=========================================================================================

Summary (Afable and Weibel)

Performers, Interpreters, and the Showman Onstage and Offstage

at the Pay Streak's "Igorrote Village"

Patricia O. Afable and Deana Weibel

=========================================================================================

Summary (Aoki & Ho)

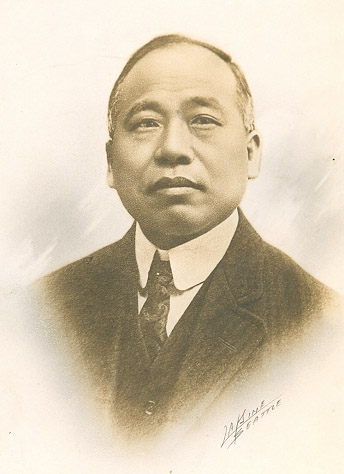

Tatsuya Arai Concessionaire for the 'Streets of Tokio' at the AYPE

Shea Shizuko Aoki & Chuimei Ho

Arai in fact was not the sole proprietor of “The Street of Tokio”. The business was owned by two other Seattle Japanese businessmen and community leaders, Masajiro Furuya and Charles Takahashi. These three were usually more competitors than allies. But they joined forces and formed a company called Kyosan-kai in January 1909, which literally meant Street of Tokio. It seems that Arai alone was made to bear the PR and marketing responsibilities for AYPE. He and his young wife, Kan Arai, attended many AYPE official receptions.

Tatsuya Arai came to Seattle in 1894 and died in 1922, buried at Lakeview Cemetery. His wife, Kan, came to join him in 1900. Their first child, Clarence, was born in 1901. Then came Fumiya in 1902, Tom in 1904, and Baby Lillian in 1908. Lillian is still alive, in California. By 1909 Tatsuya Arai was already a leader in the Japanese community. He was the first president of the Japanese Association and the Japanese Commercial Club in Seattle, in addition to being a banker. In fact, he was the only Asian sitting on the AYPE committee.

The Formosa Tea House also served Chinese tea and Japanese rice cakes. It seems Tatsuya was keen on doing food business at AYPE. Basically he was a businessman who did not want to miss out opportunities. He wanted all kinds of customers. At one corner of the “Street of Tokio” he even put up a coffee shop which sold ice cream as well. It makes sense for Seattle Japanese to focus on food and drinks at the Fair.

Formosa, or Taiwan, by then had been a Japanese colony for 14 years. The Formosa Tea House at AYPE was operated “under auspices of Formosa Government, Japan”, as indicated in the official Japanese Exhibits handbook. It is interesting that the Arai managed to persuade the Japanese government let him use the name of the colony commercially. And semi-officially as well - on the Open Day of the exposition Japanese and American sailors were given lunch at Formosa Tea House. What exactly was the relationship between the Japanese government and Japanese residents in Seattle? How did they cooperate, or divide their roles, at AYPE? These are questions without easy answers.

Another Frank Nowell picture, #4280, may throw some light. It shows a group of Japanese, dressed in suits and boiler’s hats with a AYPE badge, posing in front of the Japan Building. Tatsuya Arai is the first right of the 2nd row. The Seattle Japanese community must have been very proud of being Japanese at the Fair. After all, Japan was the only official participant from the other side of the Pacific rim. Here they are, carrying two flags – one Japanese and one American?

But the community must have also felt the need to make the point that they were not Japanese from Japan. On the left is a square banner which reads “Japan-U.S. Friendship” in Japanese and “Seattle Local Japanese” in English.

=========================================================================================

Summary (Bronson)

Asian Americans and Images of Asians at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition

Bennet Bronson

Following the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, most world fairs in the U.S. were formally divided into official and unofficial sections generically called midways. Official national exhibits in the former served, naturally enough, the perceived interests of the governments that sponsored them. However, unofficial national exhibits on midways had more disparate goals. Often termed “villages,” such exhibits aimed at entertaining fairgoers, making money, and – where possible – advancing the interests of the exhibitors. At later U.S. fairs, many such exhibitors were ethnic Asians.

At the AYPE, as had been the case at all fairs since Chicago's, the Chinese Village was under the control of resident immigrants. Interestingly, so was the Japanese Village, but this was the first time in any city that American-based Japanese had financed and managed a world fair exhibit of their own. The only Philippine village at the AYPE was that of the “Igorrotes,” the management of which was not in Filipino hands. And the AYPE did not have a Hawaiian village, perhaps due to feelings in Hawaii about image problems caused by the exploitation at other fairs of hula-hula dances and the like.

The very commercial Igorrote Village was a financial success but, surprisingly and due to the showmanship of talented Igorot participants, managed to project a view of Igorots at variance with the popular notion of them as dangerous, under-evolved, and dumb. The Chinese Village was successful, not so much financially as in conveying a positive picture to white Northwesterners of a previously despised ethnic group. The success of the Japanese Village, however, was mixed. It made money. It showed advantageously the organizational skills and heritage of U.S.-based Japanese. But the official activities of Japan's government had a negative impact. That government's proud display of its colonial ambitions and newly revealed military power might have helped immigrant Asians in the short term. However, in the longer term the effect of such displays would be disastrous for Japanese Americans .

=========================================================================================

Summary (Cordova)

Filipinos in Washington and the AYPE.

Dorothy L. and Fred Cordova

Fred Cordova will present a summary and analysis of his research on the "Igorotte Village" during the 1909 Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition at the University of Washington. Historic photographs of the Village from the UW Special Collections and Smithsonian Institution will enhance his presentation. Dorothy Cordova will address the impact derogatory promotional

materials about Igorots had on Filipinos living in Seattle for the next 40 years.

=========================================================================================

Summary (Daykin)

Calming the Waters of Japan-U.S. Relations through Commerce:

The Reception of Shibusawa Eiichi's Trade Commission at the A-Y-P

Jeffer Daykin

In considering Japan’s participation at the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, it is essential to consider that the fair took place in the wake of furious anti-Japanese immigration sentiment that had broken out in areas along the Western United States and Canada in 1907. Though Seattle’s extensive population of Japanese residents was generally spared the brunt of this violent agitation, concerns over continued Japanese immigration lingered.

Japan could rightly present itself as a world power after its victory in the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War. It asserted this fact not just by contributing a national pavilion and extensive collection of exhibits at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, but by stationing a warship at Seattle for the duration of the fair. Yet to assuage such fears and provide a constructive vision of Japan-US relations, the Japanese government contributed a national pavilion and an extensive collection of exhibits to the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. In addition to such official participation, a non-governmental commission of prominent Japanese businessmen, led by the renown industrialist Shibuasawa Eiichi, arrived in Seattle in time for the fair’s Japan Day celebrations and then embarked on a nation-wide tour of United States’ Chambers of Commerce in order to affirm the potential for mutually beneficial transpacific trade. This paper will examine the events surrounding this trade commission’s visit as well as its reception.

=========================================================================================

Summary (Ho)

How Ready Were the Chinese and Japanese Communities in Seattle to join the AYPE?

Chuimei Ho

Seattle’s two leading Asian immigrant groups, the Chinese and Japanese, decided to participate in the city’s first world’s fair, in spite of the fact that Seattle in 1909 was not a friendly place for them. Hostile examples were plentiful, although there were also occasional friendly gestures offered by businessmen, clergies, liberals, and other minorities. At the end of the AYPE, by all accounts, the two immigrant groups had pulled it off. How did they handle the prevailing hostility and make themselves equal, or almost equal, members of the international exposition? This presentation examines their strength and strategies before the AYPE took place.

Details in strategies varied between the two groups but the principles behind their actions were similar: (1) utilize existing goodwill, (2) neutralize attacks, (3) adopt counter-hostility defenses, (4) build community assets.

But they may have been concerned with more than just being accepted by Americans. In those early days, even when “Asian American” was not yet a meaningful term, Chinese and Japanese residents began to worry about who they were and how they could reconcile differences in American and home-country values. The AYPE was one of the early testing events in the Pacific Northwest that forced the immigrants to deal creatively with this issue.

=========================================================================================

Summary (Hoverson)

Hawaii at the Fair

Martha Hoverson

=========================================================================================

Summary (Kay & Bronson)

Lew G. Kay, the Chairman of China Day at the AYPE

Richard Kay and Bennet Bronson

China Day, on September 13 1909, marked the high point of the AYPE for Washington's Chinese community. The Program Chairman of China Day was Dick's father, Lew Kay. Although only 24 years old, he was given a lot of responsibility. His job as program chairman meant organizing (1) the China Day Parades, (2) the China Day floats, (3) the China Day luncheon at Ah King Restaurant in the Chinese Village, and the China Day speeches and entertainment in the AYPE Auditorium. In his own speech, delivered in faultless educated English, he thanked Americans for their friendship and for the decision, just made by Congress, to use the Boxer Indemnity money owed by China to the U.S. for bringing young Chinese to study in American universities.

So Lew Kay could give diplomatic speeches. But why was he chosen for the job in the first place? Goon Dip, a prominent businessman in Portland and Seattle, did the choosing. In overall charge of the event, he needed a local man to run the program. Lew Kay clearly was well qualified. He had just graduated from the University of Washington and had already been involved in representing American Chinese on important occasions.

========================================================================================

Summary (Kerlee)

Japanese art and crafts at the AYPE – what beauty, and messages, do they convey?

Dan Kerlee

Visitors to the AYPE were treated to a wealth of Japanese culture through architecture, graphical imagery, and thousands of objects that ranged from the mundane to the sublime. With four major venues distributed over a wide area of the grounds, no participant could miss their beauty or fail to receive their influence.

By 1909 Japan had a long history of involvement with exhibitions in the West as well as at home. Its rising stature in international affairs, together with a deep and long-standing interest in Japanese culture and commercial potential among the fair’s planners helped create a rich atmosphere of cultural exchange. Much of this took place though exposure to objects of commercial and artistic creation, covering a wide range of categories. Regardless of background or standing, there was something Japanese for every visitor to appreciate. Through objects of every type Japan’s culture had a significant impact on areas of the Fair’s areas of commercial development, foreign relations, landscaping, performing arts, and fine and applied arts.

The AYPE really took place in related and sanctioned events all over the city and when we come to our subject the story is no different. Japanese goods and AYPE souvenir objects were available in many locations in Seattle and so it is not always useful to say that something was observed, enacted, or purchased on the fairgrounds. Department stores in downtown Seattle, for instance, list paper fans and umbrellas among their souvenir goods for sale. On the grounds, though, there were two main sources for objects that have survived today: The Streets of Tokio, located on the lower Pay Streak, and the main Japanese Government building.

=========================================================================================

Summary (King)

My Grandfather, Ah King, the Only Chinese Concessionaire at the AYPE

Howard E. King

=========================================================================================

Summary (Nicola)

The Chinese Community at the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition

Trish Hackett Nicola

This presentation is a summary of the Chinese involvement in the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition.

Finally, there will be a summary of the financial aspects of the exposition—how it almost made a profit and the legacy of the exposition to the Chinese community.

=========================================================================================

Summary (Oshima)

Japan: The Architecture of Abodes Abroad

Ken Tadashi Oshima

=========================================================================================

Summary (Quizon)

Of “dead exhibits” and living things: lessons from the Philippine ethnological

displays at St Louis and Seattle

[PRESENTATION CANCELED BY QUIZON, 09/01]

Cherubim Quizon

This paper will examine the parallels and divergences between the nature of Philippine ethnological displays in two early 20th century American World’s Fairs: the Louisiana Purchase Exposition at St Louis in 1904, and the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition at Seattle in 1909. In what way did the exclusive role of the United States government in the display of living Filipinos and their culturally/scientifically meaningful artifacts in St Louis shape the more divergent exhibition modes that played out in Seattle five years later? In this transition from the realm of serious education and other truth claims in the St Louis colonial exhibits to the multiple realms of both government and “entertainment ethnology” in Seattle, what kinds of economic and social arrangements made the repeated displays of living Filipinos, possible and, from the point of view of the Fair organizers, extremely desirable? If we actively consider new research on the communities of origin of these individuals and their perspectives on participating in displays of their own culture that are nevertheless explicitly authored by others, what kinds of insights might be gained from conflicting truth claims that ostensibly originate from early 20th century American and European anthropological practices? What kinds of implications arise when past practices are considered alongside contemporary anthropological representations of living peoples on one hand, and tourist-oriented representations on the other? This paper will broadly examine the role of state institutions such as the Smithsonian as well as key private entrepreneurs in shaping the customary arrangements that facilitated the staging of both living Filipinos & non-living/artifactual ethnological displays in the Seattle exposition.

=========================================================================================

Summary (Smith)

The Chinese Exclusion Act in the era of the Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition

Sarah Nelson Smith

By the time the Alaska Yukon Exposition opened in June of 1909, there were thousands of Chinese Americans living in the Pacific Northwest. Chinese settlement began in this region in the 1850s, along with other non-Native people. By 1909, Chinese neighborhoods had been bustling for years. But the decades prior to the AYPE held a mixture of antagonism and ambivalence from other settlers towards the Chinese community. The Chinese Exclusion Act became law in 1882 as the first law excluding particular persons from immigrating to the United States. Though the U.S. Government worked to stymie the population of Chinese people in this country, the Chinese communities did thrive.

This paper will discuss the realities of entering the Port of Seattle as a Chinese person in 1909, the year of the AYPE. By examining the records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service and other primary sources, we will look back at the history of the Chinese Exclusion Act and familiarize ourselves with the operations of the Seattle office. The Pacific Northwest was experiencing an economic boom following the Klondike Gold Rush, and the AYPE flaunted those broadening horizons. But the Chinese Exclusion Act kept the formal distance between the societies and economies of the United States and China, and did so for several decades after the Pay Streak was gone.

=========================================================================================

Summary (Song)

Chinese Architecture at the AYPE and in Early Seattle

Tina Song

=========================================================================================

Summary (Rash)

Asian Imagery at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition and in Seattle

David A. Rash

At the time of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, Seattle had the largest Asian-Pacific community in the Pacific Northwest and one of the largest such community on the West Coast. Within this community, only the first Seattle Buddhist Church gave any outward expression of the architectural heritage of Asia. This had not always been the case in Seattle, and after the A-Y-P, the area now known as the International District, which was the twentieth century home of Chinatown and Nihonmachi, would slowly acquire visual accoutrements of Asian architecture.

This paper will examine some of the causes for the disappearance of Asian imagery from Chinatown and how this affected Nihonmachi. It will also look at the various examples of Asian architecture that were included at the A-Y-P, as well as the public reaction to these examples. It will also show various examples of post-A-Y-P buildings in the International District where Asian imagery was incorporated into their design and how these projects were influenced by the A-Y-P, as well as other factors. A particular focus will be the iconic Maneki Café as it existed between 1913 and 1941 in the former Oriental-American Bank building.

=========================================================================================

Summary (Whitman)

Masajiro Furuya:

Aggressive Businessman, Gentle Gardener, and Bainbridge Islander

Michele Whitman

I Furuya Resort House / Whitman Home - visitors and history

I live in the 105 year old “Furuya Resort House” on Bainbridge Island. Over the years we have become aware of the significance of Furuya’s business and social position in the Japanese community. The history and personal information provided to us by visiting employees, their children, guests and past owners has been so valuable. Over the last 33 years we hosted a Japanese Community Picnic and had many visitors with connections to the house. Our most memorable visit was a celebration of life for a previous owner, Sheigeko Uno’s mother. She had requested her ashes be scattered in the Atlantic and at Crystal Springs which was her favorite place. We were honored to fulfill her request.

2 Furuya - from tailor to million dollar business empire

1890, Furuya a 28 year old tailor arrived in Seattle at a time the Japanese community was growing, providing him with unlimited business opportunities. The Furuya Company was involved in many enterprises including grocery stores, real estate, construction, printing, postal service, banking and a Tea House. His business branches served Yokohama, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana. He was a frugal, strict, Christian man demanding the discipline and obedience of his employees. This included a 10-hour ,7-day work week, a dress code, and no vacations, except once a year when employees and their families picnicked at Furuya’s Crystal Springs home on Bainbridge Island.

3 AYPE - Japan Day.

The official group picture of the local Japanese merchants taken in front of the Japan Building, showed their unity in making Japan Day at the AYPE a successful business and social event. Furuya was one of three big owners of “Kyosan-Kai” which ran the “Street of Tokio” at AYPE. He frequently attended AYP receptions and toured with Japanese dignitaries. He imported souvenirs with his “Furuya Co.” trade mark. His contributions as a business and community leader played a major part in this event.

5 Final Thoughts - the man and his empire

Throughout the 20’s he was the most prominent and powerful Japanese business man having built a million dollar empire. By the early 30’s he was bankrupt, disgraced and poor. He returned to Japan were he died at the age of 75.

Living in his “Resort House” for the last 33 years, we have acquired a great appreciation and understanding of the business and social contributions he made to the Japanese community. We continue to enjoy the vision and beauty he created 100 years ago. Our thanks to Kaora Ichihara, Deborah Ono and her aunt Lillian, Eddie Harrison, Irene Shigaki, and her aunt Yuki Kawakami who have provided us with valuable information and photos.

Visitors Welcome. Email us at “ fmw5071@comcast.net”

=========================================================================================

SUMMARIES OF SYMPOSIUM PRESENTATIONS

(These summaries vary in length and finally, as of 9/6, are more or less complete, although some are longer than others. They are arranged alphabetically by the speaker's surname. Images are still being added)

Other symposium pages: Asian-Pacific Perspectives on the AYPE

The "Igorrote Village" in the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition's Pay Streak showcased the cultural activities and performances of about 40 people from the Bontoc region of the northern Philippine highlands. They arrived in Seattle in early 1909 with a showman from Detroit, Richard Schneidewind, who had contracted with them and arranged for their journey from the Philippines. A small set of Bontoc-born interpreters, led by the most experienced English-speaker of them all, the 21-year old Antero Cabrera, accompanied them. For most of that year, the "Igorrotes" built their "Village," including thatched-roof houses imitating their own homes, and stone-walled terraces that were said to resemble the irrigated rice fields of their home region. On a stage and in adjoining grounds, they performed traditional dances and gong music, and staged ceremonies, mock battles, and trials. As part of their daily routine, they displayed their weaving techniques, cooking practices, and other portrayals of (as one brochure put it) "the life, manners, customs and industries of these remarkable children of nature" to the Pay Streak audience.

Richard Schneidewind

This account. by two anthropologists, attempts to recover some of the lives and historical experiences of the indigenous participants in the 2009 "Igorrote Village" at the AYPE and their showman, Richard Schneidewind. We draw on oral histories from descendants of the performers and Schneidewind, as well as on archival documents, including records from the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration and those collected by Schneidewind's family. Photographs and newspapers of the time document the "Igorrote" displays, their mode of advertising, and some of the public response to them. Family stories and the body of documents taken as a whole also reveal to us how, during the long journeys to the Fairs, the Bontoc performers developed viable working relationships with Richard Schneidewind and his family that made life "onstage" and "offstage" comfortable and stimulating collaborative experiences.

Schneidewind, a veteran of the Philippine-American War, had met some "Igorrotes" while managing a cigar concession at the 1904 St. Louis Fair. Their biographies allow us insights into how colonialism was played out in the lives of northern Philippine highland peoples and this son of working-class German immigrants to America. For one, highland peoples were accorded marginal status in a society where most lowland neighbors had converted to Christianity in the Spanish period. In the early 1900s, Bontoc people going to the Fairs were defying their elders and the missionaries and taking these unprecedented chances to earn money and to see the world in the company of relatives and friends. The oral and archival accounts hint at many possibilities of accommodation and appropriation in a situation that was full of opportunity as well of potential exploitation. An important outcome of these early journeys was an enduring desire among descendants for formal education and the social mobility that it promised. Today, several thousand Igorot descendants in North America celebrate their identity and heritage as heirs to this legacy.

.

Poster used for the 1906 fair in Los Angeles

A visitor to the AYPE would have found the following places displaying Japanese culture on the fairgrounds proper:

a. The Japan Exhibits Building. Put up by the Japanese government, with several hundred vendors from Japan.

b. Nikko Cafe. Concessionaire Kushibiki, a Japanese businessman with much experience in world's fairs.

c. The Formosa Tea House. Concessionaire Tatsuya Arai, also a Seattle Japanese resident.

If the visitor ventured onto the Pay Streak area, he or she would find that close to the pier was the “Street of Tokio”, the concessionaire is also Tatsuya Arai. No doubt both Kishibiki and Arai were ambitious businessmen. But what else did they do? What did they choose to show at AYPE? What made them think that they could do something better than that the Japan government could? While Kushibiki 's base was in Tokyo rather than in Seattle, Arai's was a Seattle resident.

Tatsuya Arai and his staff, AYPE

Tatsuya Aria and Family

Frank Nowell’s official photograph #4771 shows a group of Japanese posting at the back garden of the Formosa Tea House? The Street of Tokyo? at the AYPE fairground. The group includes 4 children, 6 women (4 in identical, plain kimono), and about 40 men dressed in American style. A sign at the upper left hand side reads “Japanese Fast Meals” in Japanese. The group of woman in plain kimono must have been the waitresses for the Tea House. Tatsuya Arai himself was standing on the right hand side, holding the hand of his 2nd son, Tom. Clarence must have taken to many other community events as well, as shown by photos of the family album.

Clarence Arai followed his father's step to become a community organizer. He was a scout master in 1925 and the president of the Japanese American Citizen League in 1938, apart from being the first Japanese-American graduate with a law degree from the UW. But later on in 1942 when American-Japanese were imprisoned at concentration camp, he was criticized by the community as a collaborator with the U.S. Government. To those who know him, Clarence Arai was an honorable man who tried to make the inevitable internment as peaceful as possible for his community. The redress issue puts him and his family in the dark. Today his family still lives with that shame.

While the AYPE provided opportunities to bring communities together, Internment divided families and the communities

Chinese Village, Trans-Mississippi Exposition, Omaha, 1898

Kushibiki’s “Fair Japan” village, Pan American Exposition, Buffalo, 1901

Buddhist Mission Society, 1012 Main Street. Shea Aoki Collection

Mrs. Goon Dip in a Western outfit

Rev Inoyue and the Japanese Mission 1908?

The AYPE was Hawaii’s first big exposition since the overthrow of the monarchy in 1893. In requesting US government funding for the AYPE, the Territorial representatives stressed their desire to use the Exposition to promote homesteading as a way to encourage white settlers to “Americanize” the islands.

Homesteading programs in Hawaii amounted to little more than window-dressing to appease Congress, but the Territory was very serious about promoting its plantation crops, particularly pineapple. Island growers were in the midst of a campaign to create a “Hawaiian” brand for their product. A group of young Hawaiian ladies was brought to Seattle to serve pineapple to fair visitors. They and the Hawaiian musicians who performed in the Hawaii Building were the Hawaiian face of the Territory’s exhibit. Exhibits of traditional Hawaiian life and culture were confined to the Smithsonian’s display of artifacts in U. S. Government Building. Hawaii had no presence on the Paystreak in Seattle. Hawaiian hula dancers who performed at Chicago in 1893 and in later fairs were seen as a source of shame by the local elites. And though hula’s influence on the popular image of Hawaii was indelible, the government and business interests wanted to present a different picture. The AYPE was also a venue to promote tourism, then still in its infancy, and the Hawaii Promotion Committee used innovative displays and the new medium of motion pictures to showcase the attractions of the islands.

Pauahi Kamokei & Jennie Kapahu.

Hawaiian churchmen visited AYPE enroute from a conference

As other papers in this symposium show, China Day was a great success, and this made a difference to Chinese in the Pacific Northwest. But another question is relevant here. Did China Day and the AYPE make a difference to Lew Kay himself? He got a job in China after the Exposition. After a couple of years he returned briefly to get married. Then back to China. Finally home to Seattle again for good. Clearly, he had decided to be an American. His experiences at the AYPE, working closely with Americans of other races, must have helped to convince him.

However, he had another reason for returning to America, also connected to the AYPE. The reason was a female one. Here she is on an AYPE postcard sent by Lew Kay to a friend. She was a girl named Rosaline, Goon Dip's oldest daughter.

Three years after the AYPE, Lew and Rosaline married in the American style and lived happily ever after. Dick was born a few years later. Lew and Rosaline Kay were Dick's father and mother. Dick's grandfather was Goon Dip. So Dick owes more than most people do to the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition.

Lew Kay in Tangshan, China, 1912

Lew and Rosaline Married in the American style

It is challenging to recreate and evaluate the fairgoer’s experience today. The AYPE was very well documented and the interiors of each venue were undoubtedly photographed in detail. This sort of record survives well for many of the expositions that preceded the AYPE - in many cases one can match items to their exact position in exposition displays – but the overall picture is difficult to obtain. For us the situation is made more difficult because this sort of image from the AYPE is not generally available to us, leaving us with strong written impressions but few details.Another problem that we have in common with all AYPE studies is that the items that were cheaply produced and distributed in the greatest quantity – often souvenir items – and other commercial advertising are what we most easily encounter today. These items are also more commonly self-documenting. The difficulty here is that a casual examination can lead to a false impression that the visitor’s experience was more formed by these most accessible glimpses into the past. Although these items are very important as well, and have a distinct story to tell, obtaining a full impression requires that we make use of examples from other sources, and not a little imagination..

Kahlili Collection Kerlee Collection

Gallery inside the Japan Building

Ah King was a great American. In 1877 he came to America at the age of 14. With his first job as a laborer in a Spokane logging camp, he realized that there were better things to do in life. He soon became an entrepreneur and a philanthropist.

In the early 1900s it was difficult for the Chinese as there were many anti-Chinese sentiments. The 1882 Exclusion Act, where no longer can Chinese come to America to take jobs away from the Americans, did not help the situation. With the approach of the 1909 AYPE, the Chinese began to prepare for it. The Chinese Government declined to fund and build a Chinese Village nor participate in the planning of the exhibits at the fair. Although Ah King was relatively new to Seattle as compared to many other successful established Chinese, he managed to successfully bid for the Chinese Village.

The AYPE Chinese Village also consisted of a Chinese Theater and Chinese Temple. He provided all the exhibits and entertainers to assure that the Chinese were represented in a true Chinese environment. He invested a total of $25,000 (in 2009 dollars this would be approximately $750,000 to $1 million) for the buildings, exhibits and transportation for the

entertainers. Other countries had their respective governments finance their countries’ exhibits, while Ah King had the courage to invest his own money into building the village. In December 1908 he went to China to arrange for exhibits and the entertainers. Before he left, he conveyed to his associates the details to be taken care of in the village. He had

great faith in his associates to assure things were done correctly, as he did not return until the day before the opening of the AYPE.

In a letter to AYPE, he agreed to pay a fixed fee of $3,000 plus 25% of the main gate receipts. In the letter he anticipated a deficiency in the receipts. As he predicted the village’s gross receipts were only $21,450 and he still had to pay $4,850 to the AYPE for their share.

Indeed he did lose money on the venture, but if there is any consolation the Chinese Village

made almost as much money as the Japanese exhibit. The Japanese Government financed the Japanese village and there were thousands of Japanese living in Seattle as compared to the hundreds of Chinese living here.

Several photos of the Chinese Village located on Pay Streak are presented. A typical advertisement poster will be shown emphasizing the positive aspects of the Chinese Village. A letter to the AYPE officials outlining his expenses and the fee to be given to the AYPE. A typical letter of introduction from a U.S. Senator is shown to assure he is given full

cooperation in China.

Howard King's family

Ah King and other Chinese civic leaders greeted a Chinese prince and two other official commissioners in Seattle, 1906.

Ah King

Banner of Seattle's Japanese, AYPE

Other symposium pages: Asian-Pacific Perspectives on the AYPE

Starting with a brief overview of the Chinese in the Pacific Northwest in the late 1800s and early 1900s, there will be a description of the events and conditions that brought the Chinese here and their treatment by the local population. The presentation will touch on the Chinese Exclusion Acts and the anti-Chinese riots. Other topics will be Goon Dip, promoter and financial backer of China Day, the parade and dragon; Lew Kay, chairman of China Day; Ah King, his trip to China and the Chinese Village; The Tin Yung Qui Troupe, the stars of the Chinese Village; how the Chinese Acrobats were held at Canadian border; the local and imported Chinese workers; Chinese dignitaries, merchants and families who attended from Canada and the Pacific Northwest.

This talk will discuss the Japan pavilions in the Alaska-Pacific Yukon Exhibition within the context of the many Japanese pavilions around the world that addressed the multiple requirements to represent a nation and address the specificities of time and place far from their point of origin.

Butterfly exhibit, Japan Building

Ad for Chinese Village

The AYPE endeavored to showcase the economic and cultural development of Washington State, including its trading relationships throughout the Pacific Rim. While there was no formal state-sponsored exhibit from China, the Chinese Village was a well-visited, impressive presence on the Pay Streak of the AYPE, sponsored and managed by local Chinese Americans. Would most AYPE attendees have arrived with a notion of Chinese culture? How would those notions have varied? In order to fully examine the perspectives of attendees, hosts, and exhibitors of the AYPE alike, we must understand the well-establish bureaucracy that existed to prevent the immigration of Chinese people to the United States. The few Chinese nationals that traveled to Seattle to perform in the AYPE would not have experienced the commonly arduous bureaucratic process faced by all other Chinese and Chinese Americans as they entered the U.S.

Qi Line Wilbur, 1910, from Chinese Exclusion Files at NARA i

Yuen Fun, 1908, from Chnese Exclusion Files at NARA

It is likely that the Chinese immigrants of the AYPE were most familiar with the rules established by the Lu Ban Jing, that being their ancestral guide for ordinary people. The carpentry manual, the Lu Ban Jing was thought by some to be observed in the architecture of China from the Song Dynasty on. It was a manual such that it gave a tendency towards explicit formulation and codification of the rituals of everyday life. So, while the buildings at the AYPE may have allowed the visitor to have an understanding of the imageries; it may not have exposed other attributes that define the complexities of Chinese culture. Moreover, these aspects that I propose to discuss are not necessarily tangible---they are timing, ritual, and preservation of harmony. These guidelines not only created the process of building but also created and became the natural way of living of the Chinese people of the time and possibly for some today.

Chinese buildings at another exposition

Plan of fairgrounds, AYPE

Ancient Chinese compass

Formosa Tea House, AYPE, 1909

Garden at Maneki Cafe, ca. 1930

4 Gentle Gardner - spirit of his homeland: pleasure & business

The Furuya Resort House was his one pleasure, a sanctuary where he was able to capture the spirit and culture of his homeland. All the plantings including bamboo, maples, paulownia trees and wisteria were shipped from Japan. The landscaping included a large pond with koi, a bamboo bridge and two large lanterns. Most Sunday’s, picnics were held by UW students and prefectual association. On the six acres of land with 300’ of shoreline, he had unlimited supply of clams and fish. Furuya’s garden featured a large display greenhouse and 8 hothouses where he grew 5000 pots of lilies, vegetables and flowers providing annual sales of $7000. The chrysanthemums grown in the fall represented a central symbol of Japanese identity.

Furuya with offficial Japanese group at Japan Building, AYPE

Furuya estate on Bainbridge Island, 1904-1933

Opera singer Aiko Sato digs clams on Furuya's beach, 1920s

Chinese acrobats

Japan Buulding, AYPE