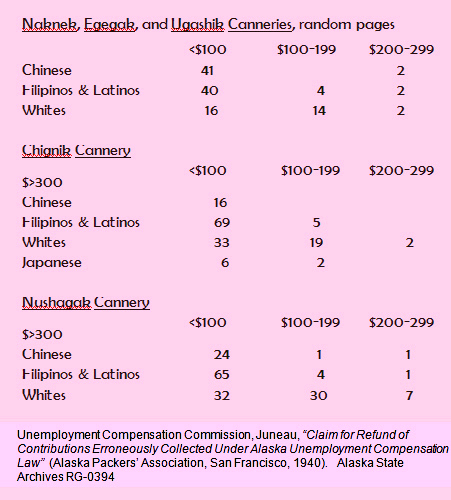

Ethnicity and Wages at Canneries 罐头- 渔濕工友工资

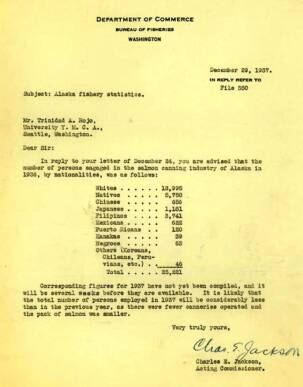

In the beginning, most of the workers in the Alaskan and British Columbia salmon canneries were either Native Americans (i.e., First Nations) or Chinese. Later, Japanese, Filipinos, and Latinos (Puerto Ricans as well as Mexicans) began to take cannery jobs in large numbers. In the 1930s, Filipinos were the most Asian numerous group.

Ethnic Groups in Alaskan Canneries, 1936

(Official US Dept. of Commerce letter)

Wages of Ethnic Groups in Alaskan Canneries, 1939

(Statistics compiled by CINARC from Alaska State Archives)

Data on wages comes from the extensive documentation assembled by the Alaska Packers Association In 1939, in connection with a dispute between the state government of Alaska and salmon packing companies in San Francisco. The issue was whether the packing companies owed unemployment compensation taxes on wages paid to out-of-state cannery workers while en route between cities in the Lower 48 (San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle) and the Alaska canneries. The packers maintained that they did not owe a penny, as the ships carrying the workers were not in Alaskan waters for most of their route. Alaska disagreed. It wanted the money.

Alaska lost the fight. However, the assembled data are most interesting. As one might expect in those racist years, most Asians were paid less than many white workers. Less expected is the fact that some Asians were paid more than many whites. Thus, the wage differential between Asians and Europeans was real enough but the packers, prejudiced as they may have been, seem not to have thought that all whites were more valuable as workers than all Chinese and Filipinos.

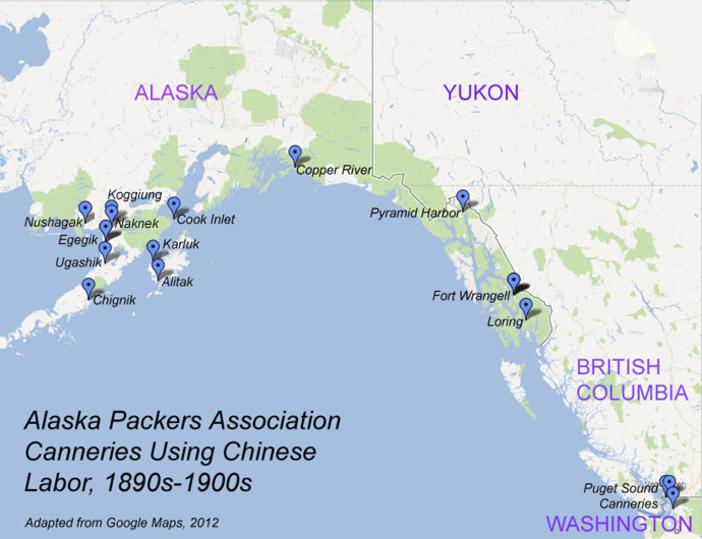

The Alaskan Canneries 亚拉斯加三文鱼罐头厂

The most profitable salmon canneries were those in Alaska and upper British Columbia. They were also the most expensive to supply and the hardest to find workers for. The jobs involved were messy, unpleasant, and boring, but not too badly paid. Perhaps the worst part of working in the northern canneries was the isolation. In such cannery centers as Astoria in Oregon, Belllingham in Washington, and Steveston in British Columbia, a semblance of community life was possible. In Alaska, each workplace was many kilometers from the next, and--because there were no roads--most could only be reached by sea. This meant that workers were trapped for the several months duration of the salmon season, with no more than 200 men for company and nothing to do except work, eat, sleep, and, depending on ethnic and personal preference, drink, quarrel, smoke (tobacco or opium), or gamble.

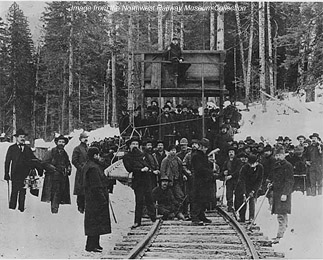

Chinese were already working in canneries in California and Oregon when the Alaskan fisheries became active in the 1880s. Thus, they moved north with the salmon fishers and packers. Between the 1880s and about 1910, they were the dominant labor force at Alaskan canneries.

The isolation and great distances involved are illustrated by the following map.

George Brown Goode in his classic Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States (1887, Part 2, Sect 4, p 48) describes the canneries of Astoria and its neighbors at their high point of prosperity:

Salmon and Chinese 华工与三文鱼罐头业

Over the years in the Pacific Northwest, salmon canneries probably employed more Chinese than any other industry. The first northwestern cannery to employ Chinese labor was George Hume's Eagle Cliff on the Washington side of the lower Columbia in 1872, and by 1880 more than 4000 Chinese were canning salmon near the mouth of the Columbia in Washington and Oregon (Note 1). The first on the Fraser River was at Brownsville opposite New Westminster in 1870-1, and the first on Puget Sound was at Mukilteo in 1877 (Note 2); canneries in both areas seem to have used Chinese workers from the beginning. The first in southeastern Alaska was the North Pacific Trading and Packing Company's Klawack or Klawork cannery, which opened in 1878; at first, Klawack may have employed only local Indians but Chinese workers soon became the norm at most other Alaskan canneries (Note 3). The salmon packing operations in the most productive of all salmon fisheries, those of central (Copper River, Chignik, etc.) and western Alaska (Nushagak and other Bristol Bay canneries), began in 1882 and 1884; all were heavily dependent on Chinese labor. By 1897, when Chinese workers were already becoming scarce in the Lower 48 due to the Exclusion Laws, salmon in Alaska were still butchered and canned mainly by Chinese. Altogether, the territory's canneries in that year employed 2,268 Chinese, 312 whites, and 39 natives (Note 4).

Note 1. HistoryLink-- http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=8036

Note 2. Richard Rathbun, A Review of the Fishing in the Contiguous Waters of Washington and British Columbia, pp 318-320. Annual Report of the U.S. Fish and Fisheries Commission, 1899.

Note 3. Pat Roppel in a Capital City Weekly article (http://www.capitalcityweekly.com/stories/071311/out_856641715.shtml) states that Chinese were employed at Klawack from the beginning. However, the authoritative Jefferson Moser (The Salmon and Salmon Fisheries of Alaska, Government Printing Office, 1899: pp 109-111) is clear that Indians supplied Klawack's full labor force until 1896

Note 4. Moser 1899: pp 49-50

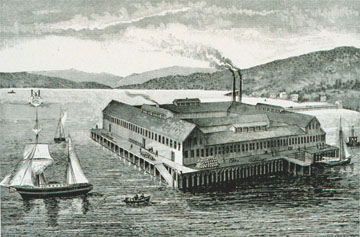

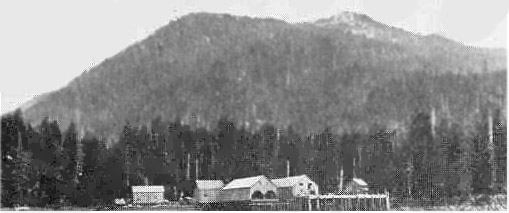

Kasilof Cannery (on Cook Inlet, Central Alaska) in 1894. The cannery was originally built in 1882 by F. P. Kendall of the American Can Co., with the assistance of his foreman, Chew Bun. Chew later became a major labor contractor in San Francisco. Photo from Pacific Fisherman Yearbook, 1921.

"On the Columbia River, Oregon, as many as three thousand Chinamen are engaged in the salmon canneries. After the salmon have been thrown into a heap on the wharf, the Chinamen cut off the heads, tails and fins and remove the viscera. Some Chinamen become so expert at this branch of the work that they can thus clean 1,700 fish per day. After the fish have been washed and cut into sections they are split into three pieces by the Chinamen, one piece being large enough to fill a can, the others smaller. These fragments are placed on tables at which the Chinamen stand ready to pack them. Other Chinamen put on the covers while yet others solder them where this operation is not done by machinery.

"The Chinese thus do the bulk of the work at the salmon canneries. The supervisors, foremen and bookkeepers are, however, white men. The fish cutters if expert receive from $40 to $45 per month. The majority receive $1 per day of eleven hours and work as required; that is, leaving and coming at any hour that may be set, time during which they are actually at work alone being counted. No other race of people could work at such rates and upon such terms as these and in the present state of things, but for Chinese labor, the canneries must needs be closed. They come in April and leave in August and very few return. They are employed directly and without the aid of any agent. [editors' emphasis]

"The Chinese as a rule work very faithfully. They are never engaged in any drunken riot and their work is uniform. On the other hand they are not devoted to their employers. If dissatisfied they are the hardest class in the world to manage. They would use a knife for two cents. If their pay should exceed a day's indebtedness they would very probably resort to foul mean work. They are inveterate gamblers and their wages as earned go from one to another to pay their gaming debts.

"A Chinaman dare not fish in the Columbia it being an understood thing that he would die for his sport, They are only tolerated because they will work for such low wages. Each cannery employs from one hundred to two hundred Chinamen."

Goode may have been wrong in his assertion that Chinese workers were hired directly, without the aid of any agent. As far as the editors know, the Columbia River canneries did most of their hiring through labor contractors, most of them Chinese themselves.

Readers will note that in 1887, in spite of what Goode says, $40-45 per month was fairly good pay by the standards of most parts of the world, including the eastern U.S. For instance, as late as 1910, 63% of full-time male workers in the Chicago stockyards were earning less than $12 per week for similar work, cutting and canning meat (J. C.Kennedy et al., Wages and Family Budgets..., 1914, p 12, Table III}.

Chinese Workers in the Columbia River Canneries

哥伦比亚河域的渔濕华工

Cannery on the Columbia near Astoria, 19th century. From Wikipedia

Why Chinese were not expelled from Astoria in 1886

俄勒岗州的埃士左利市缘何不参与排华?

In the terrible years of 1885-1886, when Chinese were being driven out of cities all over the West Coast. including Tacoma and Seattle, Astoria protected its Chinese. According to the Daily Morning Astorian (1886-02-09, p 2), this is why:

Driving Chinese out of Seattle, 1886. From West Shore magazine

The expulsion of the Chinese from our neighboring city [Tacoma, in November 1885] has been bought at fearful cost.

The question of greatest importance to us here is just how it is going to affect Astoria. We are peculiarly situated. It appears impossible to run the canneries without Chinese labor, and if that be granted it amounts to this: no Chinese, no canneries; no canneries, no business. We think the natural good sense of this community will note the trouble and turmoil of our neighbors, trouble and turmoil that similar action would here increase in proportion to the magnitude of the interests involved. On the [Puget] Sound, in California, comparatively trivial interests were at issue. Here, on the lower Columbia, the existence of the leading manufacturing industry north of San Francisco is mixed up in this wretched Chinese business, and interference affects in the most intimate manner the prosperity of every one directly or indirectly concerned ...

The expulsions of Chinese from Seattle and Tacoma, as well as their attempted expulsion from Portland, are discussed elsewhere on this website. Here it is enough to suggest that the relatively tolerant attitude of northwestern Oregonians. which led to Portland becoming a major center for American Chinese life, may have been based as much on economics as on human decency and regard for justice.

Salmon and Chinese [05-30-2012]

Chinese in the Columbia River canneries [11-10-2009]

Why Chinese were not expelled from Astoria in 1886 [05-31-2012]

The Alaska canneries [05-30-2012]

Ethnicity and wages at Alaska canneries, 1930s [05-29-2012]

Labor contractors [05-30-2012]

An exclusive (and highly successful) contractor for the PAF [06-01-2012, revised 07-20-2012]

Ah King's rules for contract laborers [06-03-2012]

This page was last updated: August 30, 2018

Contractors 包工头

Becoming a contractor for Chinese labor must have been the ambition of many Chinese immigrants. That was where the big money was. And of all labor contracting situations, that involving canneries may have been the most profitable. Demand for workers was stable but seasonal. The tasks involved required some workers with experience and many without. Those tasks were unpleasant enough that most white Americans refused to do them. Contracting for Asian laborers, first Chinese and then Japanese, Mexicans, and Filipinos, was a natural solution.

Relations between contractors and cannery owners or "packers" on the one hand and between laborers and contractors on the other, were complex. There was much exploitation and some outright oppression. On the other hand, workers often formed friendly relations with contractors, and it was almost essential for an aspiring contractor to be able to work smoothly with cannery owners, especially if he hoped to continue working with the same owners year after year.

For more on labor contractors from a business standpoint, click here.

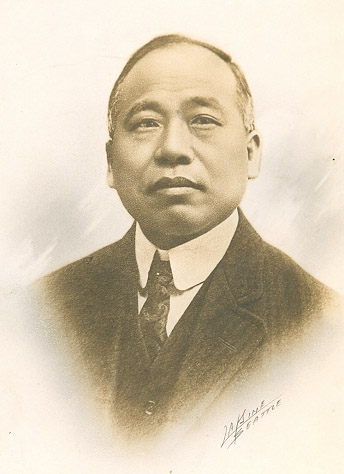

An Exclusive (and Highly Successful) Contractor for the PAF

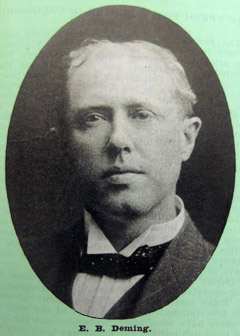

August Radtke writes that Goon Dip 阮洽, a Chinese resident of Portland, began supplying cannery labor to E. B. Deming, the most important salmon packer in Puget Sound, as early as 1900. HistoryLink says that Deming and Goon Dip did not meet until 1909, in connection with the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. Whenever they met, the two became not only business associates but also fast friends.

Deming's Bellingham (WA)-based Pacific American Fisheries at one time had thirty canneries in Washington, Alaska, and British Columbia. Its workers, at first mainly Chinese and then increasingly Japanese and Filipino, must sometimes have numbered in the thousands. If Goon Dip's contracts did indeed cover all of the company's canning operations, this alone was enough to make him a very wealthy man.

For decades, the San Francisco-based Alaska Packers Association operated more canneries (see the above map) and produced more cans of salmon than any other company in the world.

During the period 1892-1908, the APA worked with a total of 46 Chinese contractors to recruit workers for its canneries. The Business page of this website presents the first published list of those contractors. Some only lasted a year or two but others enjoyed stable long-term relationships with the APA which could last a decade or more. As the APA’s headquarter were in San Francisco, naturally their contractors were based in that city. A few were Portland-based. A couple could have been in Seattle.

It should be mentioned that the two decades discussed here saw two major innovations that affected the number of Chinese workers at each cannery. The first was the adoption at all APA canneries in or about 1904 of the so-called "Iron Chink" salmon butchering machine, which greatly reduced the demand for a highly paid group of workers. The second was the use of Japanese workers and a few Japanese labor contractors after 1905. Filipinos may or may not have joined the APA work force at this early date. If they did, they were likely listed as "other" ethnic groups.

Labor contractors for the Alaska Packers Association, 1892-1908

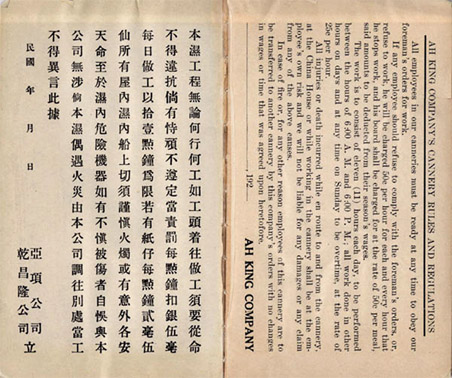

Ah King's rules for contract laborers

The legendary Ah King (Ng Hock Moy) made his name as the only Chinese-American vendor for the 1909 AYPE (Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. Although he died mysteriously in 1915, his son continued the labor contracting business under the name of the Ah King Company, also known as Ken Chung Lung & Co. 乾昌隆. The bilingual pamphlet shown here. detailing rules for workers and dated to the 1920s, cannot have been read or understood by the average worker, who was likely to be illiterate in both English and Chinese. It must have been intended as a reminder to supervisors and as a legal basis for disciplinary action. The document emphasizes that laborers were expected to work hard and that they would get little or no protection in the event of illness, accident, or labor disputes. For more on Ah King's businesses, click here.

Rules for cannery workers, Ah King Co, 1920s. Editors' photo, from Wing Luke Museum, Seattle.

Whereas a number of contracts (often called simply "agreements") between cannery owners and labor contractors have survived (for instance, in the archive of the Gulf of Georgia Cannery in Steveston, B.C.), contracts in the other direction, between contractors and cannery laborers, are rare. The editors have not seen actual examples. The Delta Museum and Archives in Delta, B.C., has a number of contracts between cannery owners and individual fishermen that feature some of the same language as the Ah King Company's rules and regulations. Part of the problem is that the records of Chinese labor contractors are less likely to have survived than the records of cannery companies. However, we are hopeful that contracts with individual cannery workers will eventually turn up in one of the cities where most Chinese labor contractors were based -- that is, San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, Victoria, or Vancouver

Did Goon Dip's employees regard him as fondly as Deming did? It seems unlikely. Yet Seattle and Portland, where Goon hired most of workers, were small places in those days, and his family were there instead of in China. He might have found it difficult to treat his workers as badly as some of the San Francisco contractors. who routinely used company stores and other strategems to bleed their workers while still at the canneries, and then refused to pay them afterward.

For more on Goon Dip and Deming, click here.

E. B. Deming, ca. 1910

(UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED ALL DATA ON THIS PAGE COMES FROM THE EDITORS' OWN RESEARCH ON PRIMARY SOURCES & ARTIFACTS)

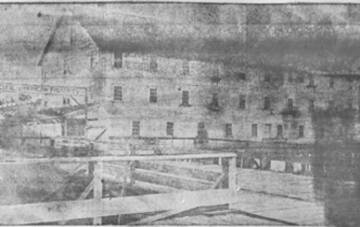

The Bright Side of Cannery Labor (Bellingham)

No one can claim that the cannery contract system was always beneficial, or even tolerable, to workers. The dark side of the subject, to be discussed presently, included poor pay, vile living conditions, extreme isolation, and being forced to purchase everyday necessities at outrageous prices from contractor-owned stores.

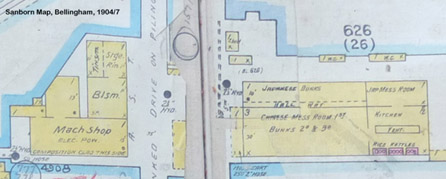

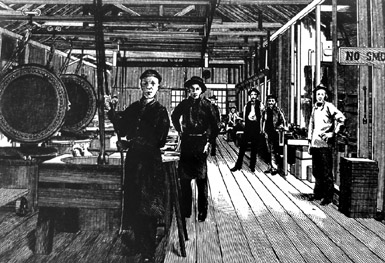

"The South Bellingham [Washington] facility for [E. B. Deming's] Pacific American Fisheries was the largest and employed hundreds of male Chinese workers [all hired by the contractor, Goon Dip] over the summer months. . .

"For some workers, this summer employment at the cannery provided their only employment because of their inability to speak English and obtain work elsewhere. They would wait out the rest of the year, often obtaining an advance before the season started in order to ensure work the following season. As the summer progressed, the regular crew was supplemented by foreign-and American-born Chinese students, some of whom worked for no pay at all. Goon Dip stated on many occasions that students needed the work more than the other workers because of the need to finance their education. For those lucky enough to be selected, cannery work was virtually an ideal situation. South Bellingham had a movie theater, a library, and parks in which workers could spend their long summer days when the work slackened. In exchange, Goon Dip would often finance and entire college education. It was common for him to provide a promising student with tuition for his education as a loan and many students would flock to his office because of his generosity."

(Silas G. Jue and Willard G. Jue, Goon Dip: Entrepreneur, Diplomat, and Community Leader," Annals of the Chinese Historical Society of the Pacific Northwest, 1984, pp 46-50)

There was a brighter side, however. Present-day interviews with former Chinese American and Chinese Canadian cannery workers tend to elicit surprisingly positive feelings about jobs and bosses. Some evaluations are so positive as to awaken doubts about the objectivity of the commentator. For instance,

Pacific American Fisheries' (PAF's) China House, Bellingham, one of the few existing images. Galen Biery's PAF Scrapbook Box 9, Center for Pacific Northwest Studies, U. of Western Washington. Originally from Bellingham Herald (?), 1944 (?)

Location of PAF's China House. Sanborn Maps, Bellingham, 1907.

The kitchen is at lower right. Click to enlarge.

Kitchen, China House, Bellingham. 1910s? Galen Biery's PAF Scrapbook Box 13, Center for Pacific Northwest Studies, U. of Western Washington.

". . . the China House was a community unto itself. It contained not only bunks and living quarters for 200 or more persons but a kitchen, eating room, storeroom, and a Chinese store. It was the center of Chinese "night life" in this area and it had its Oriental games and music, including games of chance, its celebrations, and even strife."

(For source reference, see caption to image at the beginning of this article. For Bellingham's (mythical) Chinese dead line, see Google results for "Chinese Deadline Bellingham."

The existence of a special China House for Chinese cannery workers in South Bellingham shows that they were indeed segregated. According to local legend, Chinese were forbidden to pass a so-called Dead Line that separated the cannery area from the city's business and residential districts. And yet descriptions of life there are not all that negative. For instance, back in the still- prejudiced 1940s, a local newspaper could write positively that

A positive view of cannery work in the post-WWII era also appears elsewhere on this website, in comments and photo-graphs by Fred Wong of Portland.

Mining

Chinese Miners at Cumberland 加拿大卑斯省金巴仑煤矿华工烟罐

In an email to the editors, Reg speculates that Roy's cans may have come from the large Chinese settlement at Vancouver Island’s long-lived and productive Cumberland (originally named Union) coal mines:

I was just thinking of Cumberland on Vancouver Island. There was a large active coal mine there from the late 1800s until mid 1900s. There were a lot of Chinese miners there. I have a pick head that came from there with a number on it and Chinese characters. They gave the Chinese miners numbers because the foreman was not expected to learn Chinese names. They would just yell number 19, when they wanted a specific miner. (I wonder if the white miners had numbers? Or did they say, "Hey Joe, you and number 19 over there go to drift 14"?)

The supervisors at the mines may have winked at their workers using opium. In the 1920s and 30s it was still common enough among westerners to feel that opium was not such a serious problem, especially when the users were Chinese.

Note: Reg is the webmaster of the North American Pioneer Chinese Virtual Museum, based in Williams Lake, B.C.

http://www.chinesecol.com/treasure6.html.

The following article is the first of several that will be added ion the next few months --14/2/2013

The Chinese "Alaskeros" [a useful Filipino-Mexican term for seasonal workers in Alaskan canneries] were surprisingly old. Most were relatively prosperous too. Assuming that funeral costs came out of the back pay owed to the deceased by the cannery contractor, ten of the sixteen must have been better off than the average cannery worker of that period. In 1906, “Oriental” laborers in the Fraser River canneries received $30-40 per month (Pacific Fisherman 1906 Yearbook, p 32). As late as 1940, ordinary Alaska cannery hands of all ethnic groups received less than $100 for a 3-month season (see the preceding article). The ten workers whose bodies went back to Portland or Seattle (at an average cost of $123.50) must therefore have been in better-paid positions. The five workers whose bodies were buried in Ketchikan (at an average cost of $61.90) may reflect a more usual pay scale.

Why was the pay scale of some Chinese so high? Supply and demand may be the explanation. In the 1900s-1910s, experienced Chinese cannery hands were already becoming scarce, due to American restrictions on immigration and a sharp recent increase in the Canadian head tax, while substitutes from other ethnic groups with equal experience were rare. The result was that veteran cannery workers often held more responsible and better-paid positions.

The funeral costs seem very high anyway. The undertakers evidently were charging as much as the traffic would bear. How did they know how much that was? There may well have been collusion between the funeral home and the Chinese paymasters of the cannery contractors. Together they may have taken the opportunity to help themselves to most or all of the dead workers' back pay.

For causes of death of Chinese cannery workers at Ketchikan and what happened to their bodies, click here.

Note: The canneries in question were those of Alaska Pacific Fisheries as well as Chomly, Hidden Inlet, Kasaan, Ketchikan, Lindenburger, Loring, Roe Point, Scowl Arm. Sunny Point, and Yes Bay. The only named contractors were Gee Wah Bing Kee and Kwong Man Yuen, both of them companies in Portland.

Elderly Chinese Cannery Hands and Costly Funerals at Ketchikan, 1910s

The editors recently were introduced to the city archival records of Ketchikan, Alaska, through the kindness of Richard Van Cleave, Senior Curator at the Tongass Historical Museum. The archives are a key source for the history of Chinese in the far south of the Alaskan panhandle, just north of the border with British Columbia.

Ketchikan had few year-round Chinese residents, and those it had—except for the victims of a spectacular double murder in a gambling den—led inconspicuous, un-newsworthy lives as laundrymen and restaurant owners. However, the city did have a number of nearby salmon canneries with many seasonal Chinese workers. These rarely came into town while alive but, for legal reasons, had to pass through there if they died. Fortunately for historians, records of deaths do survive. Most important are those kept by Ketchikan’s leading funeral home, which handled the bodies of locally deceased individuals from many ethnic groups. These records cover the years 1911-1921 and give names, dates, causes of death, mortuary services provided, cost, and—not unimportantly—who paid those costs.

A total of 20 deceased Chinese passed through the funeral home between 1911. The occupations of two was not specified, while one was a cook and one a restaurant owner. The other sixteen were cannery workers. All of the former and five of the latter were buried in Ketchikan, perhaps permanently. The other eleven cannery workers were embalmed, placed in coffins, and shipped back to either Seattle or Portland, depending in part at least on where their winter homes or labor contractors were located.

Average age at death

52.8

52.8

48.0

48.0

Disposition:

Buried in Ketchikan

5

5

3

3

Funeral, etc, cost

$61.90

$61.90 $110.80

$110.80

Sent to Portland or Seattle

10

10

0

0

Funeral, etc, cost

$123.50

$123.50

-

-

Not recorded

1 1

1 1

Funeral, etc, cost

$75

$75

?

?

High tide at Ketchikan, ca. 1900. Credit: Library of Congress

The Only First-Hand Chinese Account of Cannery Work Before WWII?

笔记三文鱼罐头厂第一华人?

A noted intellectual in China, Li Gongbu 李公僕, became a student at Portland's Reed College in 1927. He spent the summer of 1928 working at the Union Bay Cannery in southern Alaska, partly because he needed the money and partly to experience an important side of Chinese life in the Pacific Northwest. Requested by a friend who was the editor of a Shanghai-based Chinese-language magazine, Life, Li contributed several short articles including some on his cannery job. He may have been the only one among the thousands of Chinese who worked at salmon canneries in the 1870s-1930s to have recorded his experiences in writing. He was deeply interested in problems of prejudice and workers' ethnicity. On the other hand, he does not seem to have felt that he himself was treated badly during the three months he worked at Union Bay.

"Workers’ lives here are mostly organized according to their skin color – they work, eat, and sleep in separate masses according to their ethnic affiliations. White people are a group; Japanese, Chinese, and Koreans another group; Filipinos belong to yet another. Blacks and Indians [Native Americans] sleep and eat as a group since they mostly involved in fishing. The labor operation of this cannery up to last year was under a Chinese contractor who hired mostly Chinese. I heard that because of poor management, the bedrooms were not cleaned and work was not done well, so the owners changed to using Japanese contractors . . . 80% of the workers here are Chinese, Japanese, and Filipinos because they accept hard-board beds, plain white rice, and relatively low pay . . . Once I visited the white workers’ mess. The place is definitely nicer and cleaner than ours. This is partly because they get higher pay, and partly because they are accustomed to cleanliness.

"People have different ways of entertaining themselves. White workers like playing chess and cards, fishing, talking, sleeping, and swimming. Japanese are fond of gambling – sometimes that is where they spend their salary. Filipinos love playing music. They often hold dancing parties on the beach together with the blacks and the red girls. Sometimes the white men join them too. Occasionally Indian girls sing in their language. Though incomprehensible, this is often lovely to hear. . ." (August 15, 1928; translation by Chuimei Ho)

Union Bay Cannery near Ketchikan, Alaska, Pacific Fisherman Year Book, 1917

Li, highly educated, sophisticated, and a skilled writer, was not at all a typical cannery laborer. On the other hand, his observations are those of an unprivileged insider. As such, they may be unique in the early history of Chinese working in American canneries. Click here for fuller excerpts from Li's Alaska articles.

Li Gongbu 李公僕