HISTORY

This page presents data on selected aspects of the Chinese presence in the Northwest, arranged chronologically

Ships and Early Chinese Visitors

1785 The first named Chinese actually to reach the continent:

1788-89 The first Chinese in the Pacific Northwest:

1788 The first Chinese in Washington State [07/22/09]

1906 The Chinese crew on the Great Northern's super-ship [03/01/09]

Chinatowns

1844 The First "Chinatown" [Updated 09/05/11]

Misc. Events

1880s Joking about the Murder of Chinese at Deception Pass [Updated 07/18/11]

1885-87 Outbreak of Anti-Chinese Violence in the Northwest [Updated 09/01/09]

1903 The Seattle chapter of the Baohuanghui is founded [Updated 07/29/09]

1906 The Visit of Prince Tsai and the Imperial Commission [Updated 07/22/09]

版权 Copyright is free for non-profit use:

1788 The first Chinese in

the Northwest?

1789 Martinez, captor of the first Chinese

1906 The great ship Dakota with a 50% Chinese crew

1906 Local boy makes speech to Prince Tsai

1903 The Preserve-the-Emperor Assn. comes to Seattle

1880s Deception Pass: Joking about Chinese murdered by smugglers

1906 Prince Tsai & Commis-sioners: Chinese merchants gain status

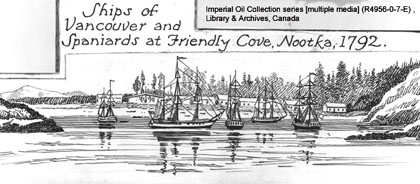

1788-1789 The first Chinese in the Pacific Northwest?: Affee and Aehaw with John Meares at Nootka Sound

We may eventually learn otherwise once researchers have gone through crew lists of merchant ships preserved in British and American archives [1]. For now, however, the first named Chinese individuals to reach this region seem to have been two seamen who served with John Meares in his voyage to Vancouver Island in 1788-89, Affee (Ah Fei?) and Aehaw (Ah Ho?) [2]. The “Ah” prefix shows that both were ethnic Cantonese. They belonged to a group of 50 Chinese who had come with Meares from Canton and Macao. Affee and Aehaw were assigned by Meares to help man a small ship, the North-West America, that had just been built on Vancouver, mainly by Chinese shipwrights. Its mission was to trade along the coast for sea otter furs and to take those for sale to China.

Meares had left Canton [Guangzhou] with two British-built ships, the Felice and the Iphigenia. He wrote: “The crews of these ships consisted of Europeans and China-men, with a larger proportion of the former. The Chinese were, on this occasion, shipped as an experiment: – they have generally been esteemed an hardy, and industrious, as well as ingenious race of people; they live on fish and rice, and, requiring but low wages, it was a matter also of oeconomical consideration to employ them; and during the whole of the voyage there was every reason to be satisfied with their services. – If hereafter trading posts should be established on the American coast, a colony of these men would be a very valuable acquisition.” [3]

These Chinese were skilled workers rather than mere coolies, and all were volunteers: In Meares’ words, “A much greater number of Chinese solicited to enter into this service than could be received; and so far did the spirit of enterprise influence them, that those we were under the necessity of refusing, gave the most unequivocal marks of mortification and disappointment. – From the many who offered themselves, fifty were selected, as fully sufficient for the purposes of the voyage: they were, as has been already observed, chiefly handicraft-men, of various kinds, with a small proportion of sailors who had been used to the junks which navigate every part of the Chinese seas.” [4]

A second group of Chinese in Colnett's Argonaut, another ship owned by Meares, were captured by the Spanish warships Princesa and San Carlos, and forced to build fortifications and then to work in mines. [5] These eventually either returned to China or stayed in Mexico. All were accounted for, Despite various speculations, it seems unlikely that any of the Chinese in Colnett's ship married indian women and settled down in the region that later became British Columbia, Washington State, and Oregon.

This entry has been adapted from a webpage written by the current editors, from the website of the Chinese-

American Museum of Chicago <http://www.ccamuseum.org/research1>

[1] [http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/catalogue/RdLeaflet.asp?sLeafletID=130&j=1].

[2] Meares, Voyages, Appendix X.

[3] Meares, John. Voyages Made in the Years 1788 and 1789 from China to the North West Coast of America. London, 1790, page 2.

[4] Meares, ditto, page 3

[5] Meares, Voyages, Appendices I and X

Several other European ships sailing from East Asia to the Northwest Coast in the 17809s and 1790s also had or may have had Chinese crew aboard. A list of those ships is included here.

The first Chinese in the Pacific Northwest: Does this picture show them?

第一个批到北美洲西北角的华人

The editors have ben told that one illustration in Meares' book, the image of the launching of the North West America, actually depicts Chinese. To check on this, we scanned that illustration in a first edition of the book, from the library of the Field Museum in Chicago. As far as we can see, although the illustration shows the ship and a building, both of them made by Chinese craftsmen, the only people it shows are Native Americans and Englishmen. A closeup of the relevant image is included below so that you can check for yourself.

Could any of these figures be Chinese? Perhaps wearing items of local Indian clothing? The ship and the house both had been built by Chinese craftsmen. The artist knew this. His author, Meares, was promoting the idea of bringing more Chinese to the Northwest Coast. So why would he have left the Chinese out of the picture?

Closeup of ship launching scene from Meares'Voyages. Click here to see a detailed version

The launching of the North West America at Nootka Sound, Vancouver Island. From Meares' Voyages, 1790.

1785: The First Named Chinese in North America 第一个到北美洲的华人

According to the excellent Asian North American Timeline Project posted on one of UBC's websites, the first were three seamen, Ashing, Achun and Aceun, who on August 9, 1785 were stranded in Baltimore by John O'Donnell, the captain of the ship Pallas. The Maryland Journal (Baltimore, August 12, 1785) reported that, 32 Asian Indian sailors ("Lascars") were stranded by the same ship. As in the case of John Meares' employees, the "Ah" prefix to the Chinese seamen's names shows that all were Cantonese. What happened to them afterward is not known.

There probably were other Chinese who came even earlier as crew members of ships trading between America and Asia, but no records of their presence have as yet come to light. There must also have been Chinese among the many "Filipinos" who served as crew on board the Manila Galleons that sailed each year between Mexico and the Philippines from the late 16th century onward. Again, however, no identifiably Chinese names have survived.

Prince Tsai Tseh in Seattle, 1906 晚清出洋考察大臣: 镇国公戴泽抵西雅图

On February 28 1906, three Imperial Commissioners led by Prince Tsai Tseh (Dai Ze, 戴泽), a favorite of Dowager Empress Cixi, arrived at Port Townsend and Seattle en route to the East Coast. The Tsai Tseh group was part of the well-known "Five Ocean-going Officials"; the first group led by Tai Hung-chi and Tuan Fang a month earlier came through San Francisco instead. Tsai Tseh's two-day stopover in Seattle was the highest-level Chinese visit to that city made thus far, and would remain so for decades to come.

The three commissioners and their 35 assistants were given a lavish welcome when their steamship, the SS Dakota, pulled in. Judge Thomas Burke, I.A. Nadeau, and Chung Poo Hsi (鍾寶僖), Chinese Consul at San Francisco, led the reception party of Chinese and white Americans that walked up the gangway to meet the three Chinese commissioners. A temporary welcoming arch with bright Chinese characters, sponsored and built by local Chinese-Americans, stood at the landward end of the pier. The Great Northern Railroad Company, which owned the Dakota, graciously invited the whole welcoming party to come up and join the three commissioners and their assistants for breakfast, before continuing on to Seattle and the Hotel Washington where the group would stay.

The visitors were part of what in Chinese was called “The Five Great Officials Touring Oceans” program, a major progressive effort by the normally unprogressive imperial government of China. In an effort to learn from the West, the Prince’s group was assigned to focus on education systems in Japan, American, and Europe.

On the second evening of their visit, while the Prince rested, the other two commissioners, Shang Chi Hong (Shang Qiheng 尚其亨) and Li Sheng Te (Li Shengduo 李盛鐸), made an extraordinary move. They attended a meeting of the Baohuanghui, the China Reform Society, regarded as subversive by the Imperial government. What is more, they accepted and promised to take back to China a joint petition from the presidents of the Portland, Seattle, and Victoria branches of the Baohuanghui. The petition was political dynamite. It demanded the abdication of the elderly but all-powerful Dowager Empress. Evidently, the Commission had a secret agenda that was quite different from its official mission.

Judge Burke, Mayor Ballinger, I. A. Nadeau, and their fellow European-Americans naturally had no inkling of this. To them, the occasion was a normal, if very high-ranking, state visit by dignitaries from a country with which they hoped to promote trade. However, the secret agenda of the Commission had one effect that must have been visible to the white elite of Seattle – it was evident that the leading Chinese businessmen of the Northwest were treated with respect by highly placed Chinese officials. Contemporary Americans often claimed that the Chinese who came to the United States were no more than coolies, despised by the educated upper classes back in China. And yet here were American Chinese who evidently were not despised at all. Even the Prince would talk to them, although perhaps a bit condescendingly, and the other two commissioners, one a former cabinet minister and the other a veteran ambassador, associated with local Chinese in quite a friendly way.

L-R: Shang Chi Hong, Prince Tsai Tseh, and Li Sheng Te

(for image data see Note 1 below)

Imperial Commission Events and Future Leaders for the AYPE

出洋大臣導致赛会领袖出位

On their first day in Seattle, February 28, the commissioners were taken to see the University of Washington, where they were welcomed by Dean Priest and Judge Hanford. Dr. Kane, the president of the university, gave a speech and the college band played music from Gilbert and Sullivan's “Mikado” – China, after all, was not far from Japan. Later, at the Commissioners’ request, the students demonstrated “yelling,” which presumably was coordinated cheering of the kind practiced at football games. Lew G. Kay (刘吉祺), the first Chinese student to enter UW, was scheduled to give a speech that evening at a banquet for the Prince and his party.

The banquet was held at the old Washington Hotel, hosted by local Chinese individuals and business organizations and by the Seattle Chamber of Commerce. Among those present were 27 Chinese from Northwest communities plus numerous white dignitaries, including Mayor Ballinger, Dr. Kane, the University of Washington president, Judge Thomas Burke and I.A. Nadeau, who three years later would become Director General of the AYPE.

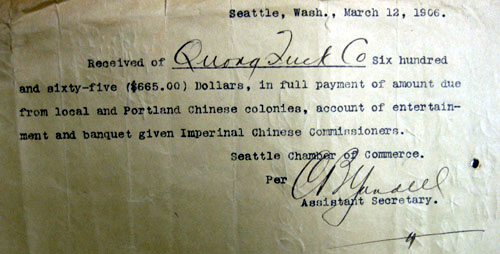

Arrangements were coordinated by the Chinese Consolidation Benevolent Association (CCBA) and the Seattle (white) Chamber of Commerce. Records of the Association, which at that time was managed by the Quong Tuck Company, show that it paid the Chamber $665 for its share of the banquet expenses. Each of the local Chinese who attended the banquet paid $75 for the privilege. Among these were Ng Hok Moy (a.k.a. Ah King) and Lew King, a well-respected merchant in Seattle since 1874 and the father of Lew Kay. Although Lew Kay’s name did not appear on the guest list, he was invited to attend the banquet as a speaker. Significantly, both Ah King and Lew Kay were to play central roles in the Chinese celebrations at the AYPE in 1909.

According to the Seattle Times, three local Chinese gave speeches in English at the banquet, led by the vice-consul in San Francisco, Owyang King (歐陽庚). Owyang, a law graduate of Yale University in 1881, commanded exceptional prestige among both Chinese- and European-Americans. Lew Kay, then a 19 year-old sophomore at the University of Washington, gave another speech. He was followed by Bow Wing Moy, the 27-year old son of Moy Bock Him (梅伯顯) of Portland, Oregon. Both young men spoke good, unaccented American English. They clearly were being presented at the banquet to show the Prince (and the upper-class white attendees) that Chinese-Americans had come a long way. Another speech was given in Chinese by Chin Chow Too (陈秋涛), the president of the CCBA.

No records shows that Moy Bock Him was present at the banquet. His absence is puzzling to us. Moy Bock Him, a labor contractor in Portland for decades, was about to be appointed as the Honorary Consul for Oregon, an appointment that was based more on connections and donations than official qualifications. Not dining with the Prince that evening could have meant that he was at odds with the Seattle CCBA. But the relationship could not have been that bad, as the CCBA had invited his son to be a speaker at the prince's banquet.

Goon Dip 阮洽, a business partner of Moy Bock Him, was among the 20 Portland Chinese who came to the banquet but was not chosen to make a speech. Goon was to become the Honorary Consul for Washington, Idaho, and Alaska in 1909. Although already a frequent visitor to Seattle and on friendly terms with the white elite, he may still have been regarded as an outsider by that city’s Chinese community. A third absentee was Chin Gee Hee (陳宜禧), the region’s largest labor contractor and the richest Chinese in Seattle. He was in China at the time of the Prince’s visit.

The Seattle Chamber of Commerce's receipt to Quong Tuck Co. (on behalf of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association -- the CCBA or Chung Wa), after the Commissioners' visit in 1906

Lew King 刘乾

Later in the day, the commissioners visited Seattle High School, then the only one in the city. 2000 students were in the Assembly Hall to see the visitors, who saw many Chinese and American flags as well as laboratories, manual training rooms, etc. The Prince was greatly interested in the fact that young women were allowed to attend public schools. Three Chinese students currently enrolled at Seattle H.S. The commissioners met all of them.

Lunch was at the Rainier Club, still in 2008 the city's leading businessmen's club, after which the party was taken to see the Stetson-Post lumber mill and various other industries. The Prince stayed in his rooms that evening, leaving the other two commissioners, Shang Chi Hong and Li Shengte, free to attend the above-mentioned meeting of the Baohuanghui at the First Presbyterian Church.

The Prince and most of his party left the next day for Minneapolis and Chicago on a special Great Northern train. They were accompanied by A. W. Bash of Port Townsend, Vice-Consul Owyang from San Francisco, and one Miss Chu, also a student at UW. Owyang and Chu may have been taken along because they spoke Mandarin, a rare accomplishment among U.S.-based Chinese of that period, who spoke mainly Taishanese and standard Cantonese. Half of the Prince’s party is said to have spoken Cantonese, which meant they could converse freely with local Chinese Americans. A few must have spoken English as well. But the Prince himself could not communicate in either language, which must have made the company of Owyang and Chu especially useful.

Note 1: Both photos are from Washington State Magazine, 1906 (Apr), p 64-7. The second photo. of the three commissioners, is much better than contemporary newspaper images. The prince's vest shows three of the nine dragon roundels that only the children, siblings, and wives of emperors were entitled to wear.

Joking about the Murder of Chinese at Deception Pass

One of the most horrifying legends about whites killing Chinese in the Pacific Northwest involves legendary smuggler Benjamin Ure of Whidby Island. Ure, a Scot, was a rich man, a leading citizen, a famously successful smuggler, and the subject of many legends about his run-ins with the Revenue Service. Some of the legends are amusing, but the best-known one is not. A typical version appears on Wikipedia:

"In the waters of Deception Pass, just east of the present-day Deception Pass Bridge is a small island known as Ben Ure Island. The island became infamous for its activity of smuggling illegal Chinese immigrants for local labor. Ure and his partner Lawrence "Pirate" Kelly were quite profitable at their smuggling business and played hide-and-seek with the United States Customs Department for years. Ure's own operation at Deception Pass in the late 1880's consisted of Ure and his Native-American wife. Local tradition has it that his wife would camp on the nearby Strawberry Island (which was visible from the open sea) and signal him with a fire on the island's summit to alert him to whether or not it was safe to bring his illegal cargo ashore. For transport, Ure would tie the illegal immigrants up in burlap bags so that if customs agents were to approach then he could easily toss the bags overboard. The tidal currents would carry the discarded immigrant's bodies to San Juan Island to the north and west of the pass and many ended up in what became known as Dead Man's Bay." (Wikipedia, "Deception Pass")

We do not know whether this often-told story is true. Tales about smugglers drowning their human cargo are part of the folklore of many regions. What we don't like is the jocular tone with which this particular legend tends to be told, by Wikipedia and other narrators. For instance,

"Have you ever wondered what it would be like to be smuggled into the US in a burlap bag? In the early 1900's there were plenty of people who got to have that experience courtesy of Ben Ure. Find out what he did with his cargo when he was outrunning the law on your Deception Pass Tour aboard the Island Whaler." [http://www.deceptionpasstours.com/deception_pass_tour_info.php. {Note that the date given on the deceptionpasstours website is incorrect. Ure was already 70 years old in 1900 -- Sandusky (OH) Daily Register 1890-02-25, p2} ]

If the story is indeed true, Ure was a monster, not a likeable rascal. Every Washingtonian would agree if he had routinely drowned innocent Caucasians instead of Chinese. We think that Wikipedia, the local tourism authorities, the Washington State Park Service at Deception Pass, and other interested parties should begin treating Ure and his Native American wife that way, not as Robin Hoods but as vicious, cold-blooded, near-demented murderers. They should relate this part of Washington's past with heartfelt shame instead of tolerant chuckles.

Deception Pass from the east; Strawberry Island is on the right.

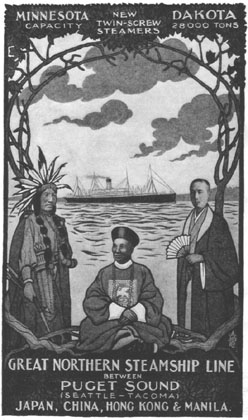

The Prince and his fellow commissioners arrived on a ship that was then one of the two largest and most luxurious passenger liners on Pacific routes. Like her near-identical twin, the SS Minnesota, the SS Dakota had a capacity of 20,700 tons and could carry not only 200 first class and 1800 steerage passengers but also quantities of freight. It was to have a tragically short life, entering service in Seattle in June 1905 and sinking near Tokyo on March 5, 1907.

Both the Minnesota and Dakota had been built for the Great Northern Railroad, to assure traffic for its newly completed rail route from Seattle eastward along the northern edge of the contiguous United States. James J. Hill, the founder-owner of the Great Northern, had made extensive use of Chinese labor in building his railroad. Moreover, his ships were in competition with the Japanese Mail Steamship Company, the NYK Line, for freight and passenger service between Seattle and Asia. Both facts may explain why Hill chose to hire Chinese to man his ships.

According to Tate, the Minnesota before its maiden voyage across the Pacific in late 1904 stopped first in Victoria BC to pick up 172 Chinese crew members: firemen, stokers, waiters, etc. These joined 175 white crew members, who included all the ship’s officers. We may presume that the proportion of Chinese in the crew increased after the ship reached its destinations on the other side of the Pacific -- Tokyo, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Manila -- where the supply of experienced Chinese seamen was greater.

The Dakota too must have had many Chinese working below decks in the engine rooms, kitchens, passenger cabins, and dining salons. While the Prince may have been reassured to see so many Chinese faces aboard, few would have understood the Prince’s Mandarin. One hopes that language barriers between the Cantonese-speaking crew of the Dakota and its English-speaking officers did not contribute to its sad fate on the rocks near Tokyo.

E. Mowbray Tate, Transpacific Steam, 1976, p 120; photo courtesy of Dan Kerlee, www.aype.com

The Chinese crew of the Great Northern's super-ship

The SS Dakota, a Native American, a Chinese official, and a Japanese monk in a Great Northern ad, Harper's Magazine, 1906

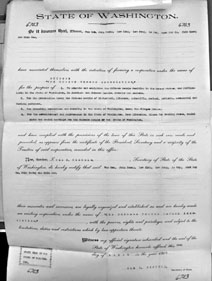

1903 The Seattle chapter of the Chinese Empire Reform Association is incorporated 舍路保皇会注册文件

For information about the Seattle chapter of the Empire Reform Association or Baohuanghui, click here

The commissioners arriving in Port Townsend. The ship is at the left and the welcoming arch in the center,. The commissioners may be glimpsed walking in front of several police guards and top-hatted Seattle dignitaries. (for image data see Note 1 below)

The first Chinese in (or very near) Washington State 第一个到华州的华人

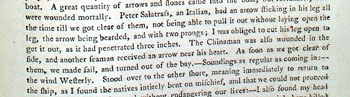

Captain John Meares (see above), uneasy at not having even tried to enter the Strait of Juan de Fuca while sailing from Nootka Sound down the Washington and Oregon coasts as far as Tillamook Bay, decided to send one Mr. Duffin in a sail-equipped longboat to take a look. Duffin would have had 10-12 men (the normal size of a longboat crew) with him, including at least one Italian and a single "Chinaman."

The mini-expedition reached the coast of Vancouver Island near Barkley Sound and proceeded southeastward. Almost immediately it ran into trouble. At Clo-oose (or Claoose) Inlet the local Indians, perhaps offended by the actions of other fur traders, attacked the boat. A shower of arrows wounded Duffin himself, the Italian (quite gravely), and the Chinaman. Escaping by having two men row out of the inlet while the others kept shooting, the boat headed for the "other shore," sailing on a west wind to a location northeast of Tatoosh Island.

The question is, where was this location? John Robson's guess, included on the website, "Sea Otter Fur Traders on the Northwest Coast of North America" <http://pages.quicksilver.net.nz/jcr/~vfur1.html> puts it back at Barkley Sound. But Barkley Sound is northwest, not northeast, of Tatoosh Island, almost due west of Clo-oose, and not in any obvious sense on the "other side." It is more logical to conclude that the west wind forced the longboat to tack over to what is now the American side of the Strait, probably somewhere between Neah Bay and Cape Flattery, before heading northwest to rejoin Meares.

Did the boat actually land on the American side? Duffin does not say, but he and his Chinese crew member (who does not seem to have been seriously wounded) would have had to come very close to the shore anyway. Meares had other Chinese sailors aboard, and during his southward voyage they may well have seen and even landed at such spots as Gray's Harbor and Tillamook Bay in the northwestern U.S.. The same must have been true of Chinese-Filipino crew members in the many Spanish galleons that already for two centuries had been sailing from Manila, heading for Acapulco in Mexico but reaching this continent as far north as California or even Oregon. However, we have no proof of any of this. The first documented Chinese known to have reached any part of the northwestern U.S. was Duffin's anonymous crew member, on July 17, 1788.

The relevant passage from the original 1790 edition of Meares' Voyages. Click here for full page

27 named Chinese seized by the Spanish on Vancouver Island in 1789 (Comment by Bruce M. Watson) 西班牙软禁27个船上华工

Among the gems of information in Martinez's report was a list of the Chinese craftsmen and sailors who had been captured on Colnett's ship, the Argonaut. Watson has already published the list in an article in the Canadian magazine ricepaper (Note 1). The rest of this article is quoted not from the article, which we do not have permission to do, but from notes provided by Watson to the editors:

"The following Chinese cannot be separated individually because of the lack of information in the records and even the incompleteness of the spelling of their names. What is given here is from a copy of Martinez's 1789 report which found its way into the Seville Archives. This group was the second group of Chinese that came out [to North America], this time in the Argonaut (James Colnett) under John Meares, the first group of 49 coming out on the Felice and Iphigenia in 1788. This second group comprised 7 carpenters, 5 blacksmiths, 5 bricklayers and masons, 4 tailors, 4 shoemakers, 3 seamen and 1 cook. They appear to have come willingly on board but Colnett commented "I had some difficulty in getting the Chinamen on board, being Obliged to smuggle them from the shore to prevent the imposition of the Mandarins." [The imposition probably involved some payment to senior officials].

"When they reached Friendly Cove [on Vancouver Island], the Argonaut, and all aboard, were seized by Martinez and the Spanish. While almost everyone else was sent south, most of the Chinese were held back to assist Martínez in completing Spanish buildings before leaving on October 21, 1789 on the Princesa and San Carlos as prisoners to San Blas [in Mexico]. Many months later, six of the below Chinese deserted on July 11, 1790, just before Colnett was given back his vessel, and their fate is unknown. Those six have not been identified. The remainder appear to have crowded onto the Argonaut and sailed back to Nootka. They spent from October 1790 to March 1791 trading for furs before sailing to China. The vessel would have taken them to Macao where they probably disembarked in 1791.

[Names from Martínez's report] 华工名字

"Sinfo

Acchan

Acchan

Tong

Tong

T.. ...o

Accah

Accah

T'...ou

T'...ou

Allon

T.. ou

T.. ou

Caphou

Caphou

Te.. en

Asseu

Asseu

Annam

Annam

Attou

Uppo'vah

Uppo'vah

Achee

Achee

Ah He

Assam

Assam

Artoyah

Artoyah

Amusayah

Acch'ou

Acch'ou

T'...ou

T'...ou

Ammey

Attahac

Attahac

Ahoy...ha

T'ou

T'ou

Acchog

Assan

Assan

Acchang

Accong"

Accong"

Watson deserves praise for having thought to try the Archivos de las Indias. It is marvelous to have so many names of individual Chinese in our region at such an early date. As suggested previously, names with the Ah prefix, especially of individuals hired in Macao, are likely to be Cantonese. Making allowances for Spanish-English vagaries in hearing and writing Asian words, almost all of these names are perfectly possible in Chinese. The one exception is the four-syllable Amusayah. Could it conceivably be Malay?

Note 1: Bruce McIntyre Watson, "Pacific Interconnectedness, The Story of Chinese Craftsmen and a Mexican Connection." ricepaper, 2007 (vol 12, no 3), pp 60-62

Bruce Watson, a Vancouver B.C. historian, has compiled extensive notes on Chinese in the Pacific Northwest. Several years ago, acting on a hint that there might be relevant data in early Spanish records, he consulted a new source on that subject: the Archivo de las Indias in Seville, Spain. Sure enough, he found a report written by the Spanish naval officer Esteban José Martínez, who in 1789 had seized the ships of John Meares, one of them captained by James Colnett, at Nootka Sound so as to show the world that Spain, not Britain, had legitimate control of the Northwest Coast (for the resulting "Nootka Crisis," see the relevant Wikipedia article).

Martínez,(Wikipedia image)

Meares (Wikipedia image)

Journal of the Indian Archipelago & Eastern Asia, 1855: 450). Curiously, the modern city-state of Singapore, which has a mainly Chinese population, still has a Chinatown that is called such by Singaporeans.

The English name of Singapore's Chinatown may have been a word-for-word translation of the Malay name for that settlement, which in those days was probably “Kampong China” or possibly “Kota Cina or “Kampung Tionghua/ Chunghwa.” We cannot find any Chinese-language term that could be literally translated as “Chinatown.” American and other Chinese gave Chinese quarters of non-Chinese cities such names as “Tang Ren Jie” (Tang [dynasty] People's Street) and never, until very rcently, “Zhongguo Cheng” (China Town).

The first appearance of “Chinatown” outside Southeast Asia may be in 1852, in a book by the Rev. Edwin F. Hatfield, St. Helena and the Cape of Good Hope (1852:197), who applied the term to the Chinese part of the main settlement on the remote South Atlantic island of St. Helena. The island was a regular way-station on the voyage to Europe and North America from Indian Ocean ports, including Singapore.

The first American usage we can find dates to 1855. when the San Francisco newspaper Alta California (1855-12-12: 1) described a “pitched battle on the streets of [SF's] Chinatown.” Other Alta articles (1857-12-12: 1; 1858-06-04) from the late 1850s make it clear that areas called Chinatowns existed at that time in several other California cities, including Oroville and San Andres.

The term seems not have been used much outside California until 1859, when it appears as the name of a mining camp in Carson County, Nevada. Both the New York Times (1859-07-07:) and the Placerville (CA) Mountain Democrat (1859-06-11) imply that this Nevada Chinatown was a separate settlement rather than a Chinese area in a larger settlement. As the 1860 census noted, Carson County's Chinatown was then inhabited mainly by whites (Kennedy 1864: 564).

By 1869, “Chinatown” had acquired its full modern meaning all over the U.S.. For instance, the Defiance (OH) Democrat (1869-06-12: 5) wrote: “From San Diego to Sitka..., every town and hamlet has its 'Chinatown'--its poorest, meanest, and filthiest.” In the same year the New York Herald (1869-11-13: 6) quoted the San Francisco Bulletin in describing a wedding that took place in San Francisco's “Chinatown.” After 1870, the term began to be used frequently in many North American newspapers, books, and magazines. But not all Chinese quarters of American cities were called Chinatowns at such an early date. In Chicago, for instance, the Clark Street Chinatown does not seem to have been called by that name until the 20th century (www.ccamuseum.org/Research.html#anchor_40)."

In British publications before the 1890s, “Chinatown” appeared mainly in connection with California. At first, Australian and New Zealand journalists also regarded Chinatowns as a Californian phenomenon. However, they began using the term to denote local Chinese communities as early as 1861 in Australia (Ballarat Star 1861-02-16: 2) and 1873 in New Zealand (Tuapeka Times 1873-02-06: 4)

1844: The First "Chinatown"

When one thinks about it, the term "Chinatown" is puzzling. Most other ethnic enclaves in American cities were or are known by a term derived from a national adjective-plus-”town” as in Frenchtown, Greektown, Germantown, etc. So how did the national noun-plus-”town” form come into being, to be applied first to Chinese enclaves and later by analogy to other East Asian enclaves, as in Japantown and Koreatown?

As far as we know, the term was first used in Asia. One of its earliest appearances was in 1844 in the form of “China Town,” referring to the Chinese quarter of Singapore (Simmond's Colonial Magazine and Foreign Miscellany, 1844, Jan-Apr: 335; Sydney Morning Herald 1844-07- 23, p 2; see also

Singapore's Chinatown, from Wikicommons

1844. Modern view of

Singapore's Chinatown

(UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED ALL DATA ON THIS PAGE COMES FROM THE EDITORS' OWN RESEARCH ON PRIMARY SOURCES & ARTIFACTS)

New Discovery! The First Chinese to Visit and Write About the Pacific Northwest 最早登陆及记载阿拉斯加的华人- 谢清高

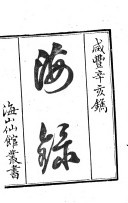

The book titled Hai-lu 海录 [Sea Records] describes the travels of a professional sailor named Xie Qinggao 谢清高, as recorded and edited by Yang Bingnan 杨炳南, a junior scholar from Xie’s home district, Meixian 梅县. Published in 1820, the book reflects Xie’s memory of the many foreign countries he visited during the 14 years he worked as a sailor on Portuguese and perhaps other European ships, from about 1782 to 1796. He settled in Macao 澳门 after retiring from sea faring. That was where he met Yang. Intrigued by Xie’s experiences and fine memory, Yang took responsibility for writing down the text, organizing it in logical parts, and perhaps editing it to mesh with what Macao Chinese knew of the outside world in the early 1800s.

The book is deservedly famous. However, it has gotten attention mostly for the details it provides on Southeast Asia and Europe. A last section, describing a place called Kai-yu 開於, has generally been passed over or even omitted in some later editions. The few scholars who have tried to identify Kai-yu have placed it in the Kuril Islands, north of Japan. We disagree. We think Kai-yu was almost certainly in Alaska or northern British Columbia, somewhere between Prince William Sound and Haida Gwaii, the Queen Charlotte Islands.

“Kai-yu is located in the Northeast Sea. Sailing north from Wafu [Hawaii], one reaches there in about 3 months. Xie Qing-gao states: In the past I followed a foreign [Portuguese] ship there to buy furs and skins of sea otters, "gray rats" [i.e., mustelids--fishers, martens, minks, etc.], and foxes.

The temperature was freezing cold with snow all over the ground. When the ship reached the entrance to the harbor there were icebergs floating out. Large ones could be several feet wide. Not daring to go further, [the ship people] fired a canon. Then came the native people rowing small canoes to lead the way. Some ship people could speak their language hence enabling transactions. I heard the name of the place pronounced somewhat like “kai-yu”, so I call it Kai-yu.

The native people who lived there were not so many. They looked much like Chinese. They ate dried fish.

Every day the Sun could be seen in the south, but only several tens of degrees above the horizon. It set between one and two o’clock in the afternoon but it didn’t become too dark until nine or ten o’clock. In between it was bright enough to see people. The moon could be seen during the full-moon periods but no stars were visible.

When I first arrived my hands and feet suffered from frost bite. But not the natives. They all held two large wooden sheets in their hands. When seated, they put their feet on those sheets. I sensed that there must be a reason so I copied them. Recovery was the result! I have no idea what kind of wood that was.

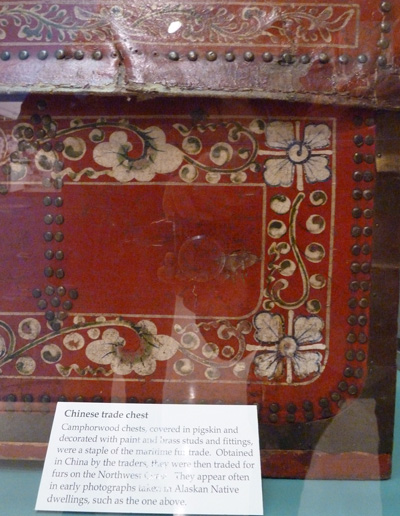

The natives love Chinese leather chests and trade fur for them. I once went ashore and entered a native home. Nobody was in it. I saw more than 10 leather chests. I left in horror after opening some chests to find human heads inside.

From there we sailed north for another some 20 days, reaching another harbor. A cannon was fired but no one came. Hence none dared to make further progress. We heard that north of it was the Ice Sea. …”

1) Kai-yu is said to be north of Hawaii, like Alaska and unlike the Kurils, which lie far to the west-northwest.

2) There is no floating ice in the Kurils, which are too far south and kept warm by the Japan Current. By contrast, icebergs and ice fields from melting glaciers are present in many southern Alaskan inlets until mid-summer.

3) The native Ainu of the Kurils were never said to be headhunters. But the Tlingit, Haida and Kwakiutl of southern Alaska and northern British Columbia did hunt heads. One of the best known of all ethnographic films, directed by the great Edward Curtis, is set among those Indians. Endorsed by Indians and non-Indians alike, its title is In the Land of the Headhunters.

4) Northwest Coast Indians routinely used Chinese chests for storage. They bought these from white traders seeking sea otter and other furs.

5) The Kurils, between 45° and 50° north latitude (that is, well south of London), have day lengths between 7.9 and 8.4 hours at the winter solstice. The town of Sitka in southern Alaska, at 58° north, has 6.5 hours of daylight on that day. Prince William Sound, at 61° north in the upper Gulf of Alaska, has a mid-winter day length of 5.5 hours.

6) As shown below, some fur-trading ships from Macao reached as far as Kodiak and Unalaska Islands. It was there that natives and foreign traders would have known about the frozen Arctic Sea north of Bering Strait.

7) "Kai-yu" could well be the name of a place on North America's northwestern coast. "Gwaii," for instance, is a Haida Indian word meaning "island."

Where was Kai-yu? 開於- 北美洲? 亚洲? Xie’s description points unmistakably to Alaska or northern British Columbia rather than the Kurils:

Yes, and with Chinese on board. Xie Qinggao was probably already a seaman of some kind when he was rescued from a shipwreck by a European ship in Southeast Asian waters. His subsequent fourteen years on European vessels gave him enough language skill to later become an interpreter in the Portuguese "colony" of Macao near Canton. His Portuguese orientation is shown by his consistent use of Xiyang 西洋 ["West Ocean"] to mean Portugal specifically, even though others used the same term to mean Europe in general.

And there were plenty of available ships. Due to a short-lived fad for imported sea otter furs among wealthy Chinese, more ships sailed from Macao to the Northwest Coast in the 1780s and 1790s than at any other time before or since.Moreover, most such ships, like almost all other Western ships sailing from southern China in the eighteenth century, would have had at least some Chinese crewmen aboard. This was because in those days the long voyage from Europe to China meant that each ship was bound to lose crewmen from accidents and scurvy, and that there were few unemployed European sailors at Chinese ports to fill those job vacancies. Hence, local Chinese sailors were routinely hired by foreign ship captains. Long-distance Western ships in the 17th-19th centuries tended to have international crews anyway, often including Indian Lascars, Malays, Filipinos, Native Americans, Polynesians, and/or West Africans. These were rarely mentioned. That a few Chinese had been added to a crew roster would not ordinarily have seemed worth including by those who recorded such voyages.

Did Ships Sail from Macao and Canton to the Northwest Coast of America in the 1780s or 1790s? 谢清高是跟葡萄牙船到北美洲?

We have used the 1981 edition published by Hunan People's Publishing, titled Cheng-cha bi-ji (wai yizhong). "乘槎笔记(外一种)”. 湖南人民出版社.

This edition of Xie's "Sea Records" is based on versions published in 1851 and 1877. The translation below comes from pages 44-45. The image on the left is the title page of the collection that contains the1851 edition. Text in brackets or in boldface are our own additions.

Examples of the 18th-19th century Chinese chests favored by Native Americans in Alaska. They are made of mold- and insect-resistant camphor wood covered with pigskin leather and floral paintings. Photographs taken at Ketchikan's Tongass Historical Museum, 2013

Argonaut and Princess Royal, captain: James Colnett and owned by John Meares. In 1789, the Argonaut and its crew, including 29 Chinese (3 sailors, 25 craftsmen, and one cook), were seized by the Spanish government under Martinez just as they reached Nootka Sound from Macao. This incident caused a major dispute between Great Britain and Spain (Nokes, passim; Pethick, passim).

Felice Adventurer and Iphigenia Nubiana. Their first voyage, under the Englishman John Meares, but flying a Portuguese flag, took place in 1788. Sailing from Macao, they reached Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island with 49 Chinese aboard, mostly craftsmen but a few sailors too (click here for CINARC data). In later years, the same ships, still owned by Meares but without him on board, voyaged repeatedly from Macao to the Northwest Coast, perhaps with Filipino, Lascar [Asian Indian, and Hawaiian as well as Chinese crew members (Nokes, p 175). In 1791, 1792, and 1793, the ships were under the overall command of a Portuguese captain, Francisco Viana (Pethick p 132-3).

Florinda (captain: William Coles or Thomas Cole), 1892. Left Chinese waters in March 1792, possibly in Batavia (Jakarta) before that (Pethick, p 133)

Grace (captain: Joseph Ingraham) and Hope (captain R. D. Coolidge). Wintered at Lark's Bay near Macao and Guangzhou, then sailed to Haida Gwaii, the Queen Charlottes, on the Northwest Coast. The Hope went on to Nootka where it met the Daedalus and visited the newly built Spanish fort (Pethick, p 118-121)

Whether Qinggao (pronounced "Chinggow" in Mandarin and "Chinggoe" in Cantonese) came to North America on one of these or on another ship will probably never be known. There is almost no chance that he can be securely identified from European maritime records. But it is tantalizing to note that one of the three named Chinese on board the Phoenix, which visited Alaska and British Columbia in 1792, was shown on the ship's crew list as "Chinkqui." As noted above, the other two were named Angee and Highee.

Phoenix, 1792 (captain: Hugh Moore). Sailing from India and mainly crewed by Lascar (Asian Indian) and Hawaiian seamen, the Phoenix may have touched at Macao on the way to the northern Pacific. Moore and his ship spent several weeks at Russian trading posts in far northern latitudes, on Kodiak Island and Prince William Sound

(Pethick, p 131-2)

St. Joseph and Fenis [São Jao y Fenix], captained ostensibly by a Macao Portuguese, John de Barros Andrade, but in actuality by a British employee of John Meares, Robert Duffin. Sailing from Macao, the ship spent the summer of 1792 in the Haida Gwaii (Queen Charlotte Islands) before reaching Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island (Wikipedia, “Fenis and St. Joseph” article)

John Bartlett, “A Narrative of Events in the Years 1790-1793,” in The Sea, the Ship, and the Sailor. Salem: Marine Research Society, 1925.

John Meares, Voyages Made in the Years 1788 and 1789 from China to the North West Coast of America. London, 1790

J Richard Nokes, Almost a Hero: The Voyages of John Meares, R.N., to China, Hawaii and the Northwest Coast. Washington State University Press, 1998.

Derek Pethick, The Nootka Connection: Europe and the Northwest Coast 1790-1795. Vancouver, 1980.

Bruce McIntyre Watson, "Pacific Interconnectedness, The Story of Chinese Craftsmen and a Mexican Connection." ricepaper, 2007 (vol 12, no 3), pp 60-62. Also, unpublished personal information.

Wikipedia, “List_of_historical_ships_in_British_Columbia” article

The Mercury/ Gustavus III on the Northwest Coast, from John Bartlett's Narrative, 1790-93. The ship had three Chinese crew members at the time this sketch was made,

Xie might have been aboard any of those ships. While some actually flew Portuguese flags, the national status of others were kept obscure for legal reasons. Chinese sailors might have believed that any Western ship repaired, provisioned, and crewed in Macao was essentially Portuguese.

Ships on which Xie could have reached North America's northwest coast included:

Jackall (captain: Alexander Stewart), and Prince Lee Boo, (captain: Gordon), 1894. Both ships spent the winter of 1893 in Macao (Pethick, p 166)

Margaret (captain: James Magee). Wintered in Macao in 1792-3, on the Northwest Coast again the following summer (Pethick, p 173).

Mercury [or Gustavus III], owned by the Macao-based English trader John Henry Cox. The ship had visited Unalaska Island in the Aleutians briefly in October, 1879 (Wikipedia, John Henry Cox entry), and returned to the Northwest Coast in the spring and summer of 1791, sailing from Guangzhou and Macao with three Chinese crewmen (named Angee, Highee, and Chinkqui) along with one Goanese, one Hawaiian and one Filipino. (Watson, personal information; Bartlett in Marine Research Society 1925: p 294).

Captain George Vancover's supply ship Daedalus and the Spanish fort at Nootka Sound, 1792. Click for enlargement and photo credit

Thirteen foreign ships gathered in Nootka in the summer of 1792. Two belonged to the Spanish government (under Bodega y Quadra) and two to the British government (under George Vancouver). The other nine ships, all private, were British, American, and Portuguese. Three of the nine--the Felice, Hope, and Margaret--had wintered in Macao and may well have had at least a few Chinese crewmen on board

1792. The ship Gustavus III at Vancouver Island, with 3 Chinese on board,

This page was last updated: August 30, 2018

The Fusang Question: Was this mysterious ancient kingdom (AD 599) located in the Pacific Northwest? Did early Chinese travelers visit it?

No and no. The idea that the semi-legendary kingdom of Fusang was discovered by a Chinese monk named Hui Shen in AD 599 was first popularized in the West by a French nobleman, Joseph de Guignes, in 1761 and has been repeatedly mentioned by enthusiasts, including Chinese and European North Americans, ever since (Note 1). A decisive shortcoming of the Fusang hypothesis was pointed out by the German orientalist Julius Klaproth in 1831: DeGuignes, whose Chinese was not very good, misunderstood the relevant historical text. It does not say that Hui Shen was a Chinese explorer who went to Fusang but, instead, a Fusang native who came to China (Note 2). A look at the text, preserved in the Liang Shu (the History of the Liang Dynasty) [for the original Chinese version and an English translation, click here], shows that Klaproth was right. Hui Shen was said to be from Fusang, not China, and the homeland he descibed, with horses and wheeled carts pulled by horses, oxen, and deer, does not seem at all like preColumbian America.

The notion that Hui Shen was actually Chinese and that he traveled from China to Fusang has goten a filip lately because of a translation offered by Lily Chow in her otherwise excellent Chasing their Dreams (Note 3), in which she quotes the original text to the effect that Hui Shen was one of a group of five Chinese monks who had gone to Fusang forty years previously in 558 before returning alone to China in 599. However, that is not what the text says [click here]. The monks in question are clearly stated to be not from China but from Jibin 罽宾 or Gandhara, in modern Pakistan and Afghanistan, which in those days was an important center of Buddhist learning. Moreover, Hui Shen is not mentioned as one of them.

In any case, if Hui Shen was not Chinese and did not travel from China to Fusang, then we need not search too hard for the actual location of the Fusang of the Liang Shu. It might have been in Japan or the Northeast Asian mainland, as most researchers believe. It might have been a product of Hui Shen's imagination. But we may be sure of one thing. There is no proof or even a hint that any Chinese traveler of that period ever went to Fusang. Hence, the Hui Shen story is not relevant to the widespread (and in our opinion, quite plausible) belief that Chinese may have discovered America long before Lief Ericson and Columbus.

Note 1 Stan Steiner,1979, Fusang, The Chinese Who Built America.

Note 2 Joseph de Guignes, 1761, Recherches sur les Navigations des Chinois du Cote de l'Amerique, et sur quelques Peuples situés a l'extremité orientale de l’Asie; Julius von Klaproth, 1831, “An Inquiry into the Country of Foo-Sang, Mentioned in Chinese Books,” Asiatic Journal, vol 5: pp 298-303;

Note 3 Lily Chow, 2001, Chasing their Dreams: Chinese Settlement in th Northwest Region of British Columbia. Her translation is quoted extensively by Wikipedia in http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fusang