For the first few years of Chinese immigration, there was no fixed system for repatriating the dead. Regional associations or huiguan played a role. So did families and associates, perhaps often fellow members of secret societies. With a decade or two, however, the process had become systematized. Responsibility for exhuming and sending back the dead lay in the hands of the appropriate district association or huiguan, which may have maintained the necessary records but usually delegated the task of handling the bodies to subordinate charitable organizations or shantang. Teams from the shantang would go out every ten years or so to make the rounds of known cemeteries and other burial places. Experienced individuals on those teams would undertake negotiations with the local white authorities, pay the necessary fees, and proceed to empty the graves of all deceased individuals from the district in question.

Still later, by 1900 if not before, the national and local Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Associations took over from the district huiguan. Most of the exhumation and body shipment records we possess date from the CCBA period. Bodies have not been shipped to China since 1937, when the Japan-China war made such shipments impossible. Yet in some North American cities, the CCBA still plays a related role, purchasing blocks of land at local cemeteries and selling grave plots to Chinese residents.

Death: Reburial Articles

D. Exhumation and Shipment to China 先友回唐

Until the late 1930s, most Chinese who died and were buried in the Pacific Northwest and West (as well as many of those who died elsewhere in North America) were dug up again after a number of years and sent back to China.

(0) Why? 何必如此辛苦经营?

(1) Reburial customs among the Southern Chinese 华南流行二次葬 12/22/2011

(2) MarkTwain on the return of Chinese bodies to China 马克吐温对执运的观察 12/26/2011

(3) How exhuming and repatriating bones was organized in Canada 加拿大执运先友善堂 05/10/2012

(4) Registration for exhumation and body return 域多利是加拿大执运先友的总站 12/27/2011

(5) Women in the burial registers - Victoria cases 域多利女先友的执运纪录 12/27/2011

(6) Digging up the dead: Who did it? How? 執骨工人是誰? 01/03/2012, revised 03/21/2012

(7) The perils of exhumation: a ghost story 2/25/2013

(8) How to tell whose bones they were: an answer from Alaska 05/24/2012

(9) Rules for digging up the dead - San Francisco 三藩市怎样管理执骨, 洗骨 03/10/2012

(10) Packing the bones in Victoria and Portland -- why metal boxes? 域多利,钵仑怎样装载骨殖? 03/10/2012

(11) How exhuming and repatriating bones was organized in San Francisco before 1900 三藩市怎样管理执骨, 洗骨, 运骨. 1930之前 01/03/2012

(12) How exhuming and repatriating bones was organized in San Francisco and Victoria after 1900 三藩市, 域多利怎样管理执骨, 洗骨, 运骨. 1930之后 01/03/2012

(13) Seattle: other Chinatowns played a role in repatriating the dead 西雅图也参与执运工程 01/04/2012

(14) Storing the dead before shipment in Victoria; Larry Wong's remarkable photo 绝无仅有的照片 -

王容伦拍的域多利贮骨所 revised 01/13/2012

(15) Shipping the dead to China

E. After the Bodies Reached China 从香港到故里

Virtually all Chinese remains that arrived back in China were processed through the Tung Wah Hospital, Hong Kong's leading charitable institution. Ideally, remains of each individual would then be passed on to family members for placing in suitable containers, usually jars, and interring in family cemeteries where offerings to the dead would be made regularly, especially on the Qing-Ming Festival in th spring and the Hungry Ghost Festival in the fall. Inevitably, however, some remains would not be claimed. Those would accumulate at the level either of Tung Wah in Hong Kong or of charitable organizations in the relevant home district. Those organizations would bury such remains in charity cemeteries, sometimes in mass graves with a single monument and sometimes in separate graves with individual markers..

(1) The central role of Hong Kong's Tung Wah Hospital 中介站-香港东华医院 12/23/2011

(3) Unclaimed bodies: charity cemeteries in China 义冢安葬 無主孤魂 12/28/2011

(4) Claimed bodies: burial in the family cemetery 入土为安 – 故乡是先友的终点站01/07/2012

(5) A lone voice spoke out: bone repatriation was a bad idea 孤掌难鸣 - 执运先友害处多 04/23/2012

Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee (CINARC)

The Key Role of Hong Kong's Tung Wah Hospital 中介站 - 香港东华医院

Virtually all Chinese remains that were returned to China went through the Tung Wah Hospital 東華醫院, opened in 1872 and Hong Kong's leading charitable institution ever since. Overseas Chinese organizations, often home district associations (huiguan) or their charity arms (shantang 善堂), having paid shipping costs in advance, would notify Tung Wah that a shipment was on its way, with as much information as possible about the names and home villages of the deceased, as well as the name and arrival date of the ship. Tung Wah, in turn, would notify organizations and clans in the relevant places and would also place advertisements in local newspapers . When the ship arrived, Tung Wah would arrange for one of several undertaker firms to bring the remains back to the hospital grounds. After 1899, the remains were stored temporarily in the so-called Coffin Home. District organizations and clans would arrange either to pick the remains up themselves or pay one of the undertaker firms to deliver them in China.

C. Exhumation and Shipment to China 执运先友回唐.手续繁复

Reburial Customs of the Southern Chinese 华南流行二次葬

Although the custom is dying out, secondary burials are still performed, even in modern Hong Kong and Macao. A shortage of cemetery space is not the explanation: secondary burial traditions in southern China are much too ancient and widespread for that. They may well go back to the days before the northern Chinese conquest in the late first millennium BC, when the ancestors of most Southerners had non-Chinese cultures and spoke non-Sinitic languages

The editors of this website, including Larry Wong, posted some information about Chinese reburial customs on the Ask Larry page of the Chinese Canadian Historical Society of BC website. For most peoples, including the great majority of northern Chinese, the task would have been a horrifying one filled with spiritual danger. Southern Chinese in North America, however, seem to have handled it without problems, quite possibly because some of them while still in China had learned the procedures and rituals involved.

Perhaps because of taboos surrounding the subject, surprisingly little has been written about Chinese secondary burials. Timothy Y. Tsu of the National University of Singapore has published a good article on secondary burial in a Chinese village in southern Taiwan. A now-classic general source is James L. Watson and Evelyn Rawski, Death Ritual in Late Imperial and Modern China, 1988, especially the chapter by Rubie Watson. More data, mostly in the form of brief comments, can be found by.searching for "secondary burials Chinese" in Google Books.

The Cantonese custom of secondary burial, the idea of exhuming the dead, cleaning the bones, and then burying them again, helps to explain why so many Chinese in North America were not only willing to exhume their dead but also to clean the bones and put them in containers for shipment back to China.

The custom is ancient. It is shared by certain Malayo-Polynesian peoples (for instance, by the Toraja of Sulawesi, most Dayaks of Borneo, and most ethnic groups on Madagascar) and by other southern Chinese (in southern Fujian, and Taiwan as well as Guangdong).

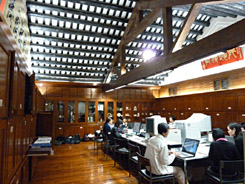

Former headquarters, now the museum and archives, of the Tung Wah Hospital in Hong Kong

Volunteers scanning documents in the Tung Wah Hospital archives. Many such documents relate to the reception and onward shipment of Chinese remains from foreign countries 东华三院档案馆

The hospital still stores many sets of human remains that were returned from overseas in earlier times. In 1960 its Coffin Home housed no fewer than 670 coffins, 8060 exhumed bodies, and ashes from116 cremations. Most of the exhumed bodies came from Southeast Asia and North America. For political reasons they were stuck in Hong Kong; it was not possible at that time to send them across the border to China.

Tung Wah Coffin Home entrance, from Wikipedia

东华义庄

Reburial: Exhuming the Dead and Returning Them to China 塵土歸路: 先友回唐 - 墓地 葬仪 过程

版权 Copyright is free for non-profit use: : click here for more information

金山西北角 - 华裔研究中心

Note: an excellent article on the Tung Wah Coffin Home appears under that heading in Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tung_Wah_Coffin_Home#Ossarium. A major recent book on the history of Tung Wah is that of Elizabeth Sinn, Power and Charity: A Chinese Merchant Elite in Colonial Hong Kong (Hong Kong University Press, 2003)

Unclaimed Bodies: Charity Cemeteries in Guangdong Province 义冢安葬無主孤魂

Not every set of remains was received by the family of the deceased. Some bodies that arrived in China via Hong Kong might have had so little information that it wasn't possible to connect with their relatives. Others belonged to families that for personal or economic reasons declined to bury them. Hence, a number of charitable organizations in Guangdong took it upon themselves to acquire land to bury those unclaimed bodies.

In 1887 the Guangzhou-based charity, Ai-yu Tang 爱育堂, which was an active partner of Tung Wah Hospital in Hong Kong in returning bodies to their hometowns, buried 924 set of bones that included 467 women in 1887. This burial site is still intact but is part of the yard of the Guangzhou Chest Clinic 广州胸科医院. Although the communal tomb tablet indicates the bodies were shipped from San Francisco, it is likely that San Francisco was just a collecting point for bodies dug up in many parts of America.

In 1893 the Xinhui-based charity, Renyu Tang 仁育堂, buried 387 bodies in individual graves at the Huangkang Cemetery, each furnished with an epitaph. It took the Renyu Tang five years to complete the project. These unclaimed bodies were part of a larger shipment of "Gold Mountain" bodies that reached Xinhui 新会 in 1888. Interestingly, the unclaimed deceased were not exclusively Xinhui natives. Some were neighboring county residents and some from more distant areas.

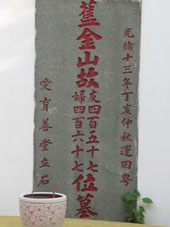

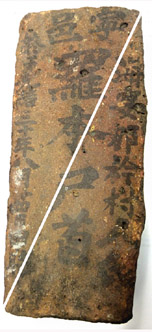

One of the markers set up by the Renyu Tang in Xinhui's Huangkang Cemetery reads:

"金山各阜先友骸骨运回本邑自光绪十

四年至十八年二月除领回安葬外尚存

三百八十七具于本年二月二十三日安葬与

此地

光绪十九年岁次癸巳仲春仁育堂谨志"

The Huangkang 黄坑Cemetery, Xinhui. A marker at the back reads, "Charity Cemetery". Only two front rows of individual burials are showing; the rest are covered by weeds.

The Ai-yu Tang's communal tomb for unclaimed bodies at the Guangzhou Chest Clinic

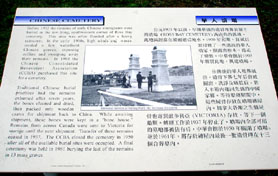

Registration for Body Return: B.C.'s Victoria as a Collection Station

域多利是加拿大执运先友的总站

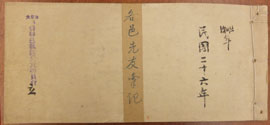

The bones of Canada's deceased Chinese in various cemeteries were retrieved, washed, labeled, and packed in tin boxes. These were in 1937 handled by the newly established Canada Oversea Chinese Amalgamated Exhumation Board 加拿大 华侨联邑 执运先友 委员会, which was largely administered by the Victoria's Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) in Victoria for delivery to Tung Wah Hospital in Hong Kong.

Victoria's CCBA helped organized bone-repatriation shipments once every seven yeaers from the 1885 onward The consignment prepared in 1937 was the last and least successful one. Because of the Sino-Japanese war broke out in China that interrupted many facets of routine, CCBA had kept the bone boxes in Victoria and reburied them in 1961 at Harling Point in Victoria. The documents of the deceased list survives in the Special Collections of the University of Victoria Library, thanks to David T.H. Lee 李东海 who assembled the documents when he was on the staff of the CCBA in the 50s and 60s, and to David Chuenyan Lai 黎全恩 who facilitated the donation to the library archive.

Only 13 women were among the 661 sets of recorded individuals in the Victoria's CCBA list. Twelve of them were married women, almost nameless; they bore their husband's, father's, or son's names. Only one was listed with her full name: she was a mature single lady who was a native of Zengcheng.

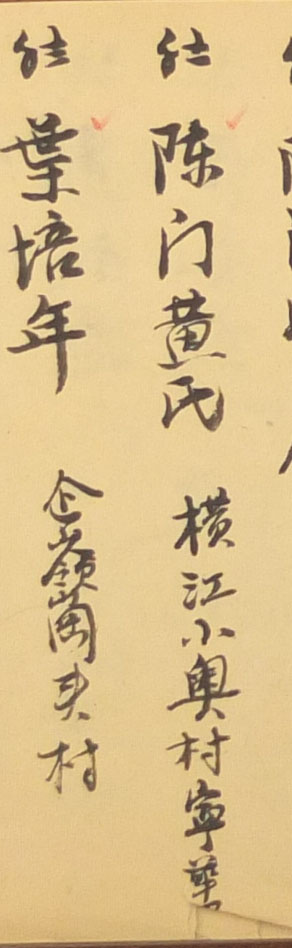

Were the bones of the married ladies sent to the hometown of their husband's family? Very likely. One lady, Mrs. Rong, was the mother of another deceased. Both sets were slated to return to the son's hometown, Mazhou village in Xinhui county (Fig.1)

The surviving documents show that each deceased individual was registered twice, first by the location where the bones were dug up, and then by the Chinese county where the deceased came from. Hence the deceased's name(s), hometown, death date, and burial place, and even the burial reporting agency were included. Most deceased had passed away a number of years previously and came from all over Canada. Apparently 728 sets of bones were dug up for shipment, but 67 sets were reburied on the spot, perhaps because they were not sufficiently decomposed for the bones to be cleaned and packed for the journey.

Taishan 台山 - 324 sets (6 women)

Kaiping 开平 - 124 sets (1 woman)

Xinhui 新会 - 118 sets (3 women)

Enping 恩平 - 26 sets

Heshan 鹤山 - 2 sets

Zengcheng 增城 - 21 sets (3 women)

Dongguan 东莞 - 2 sets

Yangjiang 阳江 - 3 sets

Registration for Body Return: Victoria Women in the Burial Records 域多利女先友的执运纪录

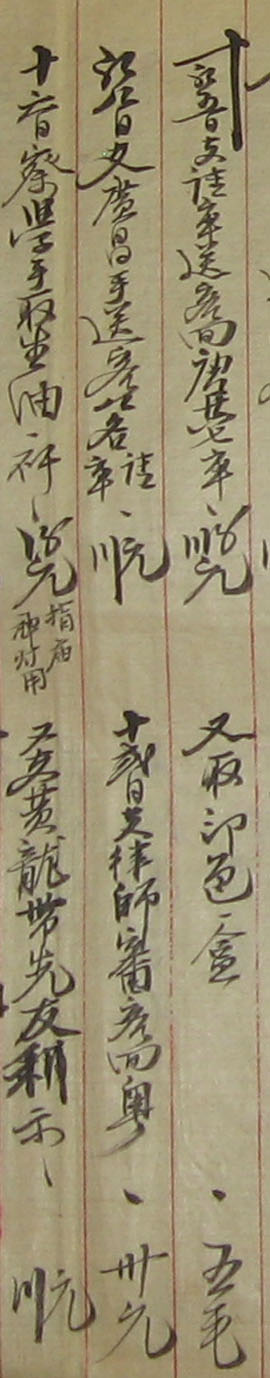

Fig. 1. Reading vertically from R to L, Mrs. Rong was listed as "Mother of Rong Delie, at Mazhou". The sixth vertical line lists her son, "Rong Delie, Mazhou".

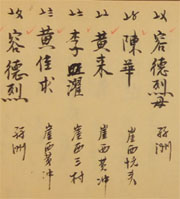

Fig. 2. Three individuals listed vertically from R to L. Mrs. Huang of the Wu family is in the middle. She was listed as 224 in the Taishan shipment, but her child, who was entered under her name, was not given a number.

Fig 4. The vertical line on the right reads "Ms. Huang married to the Chen family, Hengjiang, Xiao O Village, Ningyi [tang]."

Two of the women probably died in childbirth. They were buried together with their babies, who were nameless according to Chinese custom, and thus not counted in the burial list. One lady, Mrs. Huang from the Wu family was to be sent back to Dongkou Village in Taishan county, with her child (Fig. 2). Another deceased mother was Mrs. Huang from the Chen family who too was married to a native of Taishan county; he was from Hengjiang Village 横江 and a member of the Ningshan Tang 宁善堂 (Fig. 3). This particular record may have become confused, however. Mrs. Huang of the Chen family appeared again in the Taishan county list, but this time with her married and maiden last name switched, thus becoming a Mrs. Chen from the family of Huang (Fig. 4) -- from a traditional Chinese point of view, a very serious error. Reference: University of Victoria Library, Special Collections. Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association AR030.1.9 - 1.11.

Fig. 3. The writing indicates that Mrs. Huang of the Chen family was buried in Victoria with her child. The red ink was added to the list to show that the bones were dug up, and that she was affiliated with the Ningyi Tang.

After a suitable time had passed--at least five years and often more than ten, it was customary for most or all bodies in a given cemetery to be dug up, the bones cleaned and placed in boxes, and then sent to either San Francisco or Victoria for onward shipment to China. This sequence of events was of major concern to most Chinese North Americans. From the beginning of immigration in the early 1850s, Chinese sojourners made arrangements for their bodies to be repatriated to China in case they died.

Click here for earlier stages of handling the deaths of North American Chinese.

A. Causes of Chinese Deaths 早期華裔死因

(1) Violent Deaths in British Columbia, [Updated 01/04/2010]

(2) Chinese Suicide in Washington State, 01/04/2010

B. Chinese Funerals in North America

(1) Funerals in San Francisco and Portland, ca. 1900 12/29/2011

C. North American Chinese Cemeteries 北美洲華人坟场

(1) Lone Mountain in San Francisco 12/29/2011

(2) an unidentified early cemetery in Portland. 俄勒岗州钵仑华人墓地 10/13/2009

(3) Spokane's Fairmount. 華州士卜顷坟场纪录 12/13/2010

(5) Mountain View in Walla Walla. 落叶不归根 : 華州抓李抓嚹早期华人墓地

(6) Seattle's Goon Dip decides that his body will not be returned to China 12/27/2011

(7) Ethnic subdivisions at Harling Point: birthplace determined burial place 05/14/2010

This is one of two pages focusing on how and why early North American Chinese died, the ways in which their countrymen handled those deaths, the rituals they followed, how the dead were buried, and why and whether they were dug up again and sent back to China.

The Death: Dying & Burial page treats the earlier stages of dealing with the dead. This page, Death: Reburial, discusses what happened after the funeral and initial burial took place.

D. After the Bodies Reached China 先友到达香港之后

Photo: secondary burial jars from a cemetery at Yangjiangyi, Xinhui, Guangdong,

2011. These particular jars were used for burials of local residents, not bodies returned from overseas. Seemingly identical jars are on exhibit as products of local kilns in the Ceramic Museum at Shiwan (Shekwan), Foshan, Guangdong.

The Jinniushan 金牛山 Cemetery, Xinhui. Like the Huangkang Cemetery, a burial ground for unclaimed bodies returned from overseas. The image on the right shows how inscribed tile markers for each burial were set in concrete. The image on the left shows burial jars that have been uncovered by farm workers digging at the edge of the cemetery.

The Huangkang and Jinniushan cemeteries were kindly shown to the editors by Lin Wenbin 林文斌, a deputy director at the Xinhui Museum 新会博物馆. The communal tomb at the Guangzhou City Chest Hospital is publicly accessible; the hospital is a well known institution in Guangzhou.

Interested readers should consult Marlon K. Hom's touching and well-informed study of the Huangkang cemetery "Fallen Leaves' Homecoming: Notes on the 1893 Gold Mountain Charity Cemetery in Xinhui" (San Francisco, Chinese Historical Society of America, 2002). The cemetery has been moved to a new location further uphill since Hom's visit.

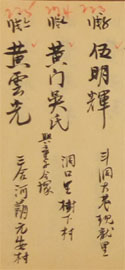

Mark Twain on the Return of Chinese Bodies to China

美国文坛巨子马克吐温对执运的观察

In 1864, while he was working as a reporter for a San Francisco newspaper, the Daily Morning Call, Twain took an interest in the city's Chinese community. He wrote at least one article on the Ning Yung Association's 宁阳会馆 temple and made the following observations, which he later incorporated in his autobiographical Roughing It (1880):

"On the Pacific coast the Chinamen all belong to one or another of several great companies or organizations, and these companies keep track of their members, register their names, and ship their bodies home when they die. The See Yup Company is held to be the largest of these. The Ning Yeong Company is next, and numbers eighteen thousand members on the coast. Its headquarters are at San Francisco, where it has a costly temple, several great officers . . ., and a numerous priesthood. In it I was shown a register of its members, with the dead and the date of their shipment to China duly marked. Every ship that sails from San Francisco carries away a heavy freight of Chinese corpses--or did, at least, until the [California State] legislature, with an ingenious refinement of Christian cruelty, forbade the shipments, as a neat underhanded way of deterring Chinese immigration. The bill was offered, whether it passed or not. It is my impression that it passed."

Twain confirms that in the 1860s the repatriation of bodies was in the hands of the regional associations or huiguan, of which the Ning Yung Association was one. The bill forbidding the shipment of Chinese bodies, which he sarcastically but perhaps justifiably calls "an ingenious refinement of Christian cruelty," seems never to have passed and become law.

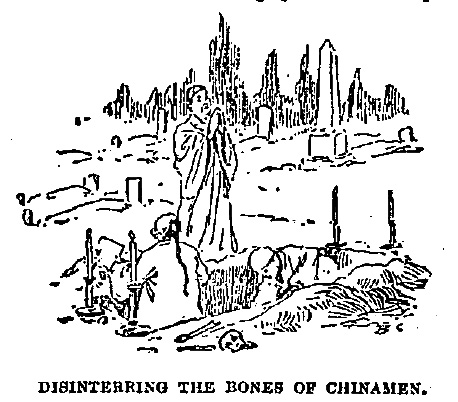

Digging up the Dead: Who Did It? How? 執骨工人是誰?

Chinese cemetery during exhumation. Chico, California (S. F. Call 1893-11-14)

Xinhui, China

Guangzhou, China

Hong Kong

Him Mark Lai 麦礼谦 (Becoming Chinese American 2004: pp 99, 114) stated that the three Sam Yup shantang in San Francisco, the Chong How Tong for Panyu county, fand the Hung On Tong for Shunde county, each owned its own charity cemetery in China, meant to provide burial places for individuals without relatives.:

Lai does not cite a source for this statement, which probably means that his information came from the records of the Sam Yup Association, to which he had access while co-authoring the official history of the Association in the 1970s.

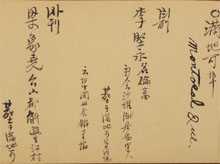

Involvement with the digging up of cemeteries was not a monopoly of an organization in a single big city in each country. In Seattle, for instance, the Chong Wa Benevolent Association 西雅图中华会馆 (CWBA, the local version of the CCBA or Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association) gave money to exhumation specialists. With other seaports like Portland, it could also have handled shipments of bones back to China. The two documents shown here, from unpublished records of the CWBA, show that it paid lai-shee, or lucky money, to a person who brought the bodies or bones back to Seattle. In the middle of the 10th month of 1892, Huang Long 黄龙 did that task and received $3 in compensation. This seems like a very small amount. Perhaps most of Huang Long's pay came from another organization, possibly in San Francisco.

The CWBA received substantial money from this business. In 1905 a sum of $102.50 was deposited with the Seattle Chong Wa by an office that handled digging and transporting the deceased. Assuming that this was real income and not a deposit of some kind, it represented the CWBA's largest item of revenue for the entire year.

The lower half of the left most vertical line reads: "Also paid lai-she to Huang Long for guiding the deceased, $3.

CWBA record, 1892.

The second vertical line from left reads, " 31st year (1905) Gee Hee brought and deposited $102.50 from the Digging Deceased office." This Gee Hee is likely to be the civic leader Chin Gee Hee. The account was managed and reported by the Wa Chong Company, which was closely connected with Chin Gee Hee.

CWBA record, 1905

Seattle: Other Chinatowns Played a Role in Repatriating the Dead

西雅图也参与执运工程

One of the few descriptions we have of such an exhumation specialist appeared in the Spokane (WA) Spokesman-Review (1896-08-15), which noted a visit by “Fang Chung, chief scraper and gatherer of the bones of dead Chinamen for the Six Companies.” He had been hired by the Six Companies (San Francisco’s CCBA) to collect a total of 500 bodies on his tour from San Francisco north to Washington State, including Spokane, then onward to Idaho, and finally back to California. According to the Spokesman-Review, Fang Chung would go on to accompany the consignment of bones to China, “where the relatives of the deceased awaited their arrival.” [quoted and paraphrased from the Spokesman-Review by Judy Nelson, “The Final Journey Home: Chinese Burial Practices in Spokane.” Pacific Northwest Forum, Vol 6, No. 1:70-76. 1993]

Whether exhumation involved special rituals, perhaps performed by a member of the exhumation team, is unclear. Rituals of some sort would seem to have been necessary when engaged in actions as fraught with supernatural danger. On the other hand, the process of preparing their bodies to be sent back home must have been seen as very welcome by the spirits of the deceased. It is possible that the danger did not seem too serious.

How would a bone packer know that he had got everything from the body? In the 19th century the Chong How Tong (Panyu) in San Francisco 番禺昌后 堂 issued guidelines to help inexperienced diggers, cleaners, and packers. Perhaps other associations had similar guidelines too. It is interesting that the pigtail itself was culturally important even after death. Here is a detailed summary:

The metal-and-wooden box system was in use as early as the1870s. In 1893 The Sam Yup Benevolent Association in San Francisco recalled their earlier bone-retrieving project in 1874 "... a not-fully decayed body was stored in a tin box as the inner container and then in a wooden box as an outer container ...."

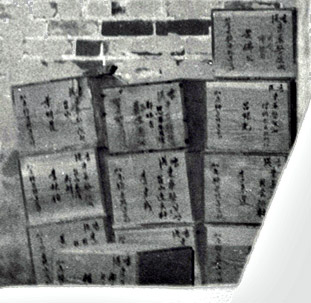

The photograph above on the right shows many wooden boxes, each inscribed with names of the deceased, their hometowns, and dates of death. The boxes were ready for shipment in the former bone vault at Harling Point in Victoria, B.C., deposited in the late 1930s. The metal box in the photographs below is one of the many unused boxes still stored at Portland's Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association. One end of each box was left unsoldered until used. For similar boxes in use in Hong Kong, click here.

"The Chinese population of the town of Chico, Cal., has for the past two weeks been under a strain of excitement concerning the exhumation and removal of all the bodies buried in the Chinese cemetery of that place. This has been a gruesome spectacle. A company of native resurrectionists dug Into the graves, took up the coffins, removed their contents and deliberately set to work getting rid of the more or less decomposed flesh, scraping the bones, drying them, then gathering them in bunches, carefully tied, wrapped, then labeled with the respective cognomens of the several deceased and the residence of the particular families in China ... (San Francisco Call 1893-11-14, p 19)

The decision-makers in such exhumation projects were usually Chinese organizations in large coastal cities--shantang (for individual districts), the huiguan (for groups of districts), and,after about 1900, the CCBAs (representing all huiguan). On the other hand, responsibility for excavating the bodies was less clear-cut. The Chinese sections of many and perhaps most cemeteries were controlled by the secret societies. They may have played a major direct or indirect role in handling one of chief difficulties that excavating the bodies involved, getting the necessary permits. Legal requirements and fees for exhumation varied widely from place to place, and it would have been almost impossible for either the big-city organizations or the traveling exhumation teams to have dealt with the necessary paperwork. For that, they needed help of the Chinese communities in or near the cemetery locations. In smaller inland places, this help would have had to be coordinated by the secret societies .

Yet the secret societies and others in the local communities seem not to have had more than an advisory role when it came time to open the graves and dig the bodies up. The shantang, huiguan, and CCBAs hired the specialists who would perform the exhumations and bring the bones back.

Harling Point in Victoria. Photo:Larry Wong 1959.

加拿大域多利哈宁角华人坟场储骨冢

How Exhuming and Repatriating Bones was Organized in San Francisco - Before 1930 之前三藩市怎样管理执骨, 洗骨, 运骨.

The Rev. A. W. Loomis, writing in1868 but already familiar with San Francisco's Chinatown in the 1850s observed that the repatriation of remains was not always so well organized: “The gathering of the bones of the dead and sending them back to China is not part of the work undertaken by these companies [huiguan]; but the people of different districts have in some instances undertaken separately the performance of this office [i.e., as shantang]; they have, however, selected the president of the company to which they belong to be their agent in the transaction of the necessary business and to receive and disburse the funds subscribed for the purpose. Only about half of the districts represented in California have sent home the bodies of their dead; but very many bodies are sent by personal friends here, or at the expense of relatives in China, independently of the aid of the organizations in this country for the removal of the dead.” Rev. Augustus Ward Loomis “The Six Chinese Companies.” Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine, vol 1, 221-227. 1868

Already in the 1850s organizations were being set up in San Francisco to oversee the return of the Chinese dead to China. The historian Him Mark Lai (2004: 72, 99, 114) observed that the Yeong Wo 阳和 and Sam Yup 三邑 associations were quick to settle on a system for repatriating bodies. Within a few years of arriving in California, migrants from each of the three Sam Yup counties had established shantang 善堂, with functions partly to exhume "the bodies of the dead and shipped them to China at regular intervals.”

County/Shantang

Date founded

Date founded

Panyu; Chong How Tong 番禺昌后 堂 1858

Lai (ibid.) states that several shantang charities under the Yeong Wo huiguan had come into existence and begun shipping bodies to China at about the same time. These may have included:

Xiangshan; Ji Shan Tang 中山集善堂 1880

Dongguan; Bao On Tong 东莞宝安堂 1868

Xiangshan; Hook Sin Tong 香山福善堂

Several other shantang charities, each representing one or more counties, began functioning somewhat later:

Zhaoqing-Hehe/ Quong Fook Tong 肇庆-合和广福堂 1896?

As time went on, the process became more centralized. While there must always have been rich families who could handle it themselves, in most cases, larger organizations were taking over. By the 1890s, English-language newspapers wrote as if that the huiguan, not the subordinate shantang, were playing a central role. In 1890, The Yan Wo 人和会馆 association [paid $500 for 59 disinterment certificates for bodies in the City Cemetery (San Francisco Call 1890-09-14). In 1888 the "Kong Chu" Company "sent its agent on a tour of the entire country to gather up the bones of defunct Chinamen;" the agent got as far as Brooklyn (New York Times 1888-07-10). In 1893, the Kong Chow 岡州 and Hop Wo 合和 associations not only paid for disinterment certificates but planned to ship 700 sets of bones back to China (San Francisco Call 1893-07-25; see also the New York Times 1893-05-18).

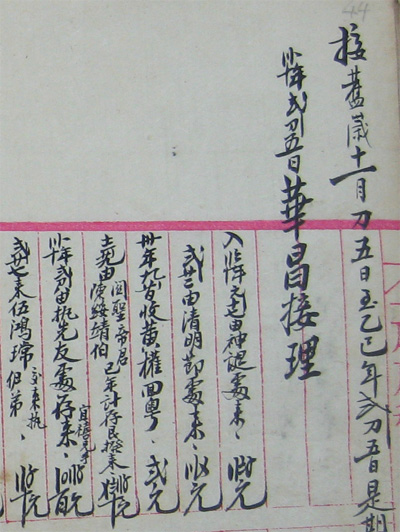

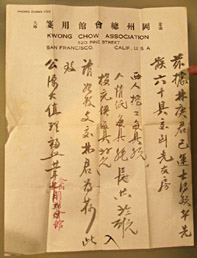

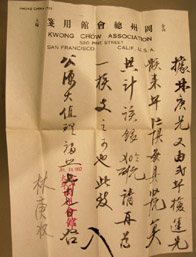

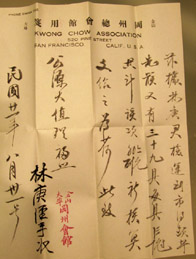

Some of the huiguan continued to handle the exhumation and collection of bones down through the 1930s. A fascinating series of previously unpublished records from the Kong (Kwong) Chow Association 岡州会馆 survives in the private collection of Philip Choy in San Francisco. Three are reproduced here. They represent bills to the Association from one Lin Geng 林庚 for bone collection and transportation services. Lin, one assumes, was a contractor rather than an actual exhumation specialist. He seems to have made a lot of money from his activities in spite of the fact that he had been associated with Kong Chow since at least 1918, used Kong Chow letterhead, and was living in a Kong Chow building.

Statement prepared by the Association

Bill for bringing 60 sets of bones to Stockton, CA. $780 Itemized as

-Western [White] diggers,

$5 x 60 = $300

-License, $0.50 x 60 = $30

-Packing?$7.50 x 60 = $450

Statement prepared by the Association, 7/18/1932.

to pay Lin Geng for having exhumed and brought 17 sets of bones from Sacramento to San Francisco, at $24/set = $408

Received and signed by Lin Geng

Statement prepared by the Association 8/31/1932

To pay Lin Geng for having brought 39 sets of bones to Stockton, at $13/set - $507

Received and signed by Lin Geng

Some of the more wealthy regional organizations and even clans continued to handle their own exhumations down through the late 1930s, when all shipments of bodies to China came to an end. Other huiguan and clans, however, seem to have gradually passed responsibility for exhuming and collecting to the increasingly powerful Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA), a.k.a. the Six Companies or Chong Wa.

On 11/1/1913, the Call reported that "The bodies of thousands of Chinese will be disinterred throughout the state for shipment to China within a few days under the direction of the Chinese Six Companies." On 6/20/1911, the same newspaper noted that the Six Companies had hired a lawyer to dispute San Mateo county's attempt to charge the Chinese community a $10 exhumation fee for each of 1700 Chinese bodies in a local cemetery, when the State Board of Health was already charging a similar $10 fee.

In Canada, exhumations were organized somewhat differently. From its founding in 1884 onward, the CCBA in Victoria not only owned and managed cemetery space but played a key role in digging the dead up and shipping them to China. In 1891 it not only persuaded the county associations (the equivalent of San Francisco's shantang) to set up a Committee of Bones Collection and Shipment, presumably the predecessor of the above-mentioned Canada Oversea Chinese Amalgamated Exhumation Board 加拿大华侨联邑执运先友 委员会, but became directly involved in the collection of Chinese bodies. In 1891 it hired men to dig up graves and retrieve bones from them along the Canadian Pacific Railroad tracks and in the gold mining centers of the Cariboo and Thompson River areas. According to David Lai(Chinese Community Leadership, 2010: pp 83-4) the CCBA paid "$4 for digging up a grave, cleaning the bones, the then packing them properly in a box. If the body had not completely decomposed, the retrieved covered up the grave again and was paid $2." This was cheap by Californian standards.

In and after 1937, more operational responsibility may have been delegated to the Amalgamated Exhumation Board. The document illustrated above shows that the Board was well-versed in Canadian law and customs, which must have made exhumations easier to arrange.

1938 application written by the Canada Oversea Chinese Amalgamated Exhumation Board, Victoria, BC . University of British Columbia Library Archives.

How Exhuming and Repatriating Bones was Organized in San Francisco and Victoria - After 1930 之后 三藩市, 域多利怎样管理执骨

Reference: CWBA records reproduced here with the permission of Dick Kay.

Registration by County, 1937.

Registration by Location: Montreal - No. 181. Li Jian-yong. Xinhui. Sponsored by Kong Chow Association

[Note: The above county names represent modern Pinyin spellings. In the 19th and 20th centuries they were usually spelled by North American Chinese according to their Cantonese or Taishanese pronunciation: Nanhai = "Namhoi", Panyu = "Punyu", Shunde = "Shuntak", Xiangshan = "Heungshan" (now Zhongshan = "Chungshan"), Dongguan = "Tungkun", Xinhui = "Sunwui", Xinning = "Sunning" (now Taishan = "Toisan"), Enping = "Yanping", and Kaiping = "Hoiping".

The huiguan names are given here in their Cantonese or Taishanese forms. The Pinyin equivalents are Hop Wo = "Hehe", Kong Chow = "Gangzhou", Ning Yung = "Ningyang", Sam Yup = "Sanyi", Si/Sze Yup = "Siyi", Yan Wo = "Renhe", Yeong Wo = "Yanghe"]

Storing the Dead Before Shipment: Bon Lee's and Larry Wong's Remarkable Photographs 绝无仅有的照片 - 王容伦拍的域多利贮骨所

San Francisco and Victoria both formerly had "bone houses" in local cemeteries where exhumed remains, packed ready for onward shipment, were stored for a few months until arrangements for sending the remains to China could be finalized. Such temporary storage places rapidly filled up after 1937, when first the Japanese seizure of Guangdong province and then unwillingness by the new Communist government to cooperate made it impossible to "repatriate" the exhumed remains to China. Not much is known about the bone house or houses in San Francisco. In Victoria, however, thanks to the strong interest of the local Chinese Benevolent Association (CBA) and the activist approach of Professor David Lai, the local civic authorities treated the problem of unrepatriated bones with real seriousness. The bones were given final burial in common graves within the cemetery. and the former bone house destroyed.

Until several months ago, the editors believed that no picture of any North American bone house was still in existence. So we were surprised when one of CINARC's corresponding editors, Larry Wong of Vancouver, showed us one. Sure enough: the bone house at Harling Point Cemetery. What's more, the photo was of the inside, not the outside, The following story is Larry's, reproduced with his permission

I was with a group of friends in my university year of 1959 and we visited friends in Victoria. Some of us thought it'd be cool to visit the cemetery in the (if you pardon the expression) dead of night. The window of the warehouse was high up and open, that is, it was a square opening, probably for ventilation. I had my camera with me and I was told there were boxes of bones ready to be shipped to China. The window was high up so I had to climb on someone's shoulder to peer through the dark opening. I managed to rest my elbows on the ledge and pointed the camera into the darkness. Only when the flash went off, did I glimpsed the wooden boxes. Not until days later when I had the film developed that I realized what I actually saw.

Harling Point., Victoria. The former bone house may have been in this part of the cemetery

加拿大域多利哈宁角华人坟场

Sign at Harling Point stating that in 1960 the contents of the bone house were moved into 13 common graves

Interior of Victoria's Bone House in 1959. This is the only extant photograph, taken at night by Larry Wong, as described here. Boxes ready for shipping are in the lower right corner.

Years later, when Wayson and I visited Dr. Lai I casually mentioned how I took a photograph of the boxes. He was astonished as no one had taken a picture of the interior. When I returned home, I sent him a copy.

Still later, a film maker visited him and he mentioned the photo to her. She emailed me and said she'd be interested in the image. I did and it showed up in her documentary, From Harling Point.

So the photo has a bit of a history, thanks to a middle of the night foray of the cemetery. And if I recall, I think it was on a dare!

A closeup of the bone shipping boxes appears above -- to see it, click here. In California, such boxes had to be made of metal. In British Columbia, they were made of wood.

Claimed Bodies: The Normal System for Reburying Bodies and Bones from North America in the Family Cemetery

入土为安 – 故乡是先友的终点站

When everything went as planned, the sets of bones and sometimes whole bodies in coffins) shipped from America would be sent onward by the Tung Wah Hospital to district organizations or clans in China which in turn would hand the remains over to the relevant family for burial.

A successful merchant and first president of Victoria's Chinese Benevolent Association, the first in Canada, Lee Yau Kan [Li Youqin], a.k.a., Lee Poon Yew and, in English-language newspapers, Lee Tow King and Lee Hon Kim, is a perfect example of the kind of person for whom the repatriation and reburial system existed. He had done well in his overseas career. Beginning his career as a merchant first in Hong Kong and then in Portland, he came to Victoria in the 1860s. His Kwong On Lung Co. on Comorant Street sold goods wholesale and was a major opium refiner (perfectly legal in those days). Lee gave generously to local charities in the 1860s through 1880s, and initiated the long, unsuccessful fight against the notorious Head Tax imposed only on Chinese Canadians. He was a founder and the first president of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association in Victoria 域多利埠中华会馆. He must have supported charities back in China as well, for the Qing dynasty government awarded him the honorary title of Imperial-Conferred First Class Sub-Prefect.

He had come from a small village in the Siyup area, Xiangbei hamlet, Shuilou village 水楼乡, Dajiang district 大江镇, Taishan county台山. At least one of his three wives and perhaps a son or daughter, may still have been living in Xuangbei at the time of his death. They and more distant relatives would have kept track of his achievements in the U.S. and Canada, and his financial success as well as the title given him by the Imperial government would have been a source of pride there in the home village. They naturally were more than willing to make room for him in the family cemetery, located only a few hundred meters away.

The editors do not know whether he was buried while still in the fancy Western-style coffin in which his body seems to have been shipped from Victoria (see below). But the modern residents of Xiangbei still know where his grave is, and continue to clear the area around it during the Qing-Ming Festival every spring.

Lee Yau Kan's Grave in Taishan 台山李祐芹墓

So his body was brought home to Taishan from Canada, in a full-sized coffin rather than a small box, and soon after his death without having been buried and dug up again. The English-language news sources do not indicate whether the CCBA, which he had helped to found only four years previously, was involved in arrangements for sending him back. The CCBA's assistance may not have been needed. Lee's firm had close connections in Hong Kong and Guangzhou, and would have been accustomed to handling shipments to and from those places.

He died on August 24, 1888. His funeral, a splendid one "owing to the rank of the deceased and the esteem in which he was held by his countrymen," was held on August 27. "The body was enclosed in a lead casing, the outer casket being of ebony, handsomely finished and mounted with silver. The plate bore the name, age, and date of death in Chinese characters." After ceremonies at Victoria's Ross Bay cemetery were completed, the casket with the body inside was "brought back to the city and stored away to await shipment to China."

Note: sources for Lee Yau Kan's life include issues of the British Colonist newspaper (see especially 1888-08-24, 1888-27, and 1888-08-31), and David Chuenyan Lai, Chinese Community Leadership 2010: p 52. Lai's information comes partly from his work with unpublished CCBA archival material now at the University of Victoria.

The editors located Lee Yau Kan's grave thanks to the directions given us by Myron Lee of Portland. He and his brothers, great-grandsons of Yau Kan, have okayed the publication by CINARC of images of Yau Kan's grave.

Xiangbei hamlet in 2011. Newer houses are on the right, older ones are straight ahead, and the village pond, a standard feature of communities in this part of Taishan, is on the left.

Lee Yau Kan's gravestone

Lee family cemetery at Xiangbei, Taishan

Reburying the dead from Harling Point's bone house in 1960. The wooden boxes in this common grave, one for each deceased person, are the same as those shown in the image below. Photo from Bon Lee; original now donated by him to the University of Victoria. Bon adds (in March, 2012) "The boy in the photo is my brother, Kent Lee. The offering used to be an annual event when we were young."

Usually the exhumed bones were stored temporarily by the relevant organization in the city from which they would be shipped to China. At least three cities, all ports with large Chinese populations, are recorded as having been used for that purpose: San Francisco, Victoria, and – interestingly—New York. There must have been more. As a subsequent article on Seattle shows, Chinese organizations in smaller cities also were able to handle at least part of the job of repatriating the dead.

Empty metal (galvanized steel with soldered seams) box for exhumed remains, in the collection of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, Portland.

钵仑 中华会馆储骨铁箱

Packing up the Bones in Victoria and Portland -- Why Metal Boxes? 域多利, 钵仑怎样装载骨殖?

Apparently each set of excavated bones was placed in individual containers and carried to a temporary store place designated by the organizing association, ready to be shipped to Hong Kong. By late 1920s the standard packing material was a tin box encased in a wooden box. But some associations packed bones with other materials which proved to be impractical. In a 1928 letter to Yu Hing Tang of the Ning Yung Benevolent Association 宁阳会馆 馀庆堂 in San Francisco, the Tung Wah 东华医院 Hospital in Hong Kong complained:

“… your office sent bones in cloth bags. These bags have rotted and caused much chaos. When people came to claim them, it was not possible to identify individual sets correctly. .... Our hearts have no peace. It is known to us that other ports send each set of bones in a zinc [white iron] box, which is encased in a wooden box and is handwritten with the deceased’s name and hometown on it. They also send a separate list of names to us for easy reference. This has been a very reliable system. We beg your office to follow this practice ….”

References: We thank Victor Leo of the Portland CCBA for permission to photograph the metal boxes and to share the information.

-Tung Wah Hospital Archives - External Correspondence 1927-1928. Published in Yip Hanming (2009). Tung Wah Charitable Cemetery and Its Global Connections: information based on archival materials. pp. 193-194. 叶汉明. 东华义莊与环球慈善网络: 档案文献资料的印证与启示.

- Sam Yup benevolent Association History Editorial Committee (1999). A History of the Sam Yup Benevolent Association in the United States 1850-2000, pp. 287-88. 旅美三邑总会馆史略

Rules for Digging up the Dead - San Francisco 三藩市怎样管理执骨, 洗骨?

Appendix: Modes of Retrieving Deceased Bones - 18 Components

[附记检先骸骨式 – 计有十八样]

.. Skull - one piece. Pigtail - one. Lower jaw - one.

.. Cheek bones - one complete or three broken pieces

.. Chest bones - one complete or two broken pieces

.. Neck bones - 24 or more pieces

.. Ribs - nine to ten pieces on each side

.. Shoulder bones - 13 pieces on each side

.. Shoulder blades - one on each side

.. Upper limbs - Arms: 3 bones each side; Wrists: 8 small pieces each side; Hands: 19 pieces each side

.. Lower limbs - Hip: one bone each side; Legs: 3 on each side; Knee - one on each side; Ankles - 7 small pieces;

Responsible supervisors and workers should follow this list, search carefully, and don't be casual about it. Be mindful,

be mindful."

Reference: Sam Yup Benevolent Association History Editorial Committee (1999). A History of the Sam Yup Benevolent Association in the United States 1850-2000, p.95. 旅美三邑总会馆史略

Chong How Tong cemetery at the Chinese Cemetery, Daly City for deceased of Panyu County, Guangdong.

六山 坟场 番禺昌后堂墓地

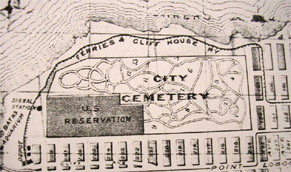

Left: San Francisco City Cemetery, 1898. Now the park at the Palace of the Legion of Honor art museum. All burials were removed long ago. The Chinese burials were at Numbers 7, 8, and 9 (click to enlarge). 三藩市坟场平面图

Right: Chinese Cemetery run by the Chinese Six Companies in Daly City, CA) 六山 坟场一景

| ||||

It made sense for a single, neutral organization to take over the collecting and onward shipment of Chinese remains. Back in the 19th century, although exhumation specialists and their employers undoubtedly found it profitable to bring back as many sets of bones as possible, regardless of regional affiliation, members of the Chinese public must have found this problematical. How could the Sam Yup huiguan be certain that a Si Yup organization, like the above-mentioned Kong Chow huiguan, would take proper care in exhuming Sam Yup bodies?

Left: Quong Fook Tang Memorial.

Right: Ji shan Tang Memorial.

Chinese Ceme-tery, Daly City, CA

左: 广福堂

右: 集善堂

六山 坟场

"The lady is my aunt and the photo was taken by my Uncle George Reynolds who was adopted by my

Great Grandmother. He helped arrange at least 1 shipment of bones from Portland to Tung Wah in the 1940's. Their

letter states they found at least one box that was labeled by my Uncle and was being stored in Hong Kong as the

communists did not allow the bones to be relayed further. If one of the photos contain the remains of the some people

from Portland, it would be interesting to find out where they are now."

The boxes on the right all contain the remains of persons with the surname Huang/Wong whose home villages were in Taishan/Toisan in the Siyap (now Wuyi) area of Guangdong province. The Coffin Home has sorted and stored the boxes by district, village, and family name to facilitate their eventual return. Commenting on the above picture, Jeff suggests "I might guess the box Mrs Reynolds is pointing to is the Wong from Portland with George's hand writing and instructions."

The Interior of the Tung Wah Coffin Home

俄勒岗州钵仑先友- 香港东华义庄

Metal boxes, like those shown in a preceding section, each held the remains of one individual. As noted above, by 1960 the bones of more than 8000 exhumed individuals had accumulated in Tung Wah's Coffin Home, waiting to be returned to the home villages of those individuals. Bones from he United States were still in their original metal boxes.

In recent years Chinese American families have shown much interest in the coffin home, hoping to find the bodies of ancestors and other relatives. One such family was the Yarnes of Portland. These pictures come from Jeff Yarne of that city. They appear here with his permission. Jeff writes:

Mrs. Reynolds with bone boxes in the Tung Wah Coffin Home 东华义庄储骨殖室一角

Others with the same specialty included Hong Too, the "general bone gatherer for the Sam Yup Co.," who in 1886 visited Astoria, Portland, and The Dalles (all in Oregon) in the course of his regular rounds of cemeteries where Chinese had been buried, and the representative of another unnamed "Chinese Company" who also came to Astoria in 1886 for the same purpose. [quotes are from the Weekly Astorian 1886-08-14 and the Daily Astorian 1891-06-10, as cited by Chris Friday, 1994, Organizing Asian-American Labor, pp 63-4]

A Lone Voice Spoke Out in Canada: Bone Repatriation Was Harmful

孤掌难鸣 - 加拿大读者敢言执运先友害处多

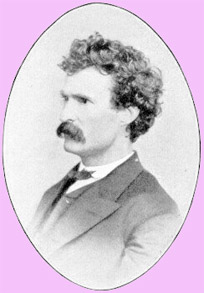

Before 1940, all overseas Chinese communities were deeply involved with organizing the exhumation and repatriation of the bodies of their countrymen. Their involvement was so deep, in fact, that it could become an almost overwhelming financial and administrative burden. Informed constantly that it was a sacred duty, even small, poor communities devoted more time and money than they could afford to ensuring "homecoming" after death.

- 1. It drains away economic resources from overseas Chinese communities. The cost of each repatriation project can add up to several thousands. If one uses the money to invest in schools then students can benefit. Investing in building a hospital benefits the patients and their families and friends. Now we spend the money on the dead who have no way of knowing any benefits.

- 2. It hurts the families of the deceased. Each family has to bear such expenses as paying for a re-burial spot and for maintaining it year after year.

- 3. It lowers productivity. Farm land should be utilized as an economically productive resource. If only the less fertile land is used for burying the dead then at least the impact is less damaging. But reserving acres of agricultural land for burial purposes can hurt the economy badly.

- 4. It does not let the deceased rest in peace. If the spirits of the dead are unable to feel anything, then at least they will be numb to repeated disturbances. But if they can actually feel, how much trouble they must have experienced! What if any of the over 200 pieces of bone gets lost on the way?

- 5. It hinders the growth of China. Let us consider Guangdong first, which is very overpopulated. The government wants to discourage superstition and to open up more land for agricultural purposes. Now instead the land is used to accommodate thousands of sets of bones returned from abroad. Manipulated by evil landowners, uneducated villagers who long to rebury the returned bones have not been helping to advance the government’s progressive policies.

- 6. It breaks down families and endangers clans. In China there have been much violence and many lawsuits due to disputes over reburial issues. Well-understood effects include bankruptcy and deaths. Such efects actually could have been avoided. Why is that? Families misuse their wealth. Local landowners take away their land under the name of charity. Disputes often follow and resolutions are attempted through use of violence or legal procedures. Bad feelings can go on for generations.

Tai Hon Kong Bo's editor added: "Zu De’s opinions speak for my mind. I would just add this: In oppressing Chinese, white people often claim that Chinese can never be assimilated, citing the bone repatriation as an example. So it is obvious that the custom does not have much benefit for Chinese here. My humble opinion is that the once-every-seven-year bone repatriation custom does not have to be seen as a law. If families are in agreement and willing, then repatriation can be done. Otherwise, the deceased should stay [here in Canada], including those without hometown addresses. Why disturb the dead and burden the living?"

Scarcely anyone dared to object. That is why an op-ed piece by one Zu De 祖德 (seemingly a pen-name, perhaps the editor himelf), published on May 29, 1928, in Vancouver's Chinese-language Tai Hon Kong Bo 大漢公報 (Pinyin Dahan Gongbao) newspaper, was unusual as well as important. "Zu De" gave six reasons why exhuming and repatriating Chinese bones should stop. Here the reasons are translated into English:

Two sketches from the Chicago Tribune (1893-12-07): "Disinterring the Bones of Chinamen" & "Dipping the Bones" [to preserve them]

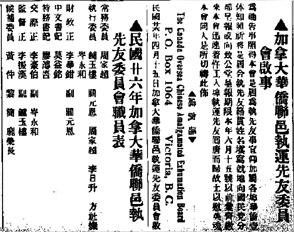

How Exhuming and Repatriating Bones was Organized in Canada

加拿大执运先友善堂

The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) in Victoria was involved very early in bone-repatriation projects. In 1885 its founders stated that one of its main tasks was to continue collecting and returning the bones of the deceased from everywhere in Canada to their home towns in China. But the Association was only peripherally involved in repatriating the dead until 1937, when it finally began to play a more active role.

Repatriation was usually run on a 7-year cycle. As the process required multiple levels of cooperation, Chinese communities in Canada received notices and progress reports from the relevant huiguan (county organizations) a year or so ahead of the shipment schedule.

As was the case in San Francisco, almost every county from which immigrants came was represented by a separate huiguan, with headquarters in Victoria - some eventually shifted to Vancouver. Most county organizations had a subsidiary shantang, a charity branch, for repatriation purposes. Some hadn't, an indication that those particular county populations in Canada lacked size and strength.

1. Taishan/Ning Yang County [Yuqing Tang]

Ning Yung Yee Hing Tong 宁阳余庆堂

2. Xinhui County [Fuqing Tang]

Sun Wei Fook Hing Tong 新会福庆堂

3. Xiangshan/Zhongshan County [Fushan Tang]

Hook Sin Tong 香山福善堂

4. Kaiping County. [Guangfu Tang]

Hoy Ping Kwong Fong Tong 開平廣福堂

5. Pan-yu County. [Yushan Changhou Tang]

Pon Yup Chong Howe Tong 番禺昌后 堂

6. Zengcheng County [Ren-an Tang]

Ying On Tong 増城仁安堂

7. Dongguan County [Bao-an Tang]

Tung Goon Bo On Tong 东莞宝安堂

8. Shunde County [Xing-an Tang]

Hung On Tong 顺德行安堂

9. Nanhai County [Fuyin Tang]

Namhoi Fook Yum Tong 南海福蔭堂

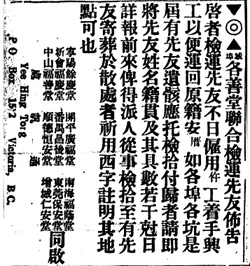

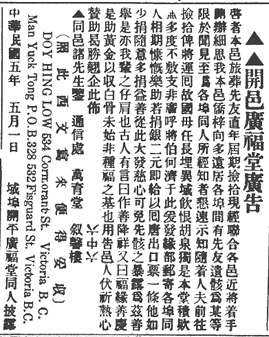

In May 1916 eighteen huiguan put out a joint announcement in Tai Hon Kong Bo 大漢公報 :

In theory, each county huiguan was responsible for the cost of exhuming and repatriating the dead from that county. The funding came from a $2 "China-returning fee" collected from members. As actual repatriation costs were much higher, $2 would only be enough if very few members died in Canada. Sometimes smaller county organizations simply could not afford to pay. In December 1925, for instance, only 9 of the 18 county associations from the 1917 announcement were still willing to participate in the repatriation process, as this advertisement in Tai Hon Kong Bo indicates.

The Canadian Chinese community finally began to cooperate fully on repatriation in 1937. In that year a Victoria-based Canada Oversea Chinese Amalgamated Exhumation Board 加拿大华侨联邑 执运先友 委员会 was formed. It had a committee of 18 persons, many were also directors of the Victoria CCBA. Interestingly, rather than utilizing county associations for primary contacts outside Victoria and Vancouver, the committee planned to work in partnership with the Kuomintang political party and the Chee Kung Tang secret society.

The moving force behind the 1917 announcement was not the CCBA but the Ning Yung (Taishan) Association, which took the lead in organizing every cycle of repatriation before 1937. The Ning Yung Association also paid in advance for the expense of getting permits, digging, and assembling bones for shipment. It received reimbursement from other associations later, and sometimes found these difficult to collect. Even the CCBA, for instance, was unable to repay Ning Yung for expenses incurred in exhuming and shipping unidentifiable Chinese remains. .

The Zhongshan Association's Fushan Tang

Building, one of the landmarks of Victoria's

Chinatown. For more details click here.

域多利香山福善堂

Panyu County's Yushan Association in Victoria. Its charity arm, Changhou Tang, reported financially, in 1919 at least, to the Changzhou Tang in San Francisco.

域多利 番禺昌后 堂

In that year the Committee recovered about 1500 sets of bones but was unable to forward them to Hong Kong due to the Sino-Japanese war. The bones were stored at a wooden hut at Harling Point Cemetery, Victoria. In June 1946 the Ning Yung Association put out an ad in Tai Hon Kong Bo to launch a $20,000 fund-raising campaign with the hope of sending those bones off to China. It did not happen. Today Harling Point is the permanent resting place of those 1937 repatriation individuals, reburied in 1961 in groups according to their county affiliation. For more data and photos on Harling Point bone storage, click here.

The Canada Oversea Chinese Amalgamated Exhumation Board, Victoria: "We pray [you] to write down names and hometown affiliations of those eligible deceased, and report them to your local branch of the Kuomintang or the Chee Kung Tang, before the June 15th deadline....."

Chinese Benevolent Association,

Victoria.域多利中华会馆

Natives of Kaiping County Natives of Zengcheng County Natives of Xinhui County

"Together with the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, the county associations will start work on a new cycle of bone repatriation project. The expenses for the deceased with no identifiable home town will be born by the CCBA. This announcement is to notify our countrymen to report to us the eligible deceased and those we missed in the last cycle. We can follow up and recover their bones. Please give the project your attention. Together we are creating endless merit." [signed by the following:]

The Ning Yung (Taishan) Association, Victoria

域多利宁阳余庆堂

Announcement in Dec 27, 1925 issues of the Vancouver newspaper, Tai Hon

Kong Bo 大漢公報

MARKERS ON MASS GRAVES AT HARLING BAY 域多利哈宁角华人坟场

10. Enping County [Tongfu Tang]

Yan Ping Hong Fook Tong 恩平同福堂

11. Xinan County [Tongshan Tang]

新安同善堂

12. Heshan County. 鹤山县

13. Yangjiang County. 阳江县

14. Xinxing County. 新兴县

15. Yangchun County.阳春县

16. Gaoyao County. 高要县

17. Gaoming County. 高明县

18. Sanshui County. 三水县.

Note: county names are in black, and the corresponding shantang [charity branch] names in purple; most of the shantang bear the same names as their counterparts in San Francisco. Their pinyin spelling appears on the first line and local spelling on the second.

Tai Hon Kong Bo 大漢公報 (Chinese Times), Victoria, May 10, 1937.

How to Tell Whose Bones They Were: A Solution from Alaska

亚拉斯加出土1904 台山海宴人墓砖

It was essential for the exhumation team to identify the body accurately. For that an above-surface grave marker, easily vandalized or moved, was obviously inadequate. So too, of course, were the fallible memories of local Chinese residents. The best solution was to bury identifying information in the grave along with the deceased.

That was the function of this inscribed brick from Alaska, with Chinese characters written with brush and ink. It was donated to the Alaska State Museum by the finder who obtained it at Karluk on Kodiak Island, formerly the home of several big salmon canneries with many Chinese workers. Three of the canneries were owned by Alaska Packers Association, a San Francisco firm that hired workers for Karluk from several San Francisco labor contractors. Thus, the deceased, Luo Ben 羅本, may well have lived in or near San Francisco. The inscription states that Luo was a native of Haiyan 海宴 in Ningyang (now Taishan) county, and that he died in 1904.

Sue Fawn Chung, a University of Nevada-Las Vegas archaeologist who has excavated a number of Chinese burials, comments "These bricks were found in many Chinese cemeteries throughout the West. The Alaska brick resembles the ones found in Carlin [Nevada] (there were several). The bricks were an important means of identification and the information was reproduced on the boxes/containers that were sent to San Francisco or China for burial." [for a photo of a Nevada example, see Sue Fawn Chung & Priscilla Wegars, Chinese American Death Rituals, 2005: page 134]

Priscilla Wegars of the Asian American Comparative Collection at the University of Idaho, adds : "These are others that I know of . . . Forbestown, Calif., museum; Queensland, Cooktown, Australia, James Cook Historical Museum; Queensland, Croydon, Australia (brochure for archaeological site); another 1 or 2 from

California - photos from [Wendy] Rouse [for another image of an incised rather than painted brick from a California cemetery, see Rouse's article in Chung & Wegars, p 96]. CADR [the same book] p 156 mentions other burial markers besides bricks (e.g., wooden slats or cloth strips in bottles.) It also mentions burial bricks from a SF cemetery and from Weaverville, CA, in addition to the Forbestown brick."

Burial brick from Karluk, now in the Alaska State Museum, Juneau.

Such bricks must have been discarded once the information on them had been transferred to the bone box before sending to San Francisco or other port for shipment onward to Hong Kong. Putting a brick into the box before shipping woud have risked crushing the bones.

The Karluk brick was presented to the museum by.Everett Watrous and was kindly shown to us by the museum's curator of collections, Steve Henrickson. While the photo is ours, the diagonal line indicates that we do not yet have the ASM's permission to include it on this website. Information on Karluk comes from the annual reports of the Alaska Packers'Association as preserved in the Alaska State Archives.

(UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED ALL DATA ON THIS PAGE COMES FROM THE EDITORS' OWN RESEARCH ON PRIMARY SOURCES & ARTIFACTS)

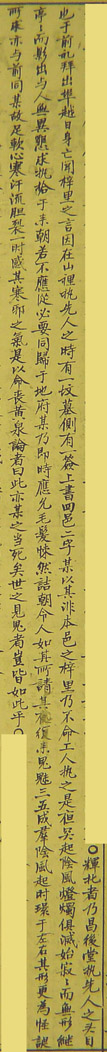

Fei Buk (pinyin: Huibei), the head of a bone retrieval team for the Panyu County Chong How Tong [a shantang--see below], who left town last week, has died. We heard from fellow countrymen there that while he was recovering the bones, he encountered a tomb with a sign saying that its inhabitant was from Siyup. Fei Buk, knowing that this individual did not belong to his county, gave orders to his workers not to disturb the bones. But that night, a strange wind came up and blew out the lamp, after which there was dead silence and a human shadow. And that shadow asked to have his bones collected the next day. If Fei Buk refused, there would be consequences.

He immediately agreed. The next day, he asked his workers to comply with the shadow's request. But that night, several more spirits appeared. Even more terrible looking, these demanded the same thing. Fei Buk’s heart was frozen. Sweat streamed down his body. Then his gall bladder burst.

It was later said that all these evil inhuman spirits had probably caused him to lose his life, and that Fei Buk had been fated to die. Indeed, most people do not run into spirits like this.

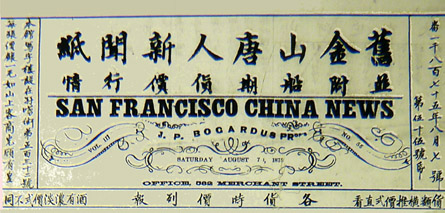

(Panyu is one of the Samyup counties and, in early California, not on friendly terms with people from the Siyup counties.) Translated by the editors from San Francisco China News, 1875-08-07

The Perils of Exhumation: A Ghost Story 番禺昌后堂執骨工头遇鬼

By the mid-1870s, most of the home-county associations or huiguan had accepted responsibility for sending out specialists to exhume the bones of deceased Chinese from cemeteries all over the western U.S. and Canada in order to ship those bones back to China. As this contemporary newspaper story shows, each county association handled only graves of persons from that particular county. As the story also shows, bone gatherers needed not only diplomacy and anatomical knowledge but also ritual expertise. Even for those who had mastered the necessary rituals, the job could be highly dangerous.

The following news article illustrates Chinese feelings on the subject,

Masthead of 1875-8-7 issue of the Chinese-language San Francisco China News. Only a single (1874-12-26) issue of the weekly SFCN is available on line. This issue, which has not yet been put on line, is from Philip Choy's private collection.

The ghost article in the San Francisco China News, 1875-8-7

This page was last updated: August 30, 2018

Why Did They Repatriate the Bodies? 何必如此辛苦经营?

The ostensible reasons were, first, the need to ensure that one's family--ideally one's sons and grandsons--would be able to make sacrifices at one's family altar and to maintain one's grave in the family cemetery, and, second, the belief among Chinese that one had to be buried in the homeland, whether or not one's family would or could care for the grave.

There is a problem with this explanation, however. In Southeast Asia, which in the 19th century had many more Chinese sojourner-immigrants than North America and an equal scarcity of locally resident Chinese families, many and perhaps most Chinese were not repatriated. Even though wives and children had stayed back in China, the deceased were often buried on the spot in Southeast Asia. Some indeed were repatriated. And yet the early Chinese cemeteries in Southeast Asia, some of them very large, show few signs that large numbers of bodies have been exhumed and returned to China. Most graves are still in use, and many date to the 19th-early 20th centuries. The Cantonese Cemetery in Penang, while in the middle or re-structuring, still had many tombs of the early 19th century when editors visited the cemetery this summer.

Bukit Brown Cemetery, Singapore

(Fujianese).

新加坡.武吉布郎.坆场.(福建墓地)

Mt. Erskine Cantonese Cemetery, Penang, Malaysia. 马来西亚.槟城.白云山.广东墓地

Guangdong Cemetery, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 马来西亚.吉隆坡.广东义山

So why was repatriating bodies so imperative in North America and so non-essential in Southeast Asia? We do not know. One explanation, offered by officers of the ancient Ningyang Huiguan in Singapore (which dates to the 1820s), when informed that San Francisco's Ningyang Huiguan (which dates to the 1850s) had formerly had repatriation as one of its main functions, was that their own huiguan had never been involved with digging bodies up and sending them back to China because it was just too expensive. Another explanation is that the urgency of the need to be buried in China rather than abroad was emphasized and perhaps exaggerated by North American district huiguan and CCBA's (Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Associations) in order to attract contributions from local Chinese.

In the case of Malaysia, it is possible that British colonial regulations prevented local Chinese from repatriating remains. This is implied by two 1930s letters from the archives of the Tung Wah Hospital. Both letters, one from Tung Wah to Singapore and the other from Kuala Lumpur to Tung Wah, discuss setting up bone repatriation systems that may not have existed previously. On the other hand, letters from the Philippines, Thailand, and Indonesia (then the Dutch East Indies) make it clear that there were no legal obstacles to shipping human remains to Hong Kong from those countries. Such remains seem not to have been shipped in large numbers, however. Proportionally speaking, Southeast Asian countries repatriated many fewer Chinese remains than did the United States and Canada.

Statement by a Canadian Shantang, 1916 加拿大开平人办捡骨的理由

That certain huiguan and their affiliated shantang treated repatriation in terms of urgency is shown, for instance, by a notice that appeared in Vancouver's Tai Hon Kong Bo' 大漢公報["Chinese Times"] in 1916:

“Guangfu Tang of Kaiping District, Announcement.

“Be notified: The bones for deceased individuals from our district are due for re-packing [i.e., exhumation and packing for repatriation] this year. We have already contacted other localities to start the process. Fellow district people have lived in various [Canadian] cities and far-away towns and some have been buried there. We are not well informed where those burials are. We sincerely hope that those who know will notify us soon. We will follow up by sending people to dig up and pack those bones so that they can be sent back to their old country, not buried forever underground, swallowing bitterness from a foreign spring. However, our shantang is short of funds and cannot afford all the expenses. We appeal here widely for contributions. We will send our donation books to various cities and towns. Those who give two silver dollars can get a Return Ticket to China. It is up to donors to contribute as little as they please, or as much as they can. This great generosity can help to keep the bones of the deceased from being exposed. Such charitable acts must be borne on the shoulders of our generation. There is an old saying that kind acts will be endowed with auspicious fortune. Another saying is that good karma and charitable celebrations will build up gold. Helping to help collect white bones undoubtedly builds a foundation for good fortune…” Victoria, B.C.,1916-05-16

Ref: Letters at Tung Wah Hospital, see Yip Honming (2009). Tung Wah Charitable Cemetery and Its Global Connections: information based on archival materials. pp. 250-251. 叶汉明. 东华义莊与环球慈善网络: 档案文献资料的印证与启示. 250-251 页