RESEARCH TOPICS 研究课题

When was the last time you ate

chop suey?

What is it anyway?

Meat, celery, bean sprouts, etc.

Origin myth #1: Invented for Li Hung Chang's visit to New York in 1896

Origin myth #2: Invented by Lem Sem of San Francisco in 1893

Origin myth #3: Invented in Calif-ornia mining camps in the 1850s.

All are wrong. Copy suey is first mentioned in 1884 by Wong Chin Foo, in New York

IV. The Boston Theory: that it was invented there in 1879 at the Hong-Far-Low restau-rant. But Hong-Far-Low did not exist until about 1905. The chop suey claim on its menu dates to the 1910s or later.

Origin myth #4: Invented in a Boston restaurant in 1879

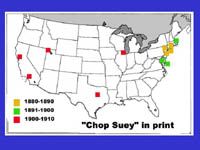

There is no evidence that it was known in the West before 1900

The Origin of Chop Suey 杂碎餐的由来

Chop suey is definitely Eastern

The Rise of the Chop Suey Restaurant in the U.S. 美国 杂碎餐馆的兴起

| ||||

Why chop suey made a difference

in most of North America

Its appearance marked a turning point in American Chinese history

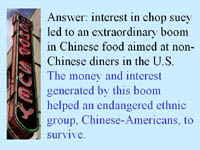

The chop suey fad caused a boom in Chinese restaurants for non-Chinese

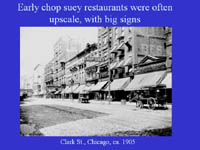

They proliferated and got big

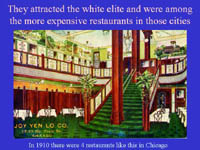

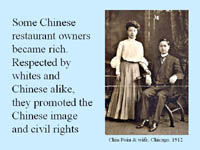

They also moved up-market, and their owners got rich

Some owners were accepted by the European-American upper classes

And for the first time, whites began to appreciate a part of Chinese culture

And not just whites either

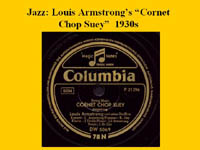

For instance, Cornet Chop Suey by Louis Armstrong 'und seine hot five'

But the situation may have been different in the Northwest

Chinese Restaurants and Chop Suey in the Pacific Northwest 西北角早期杂碎餐馆

An Early Chinese Herbal Doctor in John Day, Oregon

On July 6 2008 the Seattle Times (page B1) ran a long feature article by Richard Cockle, "Chinese doctor's Old West cures will stay lost without translation." Cockle's subject was the 1500 herbal remedies included in the 20,000 pages of papers left by Ing "Doc" Hay, a Chinese herbal medicine doctor who practiced in John Day, Oregon, from the late 1890s through the late 1920s. Like a number of other Chinese herbalists in remote parts of North America, Ing Hay became an important provider of medical services to European-Americans as well as Chinese. By 1920, according to curator Christine Sweet of the Kam Wah Chung Museum in John Day, most of his patients were white and - remarkably - more than half were white women. Apparently, many Oregonians (and, according to Sweet, Idahoan, Washingtonian, and northern Californian patients as well) were not so prejudiced against Chinese that they rejected Chinese individuals and culture when their own lives were at stake.

The Seattle Times article cites Linda Barnes, a researcher at Boston University School of Medicine, as saying that for so many early herbal remedies to have been preserved in written form is of special importance : "It is almost as if he just left. We can see what herbs he was using. We can see his prescriptions. We can see the letters from his patients." But the problem, according to Sweet, is that everything Doc Hay himself wrote is in Chinese. This makes it hard to evaluate his remedies even though they might be useful in modern medicine. The Kam Wah Chung Museum has applied for a grant to help with translations. "A cure for cancer might be too much to hope for," said Sweet, "but perhaps not. People say he was able to cure about anything."

The editors of CINARC are not too hopeful about that. The possible uses of traditional herbal remedies in modern medicine have been a major area of study in China for several decades now, and the discovery of new miracle drugs in the Chinese herbal pharmacopoeia - for instance, artemisinin for malaria - may now be coming to an end. However, Doc Hay was clearly an intelligent traditional pharmacist working in an area with many plants that were new to Chinese science. Who knows what he might have discovered?

Early Herbal Remedies for Contract Laborers in Seattle

西雅图早期华侨陈宜禧商业档案中的医方

Medicines in Chin Gee Hee’s Chinese-language account book

As a contribution to the study of Chinese herbal medicine in the Northwest during the late 19th century, we are including a translation of simple remedies supplied to workers, most of them in working for canneries, railroads, farms, and lumber mills, in the 1880s and 1890s. The remedies are included in the papers of Chin Gee Hee, a Seattle labor contractor and store owner, that are currently preserved among the Willard Jue Papers at the University of Washington. He seems to have meant them for use by workers whom he was supplying on contract to employers in Washington, Oregon, British Columbia, and perhaps Alaska. Such contractors were responsible for the health of their workers as well as their food and lodging.

Chin's English was quite good, so his prescriptions were in a mixture of English for American ingredients like sarsaparilla and Chinese for such ingredients as balloon flower and angelica root. We identified the Chinese drugs by using Colored Illustrations of Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs (edited by Xu Guojun. Fuzhou, 1990).

Prescriptions

a. Undated. Blood in saliva.

b. Undated. Swollen feet.

c. Dated 1901. Shingles (“Running Snake”).

d. Undated. Mouth sores.

e. Undated. Belly button wind [or belly button ache?].

f. Undated. Headache.

g. Undated, Toothache.

h. Undated. Chest pain.

[coptis root]…. Grind them fine for tea."

Kam Wah Chung Museum,

John Day,Oregon

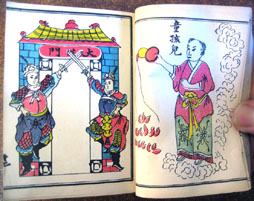

Chin Gee Hee's diagram of the 13 massage points for curing belly button wind. The points are shown by circles.

| ||||

Ralph investigates immigrant smuggling on the U.S.-Canada Border, 1890

In 1890 Julian Ralph was assigned by Harper's Monthly to investigate the smuggling of Chinese into the US. After traveling to Canada and interviewing a large number of experts and participants, he concluded that several thousand illicit Chinese immigrants were entering the country each year.

Most came in from British Columbia to Washington State. An average of 1910 new immigrants arrived in BC from China each year. According to Ralph's Canadian informants, "99 in 100 of these are intending to smuggle themselves over the US border."

Ralph goes on to say that "There is no part [of the US-Canada border from Montana on west] over which a Chinaman may not pass into our country without fear of hindrance; there are scarcely any parts of it where he may not walk boldly across it at high noon. Indeed, the same is measurably the case all along our northern boundary even upon the St. Lawrence north of our State, where smuggling has always been a means of livelihood whenever varying tariffs made it remunerative.

"The lawless practice does go on from one end of the border to the other. Chinamen at work in the forests beside the Columbia steal in by the Kootenay trail; others cross the St. Lawrence, others the plains and prairie, others the Great Lakes. Those who transport the Chinamen are all white men. The resident Chinese act as their confederates and as the agents of the smuggled men, but do no part of the actual smuggling ..."

Ralph notes that there were other ways into the US that did not involve clandestine border crossing. In 1890, an average of 60 Chinese laborers per month were arriving by ship in San Francisco and claiming to be American citizens by birth. All of these had to be allowed to land, in order to permit an investigation of their claim in the federal courts.

A large proportion of these putatively illicit immigrants succeeded. "Less than twenty- five per cent, are sent back to China. The claimants of citizenship may be men who were once before laborers here, and who possess our violated pledges in the form of certificates; some may in reality be born citizens." Ralph estimates that about 1000 immigrants per year were entering the country in this way.

Data from Julian Ralph, The Chinese Leak, Harpers Monthly, 1891, Vol 82: 515-525. Text, originally written by CINARC's editors, reprinted

from website of the Chinese-American Museum of Chicago, http://www.ccamuseum.org

Annals of Northwestern Smuggling: By Land and Sea

This section will continue to grow as we find more articles in contemporary newspapers and magazines. Other sections will deal with other aspects of immigrant smuggling: land routes, official connivance, false documents, and so forth. Latest entry: 6/15/09

1882

{The Chinese Exclusion Act is passed by Congress, making it almost impossible for working-class Chinese legally to enter the United States. The smuggling of illegal immigrants begins almost immediately.}

1883

The English sloop Photographer is charged at Port Townsend with smuggling Chinese into Washington Territory from British Columbia. [New York Times 1883-08-10, p 5]

Reports reach Port Townsend that (1) a boat containing 19 Chinese was seen passing Orcas Island, “headed for Washington Territory;” and that (2) a resident of Whidbey Island saw “six canoes containing some Indians, but mostly Chinamen, try to make a landing Sunday night but that they were frightened away by seeing a man on the beach.” [New York Times 1883-09-02, p 2]

{This is one of the few cases that we have found of Native American rather than European-American boatmen smuggling Chinese into the U.S}.

1884

"Advices from British Columbia state that unless immediate steps are taken to prevent the smuggling of Chinamen into the United States from that province before Spring, nearly the whole Chinese population of British Columbia will be transferred over to Oregon and Washington Territory. Fourteen fishing smacks have been discovered engaged in the trade, realizing handsome profits for their owners. As high as $80 per head for women and $80 [sic] for Chinese men are now paid to Captains of boats for running them across the line. It is stated that the United States customs officers are very negligent in the performance of their duties, as smuggling, which at first was carried on quietly, is now openly going on under their eyes. It is stated that within the past eight weeks over 1,000 Chinamen have passed over voluntarily." [New York Times, 1884-09-28, p1] [NEW 2/15/09]

1884

An article in the Modesto [Washington Territory] Strawbuck claims that thousands of Chinese have been smuggled in from Victoria, British Columbia, since the passage of the Restriction Act in 1882. “Chinese merchants in Portland, Oregon, in Seattle and other Sound ports in Washington Territory, and Victoria, British Columbia, furnish the cash, and white men transact the business. It is a matter of almost nightly occurrence, the weather being very favorable, for one of more small sailing craft to run past Port Townsend freighted with Chinese taken on board at Victoria.” [New York Times 1884-07-07, p 2]

Late 1880s

The notorious Ben Ure and his colleagues are active, smuggling Chinese with the help of Ure's Native American wife. They are accused of drowning their Chinese customers when threatened with search by the Coast Guard's revenue cutters. [See http://www.cinarc.org/History.html#anchor_87]

1885

[Normally tolerant of corruption, the Northwestern public might have reacted negatively to any hint of bribe-taking on Beecher's part. His father, Brooklyn's Henry Ward Beecher, was the most famous American preacher of his day and also, in the 1880s, an outspoken opponent of the Chinese exclusion laws.]

1885

On December 30, the Portland Oregonian relates a “horrible story” told by a recently convicted smuggler. He claims that one day last summer, an Italian boatman left Victoria for the American side of the Straits with seven Chinese on board. When the United States cutter Oliver Wolcott approached in order to inspect his cargo, he “became alarmed … He called the Chinamen out of the cabin one by one, and as each man came on deck the Italian struck him on the head with a club and then pitched him overboard.” [New York Times 1885-12-31, p 1]

{Reading between the lines, the Oregonian is suspicious about the truth of the story. See also Deception Pass }

1885

"Twenty-four Chinese laborers without certificates were abandoned on a rock in the Straits of [Juan de] Fuca by the Master of a schooner who had failed to smuggle them ashore. The marshal was ordered by the Commissioner of the Court to take them back to British Columbia; the British authorities refused to receive them unless the Canadian head-tax of fifty dollars was paid. The Chinese were then confined in a jail on NcNeil's Island; when brought into court again Justice Greene of Seattle ordered the marshal to take them over to British Columbia regardless of Dominion authorities; and the Chinese, supplied with provisions for a few days, were so disposed of." [Mary Roberts Coolidge, Chinese Immigration, 1909, pp 186-7; data from The Oregonian, Dec 5, 1885]

{The preceding murder story may be a fabrication but this one, showing almost equal ruthlessness on the smugglers' part, has the ring of truth}

1885-1886

{Anti-Chinese violence breaks out in several parts of the Northwest. A number of Chinese are murdered. Tacoma expels all its Chinese residents, while Seattle and Vancouver BC try to do the same. Afterward there is a lull of several years in illegal crossings from Canada into Washington.}

1890

“First documented opium seizure -- made by USRC Wolcott on 31 August 1890 … Stationed in the Straits of Juan de Fuca, the cutter conducted a boarding of the American steamer George E. Starr. It found an undeclared quantity of opium and seized it and the vessel.” [http://coastguardnews.com/a-legacy-of-maritime-law-enforcement/2007/12/04/] [But see the Beecher story above, in 1885]

{Note that the crime involved is that of evading customs duties. The sale and use of opium did not become illegal in the United States until 1909. It was banned in British Columbia a year earlier, in 1908. Repackaging of imported opium in Victoria's Fisgard Street Chinatown, mostly for reshipment to the U.S., reached a peak in the early 1890s.} [http://web.uvic.ca/vv/student/chinatown/opium/p3.html]

1890

Four smuggling sloops have been seized near Port Townsend in a six-week period. One of the vessels “was found to be regularly fitted for smuggling Chinese into the States and the [U.S. Customs] Collector has information proving positively that the sloop has been making regular trips, carrying from ten to twenty Chinese over the border every time. Besides arms, on board was an extra outfit of sails, tanned buff color, in order to escape being seen at a distance.”

[Chicago Tribune 1890-07-14, p 1]

1891

The Seattle-based sloop Flora is fined 400 dollars by the customs authorities of Victoria. A newspaper comments that “the large sums paid for successfully landing Chinese laborers tempt not only the Vancouver boatmen but American craft of various sorts and sizes to engage in it.” [New York Times 1891-07-15, p 4]

{Sailing ships seem to have gone out of fashion among smugglers at about this time. The future would belong to steam-powered smuggling craft.}

“Capt. Tozier, commanding the revenue steamer Wolcott, who seized the steamer George W Starr at Victoria B.C., for smuggling Chinamen, has been instructed to deliver the streamer and the Chinese to the Collector of Customs at Port Townsend.” [Chicago Tribune 1891-09-02, p 9]

1892

Some British Columbian smugglers may be bypassing Washington State, as suggested by this newspaper article: "The smuggling schooner Halcyon has returned to the Victoria (B.C.) Harbor as secretly and mysteriously as when she sailed from that place six weeks ago, heavily laden wirh opium and Chinese. Her officers and crew will give no information regarding the cruise, but the United States Secret Service detectives who are in Victoria watching her movements learned through one of he seamen that the vessel had touched on the California Coast and at the Hawaiian Islands since leaving Victoria." [New York Times 1892-10-02]

1893

A nice case from a secondary source: "In December 1893, the U. S. district attorney for Oregon indicted twenty-eight men in the United States District Court. The case turned on events that had occurred two months earlier, in October of the same year, when a 450-pound shipment of opium was loaded aboard the

steamer Wilmington in Victoria, British Columbia. Suspicious of the shipment,

a Victoria customs agent telegraphed ahead to the Astoria, Oregon customs

house, located at the mouth of the Columbia River—the main waterway into the

city of Portland. Working on a tip, the owners of the Wilmington headed downriver

to retrieve the ship and dump its illicit contents. But customs agents had already

apprehended the shipment. Then began one of the largest nineteenth-century

opium and immigrant smuggling cases on the West Coast. Of the Portland-British

Columbia operation, one San Francisco newspaper declared, 'the [smuggling] has

been carried to an extent and audacity little short of marvelous.' "

[Griffith, Sarah M., "Border Crossings: Race, Class, and Smuggling in Pacific Coast Chinese Immigrant Society," Western Historical Quarterly 2008, vol 5, 4: pp 473-492; image from J. G. McCurdy, Pacific Monthly 1910 p 190]

1894

“Port Townsend, Wash,, Feb. 21. – The British steamer Fairy of Victoria was seized near Point Morrowstone today by the revenue cutter Wolcott and eight Chinese aboard captured. Two white smugglers, who had command of the steamer, escaped by rowing ashore in a small boat. Fairy is a speedy craft of ten tons burden and has been engaged in Chinese smuggling for some time. United States customs officers say she landed over 100 Chinese in this vicinity during the last few weeks and is one of the most daring smugglers in the Northwest.” [Chicago Tribune 1894-02-22, p 1]

1895

It is announced that two new revenue cutters are being built in Port Townsend for use by the Coast Guard in Puget Sound. Each will be heavily armed, have a crew of one lieutenant and seven men, and – thanks to a vertical inverted direct-acting compound engine with a high-pressure cylinder of 7 inches and a 42-inch diameter propeller – "will reach a top speed of 15 knots." The main purpose of the ships will be to run down and capture “small steamers engaged in these waters in smuggling into the United States opium and Chinamen.” The opium is said to come from “manufactories” in Victoria, B.C. [New York Times 1895-12-08, p 19]

{The “manufacturing” involved repackaging opium from elsewhere, mostly from British India via Hong Kong. As noted above, in those days the use of opium was perfectly legal, in both Canada and the U.S.}

1904

The Coast Guard cutter Grant, stationed in Puget Sound, is the first ship in the

Pacific to be equipped with wireless telegraphy. The purpose is to catch smugglers.

"Smuggling is largely carried out by the crafty skippers of small sailing craft and

steamers. They know every nook and inlet along the Sound. and in case it is

necessary to take several days on this trip, they have innumerable hiding places

where they can keep the Chinese under cover during the day ... It is at this point

that the wireless comes into play as a smuggler catcher. The Grant, steaming

along in the main channel, makes out a suspicious-looking craft skirting the shore.

The chances are ten to one that she is a smuggler. A wireless message is ticked

off to the customs officers at Port Townsend or Friday Harbor as the case may

demand. They put out in launches and lie in wait for the smuggling craft, whose

skipper has no reason to believe that she has even been sighted by the cutter."

[New York Times 1904-09-25; image from James G. McCurdy, Pacific Monthly 1910]

1924

For those being smuggled, having other contraband on board made the trip more dangerous. The Revenue Service was particularly eager to seize opium, which yielded large profits for the U.S. Treasury and promotions for Coast Guardsmen. During Prohibition, a cargo of illicit alcohol must have been equally risky for illegal Chinese immigrants. Dennis Noble in The Coast Guard in the Pacific Northwest relates this story: "The cutter Arcata, under the command of Boatswain L.A. Lonsdale’s "skillful and patient endeavor,… was able to make a good number of seizures (of illegal), many of them involving...craft (of higher speeds)." In June 1924, for example, Arcata was pursuing a speedboat and placed a shot across her bows. The rumrunner returned fire with small arms. The cutter then increased her rate of return fire and the smuggler’s boat exploded, apparently hit in her fuel tank. The boat was beached and it was found to contain contraband liquor, plus some Chinese were found onboard who were trying to enter the United States illegally."http://www.uscg.mil/History/articles/h_PacNW.asp

Photo from the official US Coast Guard website,

www.uscg.mil/history/webcutters/cutterlist.asp#W

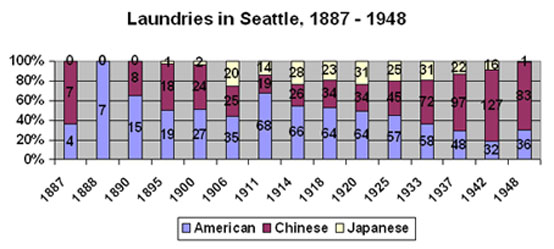

Does a Chinaman do your washing? 替你洗烫的是中国人吗?

“Does a Chinaman do your washing? If so you're not carrying out the principles of unionism.” Seattle Union Record

January 20,1906.

In 1906 Seattle residents with soiled clothes had a choice of laundries. Followers of union opinion, as expressed by the Knights of Labor in their newspaper, could have patronized any of the 35 American laundries in town. They could also have tried one of 20 Japanese laundries, which the Knights seem not to have placed on their blacklist yet. Or they could have defied the union and, like many Americans elsewhere, taken their clothes to a Chinese laundry anyway. There were 25 of those.

Ten years earlier, the Seattle Chapter of the Knights may have thought they had permanently cleared out all Chinese workers, including laundrymen. Through an orchestrated effort culminating in the January 1887 anti-Chinese riots, they closed down every Chinese laundry in the city. The Polk's city business directory for 1887, compiled before the riots, listed 7 out of the 11 laundries in Seattle as Chinese. However, in the 1888 directory, Chinese laundries had vanished. All surviving laundries, as required by union principles, were white.

This situation did not last. Seattle’s next decade saw a big rise of population and dressing standards, and hence of dirty shirts that needed the washing, starching, and ironing skills of hand laundrymen. So, in spite of labor opposition, the Chinese came back. Between 1890 and 1900 not only did the number of laundries in the city double, but almost half were run by Chinamen. There were also already a few run by Japanese. To fanatic white racists this must have seemed an ominous development.

The editors of Polk’s Directory for Seattle had a hard time deciding how to handle Asian ethnic laundries. Early editions always listed Chinese laundries separately from “mainstream” laundries, except immediately after the 1886 riot when there were no Chinese laundries to list. In 1892, when ethnic laundries again appeared as a separate category, Chinese and Japanese laundries were lumped together as “Chinese laundries”. In 1895 the Japanese were moved from the Chinese category to the mainstream, European-American one. They stayed there until 1906 when the Directory’s compilers, perhaps aware that the Knights and their supporters did not regard Japanese as honorary whites, chose to join both kinds of Asian laundries in a new separate category, “Chinese and Japanese.” It was not until the late 1940s that all laundries were listed as one category, specifying Chinese and Japanese in brackets after their laundry names.

Were the Chinese laundries singled out solely for racist reasons or because they also offered a different kind of service? Did Native Americans or African-Americans operate laundries at that time? Did Japanese and Chinese laundrymen regard each other as competitors or as allies? Why did the percentage of both kinds of ethnic laundries decline in 1910 for a few years? Why did Japanese laundries, which tended to be bigger than the Chinese kind, begin to decline in number as early as the 1930s?

(Data from Polk's and other city directories)

Perhaps the best-studied early collection of herbal medicines in the Pacific Northwest is the one preserved in the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria, BC. The collection formed part of a real Chinese herbalist’s shop from Victoria’s Fisgard Street called Man Yuck Tong, founded in 1905 and acquired by the museum in 1982 at the urging of Dr. David Lai from the University of Victoria. Dr. Lai recruited several of his UVic colleagues, including Dr. Nancy Turner, to help identify the shop’s 260 herbal medicines. [see http://communications.uvic.ca/edge/dean.html]

Man Yuck Tong shop, RBCM

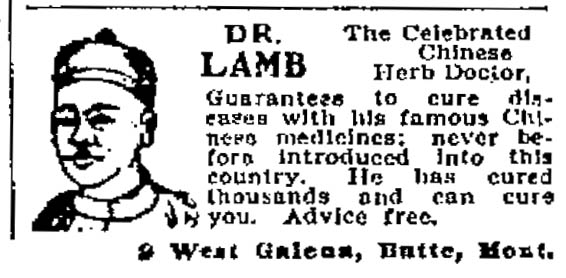

Dr. Lamb in Butte 林医师

Here is further evidence that in the Old West, Chinese herbal doctors

regularly treated Caucasian patients, in spite of widespread anti-

Chinese prejudice. The advertisement appeared on page 6 in the

September 20 1909 issue of the Anaconda Standard. Then

as now, exotic cures are more appealing than familiar ones, and

the desperate more likely to ignore cultural barriers.

Another Chinese herbalist who treated many non-Chinese patients was Dr. C.K. Ah Fong, who came to Idaho in the late 1860s. Beginning in Rocky Bar as a herbal physician, he moved to Boise in 1894. He seems to have done well in both places. In 1900 he sued the Idaho Board of Medical Examiners for refusing to license him. He won his suit, was officially licensed, and continued to practice traditional herbal medicine in Idaho until the 1910s or 1920s. For a picture of C. K. Ah Fong, see that entry on Washington State University's Columbia River Basin Ethnic History Project web site.

For more on the surprisingly long and complex history of Chinese medicine for non-Chinese Americans, see William M. Bowen, "The Five Eras of Chinese Medicine in California," in Susie Lan Cassel ed., The Chinese in America, pp 174-192. 2002, Walnut Creek, etc. Bowen suggests that one reason why Caucasian women often insisted on Chinese doctors was their gentle bedside manner, in contrast with the insensitivity of the average European-American doctor in those days. In western North America before the 1920s, almost all doctors were male.

Bowen cites numerous examples of Chinese physicians whose practices consisted partly or almost wholly of European-American patients. Despite opposition from newspapers and Western-trained doctors, Chinese herbalists and pulse diagnosticians thrived in several parts of California until the late 1930s, when the Japanese war in China made it difficult to obtain traditional medicines.

Advertisements for Chinese doctors often appeared in California newspapers. A typical advertisement of this kind, from an 1899 issue of the Los Angeles Times, claimed that a Dr. Wong "cured hundreds of people by his Vegetable Compound. He eliminates all the poison from thre system. He has cured many a hopeless case, and he can cure you. Seventeen years in city." Readers will note the similarity to Dr. Lamb's advertisement as shown above.

Detaining Asians at Seattle's "Angel Island," 1907-1916 西雅图的天使岛 - 临时移民审查站

The following article is paraphrased from John Litz’s “Seattle's "Angel Island" Reaches Century Mark,” which appeared in the North American Post on 1/1/2008. Although Litz has given us permission to reprint it, the Post owns the copyright. If that newspaper also grants us permission, we will present the complete article here.

The railway baron James Hill, builder of the Great Northern Railroad, not only had transpacific ships of his own but also managed to entice NYK lines, the chief Japanese shipping firm, to come to his piers and trains in Seattle. To make sure of this profitable trade connection, he constructed a new immigration center for Chinese, Japanese, and Asian Indians at the northern corner of Elliott Bay in Seattle, leasing it to the U. S. Immigration Bureau for a nominal fee. Most of the center consisted of detention facilities for immigrants, plus offices, a small hospital, and a canteen as well as offices for the agency. It was in use from late 1907 to 1916. Nowadays, although the Great Northern’s passenger trains and ships have long since disappeared, the building (at 1634 15th Ave. West) still exists.

It could house up to 120 detained immigrants as well as the Bureau’s regular staff, many of whom had moved from Port Townsend or elsewhere in Seattle. In line with the racist intent of the immigration laws, the great bulk of the detainees were Asians, Females were housed on the ground floor and males on the floor above. According to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the building was planned to have baths on each floor, to be heated with hot water, and to be "modern in all respects."

It did not live up to these promises. Already in June 1909, the Chief Sanitary Officer of Seattle announced that the building was one of the most unsanitary institutions in the city. According to the Seattle Star, it was “overcrowded and poorly ventilated" with “three washbowls provided for all of the fifty men imprisoned and in these same washbowls the men of all nationalities perform their daily ablutions. With the Chinese this includes the daily washing of their feet."

Litz points out that the center was not all bad. At Christmas in 1910, "100 Chinese, Japanese, Hindus and Europeans" detained at the center were given a banquet. For the women (including eight Japanese and five Chinese), the Chinese cook produced roast turkey and mince pie.

Most of the Japanese woman detainees came as picture brides for Japanese men in the Seattle area. The marriages were performed on the spot, with Immigration Bureau employees as witnesses. Between September 1907 and December 1908, more than 350 Japanese marriages took place at the center, performed by Japanese Buddhist, Baptist, Presbyterian, and Methodist Episcopal clergy. Most of the Chinese women detainees probably were already married, having come to join husbands of many years. Litz makes no mention of Chinese weddings at the detention center.

The center closed in January 1916 and the Bureau moved back to central Seattle. The building later was occupied by furniture companies and, at present, by Easy Mini Storage.

The picture of the building as of 2009 was taken by the editors while John Litz was showing us the building, which he located and identified several years ago as Seattle’s "Angel Island." He correctly sees it in the context of the notorious detention buildings for Asians on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay.

Thinking of the poems written on the walls of the real Angel Island, we asked the helpful manager, Kelly, at Easy Mini whether she had ever seen Chinese/Japanese writing on her walls. She said she hadn’t but that much of the original wall area was now hidden by later storage lockers. She promised to let us know if anything like that turns up.

The Immigration Center as a Furniture Factory, 1930s

The Former Immigration Center as Storage Facility, 2009

The former Great Northern line and piers opposite the Immigration Center, 2009

Smuggling Chinese between British Columbia and Washington.

West Shore 1889-11-09.

Chinese Laundry, San Francisco, ca. 1880

Chinese immigrant "dying of thirst in the desert" on the U.S.-Mexican border, from Ralph article in Harper's

U.S. Revenue Cutter Grant

Typical smuggler's sloop as seized by the U.S. Customs [in Port Townsend?], from J, G. McCurdy, Pacific Monthly 1910 p 187

"A small seizure of opium, 63 half-

pound tins, valued at $6 per tin"

Captain H. F. Beecher, the newly appointed (and unusually bribe-resistant) Collector of the U.S. Customs office at Port Townsend, pulls off a coup. Learning that steamers on the Washington-Alaska route often loaded illicit opium at Victoria on the way north and then brought it back south labeled as a staple commodity, he posts a pair of trusted men as spies in Victoria. In November they send word to Beecher that the steamship Idaho has loaded fourteen suspicious barrels marked "Ships Stores" at Victoria and proceeded north. When the Idaho reappears, it is searched rigorously. Only 933 pounds of opium are found, hidden in a washstand. What has happened to the rest? Luckily, Beecher's informants learn that most of it has been offloaded at Kassan Bay Fish Saltery at the south end of Alaska. Pressing the Revenue Cutter Wolcott into service, Beecher races to Kassan Bay. There he discovers the fourteen barrels, labeled "Salted Fish" but filled with smoking opium of the best quality. A total of 3,033 half-pounds of the drug are seized, which net the government about $40,000 when resold. Up to that time, it is "the largest seizure of any commodity ever made in the history of the Customs Service" [J. G. McCurdy, Pacific Monthly 1910 pp 1886-7]

Another view of the USRC Wolcott. By 1890s standards she was slow and out of date. McCurdy, Pacific Monthly 1910 p 192

Victoria's vile detention facility 域多利华人拘留所

The following quotation is from the Annual Report of the Surgeon-General of the Marine-Hospital Service for the Fiscal Year 1895. The writer is J. O. Chubb, Passed Assistant Surgeon, Marine Hospital Service.

It would be nice to think that Chubb is being sarcastic when he writes "A Chinaman prefers the floor to the bed, I believe." But sadly, he seems to be dead serious: Chubb and the Canadian immigration authorities were well matched in indifference to the suffering of others, Chubb's medical training notwithstanding. Angel Island at San Francisco may have been bad. Victoria [location may have been called Cold Harbour] was worse.

Annual Report of the Surgeon-General of the Marine-Hospital Service for the Fiscal Year 1895, Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1896, pp 353-4.

Port Townsend's fine but doomed detention house 砵党顺华人拘留所

The facilities for housing and processing Chinese immigrants were better at Port Townsend. Until 1907, all foreign ships inbound for Puget Sound ports had to stop first at Port Townsend to clear any Chinese passengers and crew before proceeding to Seattle, Tacoma, etc.

In 1901 or 1902, the Federal Government leased a fine building in downtown Port Townsend as a Chinese Detention House. However, 1904 rumors began to spread that the government's Chinese immigration facilities would be moved to Seattle. As noted above, this rumor came true three years later. The Port Townsend Chamber of Commerce tried to stop the move as soon as they heard about it. In a letter to Addison G. Foster, their senator in Washington D.C., the Chamber argued vigorously for keeping the detention facility in Port Townsend. The current facility at an annual rent of $1000, they wrote,

The Chamber went on to argue that Port Townsend was a better place to watch for smugglers and more convenient as a port for shippers not based in Seattle. The latter point might have weighed heavily with Senator Foster, a Tacoma businessman.

They were right about the cost of finding an equivalent building in Seattle. The one eventually chosen by the Immigration Service at the northern corner of Elliott Bay was inferior to the one in Port Townsend. But, then as now, political clout trumped administrative rationality, which meant that the days of Port Townsend's detention building were numbered. James Hill on behalf of his Great Northern steamship and railroad company had much more clout than a collection of Port Townsend shopkeepers. Hill wanted the Chinese facility to be near his piers in Seattle, and no number of complaints to senators could change the outcome.

Port Townsend Daily Leader 1904-03-09, p 1; 1904-03-31, p 1. The former Chinese detention building still survives. It was located by the editors on April 15 2009 with the crucial help of archivist Marsha Moratti and other staff at the Jefferson County Historical Society Research Center. They were the ones who located a news clipping that mentioned a celebration in 1904 at the Detention House, "formerly the Clarendon Hotel," which enabled them to pinpoint the location. Interestingly, the Detention House was only a block from Port Townsend's Chinatown. In contrast, San Francisco's and Victoria's Chinese detention facilities were built at isolated quarantine stations, far from settlements of any kind.

is a three story brick building of solid construction, having stone foundations and two large basement rooms; a frontage of fifty feet which contains two large rooms, with kitchens, bath rooms and toilets on the ground floor. There are thirty-three large and light rooms on the second floor and the third floor, all fitted up with special reference to the detention business with grating at windows and every way secure. The building is of sufficient size to afford spacious accommodation for the various offices of the officers, as well as store rooms, and will house one thousand persons with entire comfort, and two thousand when necessary.

Such a building could not be procured in Seattle for less than $15,000 a year. In addition the cost of operating such a building in Seattle would be from half as much again to double what it is here...

The Chinese detention barracks [in Victoria, B.C.] are about 300 yards over the hill from the executive building [of the quarantine station]. It is a very large, flat building, cut up into three large compartments. each about 40 by 70 feet. There are washtubs with water supply, kitchen, and four small storerooms. It is estimated that about 300 persons can be cared for in this building in the Chinese fashion. A Chinaman prefers the floor to the bed, I believe. There is a large privy house over the water's edge for use instead of water-closets. The kitchen is supplied with a large hotel range. There should be shower baths, but there are no baths of any kind.

Government officers who have visited the building pronounce it the best and best managed of any in the United States except the station at Ellis Island in N.Y. harbor. It is even doubtful if the San Francisco building to be erected [at the quarantine station on Angel Island in 1910 -- eds.] at a cost of $200,000, will exceed it in perfection of arrangements.

Lewis Building, former home of Chinese Detention facility in Port Townsend, on Water Street, a half block from City Hall

Walla Walla: many dead Chinese were not sent home

落叶不归根 : 抓李抓嚹早期华人墓地

They say that before World War II the bodies of deceased Chinese were almost always shipped back from America to China. But there are exceptions -- for instance, Walla Walla's Mountain View Cemetery, which has a good many early Chinese graves. The earliest, dated April 1919, is that of Mr. Wei En 魏恩, a native of Taishan in Guangdong.

Chinese graves in Mountain View Cemetery, Walla Walla,

Washington State

SYMPOSIUM ON ASIANS AT SEATTLE'S ALASKA-YUKON-PACIFIC EXPOSITION OF 1909

Shootout at Sedro-Woolley: Customs Officers Fight over Smuggled Chinese (and Opium), 1891

A bonanza for newsmen occurred on July 26, 1891, just north of the town of Sedro-Woolley, formerly "Bug," about 30 miles south of the U.S.-Canadian border. It all began on July 25, when a Seattle-based customs inspector, Z. Taylor Holden, proposed to a King County deputy sheriff, George W. Poor, that the two of them should go the next day to the Skagit area to catch some smuggled Chinese. How Holden knew that the Chinese would be there on that date, at a spot so far south of the border, is not clear. Neither are Poor's motives. As a King County deputy, he could hardly claim that immigrant smuggling in Skagit County was any business of his, and he would have no police authority there anyway. It seems likely that his and Holden's real target was not illicit Chinese but opium. That is what he told his boss, the sheriff of King County, before he left (Sacramento Record-Union, July 28). It made sense. Smuggled opium brought a generous bounty to the agent who captured it, even if he failed to keep some to sell himself.

Whatever the explanation, Poor accepted Holden's proposal, and the two of them set off the next morning for Skagit. Upon arrival they encountered two of the other characters in the drama, the locally based customs inspectors, J. C. Baird and James Buchanan. The two teams conferred briefly and agreed to conduct their searches separately, Baird and Buchanan going in one direction and Holden and Poor in the other.

All was quiet that evening until Baird and Buchanan, who had decided after all to go in the same direction as Holden and Poor, heard something. Sure enough, it was a line of men coming along the road from the north. Pulling out their revolvers, Baird and Buchanan called on them to stop. The others, who included Deputy Poor and a notorious smuggler named Jake E. "Cowboy" Terry, opened fire. Buchanan and Baird fired back. Baird was wounded in the head. Terry was hit four times but not hurt fatally. Poor was killed. Buchanan came through unscathed. Holden claimed not to have been there at all, saying that he had decided at the last minute to remain at a saloon in Woolley. The Chinese, of whom there seem to have been thirteen, were also unhurt and not particularly frightened. Nine of them were recaptured the next morning on the outskirts of town as they tried to buy tickets onward to Seattle.

The media had a field day, denouncing everyone in sight but, for the most part, keeping quiet about the opium. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer (July 28), from which Washington State's on-line historical encyclopedia, HistoryLink (http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=5485) took most of its version of the affair, seems to have sided with Holden and Poor, regarding Baird as the chief villain. The Blaine Journal (July 30), whose reporters must have known Buchanan and Baird personally, took their side, claiming that the Seattle papers "have endeavored all through to cover up the truth and avoid committing themselves." All agreed that Terry, a professional smuggler, was a bad apple but could not decide whose side he had really been on. The Victoria Daily Colonist (July 30), whose reporters also may have known the protagonists, further complicated the issue, stating that "Holden is entirely free from suspicion of implication in the shooting, despite Baird's emphatic statement. Terry has confessed. Holden and Buchanan are now the best of friends."

Sedro-Woolley was (and is) not an important town. However, it is strategically located at the junction of the few easy land routes from the north to the Seattle area. This map is from Google Maps.

ON OTHER PAGES OF THIS WEBSITE

> Should the subject be taboo? 秘密社会可谈不可谈? 10/1/09

> A 19th century secret society manual in Clinton, B.C. 加拿大卑斯省天地会会簿 10/1/09

> Membership certificates meant for concealment 洪门致公堂腰牌 8/13/10

> A meeting notice you couldn't refuse 见签岂有不到会 8/15/10

(1) 1866 The Oldest Surviving Chinese Temple in North America [1/25/10]

(2) 1866-1892 The North God in North America. [10/26/10]

(4) 1885 The CCBA's Shrine in Victoria, BC: Prestige from home town heroes [12/14/09]

(5) 1909 Kong Chow Temple in San Francisco: Prestige from famed diplomats [1/26/10]

(6) n.d. Cast iron bells in North American Chinese temples [updated 3/25/10]

(7) 1911 An art nouveau landmark: the Hook Sin Tong Building in Victoria [5/24/10]

(8) 1870s-1904 Suijing Bo in the Northwest: A once-obscure deity makes it big [7/18/10]

(9) 1874-1908 “Tianyun”--Secret temple dates for a revolutionary cause [7/22/10]

a. Victoria: the largest opium making center outside Asia [11/16/09]

b. Refining and packaging opium for sale 提煉. 包装 [8/9/09]

c. Opium brand names [updated 11/2/09]

d. More opium brand names: from gold mining sites in the Cariboo [updated 01/18/10]

e. Opium cans or "tins" [8/14/09]

f.. 1920s-30s opium cans of the prohibited period [10/5/09)

a. Opium equipment in the US, 1896 煙具 [8/1/09]

j.. The opium addicts of Albany, NY [12/21/09]

[7/15/09]

|| (N) Chinese Identity

(2) The First "Chinatown" [7/2/10]

(a) An early herbal doctor in John Day, Oregon [updated 4/20/11]

(c) Dr. Lamb in Butte and Dr. Ah Fong in Boise [updated 10/5/09]

(with new statistics on changes in the number of Seattle's Chinese and Japanese

Free enterprise at work on the U.S.-Canada border.

(a) Ralph investigates immigrant smuggling on the border in 1890 [updated 3/11/09]

(b) Annals of Northwestern Smuggling by Sea and Land [latest entry 4/10/09]

(d) Joking about a smuggler murdering immigrants, 1880s [posted 2/13/09]

(a) Seattle's "Angel Island", 1907-1916 西雅图的天使岛 - 临时移民审查站 [posted 1/15/09]

(b) Victoria's vile detention facility [posted 4/14/09]

(c) Port Townsend's fine but doomed detention house [updated 4/16/09]

(a) Chinese fishermen In Washington Territory [posted 11/10/09]

(b) Chinese workers at Columbia River canneries [posted 11/10/09]

(c) Were Chinese fishermen greedy and irresponsible? [posted 11/10/09; updated 02/08/10]

(d) Were those fishermen Tankas? [posted 11/17/10]

( 版权 Copyright is free for non-profit use: : click here for more information.)

Chinese Fishing in Washington Territory

Were Chinese fishermen environmentally irresponsible?

Chinese Workers in the Columbia River Canneries

On this page (click on topic for details)

Chinese shrimp fishermen in San Fran-cisco Bay, Harpers Wkly 20 Mar 1875

On other pages (click on topic for details)

|E| Secret Societies

|G| Shrines

|L| Landscapes

|N| Chinese Identity

A-Y-P Exposition Place Names First Chinese Why Chinese Died Secret Societies Prince Tsai Comes

Most of the research presented on these pages is original, based on primary sources.

Shrines Emperor Opium Violence Landscapes Cemeteries Women

|A| |B| |C| |D| |E| |F|

|G| |H| |J| |K| |L| |M| [P]

Were those fishermen Tankas?

This page was last updated: August 30, 2018

For more on Doc Hay at Kam Wah Chung, click here. See also Jeffrey Barlow and Christine Richardson, China Doctor of John Hay, Binford & Mott Publishing, 1979. It is still on sale at the Kam Wah Chung Museum.

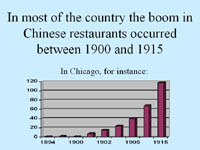

Chinese restaurants aimed at non-Chinese customers revolutionized Chinatown economies in the East and Midwest in the early 1900s, In the Northwest, however, they not play as large a role.

For the reasons why, go to the "Labor" page of this website, or click here.

The webpage on these themes has been moved. Please click here to see them